Europe's Son

Kino in Europe

CORRESPONDING SUBJECT PAGE LINK: Click on the link below to the corresponding subject page that gives more information on Kino’s birthplace of Segno with its Kino Museum and live web camera of the Val di Non. To view the corresponding page, click Segno Birthplace page.

Kino Birthplace

Segno, Province of Trent, Italy

Kino 's Journey From Segno to Mexico City

Frank C. Lockwood

Main Article

Tyrolian Heritage and Kino's Birth 46 - 1645

Eusebio Kino, was born in the Province of Trent, Italy, at the village of Segno in the Valley of Anaunia. He was presented for baptism at the parish church of Saint Eusebius at Torra August 10, 1645; and, as it was the custom in Italian families to baptize infants immediately after birth, we may be assured that he was born on that day. Segno and Torra are a short distance apart. ...

The name Anaunia is very ancient and its history interesting. In the year 46, A. D., the Anauni were granted Roman citizenship by Emperor Claudius. The decree conferring the privilege upon them was engraved on a bronze tablet, and hung on the door of a pagan temple. After many centuries the temple was destroyed and the tablet was buried in the ruins. When work was being done in the Black Fields near Cles in 1869, the memorial was unearthed, and was found to be undamaged. I have a photograph of this relic. Anaunia was so named for the people who first inhabited this valley. In the course of nineteen centuries the name has undergone various changes and abbreviations, from the Latin and the medieval Italian forms to the present modern Italian spelling Val di Non. In 1291, the Counts of Tirolo took forcible possession of the County Sporo-Flavon in which were included the villages of Torra and Segno. Until 1803, these villages belonged to the County previously named. ....

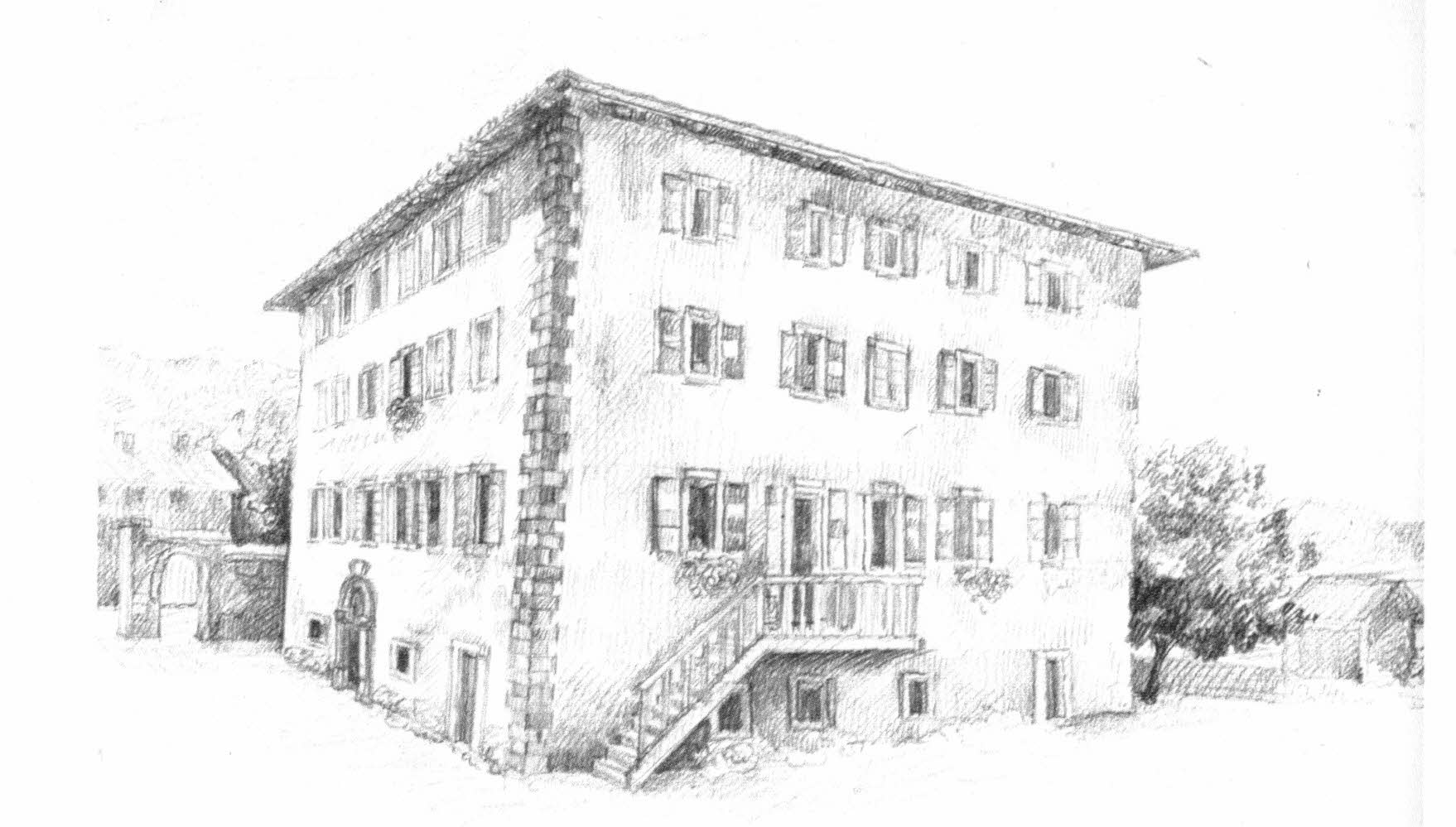

The valley of Kino's nativity was converted to Christianity in the fourth century by Saint Vigilius, Bishop of Trent, who later suffered martyrdom. The boy Eusebio came of a very ancient line, and one not undistinguished. He was a descendant, in the fourth generation, of Dr. Simone Chini, Notary and Imperial Judge, who on March 15, 1529 obtained from Charles V a grant of nobility. He was able to trace his lineage back four generations to Bartolameo, who was living in 1380. The descendants of Dr. Simone Chini, in 1600, became proprietors of the greater part of the taxes of Segno and much of the property of Mezzocorona. They had a tomb of nobility in the church of Torra. It is a circumstance of no little interest that the house in which Eusebio was born is the very one in which his ancestor Doctor Simone lived, and that it is still standing. .... The charter of privilege authorizing Simone Chini to make use of the Insignia and Ornaments pertaining to his order of nobility, issued by the Imperial Council of Charles V, is a document steeped in the spirit of the past - an echo from the borderlands of the Feudal Age. ....

There seems to be almost nothing known about Kino's parents or about his boyhood activities. Presumably, he began his serious studies in the Jesuit College at Trent - at a fairly early age, no doubt, for we know that he was a student of rhetoric at eighteen.

Munich

Home of the Elector of Bavaria

Missionary Call in Jesuit Germany 1645 - 1678

It was while here at Freiburg, on November 20, 1665, that Kino obtained entrance to the Society of Jesus. ...... How ardent his desire was to carry the light of the Gospel to the benighted natives of California and Mexico we shall read in the six letters that he wrote to the Father General between 1670 and 1678.

For the present it is best to follow the educational career of this gifted and devout young man. In 1667, he began his philosophical studies at Ingolstadt. When he was just about to complete this three-year course he writes as follows to the Father General:

_________

"Very Reverend Father in Christ

The Peace of Christ

Seven years have now passed since the time when I, a student of Rhetoric, confined as I was to my bed because of a serious wound followed the advice of one of our Fathers, to whom was known my purpose already most ardent to seek admission to the Society and to undertake the Indian mission, and made a vow that, if I should recover my health, I should seek both admission to the Society and appointment to the Indian Mission. And now, since through the matchless kindness of divine bounty I was received into the Society five years ago, and since that most earnest desire of obtaining the Indian Mission or one similar to it has not diminished in the least but rather has increased day by day to such an extent that even if I were entirely freed from the vow made seven years ago, I should still most persistently seek a Mission of that sort, I have decided, now that my study of Philosophy is almost finished, to place my prayers before Your Reverence.

And so, while I feel that by the grace of God my attitude of mind is such that, in whatever place or office even the most humble I may be placed by the direction of any superior, I shall be content with that, I am most earnestly asking, nevertheless, from Your Reverence the Indian Mission or the Chinese or some other like those and very difficult, if anything under divine favor is difficult. But He knows, He who has graciously increased my eager desire to endure and to suffer many severe toils for the greater glory of God, and the salvation of men, God, I say, knows that never will a fulfillment be granted more in accordance with my prayers than to be permitted to pour forth my blood and my life in love of Christ Jesus and for the benefit of the Church and the Society; but because now and until the kindly providence of God shall decide otherwise I deem myself altogether unworthy of a blessing so desirable and excellent, most eagerly in my ardent soul do I yearn to perform |23| the more usual duties of the Society in the midst of the varied experiences of toils, prisons, pains, poverty and scorn.

Since this would be attained most fully of all places in the Indian Missions, I again and again ask and pray Your Reverence that you do not hesitate in accordance with your watchful and more than paternal kindness toward your servants to grant these prayers of mine; and this will be the more fully shown, the more quickly these prayers of mine, that I be sent to the Indies or to another Mission of that sort, are granted. Certainly this favor once received, seeing that it is priceless, I shall never be able to forget in time or eternity, unless I am ungrateful. And so myself and my being sent I most humbly commend to the most holy Sacrifices of the Mass of Your Reverence, I write and most humbly ask that my prayers be granted, falling on my knees before the image of the most holy and indivisible Trinity, of the Blessed Virgin, and of Our Most Holy Father.

Ingolstadt, June 1, the festival of the same most Holy Three, 1670.

Of Your Most Reverend Paternity

The Most unworthy Servant

Eusebius Chinus. S. J. "

_________

Chini's request was not granted at that time. Instead, he was sent to Innsbruck to be instructor in letters at the College of Ala. But so great was his desire for missionary work on the dangerous frontiers of the world that, on January 31, 1672, from Innsbruck, he renews his most earnest prayer to the Father General.

Again his prayer was denied. So in 1673, he returned to Ingolstadt to begin his regular four-year course in Theology; not, however, without again urging that he be sent to some remote and dangerous mission field. This third letter is dated July 18, 1673, and like the previous one is written from Ala on the Inn. ....

This letter, like the others, failed to convince his superiors at Rome that the time had arrived for him to take up the missionary labors that he longed so earnestly to begin. So back to Ingolstadt he went; and it is from that city that he next writes, February 25, 1675. He is now almost thirty years of age. He has proceeded far in his studies, having completed his three years in philosophy and being now in the second year of the four-year theological course.

Among other interesting items to be found in this letter |25| is the reference to his fondness for mathematics and the facility with which he pursued the study of the mathematical sciences. More than once his future career was to be influenced in no slight degree by the fact that he was proficient in these branches. He taught mathematics while he was in the University; and, he states that in 1676 he entered into a discussion of mathematics with the Duke of Bavaria and his father when they were visiting Ingolstadt on a sort of tour of inspection. So strongly were they impressed with Kino's ability that they invited him to remain in Europe and teach his favorite sciences in the University. ...

Three more years go by, and now, having completed his course in theology, he passes on to Old Oettingen, Bavaria, for his third and final probation before the assumption of the solemn vows. It is while at Oettingen that, for the fifth time, he requests the Father General to send him as a missionary to the Indians. In this letter he reveals an excited and confident expectancy; for he has learned that missionaries for the Indians are actually being enrolled. ...

Trail in Dolomite Alps

From Bavaria Over Brenner Pass To Tyrol

Journey From Germany to Genoa Via Tyrol

Almost before the letter just quoted was out of his hands, word came to him that the Father General had at last acceded |27| to his desire. He barely took time to prepare what things were required for his long journey. For this purpose he stopped a few days at Munich. There was little to hold him in the Trentino, for he had no worldly goods to dispose of. Long ago he had said farewell to any craving for material things; and, as the last male of the family, he had conveyed his entire property to the Company of Jesus - this transaction having been completed on December 10, 1667, while he was at Ingolstadt. Of his separation from his mother country, to which he was never afterward to return, Dr. Eugenia Ricci writes very touchingly: "There remained only the patrimony of his soul - the love of his native spot carried with him in his heart."

Here is the last of his six fervid letters to the Father General.

_________

"Very Reverend Father in Christ,

The Peace of Christ.

I present to Your Reverence my heartiest thanks that you have deemed it proper to give assent so kind and so timely to my prayers for securing the Indian Mission. I shall be the most ungrateful of mortals, if, as long as I shall live, I shall not be most constantly and steadfastly mindful of the matchless favor which I have received. May I be able to act in a way befitting the special graciousness herein shown to me. May the most potent love of Christ Jesus cause that I never wish, do, speak, or think anything which shall be inconsistent with an appointment so eminent. About six weeks ago I sent a letter to Your Reverence in which I commended to you my appointment to the Indians, and scarcely had my letter left Germany, when our Reverend Provincial Father came to the House of the Third Probation at Oettingen. He told me that assent had been given to my prayers by Your Reverence.

And so having received from the same Reverend Provincial Father an official letter of appointment directing me to Genoa, Father Antonius Kersparner and I, on March 30, left Oettingen for Munich. We stayed at Munich six days until the things necessary for our journey should be prepared, and leaving there on the seventh of April we took the road into the Tyrol to Hal and Innsbruck. We arrived at Innsbruck on the twelfth of April, at Trentino on the eighteenth, at Brixia on the twenty-fourth, at Milan on the twenty-seventh, and on the second of May we reached Genoa, being, praise to God, at all times safe, at all times unharmed; especially were we everywhere most kindly received and treated by our brothers.

Of the missionaries ordered here to Genoa we arrived first of all, although two days after our arrival seven others from Bohemia also reached here, and four others are expected to arrive within two days. There is, however |28| ever at present no opportunity for going by sea to Cadiz; we hope that God will soon furnish a way; otherwise we shall undertake the journey by land or in what way shall seem best to our Superiors. And so with the repetition of my most sincere thanks, most humbly and most earnestly I again commend myself and my Mission to the most Holy Sacrifices of the Mass of Your Reverence.

Genoa, May 6, 1678.

Of Your Very Reverend Paternity

The bond-servant in Christ.

Eusebius Chinus, S. J. departing for Mexico. "

|29|

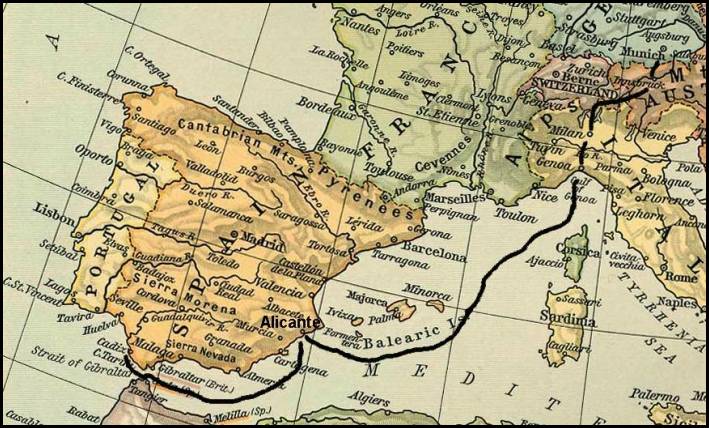

Kino's Travels To The New World

Munich to Seville

Two Year Delay in Spain & Correspondence with The Duchess 1678 - 1681

June 12, 1678, in company with eighteen other Jesuit missionaries, Kino took ship at Genoa, expecting to embark at Cadiz for the New World. The passage to Cadiz was slow, as the Fathers encountered dangerous seas in the early part of the voyage and were later becalmed for several days. At the end of two weeks they put in at Alicante on the southeastern coast of Spain. A good many vessels were seen between Genoa and Cadiz, and so warlike were the times that the sailors constantly held themselves in readiness for action. They were unmolested, however, and at last reached Cadiz - though too late to catch the Royal Fleet for the West Indies. At Seville they were taken ashore, and here they had to wait many months. But the time was not spent fruitlessly, for the younger priests continued their studies and the older ones devoted themselves to the mastery of the Spanish language, to the study of mathematics and astronomy, and the manipulation of various instruments of navigation, such as the compass and the sun-clock.

In the early spring of 1680, the Fathers went to Cadiz hoping for an early embarkment; but it was not until July 10 that they were able to take ship. At that time, the Fleet for the Indies being in readiness for the voyage, the missionaries were taken aboard "The Nazarene."

We are able at this point to pick up the thread of Kino's fortunes through a wonderfully interesting series of letters written by him between August 18, 1680, and February 15, 1687, to the rich, devout, and renowned lady, the Duchess d'Aveiro, de Arcos, y de Maqueda. She was one whose whole heart and soul was bound up in missionary work among heathen people in all the remote parts of the earth. The Fathers called her "Mother of Missions," and priests all over the world corresponded freely with her concerning their labors and the progress of the numerous missions which she fostered. ...

Kino wrote the first of his many letters to the Duchess d'Aveiro August 18, 1680. In it he tells her that after living two years in Seville waiting for passage to their field in the New World, he and his companions embarked July 10, on "The Nazarene," one of the vessels of the Royal Fleet bound for the Indies. He explains that immediately after setting sail "The Nazarene" came to grief among the rocks and almost foundered. He goes on to say that after awhile:

"The sea became calm and we returned safe and sound to the city and our college towards the evening. Our Proctor |33 | of the Indies proceeded to ask throughout that night what hope we had of returning on board; whereupon, when he learned that the vessel would not be seaworthy for some weeks, he returned to the college; and at two o'clock that night he roused us to go and embark on the other vessels of the Fleet, which we reached at about seven of the following morning. We were nearly all without cloaks, caps, or breviaries as we had been on leaving the shipwrecked vessel "Nazarene"; but in spite of many prayers and supplications, they would not receive on board any of the vessels more than eleven missionaries; the others, amongst whom were the writer and three novices, were obliged to return to Cadiz and to the College."

At first it was hoped that "The Nazarene" could be repaired in time to continue with the Fleet. But this expectation proving vain Kino, with Father Thomas Revell, was left in Cadiz to do the work of the College there, while the Proctor and the other missionaries who had been left behind went to Seville. ...

In a second letter to the Duchess, written September 15, 1680, while he is still waiting at Cadiz, uncertain what the decision of the Father General might have been with respect to him ... He tells her Grace that there is still some expectation that he may be able to set out for New Spain before the end of the year, either in ships from Honduras that are expected to arrive soon, or in a dispatch boat bound directly for Vera Cruz, or in ships destined for the Leeward Islands that she had told him about.

Before the letter is posted, he adds this fresh bit of news from the wide seas:

"During the last four days the ships have arrived from Honduras, and they bring bad news - that the French and English and other pirates have sacked Porto Bello, and that they wish to proceed to Lima. They also report that between Panama and Cartagena some rich gold mines have been discovered; and within the last three days three ships have put in from Biscay, which, they say, are ships from the Indies or windward squadron."

In a letter to the Duchess dated November 16, 1680, Kino reverts to her passionate interest in the mission to the Mariana Islands and the quest for the "Unknown Land of Australia"; and, after mentioning that Father Theofilo and other missionaries are now on their way there, adds: "If we cannot follow these lucky Fathers on their journey to the Eastern Church with our bodies, we can at least follow them mentally and pray for them and their success continuously, as well as for their successors in the whole of the Orient and in the "Unknown Lands of Australia."

He continues:

"God knows how eagerly some ten years ago I endeavored to obtain at Rome and elsewhere a Portuguese grammar so that I might learn Portuguese, or at least its chief elements while I was still in Germany, in order that |35| I might, in due course if it pleased God and my Superiors, go to the East Indies. In the letter which I received four days ago from Rome, the Father General confirms, as does also the Assistant Father of the German Province, Charles de Noyelle, that we were to go either to Paraguay, or to the New Kingdom. But since the chance is gone of going to Paraguay, we may be going to the New Kingdom as there is a despatch boat which will leave Europe with the Fleet, and will take us to the Port of Vera Cruz, as the Father Procurator of the Indies has warned us, who wishes that those Fathers who are destined for the Philippines, or the Mariana should follow the others who are going to Mexico with the Fleet, so that they may be able to take a boat in Acapulco for the Philippines."

In this same letter Kino, in reply to inquiries made by the Duchess as to his nativity, has this to say: "What your Grace wishes to know about me I will write most willingly about my nation and my country; I am a Tyrolese from Trento, but I don't know whether I can say whether I can call myself an Italian or a German, because the town of Trento makes use of the Italian language, laws and habits, but although it is situated in the very extremity of the Tyrol, and although our College of Trento is the college of Upper Germany, it is usual to speak Italian there." ...

It is now mid-December, 1680, and Kino still at Cadiz, is in constant readiness to set sail for his unknown field in the far seas.

He writes:

"I have received your letters with those enclosed intended for Mexico, and I shall do my utmost that they shall reach their addresses safely.

"As regards my mission, I desire my eternal salvation, but value equally and desire even more the conversion and salvation of the heathen Indians. But, with the help of God, I shall always be obedient to God's will and my Superiors.

"Your Grace's prayers will procure for me that great joy and reward, however, and whenever it appears good to God to send me I shall go. If I consider Japan, and the victories of its martyrs which have been obtained by the love of God, then your letters which I have recently received, and which mention Japan, seem to me most pleasing. If, however, I look at China with my mind's eye I am delighted that I spent so many years in the study of mathematics and other sciences, which were so pleasing to me that it has always been a delight to me to live in rooms in the colleges which had windows to the East so that the aspect of the East, where I always intended to go to convert to God, delighted me."

In a letter to the Duchess d'Aveiro written from Cadiz on December 28, 1680, Kino makes mention of the famous comet of 1680-1681, which he had been carefully observing for some days. ...

He promises that in his next letter he will tell more about the comet - its size, its distance from the earth, "Its exact locality, and its unhappy effects upon the Kingdoms of Europe." So, on January 11, 1681, after some comment upon the possibility that some missionaries who had already been designated for the New Kingdom would have to remain in Spain owing to lack of funds for the journey, and

A reference to the rumor that the Fleet was to sail within a few weeks, he goes on to say:

"With regard to the great Comet which is visible here (and as I believe throughout the world) we saw it in the evening at the hours of 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, and later, and you will have understood from my (previous) letter that this Comet has been observed by me almost every day in the sky, except the last three days when the obscurity of the sky prevented us from observing the Comet. Notwithstanding, I think, that, even in these last three days, the Comet ascended by its own motion towards the Arctic Pole in a slight declination towards the East, and that it will pass the Tropic of Cancer. And although the longitude of the Comet's tail from the 5th of January when it almost reached as far as the seventieth degree has been diminishing daily, I firmly believe that the Comet will last the whole month of January, and a considerable part of next month."

Finally the time is at hand when Kino is to set sail for Mexico. He conveys this news to the Duchess in a letter of January 26. For eight days the galleons had seemed to be on the point of departure. The Viceroy and the Vicereine had even gone on board their ship, and the missionaries, three days before, had sent all their bags and boxes aboard. But, writes Kino, there is still a possibility that their departure may be delayed three more days on account of the strong wind which has prevailed. The missionaries bound for Mexico most eagerly await the Father Procurator, cheered by the report that he has already reached Seville on his journey from Madrid. So Kino closes his letter with the words: "The end of my letter is this, to say good-bye in Europe." |38|

A month later, aboard ship near the Canary Islands, he writes again, giving some details of the voyage up to that point. The passage consumed three months - to be exact, ninety-five days if we count both the day of departure from Cadiz, January 29, and the day of arrival in Vera Cruz, May 3.

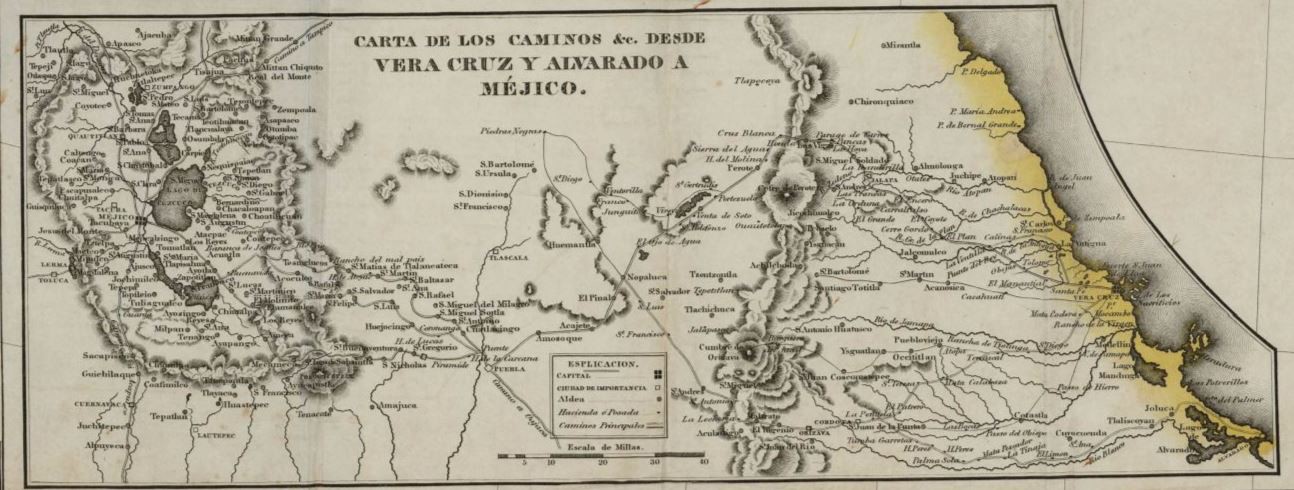

Mexico City Arrival and Destiny in the Missions 1681

Upon reaching Mexico, Kino at once sent a full account of his long voyage to the Duchess d'Aveiro. ....

As to his own probable destination he has this to say:

"Father Baltasar is trying to send me to China, and several days ago he mentioned the matter to the Father Provincial of the Province of Mexico, endeavoring to obtain me for the Far East. But the Father Provincial has not given Father Baltasar his definite consent, on the contrary, he intends to send me with another veteran missionary father to California whither in a few months ships and soldiers and a magnificent expedition are being sent to discover whether this be indeed an island or a large, vast peninsula. It may, however, be that the Father Provincial will yet give his consent ..... In the meantime, however, I do not listen to one more than the other, nor do I let myself wish one thing more than the other. On the 23rd of June at 6 o'clock in the evening, we had a great earthquake here. Many public prayers had taken place, in order to obtain rain. I suspect that this extraordinary drought had somewhat caused the earthquake, because afterwards there was a great inundation." ...

Frank C. Lockwood

"With Padre Kino On The Trail" 1934

Excerpts from

Chapter II. Ancestry, Education, And Missionary Call

Chapter III. From Genoa To The City Of Mexico

To download the entire chapter II and III, click

Kino in Europe - Lockwood document (text)

To download Lockwood's entire book "With Padre Kino On The Trail", click →

http://uair.library.arizona.edu/system/files/usain/download/azu_h9791k55z_l81_w.pdf

Birthplace of Eusebio Fransciso Kino

Val di Non in the Province of Trent, Italy

"Valley of Canyons"

Lake Santa Giustina Dam Built in 1950

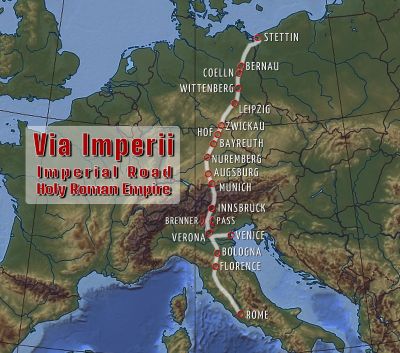

Kino's European Travels (1645-1681)

Edward J. Burrus

Summary Article

|16|

Eusebio Francisco Kino was born on August 10, 1645, in Segno, near Trent, Italy. [1] After elementary schooling at home and in the village school, he continued his studies in Trent from about 1656 to 1662. [2] Inasmuch as Segno is some twenty-one miles directly north of Trent, it is obvious |17| that little Eusebio had to live at the Jesuit school during the school year, and could come home only for the longer vacations such as Christmas, Easter, and the summer.

In the autumn of 1662, he undertook the first recorded long trip of his life. [3] He had shown exceptional ability in his studies at the school in Trent and was offered a scholarship at the Jesuit College in Hall, Austria, a town situated a few miles east of Innsbruck. The large Tyrolese city lies about eighty miles directly north of Segno. We are not told how Kino reached it. He could have either ridden on horseback or taken the post diligence which linked Trent with Innsbruck via Bozen; even today, the traveler follows the old Roman highway that threads the Brenner Pass. [4]

Hall was to be his home for the next three years (1662-1665). [5] "Falling desperately ill here, he promised that, if he should recover, he would enter the Society of Jesus and volunteer for the foreign missions. He added Francis to his name in gratitude for the recovery which he attributed to Francis Xavier, Apostle of the Orient". [6] Most likely he returned to Segno only once a year during summer vacations.

In 1665, he was accepted in Freiburg, Germany, by Father Servilianus Veihelin for the Jesuit Order, and began his training at Landsberg, Bavaria, on November 20, 1665. [7] After the usual two years of formation as a Jesuit novice, he went to study philosophy in Ingolstadt. [8] In 1670, he left |18| Bavaria and crossed the high Alps into northern Tyrol; he had returned to teach literature for the next three years at his Alma Mater in Hall, Austria. [9]

He went back to Ingolstadt in 1673 for four years of theology. [10] Young Kino had shown such exceptional talent in his studies that two radical changes were allowed in his favor. He was assigned to teach mathematics and various branches of the natural sciences to his fellows Jesuits at the University of Ingolstadt; and, before completing the full theological course lasting four years, he was sent to the University of Freiburg in order to take up more advanced studies in his special fields. [11] Even with ordination to the priesthood in Eichstatt, Bavaria, on June 12, 1677, his long course of training had not yet ended; in Oettingen, Bavaria, a final year of formation awaited the young priest so impatient to be on his way to distant missions. [12]

The 1678 Bavarian Province catalogue records in a most matter of fact way a prospective adventure which must have caused two hearts to beat faster and two imaginations to conjure up dreams of boundless conquests: "April, 1678. The following two men are on their way to other Jesuit Provinces - Father Anton Kerschpamer has been assigned to the Philippines; and Father Eusebius Chinus, to Mexico". [13] The two missionaries left Oettingen on March 30, 1678. They again crossed the Alps at Innsbruck, visited Hall for, the last time, followed the Sill River to the Brenner Pass, and traveled southward over the old Roman road along the Etsch to Bozen in Tyrol. They then crossed over to Salorno, where Kerschpamer was to enjoy a final visit with his family; Kino continued to nearby Segno. [14]

They could not tarry long in their native towns because they had to reach the harbor of Genoa by May 2, 1678, |19| although it was not until June 12 that the nineteen Jesuit missionaries actually set sail. [15]

Thirteen long days in crossing the Mediterranean to Alicante, Spain, initiated the fledgling sailors in the hardships and perils of sea travel. From June 25 to July 3, the missionaries visited the harbor city and its wonders, and practiced their many and strange varieties of Latin and Spanish on their fellow Jesuits and townspeople. [16]

Bad weather and poor seamanship conspired to delay their ship from reaching Cadiz in time to board the fleet for the Indies. On July 14, as they neared the Spanish harbor, they saw before them the flotilla as it slipped over the horizon with the setting sun. [17]

First Cadiz for a few days, then Seville for nearly two years, and then Cadiz again - this time for some ten months - were to be Kino's home in Spain. The long wait was not lost in useless fretting: he perfected his knowledge of Spanish, he read more widely in mathematics and science, and made many instruments he would need in the mission field, especially compasses and sundials. [18]

On July 11, 1680, almost two years to the day after his arrival in Spain, he set sail from Cadiz on the Nazareno. Before the ship could clear the harbor, it ran into a sand bar. Rescue came soon, but passage on another ship to the Indies would make Kino wait more than six months. [19]

It was during this period of forced waiting that Kino began his correspondence with the Duchess of Aveiro in the hope of getting early passage and of being reassigned to the Far |20| East, the goal of his boyhood dreams. [20] His scientific interests received new impetus from the appearance of an extraordinary comet, which he first sighted and studied in November of 1680. [21]

Finally, on January 27, 1681, the stranded Jesuit contingent set sail from Cadiz in a special dispatch boat. [22] Despite the terrible risk of sailing without the protection of a convoy, all the missionaries felt fortunate at not having to wait at least a year and a half longer before they could board the next regular fleet for the New World.

Their voyage from Cadiz, Spain, to Vera Cruz, Mexico, took them through the Canary Islands. On May 1, they put into the Mexican harbor - a trip of over ninety days. [23]

After a short rest in Vera Cruz to recuperate from the voyage, Kino was once more on his way. He realized that he was now truly in a " new world ", amazed at the wonders which awaited him along the route Cortes had taken 162 years earlier. He visited en route Puebla with its numerous Jesuit schools, its splendid cathedral, and fine churches. A short trip brought him to famed and tragic Cholula. Then came unforgettable Huejotzingo with its superb Franciscan monastery and church. The route now climbed dizzily as he neared the high passes leading into the valley of Mexico and the capital of New Spain. He reached Mexico City about June 1, 1681, more than three years after leaving Oettingen, Bavaria, and even his native Segno. [24]

|21|

Kino was slow to abandon a cherished ideal; but when he was forced to do so, he could always adapt himself to circumstances, and seemingly could create an even higher ideal than that which he was compelled to sacrifice. The latter would be his new vision. As the reader will often have the occasion to observe, each successive vision embraced the earlier ones. Hence, his life was one of amazing growth, not a series of sterile disappointments at lost opportunities. As a young man he had for several years set his heart on working in China ; it was for this vast empire that he studied mathematics and the natural sciences. While in Spain, he resorted to every means to get to the Orient. He continued to do so in Mexico City. But on being appointed by the Mexican Provincial to the Lower California enterprise, Kino devoted himself to his new ideal with an energy and enthusiasm worthy of a lifetime aspiration. We shall see that he can again adjust himself to changed circumstances when the attempts at the conquest of California are so unreasonably abandoned.

The Conde de Paredes, Viceroy of Mexico, designated Kino royal cosmographer to Admiral Atondo's expedition to Lower California. Father Bernardo Pardo, Jesuit Provincial Superior, appointed him and Father Goñi chaplains of the fleet and missionaries to the natives of the lands to be discovered and explored. [1]

Kino and Manje:

Explorers of Sonora and Arizona, 1971

Edward J. Burrus

First Part: The Trips And Expeditions

Chapter 1 Kino's European Travels (1645-1681)

Excerpt from Chapter 2: On To California (1681-1686)

To download above chapters with footnote text

Click

Kino in Europe - Burrus document (text)

Via Imperii - Europe's Major North South Trade Route

Via Imperii

Editor Note: Kino lived most of his life in Europe along the Via Imperii, the imajor trade and communications route beginning in ancient times from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Mediterranean Sea in the south via the Brenner Pass. Today the route is the fastest and most used road and rail connection between Germany and Italy.

During Kino's time the Via Imperii was imperial road of the Holy Roman Empire .Kino lived on the route in Mezzacorona as a teenager and attended school in Trent and in Hall near Innsbruck. While training as a Jesuit he attended university in Inglostadt, taught school in Hall. Kino traveled the Via Imperii for the last time when he made his way to Genoa where he sailed for the New World.

Kino's Jesuit Formation Stages

Kino as a Jesuit scholastic (Jesuit priest candidate) completed a series of formation stages that spanned more than a decade before he was ordained as a priest. These stages also give an account of Kino’s first half of his life as a student and professor while being at the best universities in Central Europe.

Novitiate

Landsberg University 1665 - 1667

After attending Hall as scholarship pre-college student and later as a college student at Freiburg, Kino is accepted into the 2 year novitiate and lives in community with Jesuits while ministering to poor. He takes first vows of poverty, chastity and obedience

First Studies

Ingolstadt University 1667 – 1670

Completes 3 year study in philosophy and theology (Bachelor degree) while following Jesuit rules and methods. Continues to minister to the poor. Kino also studies mathematics, astronomy, cartography and other sciences with Ingolstadt's renowned faculty.

Regency

Hall College 1670 - 1673

Fully involved in the life of Jesuit community, Kino returns to Hall where he was a student 6 years before and teaches literature. He writes first letters to Superior General requesting to be missionary to China. Kino is inspired by famous Jesuit missionary to China, his deceased cousin Martin Martini

Theological Studies

Ingolstadt University 1674 - 1677

Completes 3 year study in theology (Masters degree) while continuing scientific studies and teaching mathematics. He turns down post as science professor. Kino ordained as priest in June 1677.

Tertianship

Freiburg / Oettingen 1677 - 1678

Receives equivalent of PhD in astronomy and natural sciences from Freiburg University and then Kino ministers full time in parish in Oettingen. Last of his six requests to be missionary is granted

Final Vow

Baja California 1684

While waiting 2 years for a ship to Mexico, he ministers & teaches in Spain. At age 39 in Baja California on the August 15, 1684 on the Feast Day of the Assumption of Mary, he makes before a fellow Jesuit missionary his final Jesuit vow of obedience to the Pope's order to serve in the miissions. Kino re-affirms his first 3 vows (poverty, chastity & obedience) that he made in Germany when he entered the Jesuit order at age 18 and when he was ordained a priest at age 32.

Kino's Central Europe Map

Kino In Hasburg Europe

Today's Italy, Austria, Germany and Spain

Charles W. Polzer

Place of Kino's Birth

The Early Years In Europe 1645 - 1664

The saga of Padre Kino begins in Segno, a tiny mountain town in the Italian Tyrol, not far from historic Trent. There on August 10, 1645, Eusebio was born in a typical stone and timber house similar to those that stud the slopes of the Dolomite Alps along the Val di Non. He was the only son of Franceso Chini and Margherita Lucchi and the brother of three sisters, Margherita, Catarina, and Ana María. His boyhood in Segno shaped the powerful frame that would one day explore the mountains and deserts of a land a hemisphere away. He learned the essentials of life on the family farm at Moncou which was later sold after his father’s death in 1660; the sale included the home, buildings, vineyards, and livestock. So Eusebio was not unfamiliar with agriculture from the earliest days of his childhood.

Young Eusebio must have shown some degree of brilliance because his parents provided him with a private tutor, Giorgio Coradinus Mollari, and then sent him off to the newly founded Jesuit "gymnasio" at Trent where he was introduced to the world of science and letters. Three years after his father’s death, the family holdings at Moncou were sold to liquidate some debts and finance Eusebio’s education at the college of Hall near Innsbruck in Austria. He registered in the program of rhetoric and logic, moving on to Freiburg in 1664. While studying at Hall, Kino contracted an unidentified illness that brought him close to death. These were obviously very emotional times for the young man from Segno who found his future confronted by serious choices. Was he destined to return to the Val di Non? His father had died when Eusebio was only fifteen; and the properties were sold to pay for his education. Or was he meant to be a missionary? Always in the back of Eusebio’s mind lingered the memory of the visit of his cousin, Father Martino Martini, an accomplished China missionary; his brief visit had sparked an abiding interest in science and mathematics, almost prerequisites to be a missionary to the mysterious Orient. The sickness drew from Kino one of his deep-down dreams – for he vowed that if his patron, St. Francis Xavier, would intercede for his recovery, he would enter the Society of Jesus. His health returned and for the rest of his life Eusebio Kino valued his healing as a gift from God through the intercession of Xavier. Whatever may be said of Kino’s recovery, his life was certainly to be a welcome gift for the “abandoned souls” of Baja California and the Pimería Alta.

Hall in Tyrol, Austria

Student and Later Grammar & Rhetoric Teacher During Kino's Jesuit Novitiate

Kino Enters the Society of Jesus 1667 - 1677

Now twenty years old, Kino set foot on the long trail of Jesuit training typical of the men of the “Company of Jesus.” Entering the novitiate at Landsberg, he pronounced his first vows in 1667 when he renounced any inheritance from his family. Kino now entered on the Society’s intensive course of studies at Ingolstadt, beginning with philosophy which he finished at the newly opened University of Innsbruck. Minor orders were conferred in April, 1669, and he was now ready for his first apostolic assignment, teaching basic grammar at Hall.

Five years had passed since his entry into the Society, but he had not forgotten his promise to volunteer for the missions; he filed his first formal petition to go to the Americas, to China, or any other difficult foreign assignment. Father General Oliva honored the offer with silence. Two of his Swiss professors, Amhryn in philosophy and Aigenler in mathematics, were named for the China missions, and this prompted Kino to appeal a second time for a similar assignment in 1672; he was being patient but insistent. After three years of “regency,” the period Jesuits spend prior to theological studies, Kino again renewed his appeal to be sent to the missions. The only response from the General was a recognition of his constancy in discerning his vocation. Two more years elapsed while Kino devoted himself intensely to the study of theology and mathematics; again, he petitioned Rome. Ordination was not far off, and where would he be destined afterwards? Yet another appeal rumbled down to Father General only a year later. Eusebio was showing strong determination. He was ordained a priest in the Society on June 12, 1677, at Eistady, Austria, with the other members of his class. But still, no word from Rome.

The Ingolstadt years were intense ones. Not only had Kino dedicated himself to the demands of theological studies, he delved into mathematics, geography, and cartography under a faculty of distinguished professors. The Jesuits were not isolated from other students at the relatively young university, and Kino moderated a mathematics club that concentrated in the emerging field of astronomy. In fact, he converted one of the classic towers of the university building into a mini-observatory! Although the facts are scanty, one can feel the energy and enthusiasm of this determined young man from the Tyrol; the whole world and the heavens were fair game for all his talents.

The Duke of Bavaria, whose son Kino was teaching, was so impressed with his accomplishments, he invited the young priest to stay on to teach science and mathematics. Kino, as appreciative as he must have been, however, continued to press Rome for an assignment to the missions. Finishing the “tertianship,” at Oettingen (or final probationary period in the Society’s long training), he knew men were being chosen for the Americas. For the sixth time, he offered himself if Father General felt that this was truly God’s will for him in life and in the Society.

America Or The Orient? 1678

In late March, 1678, Kino’s provincial superior arrived at the tertianship with the General’s decision; he was to be assigned to the missions of the Spanish empire! Would that mean the Americas or the Orient? Neither of the two classmates now destined for the missions lost any time. On March 30, Kino and Anthony Kerschpamer left for Munich to spend a week in making preparations for the long journey. Always resourceful, special permission was granted Kino to offset travel expenses with money he had earned from the sale of scientific instruments he had been making.

Winter was wearing away as Kino and Kerschpamer rode off to Hall where the dreams of distant worlds once dominated their lives. This time, however, the dreams had become awesome realities as they bade farewell to old companions and loyal students. Threading the Brenner Pass, the two America-bound Jesuits rode through Trentino valleys and Tyrolean hills seeking family, friends, and old professors. Spring was in the air. The sun of the southern Alpine slopes beckoned new leaves and melted the edges of snow banks into rivulets of crystal water. There was life and freshness everywhere. There was hope and adventure in his voice as Kino said goodbye to childhood haunts. The Val di Non, Mezzacorona, Moncou; his sisters, uncles, and scores of relatives in the Alto Adige were swallowed up in a wake of twisting canyons and sprawling vineyards. The Tyrol now would be only a cherished memory.

Nineteen Jesuit companions converged on Genoa to begin their missionary careers. Germans, Austrians, Bohemians, Italians, and Tyrolese made up the contingent that would eventually disperse across America, the Pacific, and Asia. Who could really describe their sentiments as they set sail for Cádiz. Excitement, a raging summer thunder storm, and choppy seas worked their unwelcome magic on Kino’s first time aboard an ocean-going vessel; but he was fine after a day. The Capitana and the San Nicolás under command of Francesco Colón of Genoa, tacked on toward the Spanish peninsula. Eight days out of Genoa, as Minorca slid past the horizon, huge sails were bearing down on the course of the two Italian ships. General quarters were sounded to prepare the one armed ship to give battle to Turkish pirates. But as the men-of-war approached, a saludatory salvo rang out; they were, for now, a friendly English squadron! The breast-works made from mattresses and boxes were stored again and the ships steered for Alicante. Nonetheless, sails continued to jab up from the horizon and battle stations were resumed off and on for the next five days until more English ships brought news that the Turks had been driven to Argel.

What a curious way the missioners must have thought to begin a life of service to the non-believer! Landing at Alicante, the Jesuits were hosted by the college because there was some thought of continuing the journey overland. Word arrived, however, that the armada was delayed at Cádiz and would not embark until around the 12th of July. The decision was taken to continue on by sea. From the 26th of June to the 14th of July the small squadron plied the stormy waters of the western Mediterranean. Phantom ships loomed up from the African coast; dense fogs confused the pilots who promptly steered the crafts into Ceuta instead of Cádiz. Then, at the crack of dawn huge sails bore down on them from the east; rushing to battle stations, again, the small Italian vessels slowly tacked away until the threatening ship vanished from sight.

By noon of the 14th they sighted the Straits of Gibraltar, falling on their knees in gratitude for having reached the classic portal to the Atlantic. The ships triumphantly scudded along the desolate coast of Trafalgar. Hope was high until sunset. Then, the brilliant sun outlined the imperial Spanish armada, standing out to sea en route to America. Kino’s heart, everyone’s heart sank with that setting sun. Contrary winds were keeping them from their rendezvous. Beautiful and dramatic, the sight of forty-four galleons just miles away dashed the expectations of everyone aboard! Winds, tempestuous seas, pirates and fog had interrupted their fateful journey.

Seville in the 17th Century

"Quien no ha visto Sevilla, no ha visto maravilla."

The Wait In Spain 1678 - 1681

Missing the fleet was not quite like missing a scheduled transatlantic steamer. As Padre Kino and companions feared, they would have to wait nearly two years to book new passage! Few other places in 17th century Europe could offer the advantages of Andalusia which was the virtual throat of western expansion. Ships and passengers from all over the world converged on Cádiz and Sevilla with news and cargoes. So, Kino’s keen interest in the Orient was honed even more sharply with news of Macao and the Marianas, and a newly struck friendship with Father Teófilo de Angelis, the appointed superior of the Pacific missions, enkindled in Eusebio a desire to join in the expedition to the Carolines. It never happened because De Angelis embarked before a change of assignment could be received from Rome. But the interlude occasioned Kino’s acquaintance by correspondence with the Duchess of Aveiro, a staunch patron of Jesuit mission activity in the Orient. Not even her powerful intercession, however, was able to divert Kino from his destiny with New Spain. While he waited for word from Rome or for permission to board an America bound armada, he spent his time mastering Spanish, some Portuguese, teaching mathematics at the Jesuit colleges in Seville and Puerto Santa María, and making scientific instruments for use in the missions.

Just over a year had elapsed when the Jesuits got their chance to sail; but learning that the destination of the small fleet was first the coast of Angola to take on slaves for the Americas. The Jesuits refused to be associated with the business. More time passed in Sevilla until the Father Procurator booked passage for them on the flota which would accompany the new Viceroy to New Spain. Rushing to board the Nazareno in the port of Cádiz, the expectant missionaries were thrilled to be under sail – but a large ship threatened to collide with the galleon that slammed into a shallow sandbar, still known today as El Diamante. Winds and waves crashed over the stricken ship, and the passengers barely escaped with their lives. Viceroy Paredes’ fleet left port with a few lucky missionaries destined for the Orient and south America. Kino recovered some of his baggage and once again sailed upriver to Sevilla for another winter of waiting.

Finally, letters arrived from Rome in mid-November that tried to calm Kino’s anxieties. If the opportunity arose, he could, indeed, join his German province companions to go to Nueva Granada (Colombia) or even the reducciones of Paraguay. It seemed to Kino that his life’s destiny was still unclear. Just what was the will of God saying? Since leaving the mountain fastness of Austria, Kino had lost out on his preference for the Orient. His companion through years of preparation, Anthony Kerschpamer, had won the draw of destinations; Kino’s slip of paper read “Mexico”; Kerschpamer’s, “Oriente.” Like a gamy trout, he had tried to escape the hook of destiny. And now in the chill of the Andalusian winter, he hoped for other climes.

Crisp and dry, the skies of southern Spain were ideal for astronomical observations. As Kino’s third winter in Sevilla debuted, a brilliant comet stretched across the Andalusian skies. Using instruments of their own manufacture, the Jesuits speculated on the nature and meaning of the heavenly spectacle. For Kino it was a unique event that offered an explanation for the raging pestilence in the city. He had hardly concluded his observations when word came for the lingering Jesuits to leave for Cádiz because an armada was forming to bring the Viceroy of Peru to his post. Kino would be aboard a smaller packet or mail ship that would break off at Havana for the port of Veracruz, where he arrived May 1st or 2nd after ninety-six days at sea. America at last!

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

"Kino: A Legacy: His Life, His Work, His Missions, His Monuments" 1998

To download above chapters, click

Kino in Europe - Polzer document (text)

The Wreck

Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky

Kino Diary - Genoa To Seville

Herbert E. Bolton

For the journey of Kino and his companions from Genoa to Spain we have the excellent diary kept by Kino himself. [1] It is written in |40| Latin and addressed to the father provincial. We also have a good account of the sea voyage by Adam Gerstl, one of Kino's traveling companions. Their experiences were typical of Jesuit travel to America. Nineteen Black Robes left Genoa on June 12. Gerstl gives us the names of eighteen. [2] It was the plan that all should go to Spain and thence to Mexico. There seven would remain; the other twelve would go on mule-back to Acapulco and sail thence across the broad Pacific to the Philippines. It was no soft journey which these voluntary exiles were facing.

Before noon of the fateful sailing day the nineteen travelers, accompanied by many Genoese priests, went from the Casa Profesa down to the harbor. From the shore they were rowed four German miles [3] out to the flagship, a goodly craft commanded by Captain Francesco Columbus, said by Kino to be a relative of the great discoverer. On this vessel, counting crew, soldiers, and passengers, there were two hundred persons besides the Jesuit band. A smaller vessel, the "San Nicolás," was there ready to sail in company. ...

The landlubbers soon got a typical initiation into sea travel. On the day after starting there was a violent wind, followed by thunder, lightning, rain, and a heavy sea. Kino proved to be a good sailor. He was not altogether exempt from "mal de mar," but he quickly recovered. ...

There were other diversions than storms and seasickness. Fear of pirates kept everybody free from excessive ennui. It need not surprise one that there should be soldiers on this merchant vessel on which Kino was sailing, for the Mediterranean was still infested by Algerine pirates, then commonly called Turks. ... And every seaman, soldier, and passenger regarded a voyage on the Mediterranean as a chance for adventure. It is not strange that every sail was feared as a pirate ship.[3]

They were nearly a week out of harbor when the first scare occurred. On the morning of June 18, when in view of the Island of Minorca, from the lookout they caught sight of two large ships approaching from the south. Taking them to be Turkish freebooters, the captain ordered everything in the flagship made ready for a fight. The missionaries contributed their share. "In accordance with a custom observed at sea, we handed over the coverings and mattresses of our beds, in order that the soldiers and sailors might so suspend and dispose them as to form a breastwork." Thus sheltered, the soldiers were ready to fight. The Jesuits now withdrew to a place of safety. "We gathered up our other personal belongings as well as we were able, and most of us betook ourselves to the Captain's quarters, in order that the officers and men might have a freer field for discharging the guns and performing the other maneuvers of war."

For a long time everybody was in suspense. It was not plain whether the pirate ships were approaching or receding. But nothing happened. Dinner was served. Suddenly, at the end of the meal, the men were all ordered again to their posts, for the strange vessels were close at hand. But soon there was a sigh of relief, for it was now seen that the ships bore the flag of England. They were friendly craft; Captain Francesco saluted them with seven guns, and the Jack Tars returned the compliment with five. ....

On the voyage the Jesuits did not slacken their accustomed religious routine. Mass was said every morning by several fathers, sometimes as many as seven, unless the sea was rough and stomachs were squeamish. There were sermons, confessions, and communion. ...

Sailor's oaths on this voyage were milder than usual. The fathers were bound for missions to the heathen. But on board they did not miss their splendid opportunity to hold a mission "entre fieles." Among a hundred or more sailors and soldiers there were hardened fellows who had not gone to confession for months or even years. The zealous young evangelists rose to the occasion, and through their influence some of the crew were smitten with contrition. Kino writes on June 15, "Among the sailors there was one who after darkness had fallen sought me out to atone for his sins by the sacrament of confession." One night after supper Father Calvanese preached a powerful sermon from the prow of the ship. He must have been eloquent, for next day the harvest was bounteous. Seventy took communion that day. [5]

Kino was born with the instincts of a traveler, and he took an interest in all he saw. His diary was kept like a veteran's. He described seasickness, ship routine, meals, storms, strange vessels. One day he amused himself watching dolphins, and there was a whale "which |44| exceeded in size even the larger ships which came to Ingolstadt on the Danube and to Hala on the Oenus for wine." Speed varied according to wind and weather. The first morning after starting, the Capitana was scarcely more than a mile from its anchorage at Genoa. On June 14 they saw at their left the island of Corsica. Next day and the next they were becalmed for hours. On the 18th they caught a glimpse of Minorca, which they kept at their right. Two days later they reached Formentor, asylum of a Spanish penal colony. ...

On the morning of June 25 the vessels arrived at the harbor of Alicante, or Alona, as it was often called. There, in plain sight when Kino awoke, were the light house, the high perched castle, and the flat roofed city itself. The landing was made with due ceremony. Captain Francesco sent an officer ashore in a boat with health certificates and other papers necessary for entry. Salutes were fired and anchors cast. When the launch returned from the town it brought two fathers from the Jesuit College of Alicante, who had come to welcome the visitors. Before night all the missionaries went ashore, taking most of their baggage, for there was talk of continuing the journey to Cádiz overland. They reached tierra firme about seven o'clock, and were conducted to the College. ...

Besides several regular feast days which fell during the visit, there were special occasions which offered novelty. On the very night of their arrival, without awaiting supper, the visitors all went out on the street to see a procession organized to counteract the plague, which was prevalent in neighboring towns, and to avert threatened war. With the brilliantly lighted torches, and the procession of monks carrying the sacred Veil of Santa Veronica, the spectacle was impressive. One day Kino said Mass in the church where the Sudarium was preserved. In the afternoon all the visiting Jesuits, accompanied by the Rector of the College, went to the same church to kiss the sacred relic. These were memorable experiences for the devout traveler. ...

On July 2 the Captain notified the Jesuits to be ready to go aboard next morning. ...

Progress was slow. All day on July 3, for lack of favorable wind, the ships remained in sight of Alicante. On the 5th they had in view on the right the sierras of Granada, covered with snow, "even as the mountains of Tyrol are covered in the months of March and April." As they passed Malága the blue bay smiled, but the massive old Moorish fortification frowned down at them from its mountain |47| height, just as it glowers on travelers today. On the 8th, when near the towering rock of Gibraltar, the voyagers began to see the shores of Africa, topped by the twin peaks of Ceuta. Now came a serious setback. A west wind blew up so strong that the sails of the "San Nicolás" were torn away. Next morning the gale was so furious that no one could say Mass, and both vessels were driven back to the vicinity of Malága. In the space of three hours they had lost all the distance made in four days.

Kino, with his scientific turn of mind, was interested in all natural phenomena. The bright sea fish especially engaged him. One evening some dolphins played very near the ship, "their great size exceeding that of an ox." Another sea-monster chasing the dolphins, and easily surpassing them in weight, swam entirely round the ship. "Its color was such as we had never seen before. It was dazzlingly white, yet partly green and alternately yellow, deep red and blue, and of such extraordinary brilliance that even when two or three feet, or more, below the surface of the water it seemed to rival the beauty of the rainbow."

One day fishermen caught a monster that would outweigh a large horse. It had a tail on its back, and by the Italians was called mala. Another fish caught "was a beauty to be admired by all," says Kino. "The color of its head and back was coral, strewn, so to speak, with silver stars, and the hue was exceedingly brilliant. Its belly was white, or rather ivory. Its sides were golden, variegated with green and blue. Its eyes were marvelously bright. You might have described them as splendid sapphires set in topaz and gold. In a word, the plumage of no bird, however gorgeous, could rival the beauty of this fish, so resplendent it was and so diversified with colors of every hue. Wonderful, we said, is God in His works."

Kino the mathematician now had opportunities to tryout his astronomy. One evening, before the moon rose, he observed several constellations, "especially those of the south ... Ara, Lupus, Centaurus, and similar ones which cannot so easily be seen in Germany." On board Kino played with his mathematical instruments. One day he and some companions measured the Capitana. It was 168 feet long, 38 feet wide, 52 feet high, and had a mast 150 feet tall. Several times |48| he assisted in taking latitudes. On one occasion his fellow astronomer was Captain Columbus. ...

The 13th was unlucky. A mist that night caused a deviation from the true course. Just at the mouth of the Straits the pilot mistook an African mountain for one in Spain, and consequently steered south, straight to the African shore near Ceuta. Next morning the error was corrected, and the Straits were passed. But disappointment lay ahead. That evening, when near the harbor of Cádiz, they saw a Spanish fleet of forty-four ships only a short distance away. It was the Flota, sailing for the Indies.

The hearts of the Jesuits sank. This was the fleet in which they hoped to take passage for New Spain. But they were too late. As it passed before them the fleet eclipsed the setting sun, a sinister omen. |49| "When we saw this melancholy spectacle, we at once guessed its import, and most of us abandoned the hope of departing from Europe during the coming year."

There were still other delays. At dark that night they were almost at the entrance to the harbor of Cádiz. But it took four days to get inside, on account of bad weather and the strictness of immigration laws, particularly during the epidemic that was in progress. In attempting to enter, the sails were twice broken and the ship left in danger of going on the rocks. At last the storm abated. On the morning of the 19th port officials boarded the Capitana and examined ship and goods. "After an entertainment at the expense of our most illustrious Captain they granted to everybody the privilege of entering the city." Columbus knew the ropes.

Meanwhile Father Pedro Espinar, a procurator of missions for the Indies, came out in a boat to conduct the missionaries to the Jesuit college. He had eagerly awaited their arrival, for he had already paid 22,500 florins for their passage to Mexico. The fleet had sailed away without them and Father Espinar had to get his money back. He had also to write to the Father General in Rome to ask what to do with the missionaries until he could send them to their destination - which might be at least a year hence. And who would feed them during all this time? The procurator indeed had his troubles.

A week later Kino was at Sevilla. Whether he went by land or up the Guadalquivir River by boat we are not informed. Closing his diary on July 27 he told his provincial in Germany, "We shall wait for this decision [about sailing] in Sevilla, where we shall stay, just as if in a separate college, in the buildings and garden of the College of San Hermenegildo, whither our reverend father Pedro de Espinar conducted us from Cádiz four days ago." With his diary Kino sent a "crude geographical map" of their route. If they were not "too inelegant," he requested that both diary and map be sent to his dear old college at Ingolstadt.[7] |50|

Kino Diary - Genoa To Seville

Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino: Pacific Coast Pioneer

Herbert E. Bolton

Excerpts

The Way to the Indies

Chapter 9 Pirates And Sea Monsters

Chapter 10 The Veil Of Santa Veronica

Chapter 11 Strange Shapes In The Clouds

To download the entire chapters

Click

Kino Diary - Genoa To Seville - Bolton document (text)

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Original Diary of Mediterranean Sea Voyage

Latin Transcription by Dr. Peter Horwath

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Diary of Mediterranean Sea Voyage from Genoa to Cádiz

12 June 1678 to 14 July 1678

Latin Transcription by Dr. Peter Horwath

To view and download diary, click

Kino Mediterranean Diary

Spanish Flota Departs Cadiz To The New World

Jesuit Travel to New Spain (1678-1756)

Theodore E. Treutlein

.... Hundreds of Jesuit missionaries traveled the long way from their European provinces to New Spain. The body of letters and travel diaries which they wrote to the superiors of the Society and to their relatives and friends is one of the best sources for the study of one phase of colonial western hemisphere history, travel to New Spain. ...

Letters from overseas were circulated in the Jesuit colleges in Europe and the writer generally requested that the recipient of the letter as well as the members of the entire province remember him and his companions of the journey in their prayers. Hand-to-hand circulation of letters was but one way of spreading news from the travelers, however. Travel accounts were printed for wider distribution in "Der neüe welt-bott", [8] a German counterpart of the French "Leitres èdifiantes et curieuses" [9] and first edited by Father Joseph Stöcklein, S. J. The combined volumes of the "Welt-Bott" form one of the greatest sources extant for the study of seventeenth and eighteenth century travel and missionary activity. ... a source of information concerning the missions and as reports which stimulated men to become evangelists in foreign lands, the individual communications received from missionaries and those incorporated in the "Welt-Bott" had a considerable influence in causing still others to travel the long road from western Europe to the far-flung mission areas, among which the one of New Spain was conspicuous.

Eighteenth-century Jesuit missionaries who were going to New Spain from their German and Austrian Provinces traveled the well-established routes in coaches and wagons, aboard ships, on horse or mule-back, and on foot. [13] Journeying usually in groups they endured the weary toil of travel itself with food and water often scarce or lacking, and suffered the dangers of hostile populations, of pirates and privateers, of sea-sickness, storms, shipwrecks, earthquakes, drownings, and of yellow fever.

The route followed led first from the German or the Austrian Province to the city of Genoa where coaches were abandoned for ships sailing to Cádiz. From Cádiz the travelers sailed past the Canary Islands and then in the path of the northeast trade wind, somewhere near the twenty-first parallel, to the West Indies islands. Here a stop was made at Puerto Rico or Aguada on the Island of Puerto Rico, or at Ocoa on the Island of Santo Domingo. Then the voyage was continued directly to Vera Cruz, although on occasion a stop was made at Havana, Cuba. At Vera Cruz the missionaries mounted mules or horses and proceeded to Maltratta or to Jalapa, thence to Puebla de los Angeles, and |108| finally along a well-traveled "camino real" to Mexico City, the immediate goal of their journey.

If Vienna is considered a starting place, then the Jesuits can be pictured seated in the post-coach on its way to Graz. From there the route went through Trieste, Venice, Padua, Milan, and Pavia to Genoa. If they departed from a German Province the chances are they traveled singly or in pairs to some convenient starting place like Augsburg or Munich, riding in the post-coaches that far, and once in a group, bargaining with the driver of a "coach-and-four" to take them all the way to Genoa. Leaving Augsburg they would spend the first night in Landsberg, and from there continue through Innsbruck, via the Brenner Pass to Trento, through the Chiusa Pass to Roverto, to the Venetian border, and along the southern end of Lake Garda, through Brescia, Milan, and Pavia to Genoa. ....

At Genoa the missionaries, as many as forty in a group, boarded either an English or a Genoese ship and sailed to Cádiz. On this voyage many a missionary had his first experience with the sea and found to his discomfiture that one is not necessarily born a sailor. .... Under especially favorable conditions the voyage from Genoa to Cádiz might be made in about two weeks but more frequently the time required was nearly twice that.

Upon arrival at Cádiz, ships were quarantined before passengers were permitted to disembark. The length of this quarantine varied from five to ten days; if, however, an entering vessel had been exposed to infection, as long as a forty-day quarantine might be imposed. .....

Once in Spain the missionaries had to expect a long delay before they could secure passage to the New World. During |110| their stay in Spain the travelers were cared for in Jesuit establishments located in Puerto de Santa María and in Seville. ...

The sojourn in Spain was very important to the new missionary. During the time spent there, which varied from some months to as long as five years, he had the opportunity of adding to his native tongue and Latin a knowledge of the Spanish language, thus becoming tri-lingual. .. The new missionary had the opportunity of which he made good use to learn arts, crafts, and techniques, later to be taught to the natives. Also with his own hands he made trinkets of many kinds, and fashioned rosaries which were added to his stock of rings, mirrors, scissors, jew's harps, needles, and rosaries, previously purchased. [23] Too, he painted miniatures of saints to enrich his future church in the wilderness.

Father Ratkay, born a Hungarian nobleman, states in speaking of the two years spent in Seville awaiting departure for the New World:

"We studied not only astronomy, mathematics, and other interesting fields of knowledge, but we ourselves made all sorts of trinkets and worked at practical things. Some of us made compasses or sun-dials and others cases for them; this one sewed cloths and furs, that one learned how to make bottles, another how to solder tin; one busied himself with distilling, a second with the lathe, a third with the art of sculpturing; so that with those goods and skills we might gain the good will of the wild heathen and the more easily give them the truths of the Christian faith." [24] ....

[T]here were various circumstances and conditions outside the control of the Society which prevented an immediate departure to the mission areas. Sometimes the number of German Jesuits ready to depart from Spain exceeded the quota allowed; [25] crowded conditions on the ships kept others from securing passage. Shipwrecks on the |112| rocks in the port of Cádiz itself, the fear of pirates, and also the possibility of capture by privateers during the periods when Spain was at war with France or with England further delayed or prevented the departure of the missionaries. Then during the last years before the general suppression of the Society of Jesus, the opposition of relentless foes increased the difficulties of sending Jesuits to Spain's colonial possessions.

Before the Jesuits were allowed to leave Spain for the Indies it was necessary that they be given official permission to do so from the Spanish authorities at Madrid who approved the names of all who were leaving and sent them to the governor and consignor at Cádiz. ...

Cádiz, where were situated the commercial establishments of merchants who "commuted" there from their palatial residences in Santa María, was the exclusive port of departure for ships on which the Jesuits sailed to America between the years 1680 and 1755. [29] It was not an easy harbor for a sailing vessel to clear because of reefs in the roadstead where more than one ship was wrecked before it had fairly got under way. ...

An earlier group of missionaries leaving Cádiz in 1680 had not been so fortunate for their ship struck on a reef. On this occasion cannons were fired as signals of distress and the Jesuits were taken ashore in small boats. This calamity meant that they were faced with the prospect of another interminable delay. The father procurator immediately appealed to the president of the merchants, to the admiral of the fleet whom he reached in a skiff, and again to the president, in an effort to get passage for the missionaries - but all to no avail. In desperation he awakened the fatigued missionaries in the dead of night and suggested that they row to the fleet and plead in person to be accommodated.

Accordingly, led by their superior and praising Christ, the Lord, for giving them the opportunity of going forth to preach the Gospel in His example and in the examples of the Apostles Mark and Luke, without bag or baggage, without bread or money, and without double coats, the Jesuits rowed out to the becalmed fleet and asked the captains of the various ships for passage. One captain refused their appeal, another took two aboard. So they made the rounds, going from one ship to the next, but when all had been hailed there were still twelve missionaries who could not find passage and who were forced to return sorrowfully to shore. ...

Travel diaries of the Jesuits indicate that ships sailing to Vera Cruz in the summer months invariably made better time than did those leaving Cádiz in the winter. [32] Reasons for this are found in the meteorological conditions which are more favorable during the summer months than at any other time of the year for an Atlantic crossing under sail in the north-east trade wind belt, and also for navigation in the Caribbean Sea and in the Gulf of Mexico. [33] Winter or summer, however, almost every crossing was made perilous by storms. Valuable cargo was jettisoned to lighten vessels; sails were slit and masts cut off to prevent capsizing.

Besides the danger from storms, the depredations of corsairs and privateers were the greatest hazard to a safe arrival in ports of the Americas. This menace was present only between Spain and the Canaries and in the Caribbean Sea where, generally, marauders confined their activities. ... Pirates infested the Caribbean and Gulf waters, however, despite the efforts of Spain to drive them out, and the royal fleets and merchantmen had to be constantly on guard when in West Indies waters. ...

When the islands were approached, the fleet proceeded carefully, anchoring at night to avoid sailing on a reef, and maintaining a careful watch for pirates. At Puerto Rico, Aguada, or Ocoa the ships remained for a few days provisioning, making repairs, and, in general preparing for the final difficult portion of the voyage to Vera Cruz. ....

The usual route among the islands followed the north shore of Puerto Rico and then proceeded via the Mona Passage between Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo and along the south coast of that island. The Windward Passage between Santo Domingo and Cuba was less frequently sailed, perhaps from fear of pirates who were known to use the Island of Tortuga as a base. Ships rarely chose the Old Bahama Passage along the north coast of Cuba but followed the south coast instead. Frequently the Cayman Islands were sighted, much to the relief of the pilots apparently, since if they were not sighted there was the danger of |119| running upon them accidentally. ...

After crossing the Campeche Sound all eagerly awaited the first sight of snow-capped Orizaba. Finally the voyagers neared the treacherous port of Vera Cruz. The "capitana" fired two cannons, whereupon the port pilot who was maintained there by the king came to meet the fleet and guided it through the tortuous reef-lined channel to the anchorage before the fortress of San Juan de Ulua. Until three or four anchors were imbedded in the weak bottom and lines fastened to the bastion of the fortress a vessel was in grave danger, for a sudden north wind, a further hazard of the port, might catch the ship directly astern and force it aground. In this manner many who had come the great distance from Europe lost their lives at the goal, while the people of Vera Cruz watched, helpless to send aid in the face of the high waves of their shallow port. ....

The missionaries also were as well taken care of as the rather poor accommodations to be found in Vera Cruz permitted. Their resident brother Jesuits and representatives of the Mexican provincial received them eagerly and conducted them to the Vera Cruz college which was so small that on one occasion, at least, the Vera Cruz Jesuits were obliged to sleep in the church choir until guest rooms for the newcomers could be made ready for them. [52] The average length of the stay in Vera Cruz was eight days. This was presumably a rest stop in preparation for the difficult journey to Mexico City, but it had some of the aspects of an enforced delay since the mules and horses which were to carry the missionaries inland had to be brought from the interior, as no grass suitable for the animals grew in the immediate vicinity of Vera Cruz. [53]

The travelers were quite ready to leave Vera Cruz when all preparations for the journey to Mexico City had been made, for added to the discomfort of cramped quarters in the Vera Cruz |121| college there hovered in that port a conspicuous danger from the dreaded illness, the "black vomit." Thus is yellow fever ...

When finally all their arrangements had been made for quitting Vera Cruz the missionaries mounted horses and set out by the northern or the southern route to Puebla de los Angeles. Horseback riding presented difficulties since most of the missionaries were as unfamiliar with this mode of travel as they had been with sailing on the open sea, but they complain less about this aspect of their journey than they do of the extremes of heat and cold, of the swarms of mosquitos and clouds of dust which plagued them en route. ...

During the rest stop of two or three days in Puebla they visited the cathedral church and the various Jesuit establishments, of which ultimately there were five. Here in Puebla, as previously in Spain, the missionaries heard accounts of the work of their predecessors in the missionary field, and found themselves inspired with new eagerness for the apostolic work ahead. ...

The remainder of the journey from Puebla to Mexico City is practically unrecorded in the diaries and letters of the missionaries. Three days were spent in traversing the distance and one of the stops made was at the Jesuit establishment of San Borja, about an hour's ride from the city. Father Bonani, in his eagerness to see Mexico City, borrowed a telescope and viewed the city through it from San Borja. [63] When at last they reached Mexico City some of the missionaries entered the College of San Pedro y San Pablo to continue their theological studies; others made ready at once for the farther journey into the northern mission areas; still others continued later to the Pacific Ocean port of Acapulco to embark for the Philippine Islands.

Theodore E. Treutlein

Jesuit Travel to New Spain (1678-1756)