Kino Horseman

Kino: Endurance and Long Distance Rider

Herbert E. Bolton

Kino's endurance in the saddle would make a seasoned cowboy green with envy. This is evident from the bare facts with respect to the long journeys which he made. Here figures become eloquent.

When he went to the City of Mexico in the fall of 1695, being then at the age of fifty-one, Kino made the journey in fifty-three days. The distance, via Guadalajara, is no less than fifteen hundred miles, making his average, not counting the stops which he made at Guadalajara and other important places, nearly thirty miles per day.

In November, 1697, when he went to the Gila, he rode seven or eight hundred miles in thirty days, not counting out the stops. On his journey next year to the Gila he made an average of twenty-five or more miles a day for twenty-six days, over an unknown country.

In 1699 he made the trip to and from the lower Gila, about eight or nine hundred miles, in thirty-five days, an average of ten leagues a day, or twenty-five to thirty miles.

In October and November of the same year, he rode two hundred and forty leagues in thirty-nine days. In September and October, 1700, he rode three hundred and eighty-four leagues, or perhaps a thousand miles, in twenty-six days. This was an average of nearly forty miles a day. Next year he made over four hundred leagues, or some eleven hundred miles, in thirty-five days.

Thus it was customary for Kino when on these missionary tours to make an average of thirty or more miles a day for weeks in a stretch, and out of this time are to be counted the long stops which he made to preach, baptize the Indians, say Mass, and give instructions for building and planting.

A special instance of his hard riding is found in the journey which he made in November, 1699, with Leal, Gonzalvo, and Manje. After twelve days of continuous travel, supervising, baptizing, and preaching up and down the Santa Cruz Valley, going the while at the average rate of twenty-three miles (nine leagues) a day, Kino left Father Leal at Batki to go home by a more direct route, while he and Manje sped a "la ligera" to the west and northwest, to see if there were any sick Indians to baptize. Going thirteen leagues (thirty-three miles) on the eighth, he baptized two infants and two adults at the village of San Rafael. On the ninth he rode nine leagues to another village, made a census of four hundred Indians, preached to them, and continued sixteen more leagues to another village, making nearly sixty miles for the day. On the tenth he made a census of the assembled, throng of three hundred persons, preached, baptized three sick persons, distributed presents, and then rode thirty-three leagues (some seventy-five miles) over a pass in the mountains to Sonóita, arriving there in the night, having stopped to make a census of, preach to, and baptize in, two villages on the way. Next day he baptized and preached, and then rode, that day and night, the fifty leagues (a hundred and twenty-five miles) that lie between Sonóita and Busanic, where he overtook Father Leal. During. the last three days he had ridden no less than one hundred and eight leagues, or over two hundred and fifty miles, counting, preaching to, and baptizing in five villages on the way. And yet after four hours' sleep he was up next morning, preaching, baptizing, and supervising the butchering of cattle for supplies. Truly this was strenuous work for a man of fifty-five. ....

To Kino is due the credit for first traversing in detail and accurately mapping important sections of California and the whole of Pimería Alta. Considered quantitatively alone, his work of exploration was astounding. During his twenty-four years of residence at the mission of Dolores he made more than fifty journeys inland, an average of more than two per year. These tours varied from a hundred to nearly a thousand miles in length. They were all made on horseback. In the course of them he crossed and recrossed repeatedly and at varying angles all of the two hundred miles of country between the San Ignacio and the Gila and the two hundred and fifty miles between the San Pedro and the Colorado.

When he first opened them most of his trails were either absolutely untrod by civilized man or had been altogether forgotten. His explorations were made through countries inhabited by unknown tribes who might but fortunately did not offer him personal violence, though they sometimes proved too threatening for the nerve of his companions. One of his routes was over a forbidding, waterless waste which later became the graveyard of scores of travelers who died of thirst because they lacked Father Kino's pioneering skill. I refer to the Camino del Diablo, or Devil's Highway, from Sonóita to the Gila. In the prosecution of these journeys Kino's energy and hardihood were almost beyond belief. ....

He was usually well equipped with horses and mules from his own ranches, for he took at different times as many as fifty, sixty, eighty, ninety, one hundred and five, and even one hundred and thirty head. A Kino cavalcade was a familiar sight in Pima Land.

Herbert Eugene Bolton

Excerpt from "Rim of Christendom - A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino: Pacific Coast Pioneer"

Chapter CLII: "What He Had Wrought"

To download Bolton's entire chapter

Chapter CLII: "What He Had Wrought"

Kino's Achievements (4 text pages),

click Achievements

Jane Waldron Gurtz

Great Article on the History of the Barb

To read and download a great article about the Barb horse in history with beautiful era paintings, click

https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/200701/the.barb.htm

"The Barb horse was the most desired horse breed by European royalty and was the "horse" of Carthage, Rome, Muslim and Christian Spain and also "the horse" of Native People and cowboys of the American West. The Barb is called the Spanish horse, the Spanish colonial horse, Indian pony and the wild mustang. The Lippizaners of Austria are cousins to the Barb."

Jane Waldron Gurtz

"The Barb"

Aramco World

January / February 2007

Richard Collins

The Barb - The Ranch Horse

Much of what we know about Sonoran horses of the Jesuit/Spanish era comes from the German Jesuit Ignaz Pfefferkorn, who worked in the Pimeria Alta forty‑five years after Kino's death. With typical Germanic thoroughness, Pfefferkorn described the many fine qualities of the Spanish Barb: relatively small, sturdy and strong boned, proud and fiery, swift and gritty, yet easily tamed. The one preferred for everyday road travel, the “caballo de camino” had a speedy yet comfortable gait, so comfortable in fact that Pfefferkorn claimed he could ride right along, holding a cup of water without spilling a drop. ...

Later on, the sturdy Spanish Barb became the foundation horse for most of the or the Quarter Horse breed used today on western ranches, as well as for horse shows, rodeos, and cutting contests. But the show horse and ranch horse can differ by a country mile. Show people look for pretty, fat, and slick; the rancher, vaquero, and cowboy look first at the feet, legs, and back for soundness. One of my better ranch horses had a head shaped like an ironing board, and hair like rusty wire. His big, black hooves never lost a shoe, he never needed the vet, never missed a day's work, and never became friendly.

The early version of the ranch horse also conspired with the landscape to produce today's icon of western Americana, the cowboy.

Richard C. Collins

Riding Behind the Padre: Horseback Views From Both Sides of the Border

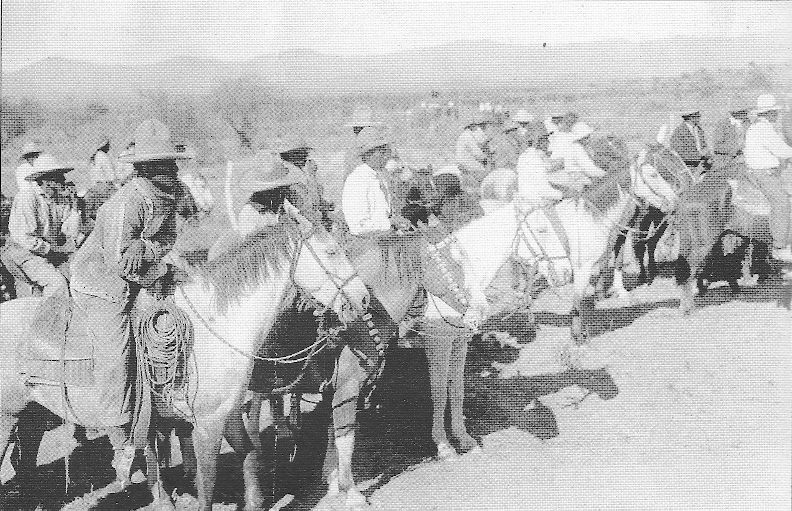

Start of the Cattle Roundup

O'odham Cowboys On Their Barb Horses

Father Kino's Mustangs

Frazier Hunt and Robert Hunt

North America's first really famous endurance rider was an Italian-born Jesuit padre named Father Kino. He was also called Brother Eusebio, and in the narrow valleys and great desert stretches of the Sonora-Arizona border country they still speak of him and his miracle rides.

He was almost thirty-nine years old when he arrived in Vera Cruz with a number of other Jesuit missionaries. That was on May 3, 1681. Cortez and his band of adventurers had unloaded their sixteen horses at the same spot 162 years before. The progeny of those original sixteen horses and the ones that shortly followed now numbered into the hundreds of thousands. Vast privately owned ranches and numerous mission farms and ranges in Mexico and the Texas lands had become fertile breeding grounds for numberless short-coupled, sturdy, tough horses.

They still differed little from the original Spanish-Barb horses that Columbus and his successors had brought to the islands of the West Indies and then transplanted to Florida and Mexico and the lands to the northward. By Father Kino's day, these horses had become fully acclimated, and the old law of the survival of the fittest had weeded out many of the unworthy and the incompetent.

Kino certainly had had no schooling as a horse and cattle raiser, and little or no experience as a horseman who could train and manage these tough, strong-willed Spanish-Mexican ponies. He had, oddly enough, acquired considerable fame as a mathematician and map maker, and shortly after his arrival in Mexico City he was ordered to the west-coast district of Sinoloa to explore by boat the east coast of Lower California. The problem of whether this land was an island or a peninsula was then a much mooted one. Before Kino died he was to settle the question for all time.

He had been in Mexico five years when he was sent north to plant missions and ranches in the unknown and isolated area known as Pimeria Alta. This unmapped region roughly comprised an area 250 miles square that included what is now northern Sonora and southern Arizona, lying north and south between the Altar and Gila rivers, and from the San Pedro River on the east to the Colorado River and the Gulf of California on the west. It was largely a harsh, waterless, cruel land; inhospitable, lonely, and isolated. But here were the heathen Pima Indians, and close by, the warlike Apaches. Lost souls they were, with the little father ready and eager to save them.

Kino picked up his horse and sheep beginnings from older mission ranches on his way north. He also did one other vital thing; at Guadalajara, he obtained from the Royal High Court a formal written order that no Indians converted by him could be forced to work in the mines. This document was as important to the hard task that lay ahead as was his band of horses and sheep; it was second only to his sacred mission of conversion.

For all his devoutness and humble service to his Lord, the little missionary was a superb manager, builder, leader, and horseman. In the twenty-four years he lived in this faraway land, he baptized four thousand Indians, built and stocked a dozen beautiful missions and self-supporting farms and ranches, explored and mapped Lower California, and left astounding records of travel and horsemanship. It is this last, of course, that wins him a place in this book.

He was almost forty-two years old when he established his mother mission at Cosari, some hundred miles below the Sonora-Arizona border. He named it Nuestra Senora de los Dolores and it was his headquarters until he died. From it he embarked on more than forty great trips by horseback, many of which meant journeys of from one thousand to almost three thousand miles.

For the most part, he traveled with only a few Indian converts and possibly one or two Spanish officers. At times a brother-priest accompanied him. But usually he was alone, save for his trusted natives. On many of his trips he would drive hundreds of sheep and considerable horse stock on ahead, and plant them in some rich little valley where he would soon win over the Indians and build a farm and mission. On his ordinary inspection trips he would invariably start out with a good string of pack and saddle animals. For as much as thirty-six hours at a stretch he would make his way across deserts that were waterless deathtraps. Yet the uncanny little padre never failed to get through with his horses and his Indians.

He was fifty-one when he decided to go directly to Mexico City to plead for more missionaries and more missions for his Pima land. A few months before this a band of Indian malcontents had suddenly arisen, killed Father Xavier Saeta, and brought on a general uprising in Pimeria Alta. Alone, Father Kino stayed with his mother-mission, and while other establishments were plundered and destroyed Dolores was untouched. The revenging Spanish soldiers exacted a terribly penalty, but by November, 1695, peace was restored, and the padre started his long horseback journey to the capital with only a scant Indian escort. They rode the tough little mustangs that had been born on the open ranges and broken by Indian mission boys.

There was much work for the padre on his way south. There were sunrise Masses to be said, baptisms to be done, endless advice and orders to be given. Each night it would be dark when Father Kino unsaddled and laid his sheepskin saddle pads on the ground for his bed. At dawn he would be up, and the busy day would begin.

It was a roundabout way he followed to Mexico City, totaling almost 1,500 miles. Much of it was trail-riding over rough country, yet the middle-aged priest made the entire journey in fifty-one days. This meant an average of thirty miles a day, rain or shine, heat or frost, with every minute he was out of the saddle crowded with a hundred-and-one duties and ministrations.

He arrived in the capital on January 8, 1696, and a month later started the long journey home. This time he was accompanied by Captain Cristobal de Leon, who was killed by Jocome Indians long before the journey's end. Father Kino had turned aside to say good-bye to two brother- padres at a passing mission, when the attack was staged, and thus had escaped death.

Year after year Kino continued his tireless horseback journeys. He would pick a spot for a new mission and with only the humblest adobe hut as a beginning, he would start his plantings and horse and sheep industry. Shortly, as if by miracle, green fields, flocks and horse herds, and beautiful mission buildings would come to life. Always there were new horseback journeys to make, new missions to establish.

One of his journeys extended through the fifteen-day period from April 21 to May 6, 1700. The first four days, he covered the 140 miles between Dolores and San Xavier Mission, below the present city of Tucson. He was busy every spare moment, saying Mass, baptizing children, and comforting the sick and dying. On the fourth day, he laid out plans for a new church and rode fifty miles on to San Xavier.

After a crowded week he took up the return journey, riding fifty miles the first day, and reaching San Cayetano late that night. The following morning he had just said his sunrise Mass when a messenger came from Father Campos, his fellow-priest at San Ignacio, sixty-two miles away, with the word that the Spanish· soldiers had captured a runaway Indian and on the following morning would beat him to death. Kino finished his duties, wrote several letters, then called for his horse, and reached San Ignacio at midnight. He slept only a few hours when he was up to say his sunrise Mass and to throw the power of his presence into the fight to save the Indian boy's life. He won.

For a total of twenty-four continuous years, this indefatigable missionary-on-horseback rode across the burning sands, through hostile and friendly Indian lands, up tiny valleys, spreading his good words and good deeds. At sixty-five, broken in body but strong in spirit, the old father collapsed as he was dedicating a beautiful little chapel consecrated to San Francisco Xavier, that he had built at Santa Magdalena. Six days later he died.

Rev. Father Luis Velarde, who was his successor in the rectorship of Pimeria Alta, wrote with touching simplicity of how death came to this first great horseman of the continent:

"He died as he had lived, in the greatest humility and poverty, not even undressing during his last illness and having for his bed-as he had always had-two sheep skins for a mattress and two small blankets of the sort that the Indians use for cover, and for his pillow a packsaddle."

Many of the Spanish-Barb mustangs that Kino raised on the mission ranches of his beloved Pimeria Alta, along with other stolen mission horses, soon found their way far northward on the east or west side of the Rockies. Time and again native revolts would burst. into flame, and Indians would loot the missions and drive off the horses. The animals, along with the art of how to train and handle them, were traded to warlike tribes who spread this horse culture ever northward.

Within a generation after the death of Father Kino, many of the Indian tribes of the High Plains acquired the horses that in a few short years turned them from inefficient earth-bound primitives into wandering tribes of buffalo hunters, mobile and dangerous to the growing white pressures.

Meanwhile, some two thousand miles to the east of Kino's land, other herds of Spanish-Barb horses were stolen from other missions and eventually found themselves in the hands of the native Indians of Georgia and the Carolinas. Shortly these mustangs met another kind of horse that had been brought by white men in ships to the English settlements.

And thus it was that the first great crossing of horse breeds and types took place in America: the native-born Indian-Spanish-Barb and the English horse. The result was a type of pure American horse that lives on to this day.

Frazier Hunt and Robert Hunt

Father Kino's Mustangs

Excerpt from the book "Horses and Heroes"

"Discover The Horse That Discovered America"

The Critically Endangered

Colonial Spanish Mission Horse

Deb Wolfe

The pure Spanish horses transported to New Spain demonstrated their steady mind and hardiness long before they reached the beaches of eastern Mexico. Horses travelled to the Americas suspended from rafters below deck, supported by huge slings around their bellies to prevent them from breaking their legs. Those that survived this arduous voyage multiplied and thrived in the New World.

Father Kino’s Mission Horses

As early as 1700, Father Eusebio Kino began leaving bands of 20 to 30 of his Spanish “mission horses” at each small settlement that he founded or visited throughout the Pimería Alta (present-day Arizona and Sonora, Mexico). Using Spanish horses he obtained from missions to the south, Kino’s breeding ranch at Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in Sonora produced a horse that could carry a rider over 60 miles of rough terrain in a single day. Kino’s horses quickly adapted to the temperature extremes and punishing

terrain and could survive by feeding on the sparse vegetation of the arid Sonoran Desert.

Direct descendants of Kino’s mission horses were widespread by 1775, and Sonoran-born Juan Bautista de Anza likely grew up riding them. They would have been the same type of sturdy mount he would rely upon for his expeditions to Alta California. Records indicate that his soldiers, friars, and settlers rode on horses supplied from the Tubac area (140 Spanish horses in 1774, and 500 in 1775).

Until the 1850s, the pure Colonial Spanish horse that dominated the West remained in large numbers, largely unchanged. Tragically, by the 1950s, after a century of systematic slaughter of Indian ponies and range horses by the U.S. Government on public lands, by ranchers on private lands, and by deliberate cross-breeding with European stock, only 1,500 true Colonial Spanish horses could be found.

A Remarkable Discovery

In 1987 – 300 years after Kino founded his horse ranch – an isolated herd of 120 Colonial Spanish “mission-type” horses was discovered 50 miles west of Tubac, Ariz., on an isolated ranch. The Wilbur-Cruce family owned a territorial ranch that in 1885, purchased 25 mares and a stallion from Juan Sepulveda, a horse trader from Sonora. Importantly, the Wilbur-Cruce ranch horses were kept as a closed herd.

Equine geneticist Dr. D. Phillip Sponenberg found Iberian DNA markers among the Wilbur-Cruce horses. “The Cruce horses are one of a handful of strains of horses derived from Spanish Colonial days that persist as purely (or as nearly as can be determined) Spanish to the present day,” he concluded. “They are the only domesticated ‘rancher’ strain of horses that persists in the Southwest.”

Dr. Sponenberg then examined the horses and reported, “The horses are remarkably uniform, and of a very pronounced Spanish phenotype. In some instances this is an extremely Spanish type, such as is rare in other Spanish strains persisting in North America”. Following confirmation that the herd was indeed Spanish, the herd was divided among five private ranches for conservation.

The Critically Endangered Kino Mission Horse Today

Despite volunteers’ best efforts to expand their numbers, the Wilbur-Cruce mission horse remains “critically endangered”. A 2011 American Livestock Breed Conservancy census of Wilbur-Cruce horses lists approximately 92 remaining. Today, breed stewards, new horse-owners and volunteers are urgently needed to ensure that the bloodlines of these horses endure for future generations to enjoy.

They are a living treasure.

Deb Wolfe

The Critically Endangered - Colonial Spanish Mission Horse

Noticias de Anza No. 52 July 2012

http://www.nps.gov/juba/parknews/upload/Noticias-52-July-2012-2.pdf

Author Deb Wolfe is a preservation breeder of the Colonial Spanish Horse.

For more information on the Wilbur-Cruce “Mission” Horse, contact Deb Wolfe at 408-504-4438 or visit www.SpanishBarb.com. Read more about Colonial Spanish horses at the American Livestock Breed Conservancy website: www.ALBC-usa.org

Historical Background Of

The Wilbur Ranch Horses (Wilbur-Cruce Horses)

Jane Dobrott

The Rueben Wilbur strain of Colonial Spanish Horse, (also known as Spanish Barb, and Spanish Mustang), has a unique historic and genetic background. All such strains of Spanish horse can trace their origin to the royal breeding farms set up in the Caribbean Islands by the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella. After horse populations were increased, they were then exported to mainland Mexico where the Conquistadores, the missionary fathers and the native Indians took part in moving them northward into what is now the United States.

In the late 1600's, Father Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest and missionary, first brought the Spanish horse into the Pimeria Alta, the area made up of southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Father Kino established his headquarters in the San Miguel river valley, approximately twenty-five miles east of today's Magdelena, where he founded Mission Dolores and Rancho Dolores. It is from this area that the Wilbur horses originated. His mission remained active in the production of livestock for many decades, producing stock that was destined to be spread northward as each new mission was established. He was responsible for mapping vast areas of previously unknown territory, setting up missions, churches, schools and settlements, seeing to it that each was liberally stocked with animals.

The Spanish horse played an important role in the early development of North America. During the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish horse was the most common equine, existing in an arc from the Carolinas, down to Florida, across the southern part of the county and throughout the western mountains and plains. Beginning in the 19th century, the Spanish horse became rare as it was replaced by larger horse types brought by pioneers from the Northeast. Herds held by Native Americans were all but exterminated in the latter years of Indian domination. A few herds remained in isolation, but for the most part, the fate of the Spanish horse was in the hands of a few individuals, families, and Native Americans who recognized their value and sought to preserve them.

In 1867, Rueben Augustine Wilbur, a Harvard educated physician, who originally came to Southern Arizona to become the Cerro Colorado Mining Company physician, homesteaded the first cattle ranch in the Arivaca district of the "Pimeria Alta". In 1870, Dr. Wilbur became the Indian agent to the Pima and Maricopas and in 1871 to the Papagos, establishing San Xavier reservation at the age of thirty-one. In the late 1870's, he obtained a "manada" of twenty-five mares and one stallion from a horse trader named Juan Sepulveda, who brought them from Father Kino's historic home place, Rancho Dolores. Sepulveda moved a large herd from Rancho Dolores north across the border, passing by the Wilbur ranch on his way to the Kansas City stockyards.

Augstine A. Wilbur, son of Dr. Wilbur, was born on the ranch, and eventually took over its management. In 1933, when Augustine was killed in a fall from his horse at the age of fifty-six, his eldest daughter, Eva Wilbur, was called upon to oversee the ranch. Through three successive generations spanning over 110 years, their Spanish horses were kept in isolation on the ranch. Only those horses selected for ranch work were caught and handled. The others were allowed to run in wild bands in rocky and mountainous terrain, developing a ruggedness and intelligence that only the harsh selection process of survival of the fittest can produce.

Preservation of a Living Artifact

When the Wilbur ranch was sold in 1990, Mrs. Wilbur-Cruce donated the herd of seventy-seven wild horses to The American Minor Breeds Conservancy (now called "The Livestock Conservancy), an organization dedicated to conserving endangered breeds of livestock unique to this continent. The Conservancy coordinated the task of trapping and removing the horses, ensuring that blood samples were taken for typing.

Blood typing is a test for genetically inherited characteristics that can be detected in the blood. A basis for comparison is formed by looking at characteristics of all types of Iberian Peninsula horses (those descended from a common source in Colonial Spain). Because Spanish breeds are different in type from other breeds, they can be recognized in this way. Dr. Gus Cothran, director of the Equine Blood Typing Research Laboratory at the University of Kentucky, concluded that the Wilbur horses were "a cohesive group based on type with nice genetic variability, in other words, no inbreeding. The most significant finding was that the results provided evidence of Spanish ancestry supportive of their oral history."

Unique Genetic Resource

"The Wilbur-Cruce horses are one of a very small handful of horse strains derived from Spanish Colonial times that persist to the present day in as pure a state as can be determined. They are the only known "rancher" strain of pure Spanish horses that remain in the Southwest. The Wilbur-Cruce horses are of great interest because they are a non-feral strain. The only other strains of Spanish horses that still persist are feral strains in certain isolated areas. Some pure examples, which are otherwise extinct or contaminated, are in privately owned and managed herds. The Wilbur-Cruce horses, as a non-feral strain are truly unique ... "

"Visual examination of the herd indicates that their history is very likely accurate. The horses are remarkably uniform and of a very pronounced Spanish phenotype. In some instances this is in the extreme, such as is rarely seen to persist in North America in other Spanish strains."

"The need to conserve this herd is great, since they represent a unique genetic resource. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has limited their interest in rare breed conservation to those breeds that have no Arabian or Thoroughbred influence, because of the incredible scarcity of such populations worldwide. The Wilbur-Cruce horses fit in this category very securely and are therefore of great interest and importance not only in North America, but also in the worldwide efforts to conserve genetically unique populations of livestock".

"The Wilbur-Cruce population is a most significant discovery of a type of horse largely thought to be gone forever," according to Dr. Phil Sponenberg, D.V.M.

Jane Dobrott

The Historical Background of The Wilbur Ranch Horses (Wilbur-Cruce Horses)

Spanish Barb Journal 1994

Selected References

Colonial Spanish Horses, Phil Sponenberg, D.V.M.

The Spanish Horse in the New World, Marye Ann Thompson.

Evaluation of the Wilbur-Cruce Herd of Horses, Phil Sponenberg, Associate Professor, Pathology and Genetics, Technical Panel Chair,

American Minor Breeds Conservancy, Virginia Maryland Regional college of Veterinary Medicine VPI & SU.

Biographical sketch, Pioneer Historical Society, Tucson, AZ

Personal interview, Eva Antonia Wilbur-Cruce by Jane Dobrott

Person Communication, E. Gus Cothran, PhD. University of Kentucky, Director, Equine Blood Typing Research Center by Jane Dobrott.

Final Research Report To U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Solicitation No. AA 852-RP-27, Contract No. AA852-CT5-28. "Wild Horse Parentage and Population Genetics". N.T. Boling, Robert W. Touchberry, University of California at Davis, January 15, 1988.

The Spring Corrida

Eva Antonia Wilbur-Cruce

"They were brought here from Rancho Dolores in Mexico, the headquarters of Father Kino, who had brought them from Spain - a fine breed of Barbs that were brought to Spain by the Moors.

Grandfather Wilbur brought fine Morgan horses from Colorado, but they didn't survive. The Spanish horses thrived in the desert and were the horses of the day. They were our companions from sun up to sun down and sometimes deep into the night, year in and year out. They had speed, stamina, and intelligence, and, strange as it may seem, they had feelings. I have seen them die heartbroken. In all the sixty years that I spent in the saddle off and on, only once did my horse play out on me, and that was due to my own hard riding.

Riding twenty miles away from any habitation, approximately seven hours away from any help, usually made me nervous and tense, and this put my horse on the alert, so I watched him closely for any signal. I knew if danger were near he would tell me. Years of close association had taught me his language.

The Spanish horse was made to build the West, and that he did.

And so the Spanish horses were made for the country and were much like the country itself, rugged and beautiful. They carried themselves well and carried their riders with utmost care, placing their small feet on solid ground and balancing themselves as they reached out for better footing.

It was amusing to see an 800-pound horse under a 200-pound man with an enormous saddle and a 1000-pound bull at the end of a rope. They knew the danger they were under, but they worked with their riders with courage and outstanding intelligence. And none more beautiful! These were the horses that went to that spring corrida."

Eva Antonia Wilbur-Cruce

"A Beautiful, Cruel Country"

The University of Arizona Press - 1987

Pages 107-108

How to Recognize Kino Horse Like Characteristics

Names

The modern day strains of Kino's horses have many names: Padre Kino's Mission Horse, Spanish Barb, Spanish Colonial Horse and the Sonoran Desert horse. They are also called by regional strain names: Wilbur-Cruce (Arizona), Santa Cruz Island, Marsh Tacky, Florida Cracker, Choctaw and Banker.The Native Americans called them Dog Horses because of their intelligence and ability to bond to people. Also they are called Rock Ponies because of their endurance off trails.

Size and Shape

The Kino horse stands from 13.2 to 15 hands at the withers and weigh between 700 - 900 pounds. They are short coupled and deep bodied, but narrow from the front so that the front legs join the chest in the shape of an "A". The tail is set low. They have distinctively broad foreheads and narrow lower faces with crescent shaped nostrils.

The Kino Horse has made substantial genetic contributions to the American gaited breeds including the Tennessee-Walking horse, American Quarter Horse, Morgan, and other stock horse breeds.

Coat of Many Colors

Virtually every coat color can be found. Their genetics are the source for the Pinto, Appaloosa and Palomino colors.

Personality

They are renowned for their intelligence, even temperament and gentle dispositions.

Contributions to Other Breeds

The Kino horse has also made substantial genetic contributions to the American gaited breeds including the Tennessee-Walking horse, and to the American Quarter Horse, Morgan, and other stock horse breeds.

The Spanish Barb

Richard Collins

The horse gave the cowboy his exalted status. As America spread westward in search of its Manifest Destiny, the early explorers ran into vast herds of feral horses, especially on the Southern Great Plains, estimated by historian Dan Flores to number one to two million head. These horses had escaped from the Spanish settlers or Native Americans to breed and multiply on the same fertile grasslands that supported twenty-five million bison. A lively trade sprang up with Native Americans and Anglo-Mexican horsemen capturing wild herds to sell to farmers, ranchers, wagoneers, and the military.

These horses carried the bloodlines of the Spanish Barb brought to the Mexican mainland by Spanish soldiers in the early 1500s. A compliant, loyal breed with tremendous stamina, the Spanish Barb was a cross between the Moorish horses of North Africa and the native Spanish Jennet. Compact and wide-bodied in conformation, with long mane, tail, and forelock, the Barb had a crested neck, large ears, and small-boned legs. Hernan Cortes landed near Veracruz, Mexico in 1519 with sixteen of these horses and conquered the entire Aztec Empire in a matter of weeks. One soldier wrote that "Next to God, they [the horses] protected us the most." The conquistadors favored the coyote-colored dun horses trimmed in black.

R. B. Cunninghame-Graham, born a Scottish laird in 1852, immigrated to Argentina in the 1870s and became a horseman, bronc rider, cowboy, cattle rancher, buffalo hunter, and soldier. Returning home in his declining years, he became a writer of renown and member of the British Parliament. Cunninghame-Graham eulogized the Spanish Barb in the books "Horses of the Conquest" and "Rodeo." Two horses with similar bloodlines carried his friend, A. F. Tschiffely, on a three-year journey from Argentina to New York, 1925 to 1928. (See Tschiffely's Ride,1933).

One Christmas when our cows were tucked safely away on the mountain, Diane and I escaped to Chile where the Spanish conquistadors had left behind a pure strain of the Spanish Barb. We rode a pair of geldings, bay and grulla-colored, into the Andes Mountains in search of the condor, the world's largest vulture. The horses carried us for miles through the heavy bog of temperate rain forest, crossing glacial-fed rivers belly deep, never missing a step as we climbed into the mountain strongholds. We did not see the bird, but the horses left an indelible imprint on me as a sure-footed, completely reliable breed.

Richard Collins

Cowboy is a Verb: Notes From A Modern-Day Rancher

2019

John C. Van Dyke and His Spanish Barb

The desert-bred pony wandered free at night and ate grass which he found in clumps here and there, especially in the mountains. He grazed far afield, but returned to the camp several times each night to make sure Van Dyke and the dog were still there. Once he returned at a gallop in the middle of the night, chased by three gray wolves. When there was no grass he learned to eat the joints of cholla cactus from which Van Dyke had removed the spines.

Richard Shelton

Introduction 1980

"The Desert"

John C. Van Dyke 1901

The Spanish Barb in Europe

"Without a doubt, the Spanish Horse is the best horse in the world for equitation, not only because of his shape, which is very beautiful, but also because of his disposition, vigorous and docile, such that everything he is taught with intelligence and patient he understands and executes perfectly."

Baron d' Eisenberg

L' Art de Monter à Cheval 1759