Best Concise Kino Biography

"Eusebio Kino, S.J."

John J. Martinez, S.J.

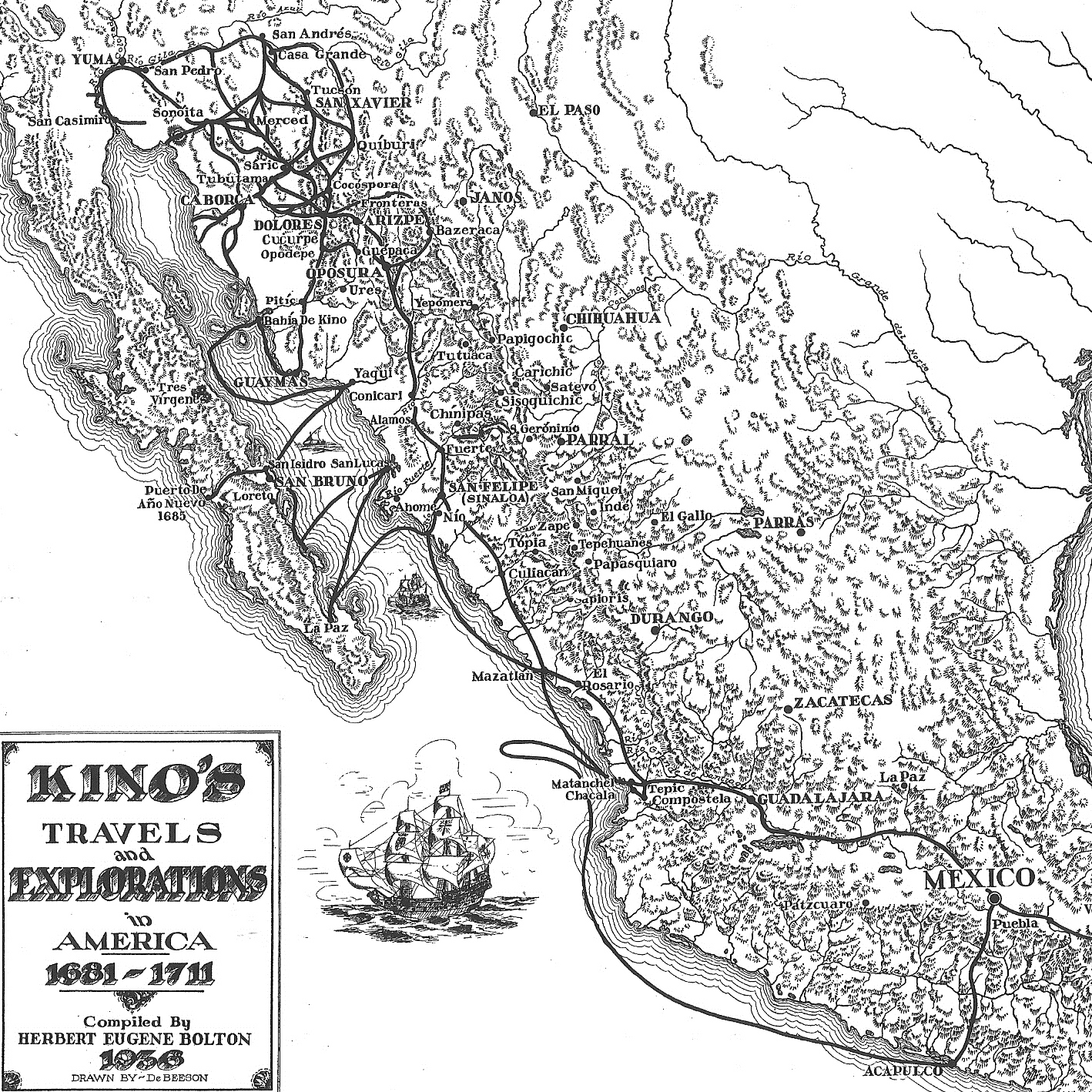

This account is written in a simple journalistic style makes Kino's story available to most reading age groups. Its author is Father John J. Martinez who was editor of the Jesuit magazine "America." It only 26 pages in the downloadable files below. It is the best short biography of Kino and includes history in a global context along with anthropological insights into the many cultures of Spanish colonial New Spain that Kino encountered.

To view online and then download, click

Best Kino Concise Biography document (pdf)

To download, click Best Kino Concise Biography document (text)

"Eusebio Kino, S.J. 1681-1711"

Chapter 10

"Not Counting the Cost: Jesuit Missionaries in Colonial Mexico, A Story of Struggle, Commitment and Sacrifice"

John J. Martinez, S.J

Eusebio Francis Kino was born in the mountain town of Segno, near Trent, Italy, on August 10, 1645. |1| His family was Italian, but the area was part of the Holy Roman Empire. Kino attended the Jesuit school in Trent, where the Jesuits were German, but instruction and conversation were in Italian. After Trent, he studied in Germany.

As a student, Eusebio became very sick, and he prayed to St. Francis Xavier, promising he would go to the missions if he recovered. When he recovered, he added Francis to his name and entered a German Jesuit province when he was twenty years old. His natural abilities were scientific, and he concentrated on mathematics and cartography with the hope of going to the China mission. Despite being offered the chair of mathematics at the University of Ingolstadt, he left Genoa, Italy, with other Jesuits in June of 1678, bound for Spain and New Spain. In July, they missed their connection with the fleet sailing from Cadiz, Spain, so they went to Seville to study Spanish, to make other preparations, and to wait for a ship.

One of the German Jesuits described Seville at that time, saying that the French and Dutch had a monopoly on industry and commerce. There were forty thousand French in the city, an amazing number of clergy and monasteries, and a multitude of beggars — the archbishop regularly fed twenty-two thousand people. Kino was in Seville for two years. When he finally left Cadiz in July of 1680, his ship grounded. He finally got away in January of 1681 and reached Vera Cruz, New Spain, on May 1, 1681.

A Jesuit just ahead of Kino described the trip by mule from the coast [143] through Puebla to Mexico City. They were received at an hacienda of the college in Puebla, which had eighty thousand hogs, twenty thousand sheep, and many thousands of cattle. Forty Jesuits lived in Puebla. This Jesuit wrote that in Mexico City the Jesuit church at the professed house shined with gold and contained so many fine pictures that there was hardly any empty space on the walls. The Colegio Maximo had 2,500 students. Although highly endowed, it had a debt of forty thousand pesos. He said that the Spaniards formed the ruling class and that the Mexicans were considered their serfs.

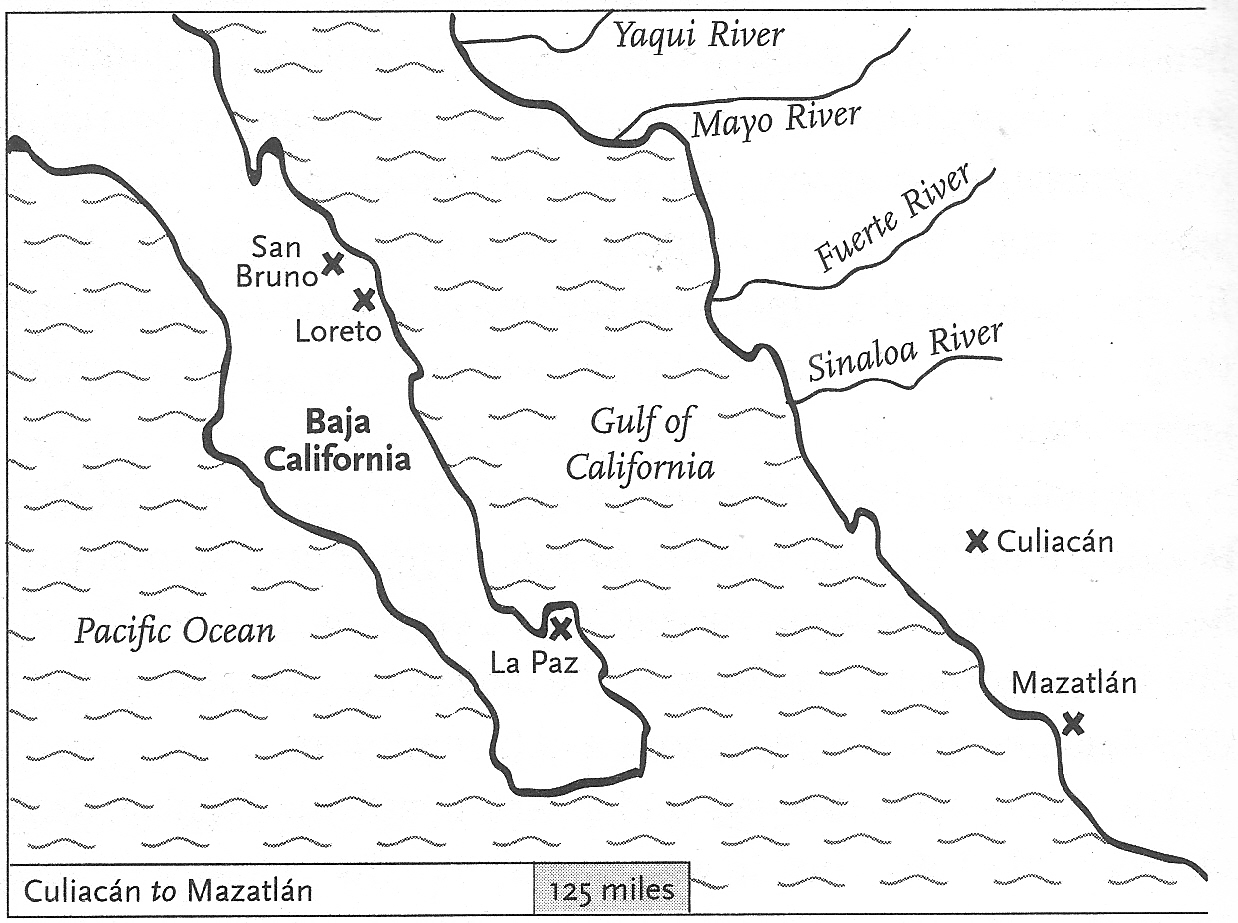

When Kino arrived in Mexico City, he was assigned to Baja California. Attempts to colonize Baja California had been unsuccessful, and now a new effort was being planned by the archbishop of Mexico City, who was filling the vacant office of the viceroy. The plan, approved by the government in Spain, looked more toward evangelization than economic profit. Isidro Atondo was in command of the expedition, with the title of admiral for California. He was also governor of Sinaloa, and he retained that position so that he could more easily obtain supplies.

Atondo built ships of sixty and seventy tons, with a launch for each, on the Sinaloa River, as well as a third smaller ship called a sloop. He was taking over a hundred people on the expedition, including thirty soldiers, twenty-four seamen, four pilots, three carpenters, two caulkers, one gunsmith, a surgeon, and a master bloodletter. There were Mayo workers, both men and women. Also included were two Jesuits — Eusebio Kino, as the superior of the two and as official mapmaker for the government, and Matthew Goñi, who had experience as a missionary in Sinaloa.

The people of the expedition were forbidden under pain of death to take anything from the natives, to trade with them, or to enter their houses. They could keep any gold, silver, or pearls that they found, but one-fifth of the value had to go to the king as tax. The armament of the expedition included eight canons and fifty muskets.

The ships were finished and pushed into the Sinaloa River on October 28, 1682, but it was several months before they reached California. They sailed south of Sinaloa State to the port of Chacala, [144 ] near Compostela, where supplies were being sent from Mexico and Guadalajara. When they left Chacala, it took two weeks to get up to Mazatlán. Then it took a month to sail to the Sinaloa River. Perhaps they were experimenting with the new ships.

At the Sinaloa River, they spent eight days taking on horses, cattle, fowl, and other supplies. They sailed at last on March 18, 1683, and were immediately becalmed for five days. Two days later they could see both shores, but it took another six days to reach the large bay at La Paz, Baja California. By this time, Kino had been in New Spain for almost two years.

That first night, everyone stayed on board. When some rowed ashore on Thursday morning, April 1, they found an area covered with reeds, human footprints, plenty of wood, and a spring. They returned to the ship.

On Friday, almost all the men went ashore. They fashioned a large cross and explored a little, but they returned to sleep on the ships that night. On Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, they went ashore and

|Map 22 Baja, Gulf of California & Sinaloa - link to map below| [145]

unloaded supplies. That Sunday, April 4, 1683, was Passion Sunday, two weeks before Easter. On Sunday, they explored the estuary of the bay. They saw smoke in the distance, and that evening they caught a great quantity of fish in a dragnet.

On Monday, Atondo took formal possession of the country in the name of the king, with as much pageantry as possible. Kino and Goñi took spiritual possession in the name of the bishop of Guadalajara. They then began to build a fort and a small church, and that night they remained on shore. Tuesday morning, while the crew was clearing a small elevation, they heard the shouting of native Californians. People appeared with war paint, bows, and arrows, and they made signs that the strangers should leave. The Spanish made signs that they had come in peace, and they offered to lay down their weapons. The native people refused to lay down their weapons.

The two Jesuits approached the people and offered crackers and necklaces. The Californians, who spoke the Guaicura language, gestured that they should put the gifts on the ground. The Californians then offered the Spanish men gifts of small, well-woven nets, some feathers, and roasted "mezcales," which were the vegetable hearts of a species of cactus.

On Wednesday and Thursday, the Spanish felled trees and tall palms. They had seen deer and rabbits, and they caught enough fish on Thursday to last three days. On Friday, eighty people came to visit. Kino made them welcome and offered corn, which was much appreciated. He showed them how to make the sign of the cross. When he gave a rubber ball to some of the children, they were frightened at first because they thought it was alive.

The people in Baja California did not farm. They ate wild seeds, worms, some insects, mice, bats, snakes, some wild plants, roots, and the fruit of some species of cactus. There were fish and oysters in the gulf, but only the people at the southern end of the peninsula had canoes for fishing. The other people had rafts made from bundles of cane like grass or from the light, pithy trunks of a local tree. They also hunted rabbit, squirrel, deer, and fowl. They had neither dogs nor pottery, but they made wooden bowls. With the heat and the scarcity of water, the people must have been among the poorest on earth. [146 ]

Friday evening, the native people went inland to sleep, and they returned on Saturday. In order to impress their guests, the Spanish set up a leather shield. An arrow could not pierce the shield, but a bullet from a musket could.

On Palm Sunday, Kino offered Mass and blessed and distributed palms.

On Tuesday, the admiral sent some soldiers to explore. Traveling six or seven miles, they found no rivers or native settlements, but from a hill they saw a lake, an attractive plain, and columns of smoke. On Wednesday, when forty Californians came to visit, many of them were new, and the Spanish offered them "pozole" (a corn soup or stew) and "pinole" (a cookie). In order to make pinole, corn was ground or at least pounded and crushed. It was mixed with sugar, and the dough was then fried or toasted over a fire.

On Wednesday and Thursday, many in the party went to confession, and they received Holy Communion on Holy Thursday. On Good Friday, some natives visited and brought a small load of wood because they had noticed that the Spanish gave gifts to those who brought wood. That evening, one of the priests gave a sermon in Spanish about the passion of our Lord.

On Holy Saturday, presumably late in the evening, they sang the litanies and celebrated the Mass of the Resurrection. They fired muskets and rang bells at the Gloria and at five other times during the Mass. On Easter Monday and Tuesday, they planted seed for corn, melons, and watermelons, and the two Jesuits started to study the language. The people of the area were the Guaicuras with the Guaicura language, and Kino eventually compiled a list of five hundred Guaicura words, ascertaining their meanings as best he could.

The people were poor because of the heat and lack of rain. The Baja receives only three or four inches of rain a year, as compared to twenty three inches in Mexico City, and more than forty inches along the east coast of the United States. However, there is more rain in the north of Baja California, especially on the Pacific side, and there is also more rain at the southern end of the peninsula.

In Baja California, the men went naked, and the women wore skirts [147] of reeds or skins, in the front and the back, from the waist to the knees. On the mainland, in contrast, the men usually wore at least loincloths, and the women wore fiber, skins, or cotton from the waist or shoulders.

In Baja California, infants were powdered with wood ash or partially buried where a fire had been, in order to keep them warmer. In the north, where it was colder, a person might have a shawl-made of sea otter or rabbit skin.

In Baja California, the people were living without huts or any shelter, and this fact surprised the Jesuits more than anything. Besides the warm weather, a second reason for the lack of shelter was that the Californians had to keep moving in order to find food, staying a week or so at each location. If there was a cool wind, they made a windbreak of rocks and slept behind it, and they often kept a fire going during the night.

A chain of mountains runs down through Baja California, from half a mile to over a mile high, with a few peaks in the north at ten thousand feet. This mountain chain is along the gulf side, and most of the Californians lived in the mountains.

The Spanish had first gone ashore on April 1. They caulked one of the ships, and on April 25, the admiral sent the ship to the Yaqui River for more horses and other supplies. Meanwhile, they made two exploratory trips of about twenty-five miles each, and they met a new people to the south, the Pericús, who were enemies of the Guaicuras.

As summer came on, the Spanish became worried because supplies were running short. Their crop had probably failed for lack of water, and the ship had not returned from the Yaqui River. Their third smaller ship had not sailed with them, and it was still trying to find them. Moreover, relations with the Guaicuras had deteriorated.

There was some stealing by the Californians. Then, when a mulatto cabin boy, John Zavala, disappeared, the people to the south informed the Spanish that the Guaicuras had killed him. When a Guaicura shot an arrow at a soldier, the admiral took him prisoner. The Guaicuras were angered by this, and 150 of them came armed to the camp. However, there was no fighting.

Next, fifteen Guaicuras came to the camp with signs of peace and sat down to eat. The admiral thought they had come to rescue the prisoner, [148] and since he believed that they had killed John Zavala, he ordered that a canon be fired at them. He killed three people and wounded others. These murders ended all relations with the Guaicuras, and it was difficult for the Jesuits to relate to the people of La Paz for many years to come.

The Spanish now had fear of the Guaicuras to add to their worry about supplies. The soldiers asked to return to Sinaloa because they did not want to remain while the last ship went for supplies. The admiral finally agreed, and they left on July 14, 1683. They had been three and a half months at La Paz, and it took a week to sail back to the new port of San Lucas, north of the Fuerte. Kino sent a map of part of the California coast to the viceroy.

They found out later that the Guaicuras had not murdered John Zavala. When Zavala had met some sailors, probably pearl fishermen, he traded a pearl for a canoe. He then paddled, apparently by himself, 120 miles across the open Gulf of California to the mainland.

The admiral started to gather supplies for another attempt to colonize Baja California. He replaced some soldiers with fifteen others from the fort at Sinaloa. In the same area, he recruited thirty-eight civilians, including some female slaves. Native Americans could be legally enslaved if they were involved in a rebellion. They could also remain slaves with the Spanish if they had been slaves within one of the indigenous nations.

It was on Wednesday, September 29, 1683, that they departed the second time for California. This was a dangerous time to leave, because during August, September, and October there were often sudden, destructive windstorms on the gulf. By the evening of the next day, they were only fifteen or twenty miles from shore, but they could see California. They then went across rather quickly and spent some days looking for a port, as one ship was leaking. On Tuesday, they anchored at a spot they called San Bruno, fifteen miles north of the present town of Loreto. They were about 165 miles north of their first settlement at La Paz.

On Wednesday morning, October 6, 1683, they went ashore. There was a river, but it had no water because it was the dry season. They did find water by digging in the sandy riverbed, and then twenty [149] Californians appeared who were very friendly and more relaxed than the people at La Paz. These Californians were Cochimís, members of the third language group in Baja California, who extended far to the north. They were much more numerous than the Guaicuras and the Pericús.

On Thursday, fifteen horses were put ashore. When ninety Californians appeared, they helped the party to unload, and they brought water. They were curious about the Spaniards and wanted to board the ship, so some went in the launches. That evening, the party slept on shore, and a small group of Californians, men and women, slept nearby with their children.

During the following days, the Spanish were getting organized. They built a primitive chapel, and on Sunday, two hundred Californians were at Mass. They were attracted by the paintings in the chapel, especially that of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and they invited the newcomers to visit their village.

During this week, there were also some unsettling events. On Monday, a dog with the party bit a Californian. Then, that evening, a Sinaloa man disappeared. His wife was worried and weeping, but he returned after a few days. It seems he was angry about something. Then, on Thursday, two Californians shot arrows at a horse. They wanted to see if an arrow could pierce the skin of a horse — it could. When a whole village came to stay on Friday, October 22, Kino had to tell them that things were not yet ready.

On November 8, the first Catholic marriage was celebrated in Baja California, between two Native Americans from Sinaloa.

The settlers had come ashore on October 6. They spent all of October and November building shelters. Later in November, the admiral sent a ship to the mainland for supplies. Blessed with favorable winds, it went over in three and a half days and returned in thirty hours.

Eusebio Kino and Matthew Goñi had started work on the languages. Actually, there were two different languages at San Bruno and to the south. The language at San Bruno was Cochimí, which Kino studied, and this language extended through the central and northern part of Baja California. Eventually Kino produced a short vocabulary, grammar, and catechism. [150]

These languages were difficult because the different dialects of the language could differ from one village to another, as much as Spanish differs from Portuguese. For example, in four different Cochimí villages, the word for people was "tamo," " tama," "tomo," and "tamoc." This is only one word, but it appears that the consonants were fixed more than the vowels.

Matthew Goñi was studying Monquí, a Guaicura language found to the south of San Bruno and south along the coast to La Paz. In the middle of the next August, Goñi went with a ship to obtain supplies. He returned with a new Jesuit, Augustine John Copart, who worked on the Guaicura language for four months. He put the extensive notes of Goñi into a treatise with the grammar, vocabulary, prayers, and so on.

After the first two months, on December 1, 1683, Admiral Atondo and Kino set out to explore Baja California. They took provisions for twelve days. Also in the party were twenty-five soldiers as well as five Mayos, six Cochimís, and six Guaicuras. They took six pack mules and fourteen horses, five of which were armored.

On the first day, they traveled to the northwest about eight miles to a site that was later called San Juan Londo. There was water here and good pasture. In fact, they later set up a second base here, mainly for the care of the animals. That evening nine new Cochimís joined them, and some of the other Californians returned home.

On the second day, for the first time on this second trip to the Baja, they saw flowing water. On the third day, they reached the wall of a mountain that the horses and mules could not climb. So they left six soldiers with the animals and proceeded on foot, carrying as much food as they could.

Very early the next morning, they climbed the mountain. They had to use ropes to haul up the weapons, the food, the admiral, and a few more people. At the top, they looked out over a beautiful plain. They then walked about ten miles to a water hole, where they rested and took a nap. In the afternoon, they went a few more miles. They saw some villages, but the people had fled in order to avoid contact. Then they came to a lake and made camp.

The admiral decided not to go farther. The next morning he stayed by the lake while Kino, five Mayos, and fourteen soldiers and ensigns [151] carried provisions for two days. They found another lake, and they met some armed Californians who were reserved but not hostile. There would be a future mission in this area called Purísima, and Kino noticed that the language was Cochimí, the language he was studying at San Bruno. They then returned to San Bruno.

Two weeks later, Kino rode with twelve others, soldiers and Mayos, up the coast. They were looking for a pass through the mountains that horses and mules could manage. After traveling a great distance in three days, they found a pass and also a large settlement of Californians. They returned in time for Christmas.

During the next twelve months, work went on at San Bruno. Over three thousand adobe blocks were made. They were putting up buildings, and during this time there was only one light rain shower. They did grow some melons, but the results of farming were meager or a failure. They planted in the riverbed. These crops were covered by windblown sand, and they had to carry water to their other plants.

The admiral kept discipline at San Bruno. A soldier stoned an Indian for a small offense, and the admiral caned the soldier. A native stole a sheep and was caned by the admiral. Atondo had a Mayo woman flogged, and Kino protested. When some natives chased a soldier, the admiral pursued them and killed a native. Kino, upset by the conduct of the admiral, wrote that the admiral regarded what be had done as a courageous and manly deed.

The next December, on the fourteenth, they set out to explore across the peninsula to the Pacific Ocean. They were forty-three in number, including nine Mayos and a few California guides. They had ninety-one horses and mules. Among the horses, thirty-two were armored with bull hides and five were armored with metal; there were twenty-nine soldiers with leather jackets for protection.

They first had to get over the Sierra, which blocked the coast from the rest of the peninsula. The Sierra in this area is three hundred miles in length, and it is called the Sierra de la Giganta, going as high as six thousand feet. It can be seen from the Yaqui River in Sonora, but only at sunset. They went up the coast to the pass they had discovered the previous year, but it was still very difficult with the heavily laden [152] mules. Some of the animals fell, and it took three days to descend from the pass.

It took two weeks to cross the Baja. The way was rough and stony, and the horses often went lame. A lot of time was spent in repairing the horses' shoes, and the men often had heavy work in preparing a path by clearing away bushes and filling in holes.

As they proceeded across the peninsula, the native people sometimes disputed their passage. However, with conversation and presents the native people were won to friendship and acted as guides. The party came to a riverbed. There had been virtually no rain at San Bruno, but at this spot there were springs that fed water into the riverbed. They continued their journey in the middle of the boulder-strewn riverbed between canyon walls, arriving at the Pacific on December 30, 1684. After exploring north and south along the ocean, they arrived back at San Bruno on January 13, 1685, after a trip of one month.

In the middle of December, just as Kino and the others left for the Pacific, one of the ships went to obtain supplies on the mainland. The other ship had been away for a whole year. It had gone for repairs, and the captain of this ship was also communicating with the interior of New Spain in order to obtain pearl fishermen. The smaller, third boat was also away, so the party at San Bruno was marooned.

During these months, the situation went from bad to worse. Supplies were very low, and many soldiers had swollen gums from scurvy. The water holes that they had dug in the sandy riverbed were turning foul.

In February, the admiral made a long trip down the peninsula looking for a better spot. He was also looking for an easier way through the mountains to the west. He found neither. At the end of March, one ship and the smaller boat returned to San Bruno. There was good food now, but the water kept getting saltier. In April, there was an appalling epidemic. Some of the party died, and others were paralyzed. The majority were sick.

Atondo asked the opinions of the others, and all were for leaving except Kino. Kino thought that the sick should be taken to Sinaloa but that the colony should be maintained. During the year and a half that [153] they had been at San Bruno, Kino and Goñi had baptized only eleven people because they thought that they might not be able to stay.

The admiral decided to leave because he believed that the land was too sterile to support a colony. Also, it was impossible to remain so dependent on Sinaloa and Sonora, and money was running out. The whole effort had cost 225,000 pesos.

They packed up. Getting the livestock on board was a huge effort, but the Californians helped, and many of them wanted to go along. The admiral refused all except for two boys to study more Spanish and to go north by ship with Kino to look for a better site for a colony. After they left on May 8, 1685, there was a reaction among the Californians against those who had been friendly to the Spanish, and some of the friendly Californians were killed.

Kino was on the second ship back to Sinaloa. They dropped the sick off at the Yaqui River and were there a month before they sailed for further exploration. They went over to the California coast and then north before returning to the Sonora mainland. They had contrary winds for a month. Kino visited the Seri people at the Sonora River. The Seri language was related to the Cochimí language, and the Seris could have come across the gulf at some time in the past over a chain of islands. The chain ended at the Sonora River with the very large island of Tiburón.

Kino's ship returned to the Yaqui and took on board some of the recovered soldiers. They were going to take them south, but first they stopped back at San Bruno to leave off the two boys. Everything was green at San Bruno because it had rained. They then went to warn a ship from the Philippines that there were pirates in the area, and finally Kino was back in Mexico City.

Kino recommended that the next effort in California be made with smaller ships and a small garrison. He thought that Loreto, south of San Bruno, would be a good location because it had more water, and he suggested an agricultural base on the mainland for the support of California.

Kino thought he was going back when the government promised thirty thousand pesos a year for California. When the money was used [154] for something else, he asked to work with the Seris because he saw their land as a stepping-stone to California. However, he was assigned to the Pimas |in own language O'odham|, with whom he would do the great work of his life. He was forty-one years old, and he would serve in the Pimería for twenty-four years.

Kino was a person to whom the Pimas responded with confidence. He was physically tough, prayerful, and very disciplined. He slept on some sheepskins on the floor of his room, with his saddle as a pillow. His diet was plain, and he used neither tobacco nor alcohol. A Jesuit who worked with him said that Kino spent a lot of time in prayer.

During his twenty-four years in the Pimería, he made more than thirty-five expeditions. He could ride for sixty or more miles a day for weeks on end. He spread horse and cattle ranches among the Pimas over the north of Sonora and the south of Arizona. He baptized forty-five hundred people and would have baptized fifteen thousand more if he could have provided the people with priests.

He did this while often having to refute false charges brought against both himself and the Pimas. He was sometimes criticized by fellow Jesuits, who may have been jealous of his success. And he was always defending the Pimas against calumnies. If the Apaches did some raiding, people would accuse the Pimas. It would have been an excuse to dispossess them and to use them as slaves in the mines and on the haciendas.

He sometimes traveled with Europeans, but more often with the Pimas. He rode with up to 120 horses, mares, and colts. With many horses, the riders could easily take fresh mounts, and the horses were an emergency source of food. Also, Kino left the mares and colts in different villages to start herds. The idea was that the people were preparing to receive a missionary.

The horse was as highly valued by the Native Americans as it was by the Europeans. The Indians would go to the mines to work for two things — horses and cloth. They used the horse for travel rather than as a farm animal, and some preferred the meat of horses and mules to beef. It may have been closer to the taste of the game to which they were accustomed. [155]

Kino disposed of thousands of animals as if they were his own, but there was a more communal notion of property. The idea was that mission property was for the use of the native people and in trust for them. He shared livestock with villages all over the Pimería, and he sent great numbers of cattle and horses to the later mission in California.

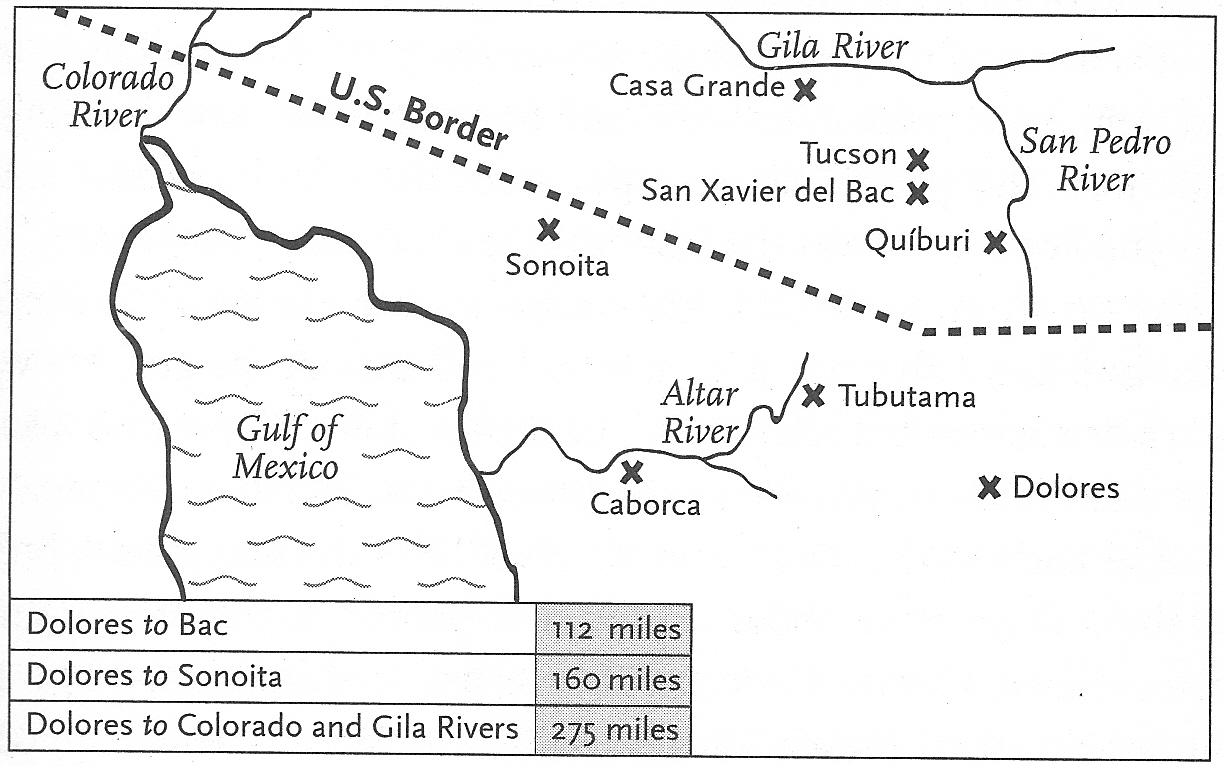

Kino was often away from his home parish at Dolores, but the people at Dolores went on producing a great deal of wealth. Kino also traveled beyond the Pimas to the Yumas on the Colorado River, and he crossed the Colorado and met some of the people on the other side. The Colorado, running south to the gulf, is almost the boundary between Arizona and California.

All of these people asked for missionaries. One time a group came from Upper California. They traveled down the gulf to a spot opposite Dolores, where Kino was located. Since they were afraid to cross the 170 miles of unknown land to Dolores, they sent a message asking Kino to come to them. He was away at the time and received the message too late. The visitors, who were living on what fish they could find in the gulf, started to go hungry, and they finally went back to California.

Kino was situated at Dolores, once called Cosari, in the Parish of Our Lady of Sorrows, in a corner of the Pima territory. To the south and to the east were people who spoke Cáhita languages, and farther east were the Apaches. So Kino looked north and west. This suited him, because he was also interested in helping the missions in Baja California, although he never succeeded in making contact with Baja California by land around the gulf. He dreamed of winning the whole desert area for Christ, including Upper California. There were about thirty thousand people in the rectangle from Dolores north to Tucson and west to the Gulf of California and the Colorado River.

Kino was positive and optimistic in his writings. He promoted the importance and dignity of the Pimas and the need for more missionaries. He did not discuss any internal problems at Dolores.

Kino left Mexico for this new mission on November 20, 1686. In Guadalajara, he spoke with public officials. Other Jesuits had told him that the recently converted were being enslaved and forced to work in the mines. He wanted as much relief from this abuse as he could obtain [156] for any people he worked with. He found that a decree had arrived from the king granting an exemption for the recently converted from twenty years of any forced labor. He took with him an official copy of the decree.

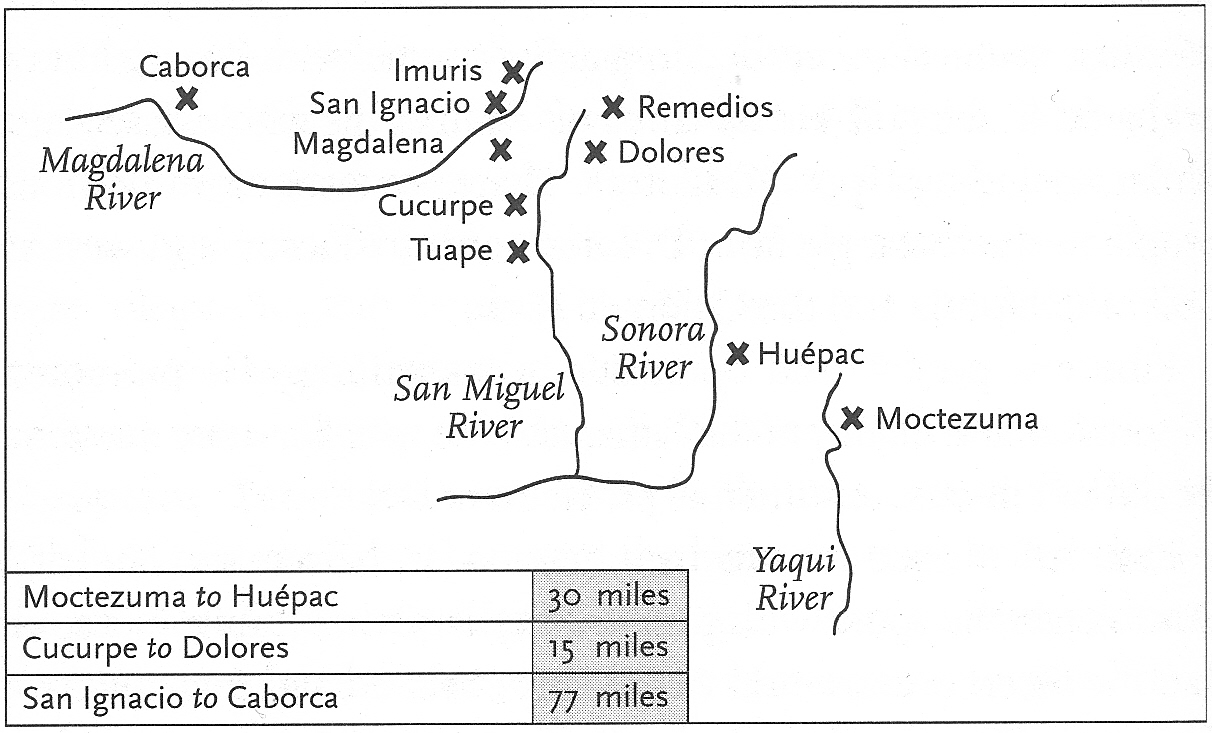

Kino arrived at Conicari on the Mayo River on February 15, 1687. At the end of the month, he went to Moctezuma, then called Oposura, on a tributary of the Yaqui and two hundred miles upriver from where the Yaqui empties into the gulf. The vice provincial, the elderly Manuel Gonzalez, was here. He was Jesuit superior of the whole Sonora area, and the two men would work together for fifteen years. By chance, Father Joseph Aguilar, also elderly, was visiting at Moctezuma. He was the missionary who was working farthest to the north.

The three Jesuits mounted and set off. They first stopped at the mining site of San Juan, only a few miles west of Moctezuma, where Kino was introduced to the Spanish governor of the area and where there was a garrison. They went farther west about thirty miles to Huepac on the upper Sonora River to visit the Jesuit who would be Kino's local superior, an Irish Jesuit working under a Spanish name, John Muñoz de Burgos. Going farther west to the San Miguel River a tributary of the Sonora, they rode north about thirty-five miles through

|Map 23 Pimería Alta: Southwest; link to map below| [157]

villages attended by Father Aguilar to Cucurpe. This village, where Aguilar lived, was the last Christian village, and none of the people in this village were Pimas. They all spoke a Cáhita language.

To the west of Cucurpe, stretching 120 miles to the gulf, is a desert. To the east were mountain chains, tributaries of the rivers to the south, and many people. To the north were the Upper Pimas with no missionaries. However, this would not be the first Jesuit missionary work with the Pimas. There was a Pima village far south on the Sinaloa River whose people Tapia and Pérez had met when they first came to Sinaloa. Several villages of people — called Lower Pimas, or Pimas Bajos — were located on the Yaqui River above the Yaqui Nation. Further, there were a few villages of Pimas on the middle Sonora, and all of these people were called Pimas Bajos. It was the Spanish who called them Pimas; their name for themselves was O'odham.

Father Aguilar had contacts with the Upper Pimas, or Pimas Altos, and they were waiting for a Jesuit. The three priests set out from Cucurpe on March 13, 1687. It was only about fifteen miles up the San Miguel River to Dolores, then called Cosari. Cosari was the home of Cacique Coxi, who had prestige and some authority over all of the Pimería. The cacique was away at the time, but the people gave the three Jesuits a warm welcome.

The next morning, Gonzalez returned to Moctezuma, and Kino and Aguilar set off on a seventy-five-mile circular trip through the villages for which Kino would be responsible. They rode west eighteen miles in this mountainous country to San Ignacio on the Magdalena River, which flows directly west and is a tributary of the Concepción River. They went upriver to Imuris, then to Remedios on the San Miguel, and then down to Dolores.

Protected by mountains, Dolores was in a river valley with good land. Kino had seed and stock from other missions to sow fields and to start herds. He also started to build and to instruct in the catechism. For this work, Kino had the help of two brothers who were Pimas Bajos. They were Francis Pintor, a catechist and an interpreter, and Francis's brother, who was blind and an excellent catechist. [158]

That first spring, Kino and a hundred people from Dolores went to Tuape to celebrate Easter. At the end of April, Kino made a circuit of the other villages of San Ignacio, Imuris, and Remedios. He did not travel much farther than this during his first four years. He was also learning a completely new language.

The two children of Cacique Coxi were among the first who were instructed and baptized. Cacique Coxi and his wife were baptized on July 31 of that first year, the feast day of St. Ignatius of Loyola. It was a big occasion, and five caciques came for the ceremony and celebration.

There were many Spanish in the area at mine sites and haciendas to the east and south. From the beginning, there were rumors and calumnies about the Pimas, which Kino had to refute. Kino was not specific about who started the rumors, but in general, it was said that the Pimas did not need missionaries, that they were few, that they were moving away, that they stole horses, or even that they were rebelling.

Almost from the beginning, Kino asked for more Jesuits. The first help arrived at the end of 1689 with three Jesuits, but new Jesuits did not always stay. They might have trouble learning the language, or the whole situation might be more than they could manage.

At this time, the provincial sent Father John Salvatierra to be visitor, or regional superior, and he asked him to investigate Kino and the Pimería because of the contradictory reports he was receiving. The meeting of Kino and Salvatierra was important, and Salvatierra would be the founder of the permanent California mission.

John Salvatierra was born in Milan, Italy, on November 15, 1648. His father was a Spanish official, and his mother was from a noble Italian family. Salvatierra had traveled to New Spain as a seminarian before Kino, and he did his theology at Puebla. He was ordained, did tertianship, and was sent to the Chínipas area in 1680, still a year before Kino arrived in New Spain.

Salvatierra spent ten years in the Sierra Madre, from 1680 to 1690. Then he was named vice provincial, or superior, of Sinaloa and Sonora for three years, and it was at this time, Christmas Eve 1690, that he and Kino met. He was three years younger than Kino. [159]

The two Jesuits decided to see the situation in the Pimería firsthand. They started from Dolores on a trip of some 225 miles. They rode west to visit a new Jesuit at Imuris, where there were seventy families, then to San Ignacio on the Magdalena River, and then farther west another forty miles to visit the Jesuit on the Altar River, which, like the Magdalena, is a tributary of the Concepción River. Kino was now in new territory, and it was his first long journey in the Pimería.

They went farther to Tubutama, where there were five hundred people and a new Jesuit. At a fiesta on January 6, 1691, the Feast of the Epiphany, there were in attendance many chiefs of the Soba people, who made up the western part of the Pima nation and extended to the Gulf of California. The goodwill of these people would later make it possible to explore the west of Arizona to the Colorado River. The Jesuits continued up the Altar River and were invited to visit some villages across what is now the international border in Arizona. Here they were again approached by Pimas and invited to go another forty miles to Tumacácori and San Xavier del Bac just south of Tucson, Arizona. They did go to Tumacácori. They did not go to Bac but returned to Dolores.

Salvatierra was impressed by everything he saw. He saw the goodwill and peaceful nature of the people. He saw their desire to become Christian and the need for more missionaries. Also, on the trail together,

|Map 24 Pimería Alta - Arizona & Sonora; link to map below| [160]

Kino shared his enthusiasm for California, and it was to Baja California that Salvatierra would go, almost seven years later, in October of 1697. He would work there for twenty years, except for a three-year term as provincial. Salvatierra would die on a trip from California to Mexico in 1717, sixty-eight years old, six years after the death of Kino.

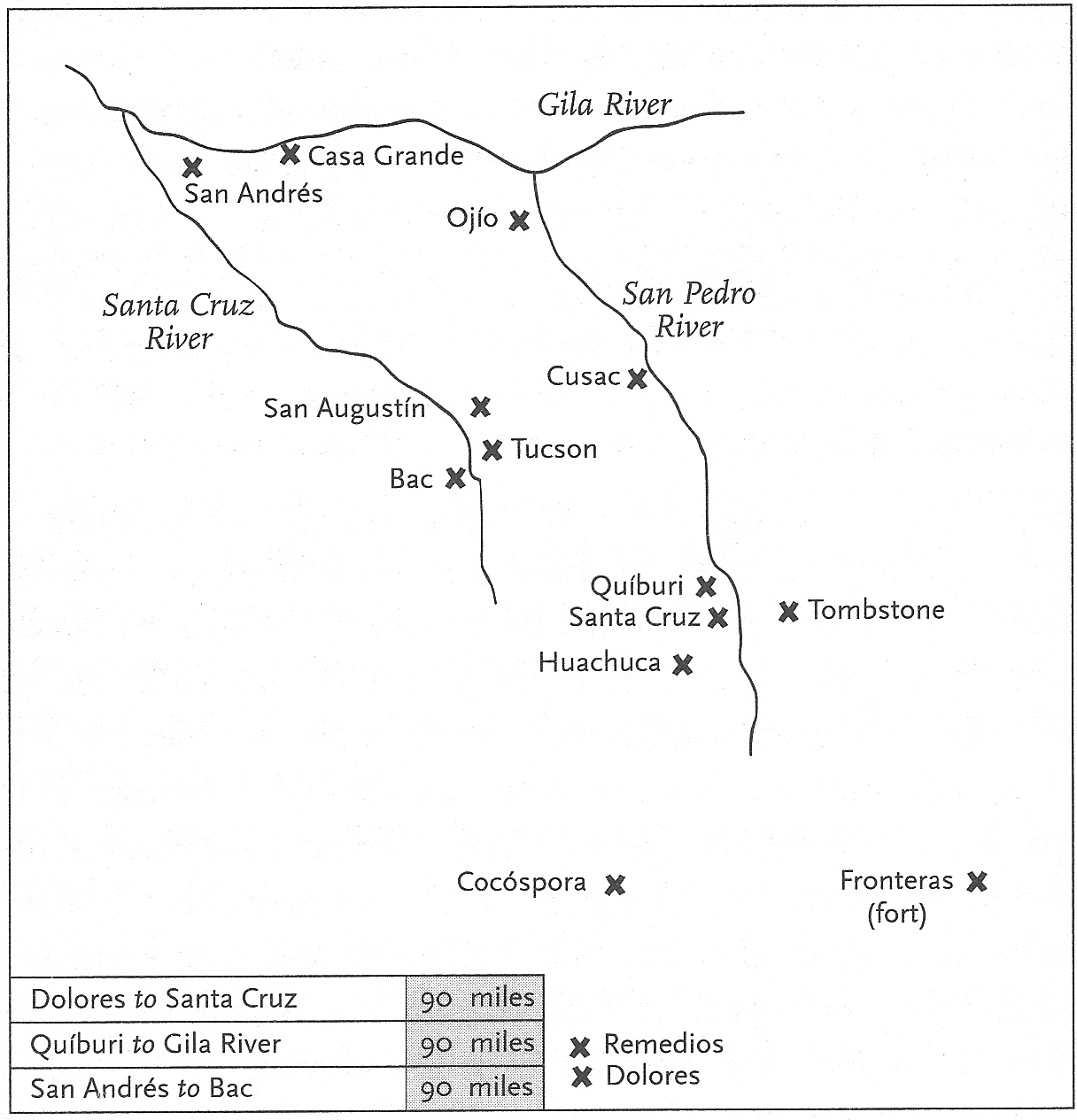

The next year, in the summer of 1692, Kino made his first journey to San Xavier del Bac, south of Tucson, where there were eight hundred people. Then he went southeast to visit the important Cacique Coro at Quíburi on the San Pedro River, about thirty-five miles north of the border. The San Pedro River, which flows north to the Gila River, was the Pima front line, facing the Apaches. All of these people were part of the eastern Pimas.

Kino was kept busy building, and also helping missionaries. In April of 1693, the adobe church at Dolores was dedicated, and many Spanish and Native Americans came for the celebration. The Irish Jesuit who was the local superior sang the Mass.

Toward the end of 1693, Father Augustine Campos arrived and would spend several decades in the area. He was the most important Jesuit after Kino. In order to introduce him to the people, Kino invited Campos to go with him on a long trip to Cacique Soba, ruler of the four thousand Soba people, or western Pimas.

At this time, Kino proposed a peace treaty between the warring eastern and western Pimas in order that there might be a united front against the Apaches, and the peace proposal was accepted. Kino and his party then went many more miles west, and from a mountain they saw the Gulf of California. The people at this spot were friendly, but some were frightened because it was the first time they had seen Europeans.

After his return to Dolores, Kino talked to civil authorities in Sonora about building a ship at Caborca in order to explore the gulf. He was given a new arrival as a companion, Lieutenant John Manje, who would write many fine journals of his explorations with Kino in the Pimería.

Manje and Kino left Dolores in March of 1694 with supplies to build the ship. There were about a thousand people in the area around Caborca, Except for the Concepción River and its tributaries, they were in a vast desert. However, Kino thought that Caborca would support [161] three thousand or more people. During their stay at Caborca, Manje and Kino went sixty miles farther west to the shore of the Gulf of California.

They left the logs for the ship at Caborca to season, and on the way back to Dolores they came across the remains of a prehistoric site called Trincheras. In June, thinking that the timbers would be seasoned, they returned to Caborca. Manje went north to explore while Kino worked on the ship. A letter came from the local Irish Jesuit superior telling Kino not to continue with the shipbuilding. He probably thought Kino was too often away from his parish duties at Dolores. Kino obeyed, although he did have permission from the provincial.

During 1694, as was typical, there was continual warfare between the Opatas, Pimas, and Spanish on the one hand and the Apaches and other nations to the east and northeast on the other. The Opatas, Pimas, and Spanish were farmers, and the people to the east were nomadic.

In March, some herds of horses were stolen from the Sonora missions. The Pimas north of the future international border on the San Pedro were suspected. A lieutenant, not Manje, took a squad of soldiers to hunt for the horses and the thieves. Toward Bac they discovered Pimas cooking what they thought was the stolen horsemeat. They killed three Pimas and captured two, but it turned out that the Pimas were cooking deer meat.

In May, this lieutenant led 240 armed men against the Apaches. There were 90 soldiers and civilians, as well as 150 Opatas and Pimas. They killed sixty of the enemy and captured thirty as slaves for the mines and haciendas. Then at Tubutama, a village near Caborca, a Jesuit sent word of trouble. Two Pimas were haranguing the others. The lieutenant went with thirty soldiers, and he punished the ringleaders. Several Opata villages in the mountains to the east were attacked by the Apaches during this year. At one mission village, the grain fields were burned, and some old men and women were killed.

At a place called Cuchuta, east of Dolores, six hundred Apaches launched a massive attack. However, the Opatas, Spanish, and Pimas had been warned and were waiting for the attack. They ambushed the attackers and killed twenty-five. One Spanish soldier was killed. They later heard that many more of the attackers had died because the Pimas [162 ] had used poisoned arrows. This was part of life on the frontier. It was more dangerous than it once was because the Apaches and others had horses even if they did not yet have guns. However, all of this violence in 1694 was typical because there was really a continual state of war in the northeast of Sonora.

In the middle of October 1694, two new missionaries arrived at Dolores. One was Francis Xavier Saeta. Born in Sicily, he came to New Spain in 1692 and did his last year of theology. He was sent to Caborca. There were now six Jesuits in the area. A new rectorate was established with the superior at Cucurpe. Father Kino went with Saeta to Caborca to introduce him and to help him get started.

Toward the end of November, Kino made his first visit to Casa Grande on the Gila River northwest of Tucson. It is an ancient ruin, and Kino described it as a four-story building as large as a castle. Scholars believe that Casa Grande was built by the ancestors of the Pimas.

When Kino went on these trips, he took mares and colts. The people would have to wait a while, but this was one way to start a herd. Kino eventually established nineteen ranches in the Pimería as far as Sonoita and Bac. Meanwhile, Saeta made an enthusiastic beginning at Caborca. He and the two hundred people at Caborca were founding and building the future town. Within a few weeks they had made five hundred adobe bricks.

Kino had promised Saeta a hundred cattle, a hundred sheep and goats, saddle and pack animals, twenty mares with their colts, 120 bushels of wheat and corn, and household effects, all of which he would deliver a little at a time. Kino asked Saeta to consider about 10 percent of the stock as in trust for the California mission, which did not yet exist.

Kino had also asked Francis Pintor to go with Saeta to help him. Pintor was the catechist who had been with Kino since he arrived. He and his blind brother were Pimas Bajos from Ures on the Sonora River. Pintor had ridden with Kino and Manje on some of their expeditions.

Saeta soon realized that the supplies from Kino would be insufficient. So at the end of November, he made a begging trip around the missions. Kino headed the subscription list, promising another sixty cattle, sixty [163] sheep and goats, 120 bushels of wheat and corn, and more mares. Hogs are not mentioned. Kino had attempted to introduce hogs at Dolores, but the men did not wish to care for them. They assigned the task to the women, who could not manage the animals, and one woman was hurt.

Saeta was not neglecting religious instruction. He wrote:

My children attend Mass every morning and catechism twice a day, adults as well as children. They work with all love. I have planted a very pretty garden plot in which the little trees (a gift from Kino) are set out and the vegetable seeds planted for the refreshment for the sailors from California.

Kino invited Saeta to Dolores for Holy Week services and for a rest, but Saeta begged off. Later, he suggested to Kino that they meet halfway. He wrote to Kino on April 1, 1695, and the next day he was dead.

The trouble started at Tubutama, about fifty miles upstream from Caborca. This is the place where two people were punished and probably hanged the previous year. The Jesuit there was Daniel Januske. With him he had three Opata overseers, as it was the custom to employ experienced cowboys and herdsmen as overseers in new areas. There was great tension at Tubutama between the Pimas and the newcomers.

Things blew up on March 29. Father Daniel had left to observe Holy Week at Tuape. An Opata herdsman knocked down and kicked the Pima overseer of the farm. The Pima shouted to his friends, "This Opata is killing me." They attacked the Opata and killed him. The Pimas killed the other Opatas.

The Pimas burned the church and the priest's house, desecrated sacred articles, and slaughtered mission cattle. They then started for Caborca to clear all foreigners from the area. It was not an organized revolt but a group of angry people.

Saeta received word of the destruction, and he thought it was a deep raid by some group from far to the east. He heard that a man and a boy from Dolores had been killed. They were returning to Dolores after having brought cattle to Saeta from Kino.

Others — a group of more than fifty — joined the Pimas as they came south on Holy Saturday, April 2, 1685. They went to Saeta's quarters [164] and talked with him, acting peaceful. When he went to the door with them, they shot him with two arrows. He went back inside, picked up

his crucifix, and fell on the bed, where they shot him with more arrows.

They then killed Francis Pintor, who, as much as anyone, had been evangelist of the Upper Pimería. They also killed the two Opatas who were overseers at Caborca. After they sacked Saeta's house and stampeded the cattle, they returned upstream. Francis Xavier Saeta is buried at Cucurpe.

During this time, Kino was suffering with a fever at Dolores, but he arranged with the Spanish that there would be peace if the Pimas handed the ringleaders of the group that killed Saeta and the Opatas over for punishment. However, some people in the government thought that rebellious Indians should be soundly punished. The governor was persuaded, and he broke his agreement with Kino.

The Pimas and the soldiers met at El Tupo, about twenty-five miles west of Dolores, on June 9, 1695. The ringleaders were handed over. The soldiers then surrounded the fifty Pimas who had brought the ringleaders in and were unarmed. Three other Pimas started to point out accomplices of the ringleaders. This was not part of the agreement. Manje, who was an eyewitness, wrote that the lieutenant drew his sword and struck off the head of one of the accused. This act of violence panicked the Pimas. They tried to escape, and the soldiers shot them down, killing forty-eight. Kino wrote that thirty were innocent of any complicity in what had happened to Saeta and the Opatas.

The lieutenant in charge was the same person who had killed one of the three people who were cooking deer meat near Bac by mistake. He had also punished and probably hanged the two people at Tubutama the previous year.

Later, when the soldiers left the area to continue their struggle against the Apaches, the Pimas rose in fury. They destroyed what was left of the buildings at Caborca. They burned the churches and houses at Imuris, San Ignacio, and Magdalena, but they did not attack Dolores, Remedios, and Cocóspora, which were under the care of Kino.

The soldiers returned to put down the rebellion. The Spanish feared that it would engulf all of Sonora and that the Spanish would be driven [165] out, as they had been from New Mexico only fifteen years previously. However, the Pimería was not isolated like New Mexico. Also, the uprising was not an organized rebellion. The people were enraged about what had happened at El Tupo, and bands of Pimas were destroying the establishments of the five Jesuits in the area. However, the records do not mention that they actually killed anyone, and the caciques, including pagan ones, were not committed to a rebellion.

An army of a few hundred Spanish and Native Americans gathered to put down the uprising. The army marched west, but the soldiers found no army to fight, although they attacked Tubutama, killing twenty-one people and destroying the crops in the area.

The army then moved south to Caborca, where the people had had nothing to do with anything that had happened. Their food supply had been damaged by the raiders from Tubutama, and then it had been destroyed by soldiers who came after the death of Saeta. These people were scattered in the mountains and deserts, and some of them were begging for food in different villages. They feared to reassemble at Caborca until Kino was called in to reassure them. Finally, there was a big meeting, and peace was reestablished.

On November 16, 1695, Kino, fifty years old and now seven and a half years in the Pimería, set out on a trip to Mexico. He rode with young Pimas, including the son of the cacique of Dolores. They rode the twelve hundred miles to Mexico in seven weeks instead of the usual three months, and Kino was able to offer Mass each day of the trip.

This trip was crucial because of the uprising and the massacre at El Tupo and because the mission was in danger of being abandoned. Kino's ideals and vision for the area are described in a book he wrote, just before leaving Dolores, about Father Francis Xavier Saeta, the slain missionary.

He attributed to Saeta the qualities that a missionary must have: a sincere affection for the people, a boundless generosity toward them, heroic endurance of the inevitable hardships, frequent prayer and meditation, avoidance of idleness, and the good example of a profound and well-ordered religious life. The Indians must see that the missionary is personally interested in them and that he will spend himself for their welfare, both temporal and eternal. He must not just [166] direct others, but personally share in the work of instruction, visiting the sick, constructing buildings, farming, and so on. The missionary life is a supernatural calling, and although divine assistance is more important than human effort, the former will not be forthcoming unless man does his part.

It is also important not to offend anyone, because the Indians make public whatever they know about someone. "On journeys to very distant regions I have met Indians whom I had never seen. They come up and say they already know me. This would happen even as I traveled farther from home. " |2|

As much as possible, there should be no military presence. Sometimes the soldiers are summoned to a disturbed area. By the time they arrive, the guilty have disappeared, and the innocent are often punished. The soldiers do not have to return with prisoners as evidence of their success. Law-abiding natives should see the soldiers as their protectors, not their persecutors. Also, as much as possible, the missions should be self-supporting.

One of the main purposes of both the trip and the book was to defend the Pimas. Kino said that there was not a general revolt but a raid on Caborca by a few people who had been abused. He described the cooperation of the Pimas to punish the guilty — cooperation that resulted in the massacre of innocent people at El Tupo and the consequent attacks on other missions.

Father Kino had a vision of a Christian and prosperous civilization that included Baja and Alta California, the Pimería and the Yumas, and all the people to New Mexico and beyond. He was thinking of the evangelization of California when he started to build that ship, and he persisted in his effort to find a trail through the desert to Baja California for livestock and people. On his journeys, he explained the faith and the sacraments. He also relied on trained catechists to spread the message. Lieutenant Manje was well educated and well read. If he was exploring on his own, he too would explain the faith. They used the cross and what pictures they had when they taught. [167]

Kino wrote:

Many of these poor people, despite their humble condition, on seeing and experiencing kind treatment will come to rely on the missionary with deep attachment, sharing with him the best of their possessions and food. Gradually they will place themselves and their families at the disposal of the missionary. These newly converted Christians, with striking simplicity and with less reluctance than other Indians and older Christians, hold in high esteem and awe what they had not heard before, such as the more extraordinary doctrines of our faith — for example, the resurrection of the dead, the never ending torture of hell for the wicked, the everlasting happiness of heaven given in reward to the good, and the divine creation or the universe, including all peoples, the sun, moon, heaven, earth, and all else. |3|

During his stay in Mexico, Kino met Salvatierra, who was stationed at Tepotzotlán. They still could not obtain permission for the evangelization of California, but the provincial did promise five Jesuits for the Pimería.

Kino arrived back at Dolores in the middle of May 1696. He sent word of his coming to caciques and Pima officials, and they had a big meeting and fiesta at Dolores in June. Kino brought greetings to the people from different officials in Mexico. These Pima leaders then helped Kino to harvest the ripe grain, as it seems they did every year.

Some were baptized at this time. Others were denied baptism as not sufficiently prepared. In order to show the loyalty of the Pima Nation, Kino sent the minutes of this assembly to officials in Mexico, together with a list of the Pimas who participated. He kept up with the paperwork.

The next spring, 1697, word came that Kino was going to California with Salvatierra. Civil officials protested loudly that Kino could not leave the Pimería. So he stayed, and the vice provincial asked him to prepare the way for new missionaries on the San Pedro River, east of Tucson.

That same spring, the cacique of Bac and two of his children came to Dolores to be instructed and baptized, and around that time Kino sent an oven to the people of Bac as a present.

In the fall, Kino and Lieutenant John Manje made plans to explore the San Pedro River. They and ten Pimas set out from Dolores after Mass on All Souls' Day, November 2, 1697, with sixty horses and mules and with three pack loads of provisions. One of the ten Pimas

|Map 25 Pimería Alta: East and North; link to map below| [168]

was an official at Dolores named Francis the Painter. He was a fine interpreter and catechist like Francis Pintor, who had died with Father Saeta two years earlier at Caborca. Perhaps he had taken the name Francis Pintor when he was baptized.

They headed first for Quíburi, which was ninety miles from Dolores as the crow flies. They went north through Remedios and Cocóspora, where there was a Jesuit. After a few more stops, they arrived at Huachuca, where eighty Pima residents received them hospitably.

Huachuca was about fifteen miles southwest of Quíburi, and at a later time there would be a U.S. fort at Huachuca with the Buffalo Soldiers (African American cavalry). The next morning they traveled to [169] the San Pedro River and stopped at Santa Cruz, a few miles south of Quíburi and across the river from the present-day town of Fairbank. A few miles east of Fairbank is the later mining site of Tombstone, where many movies would be made.

At Santa Cruz there were a hundred people. They had built an adobe house with a timber-and-dirt roof for a future missionary, and they were caring for a hundred cattle, which Kino had sent them. The next day, a Spanish captain arrived at Santa Cruz with twenty-two soldiers and a pack train. This was a diplomatic mission to meet and to see the peaceful nature of the people, but the soldiers were well armed, as they were on the frontier with the Apaches to the east. After greeting one another, they went a few miles north and downriver to Quíburi, where Cacique Coro gave them a big welcome.

At Quíburi, there were a hundred houses and five hundred people. Quíburi was fortified and situated on a bluff with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. The land was irrigated, and the people grew corn, cantaloupe, watermelon, other foodstuffs, and cotton. They wove the cotton into cloth, dyed it, and made clothes. They wore shoes made of animal skins.

When Kino's party arrived, they found the Pimas celebrating a recent victory over their nomadic enemies. Kino wrote that they found them to be very jovial and friendly, dancing over the scalps and spoils of fifteen enemies, Jocomes and Janos, whom they had killed a few days before. The captain, the sergeant, and many others entered their circle and danced with them.

That evening and the next days, both Kino and Manje spoke about the mysteries of the faith, and the captain spoke about matters of state and war.

When they left the following morning, they were accompanied by Cacique Coro and thirty of his armed warriors. The threat of an Apache ambush was serious, and it would be a ninety-mile trip down the San Pedro to the Gila River. For the first sixty miles north of Quíburi, the San Pedro River was mostly deserted because of hostility between Coro's Pimas and the Pimas on the San Pedro nearer the Gila. All the Pimas on the San Pedro were called the Sobaípuris. [170]

As they traveled, they had scouts out because they were afraid of being ambushed. Nomadic people lived in the mountains to the east of the San Pedro River and north of the Gila. The nomadic people had tents, and when they moved, a team of at least two big dogs dragged poles carrying a tent.

The party had sent messages that they were coming with peaceful intentions. Although Father Kino was now in a new territory, he knew some of the chiefs because they had traveled down to Dolores to be instructed and baptized. The first village they came to was Cusac, with seventy people and twenty houses. It was in a beautiful location with many cottonwood trees by the San Pedro. In the roughly thirty miles from here to the Gila River, there were ten villages with about 100 people in each village, except that the principal village of Ojío, near the Gila and under the Christian cacique Human, had 380 people and seventy houses.

At Cusac, Kino's party was received with crosses, arches, a swept road, and abundant cooked food. The visitors gave gifts of knives, needles, religious medals, and ribbons — valuable gifts at that time and place, and not too bulky to transport. They also had a bulkier gift of cloth.

There were talks about the faith and about loyalty to the Spanish government. These meetings, conversations, and instructions often went on all night. The travelers then went downstream another five miles to a bigger village, where they were warmly received and where a temporary lodging had been constructed of poles and mats. While Kino was baptizing four infants and some sick people who were in danger of death, Cacique Humari and numerous companions arrived. They had come down on foot from Ojío because there were not yet horses in these villages. All of the villages probably had goats and sheep, but the cattle and horse ranches extended to the south only from Bac and Quíburi.

The next morning after Mass, Cacique Coro and Cacique Humari publicly embraced and were reconciled. Then they all traveled north together, stopping at some villages, until they reached Ojío, where they had a big celebration. The captain gave a ribboned cane of authority to Cacique Humari. There was a long meeting in which many men spoke — the captain, Kino, Manje, Francis the Painter, Cacique Coro, and others. [171]

Having counted about two thousand people on the San Pedro, including children and infants, they decided to continue their exploration down the Gila to meet new people and to see the prehistoric ruin at Casa Grande. Cacique Coro and his thirty warriors went with them, and they kept sentries on duty during the night.

This part of the Gila was new to Kino, although he had been to Casa Grande from Bac three years earlier. After Casa Grande, where Kino offered Mass as he did each day, they continued down the Gila to San Andrés, where the cacique was a Christian who had traveled to Dolores to be instructed and baptized. They had passed two villages of about two hundred people each on this river, and there were four hundred people at San Andrés. Manje mentions that the people had cotton stockings, which were attached to their trousers so that they formed a single garment. The people also had clothing and shoes made from the skins of deer and pronghorns, which are indigenous animals similar to antelopes. Manje also noticed the shining pottery of these people.

The Pimas on these rivers seem to have been better off than the people of Sonora and Sinaloa were. They were certainly better off than the poverty-stricken and mostly naked Pimas who lived in the desert in southwest Arizona.

The party continued to the Santa Cruz River, and turning south, they traveled eighty miles upriver to San Augustín, where there were 800 people in 186 houses. After visiting here, they went on to Bac, where there were 830 people in 166 houses and where the houses were divided into three neighborhoods that formed a triangle. The people at Bac received them joyfully, even treating them to fresh bread baked in an oven that Kino had sent. At Bac, two of the Spanish officers purchased two Jocome captives, a girl of twelve and a boy of ten. From here, Cacique Coro, mounted on a new horse that the party had given him, left with his warriors for Quíburi.

On the way back to Dolores, the travelers stopped two days to work on the big church that was being built at Remedios. They were back at Dolores on December 2, after a journey of thirty days. They had traveled over five hundred miles and had counted almost five thousand Pimas [172] on the rivers. Kino had baptized eighty small children and eight sick adults who were in danger of death.

A few months later, on February 25, 1698, three hundred Apaches attacked Cocóspora. This is hard to understand because Cocóspora is about forty miles west of the fort at Fronteras. The raiders were deep in Pima and Spanish territory. They took a few horses, as well as smaller animals like sheep and goats, and burned the buildings. The Pimas and the Jesuit missionary were in a barricade, and only two Pimas were killed. However, after the raiders left, some Pimas went after them and were ambushed, and nine more Pimas were killed. A combined force of Pimas and soldiers then gathered and went in pursuit. They caught the raiders, killed thirty, captured sixteen, and recovered the horses and other stolen property.

A month later, on March 30, six hundred Apaches, Jocomes, Sumas, and Janos attacked Santa Cruz on the San Pedro River at daybreak. The raiders came mostly on foot. There were a hundred people at Santa Cruz and a hundred cattle. Four of the Pimas were killed, and the others barricaded themselves in a building. Santa Cruz was only about five miles south of Quíburi, which had a total of five hundred people, but the raiders, who included both men and women, were so numerous that they felt very secure. They made themselves at home in the village, butchered some animals, and started to cook a meal.

Word of the attack reached Quíburi, where many extra people had come from the west in order to trade. Cacique Coro and a large group of well-armed Pimas moved south to Santa Cruz. Facing so many Pima warriors, the Apache cacique proposed that each side choose ten men to fight each other, and the proposal was accepted. The ten chosen to fight for the raiders included six Apaches. The battle consisted of shooting arrows and dodging or deflecting the arrows of one's opponent.

The raiders shot their arrows well, but they were not nimble in avoiding the arrows of the Pimas. Nine of the raiders were killed or wounded, but no Pimas were hurt. In the end, it was one Pima against the Apache cacique. When the cacique was thrown to the ground and killed, the raiders panicked and fled. The Pimas killed fifty-four of the [173] raiders at Santa Cruz, thirty-one men and twenty-three women. Armed with poisoned arrows, the Pimas pursued the enemy for over ten miles, and only about three hundred escaped.

The battle was so extraordinary and the victory so complete that each side was shocked and even frightened. Cacique Coro moved his people to the west for some months before returning to the San Pedro, and the Apaches and their allies asked the Spanish for peace in El Paso and in New Mexico.

In September of the same year, an interesting meeting took place at Remedios, just north of Dolores, which reveals Kino at work. A statue had come to Remedios from Mexico, and Kino turned the dedication of the statue into a religious and civic celebration. The year before, there had been another great victory of the Pimas on the San Pedro against hostile people to the east. So Kino decided to dedicate the statue on the anniversary of this victory. Caciques and their families came from as far away as Casa Grande, and Kino also invited other Jesuits and Spanish officials.

All sorts of things were happening. Old friendships were renewed, and new friendships were made. Kino had an opportunity to preach about the faith. He also made arrangements for a long trip down the Gila to the Colorado River and south on the Colorado to the Gulf of California. A celebration like this revealed the generosity and hospitality of the Pimas at Dolores and Remedios.

At a celebration like this a cacique or a member of his family were to be baptized. Kino might ask a Spanish official and his wife to be godparents. In the Spanish culture, the godparents become coparents ("copadre" and "comadre"). It created a familial relationship.

Kino's religious superiors wanted him to explore the Colorado area because Salvatierra was now in California. They wanted to know if supplies could be sent to the Baja overland from the Pimería. Civil officials also wanted him to explore because there were rumors of a quicksilver mine in the area.

Kino, the cacique of Dolores, and seven other Pimas went on this expedition in October, and they took with them a Spanish captain as an official representative of the government. This captain was important [174] because he was an independent witness that the people were friendly, peaceful, and numerous enough to justify missionaries.

This trip produced the first written description of Papago land, or the Papaguería. The Papagos are related to the Pimas, and they received Kino's party with kindness. The people of the different villages guided them through the area as they followed the Gila River to the west. On this trip, Kino realized for the first time that the Gila flowed not into the gulf but into the Colorado River After going south to the village of Sonoita, they went farther west to a mountain. From this high spot, Kino saw that the Colorado flowed into the gulf. It was too hazy to see California.

During the following years, Kino made other expeditions, and he became friends with the Yumas on the Colorado. They were the biggest Indians Kino ever met. He crossed this river one or two times, but he was never able to open up a land route to Baja California. In 1699, Kino asked his superiors if he could go as a missionary to Upper California, but nothing developed from the request.

In October of 1700, Kino rode a thousand miles in twenty-six days. He was fifty-five years old. Also in 1700, he sent two hundred cattle to Baja California by ship. Each year he also sent fifteen mule loads of flour to California.

In this year, he asked for a replacement at Dolores so that he could live at Bac. Superiors said yes, and Kino sent seven hundred cattle to Bac. However, he never got to go. The superiors sent another Jesuit in 1701. In this year, Kino was named local superior, or rector, of a new rectorate in the Pimería, and Salvatierra came for a second visit. He wanted to find a land route to Baja California because shipping supplies to California was too expensive. He got permission from the various officials and obtained some soldiers. Then he sent word to Dolores that he was coming.

It was a big expedition. There were about 150 animals — horses and mules. There were forty mule loads of food and supplies. The personnel included Salvatierra, Kino, Manje, five Californians, ten or fifteen soldiers, and a great number of Pimas. They all met at Caborca, a hundred miles west of Dolores, where the cacique of Sonoita had sent four Pimas to bid them welcome and to act as guides. [175]

On March 11, 1701, they set out from Caborca for the trip north, over a hundred miles, to Sonoita on the international border. As they set out, they were in a good mood because it had rained recently and the desert was full of flowers. They sang on the trail. However, it soon became difficult for the animals. They had to go more than two days without water, and the animals were half crazed by thirst. Finally, the party found some water, and then they reached Sonoita.

From Sonoita, the way became more difficult. The animals again went two days without water until they found some by a poor village. Salvatierra said the land was black from ancient lava, full of boulders, and sandy. The animals were either damaging their hoofs on rough lava beds or sinking to their knees in the sand.

It was at this poor village that they celebrated Palm Sunday on March 20. The next day they left the animals at a water hole. The main party went on, and that evening of the twenty-first, their guides brought them to three springs. They were only a mile from the gulf. From a high spot they could see Baja California curving away from where they stood. They were convinced that the Baja was a peninsula and not an island. After a further attempt to find sufficient water for the animals, they were forced to give up and return.

In 1702, Kino lost four missionaries. Two of them left the area, and one died of sickness after a year at Tubutama. The fourth one, after a year at San Xavier del Bac, caught pneumonia and died. Kino spent 1704 building new churches at Remedios and Cocóspora, He sold cattle to raise 3,700 pesos, which he used to buy tools and cloth. Workers with their families came from as far as Bac to help build the churches. Besides daily food, Kino paid them with blankets and fabric.

In this same year, Kino and the Pimas of Dolores gave a charitable donation of silver, worth a thousand pesos, in order to adorn the tomb of St. Ignatius in Rome. They sent the silver to the provincial in Mexico City, and they asked him to forward it to Rome. Instead of forwarding it, the provincial used it to buy and to send to Dolores supplies that had not been requested. The provincial was afraid that the Jesuits would be accused of exploiting the Indians. [176 ]

In early 1705, while Kino was away, a Spanish lieutenant and his troops plundered Dolores. Some Pimas had moved to Dolores from other villages. The lieutenant took ninety of them and forced them to return to their original villages. He also stole grain, goats, and sheep. He said he would return later for the horses and cattle. Almost all of the ninety people returned to Dolores.

This lieutenant later tried to take corn from another village. When the leaders pointed out that they could easily join the enemy in the mountains, the lieutenant reported to his superiors that the Pimas had revolted. This caused a lot of commotion and wild rumors even as far as Mexico. The lieutenant was finally dismissed from the army.

Six other new churches were also being built in the Pimería in 1705. A Pima from Dolores went to Tubutama to oversee the making of the adobe bricks. Pima carpenters from Dolores helped at Magdalena, Caborca, and other places. Kino said that the carpenters were rather expert.

As Kino grew older, Manje, his friend and riding companion, became a general. Manje wrote a valuable book about his explorations in the Pimería. However, in this book he criticized the missions. He said that the missions were monopolizing the best agricultural land and that only the poorer land was left for the Spanish. He said that the Spanish had been defending the area with their property and their lives. He mentioned that the older missions had few Indians left. Where there were thousands, now there were only a few hundred. He recommended that the land be distributed to the Spanish. He also thought that the Spanish should be able to use the "repartimiento" system as in other places. This system meant that the Native Americans would be distributed to work for the Spanish. The system was hedged with laws; for example, it required just wages. However, it was forced labor. It often led to abuse and to the enslavement of the Native Americans,

Manje also criticized the Jesuits for not offering spiritual ministry to the Spanish and to their Indian servants This was a touchy subject. If the Jesuits ministered to the Spanish, they were accused of usurping the place and rights of the diocesan clergy. If they did not minister to the Spanish, they were accused of negligence. The Jesuit regional superior [177] reacted to all of this with the threat to pull the Jesuits out of Sonora. Since this frightened the Spanish, the governor of Sonora put the general in jail on a trumped-up charge until he modified his opinions.

In 1706, Eusebio Kino made his last two long expeditions. In January, he went with another Jesuit and a group of Pimas to the Gulf of California and down to Tiburón Island. Along this desolate stretch of the coast they met sixteen hundred Indians, some of whom were Pimas but most of whom were Seris and Teporas. The Indians were affable because some of them had visited Caborca and a few had even been to Dolores. Kino baptized some infants and sick adults, and he invited the Indians to move to Caborca since their land was somewhat sterile. They said that they would do so little by little.

In October of 1706, when Kino was sixty-one years old, he traveled about five hundred miles round-trip to the north of the gulf and near the Colorado River in order to meet some new people. On this trip, caciques of the Yumas met with him at Sonoita, where people were caring for a herd of cattle in expectation of a missionary.

During his last few years, Kino was doing pastoral work, writing, and producing maps.

In March of 1711, Eusebio Kino rode over to Magdalena to dedicate a chapel. In the middle of the ceremony he became ill, and soon after he died. Sixty-five years old, he had spent twenty-four years in the Pimería. He is buried at Magdalena, where a mausoleum was erected over his grave site in his honor.

Pimería After Kino's Death

1712-1767

After the death of Kino, there was a decline. Then, after 1730, there was a revival with the coming of Swiss and German Jesuits, but this renewal did not include Kino's parish at Dolores. Dolores, its "visita," and Remedios, were depopulated by epidemics, and Dolores was eventually abandoned.

In 1736, there was a big silver strike at a village called Arizonac in the Pimería, which brought many more Spanish to the area. Some years after this date, a Jesuit reported that twenty-eight of the ninety-two Jesuit mission parishes in New Spain had no government stipend. [178]

In 1749, a colonel arrived from Spain and came to the area intent on gaining wealth. His first act was a campaign against the Seris. He enslaved them and sent many of them to the south. He then appointed a Pima, who had fought with him against the Seris, as native governor of the Pimería. This Pima had a free hand. The colonel was indifferent to the area and did not visit it. There was general disorder in the area, and people became contemptuous of Spanish authority.

The Pima whom the colonel had appointed finally organized a revolt. The rebels killed Father Thomas Tello at Caborca on November 24, 1751. He was from La Mancha, Spain, born September 17, 1720. He entered the Society before he was fifteen years old and he was thirty-one when he died.

A few days later, the rebels killed Father Henry Ruhen at Sonoita. He was born January 16, 1718, and entered the Society when he was eighteen years old. He was from Borssum, Germany. He died when he was thirty-three years old.

One of the unhappy results of this rebellion was that the unity of the Pimas Altos was broken. As time went on, violence continued between the Spanish and the Apaches. Jesuit Michael Sola had an unhappy experience with the Apaches. He was stationed at a village near the fort at Fronteras. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from New Spain, he wrote in Europe about what had happened.