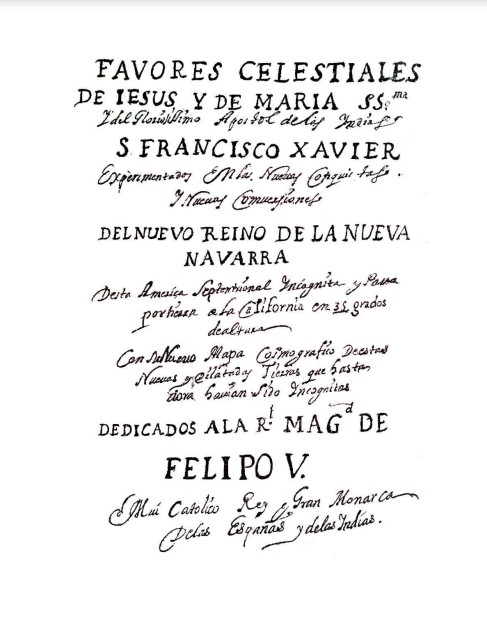

Favores Celestiales

Introduction

Herbert E. Bolton

Favores Celestiales

Introduction

Herbert E. Bolton

The problem of the biographer of Father Kino will be to tell much in little, so many and long continued were his activities. He was great not only as missionary and church builder, but also as explorer and ranchman. By Kino or directly under his supervision missions were founded on both sides of the Sonora-Arizona boundary, on the Magdalena, Altar, Sonoita, and Santa Cruz Rivers. The occupation of California by the Jesuits was the direct result of Kino's former residence there and of his persistent efforts in its behalf, for it was from Kino that Salvatierra, founder of the permanent California missions, got his inspiration for that work.

To Kino is due the credit for first traversing in detail and accurately mapping the whole of Pimeria Alta, the name then applied to southern Arizona and northern Sonora. Considered quantitatively alone, his work of exploration was astounding. During his twenty-four years of residence at the mission of Dolores, between 1687 and 1711, he made more than fifty journeys inland, an average of more than two per year. These journeys varied from a hundred to nearly a thousand miles in length. They were all made either on foot or on horseback, chiefly the latter. In the course of them he crossed and recrossed repeatedly and at varying angles all of the two hundred miles of country between the Magdalena and the Gila and the two hundred and fifty miles between the San Pedro and the Colorado. When he first opened them nearly all his trails were either absolutely untrod by civilized man or had been altogether forgotten. They were made through countries inhabited by unknown tribes who might but fortunately did not offer him personal violence, though they sometimes proved too threatening for the nerve of his companions. One of his routes was over a forbidding, waterless waste, which has since become the graveyard of scores of travelers who have died of thirst because they lacked Father Kino's pioneering skill. I refer to the Camino del Diablo, or Devil's Highway, from Sonoita to the Gila. In the prosecution of these journeys Kino's energy and hardihood were almost beyond belief.

All the foregoing was the work of a man of action, and it was worthy work well done. But Kino also found time to write. Historians have long known and had access to a diary, three "relations," two or three letters, and a famous map, all by Kino, and all important for the history of the region where he worked. His map published in 1705 was the first of Pimeria based on actual exploration, and for nearly a century and a half was the principal map of the region in existence. And there has now come to light, discovered by the present writer in the archives of Mexico, this vastly more important work a complete history, written by Kino himself at his little mission of Dolores, covering nearly his whole career in America. It was known to and used by the early Jesuit historians, but has lain forgotten ever since. It is now found to be the source of practically all that has been known of the work of Kino and his companions, and to contain much that never has been known before. Kino, therefore, was not only the first great missionary, ranchman, explorer, and geographer of Pimeria Alta, but his book was the first and will be for all time the principal history of his region during his quarter century.

Early Days in Europe

Priest and Professor

Only with extreme difficulty can we of the twentieth century comprehend the spirit which inspired the first pioneers of the Southwest. We can understand why man should struggle to conquer the wilderness for the wealth which it will yield, but almost incomprehensible to most of us is the sixteenth century ideal which brought to this region its first agents of civilization the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries. These men came single minded, imbued with zeal for the saving of souls. Most of them were men of liberal education. Many of them were of prominent families, and might have occupied positions of honor and distinction in Europe.

Peer of any of these noble spirited men was Father Kino, Apostle to the Pimas. Eusebio Francisco Kino, as he wrote his name, was born in the Valley of Nonsburg, near Trent, in the Austrian Province of Tyrol, on August 10, 1644. It is an interesting coincidence that his birth was in the same year that his intimate friend, disciple, and fellow worker, Juan Maria Salvatierra, was born at Milan. It has generally been assumed that Kino's name was originally Kuhn, but German scholars themselves claim otherwise. Sommervogel, whose Bibliotheque has the nature of an official publication, asserts that the name was Chino, as was affirmed to Father Melandri in 1870 by a member of the Chino family. This view is borne out by several contemporary letters published in German in Stocklein's Neue Welt-Bott, where the name is given as Chinus and Chino. While in New Spain the Jesuit himself usually wrote his name Kino, and Spaniards sometimes spelled it Quino, to preserve the hard sound of the ch, no doubt.

In point of nationality Kino is typical of a large class of the early Jesuit missionaries in Arizona, Sonora, and California. That is, although he was in the service of Spain, he was non-Spanish by blood and breeding. Among Kino's companions and successors, for example, we find Steiger, Keler, Sedelmayr, and Grashofer, whose names disclose their German origin; Goñi, Salvatierra, Picolo, and Ripaldini, bearing in their names the marks of their Italian extraction; and Januske and Lostinski, whose surnames stamp them as Bohemians.

Though his name was Italian in form. Kino's birth, education, and early associations were altogether German. His early education was acquired at Ala, in Tyrol, and later he studied in the universities of Ingolstadt and Freiburg. One of his teachers at the latter place whose instruction was long remembered and treasured was Father Adam Aygentler, author of a world map. Another of his instructors was Father Henry Scherer, author of the "Hierarchical Geography" published at Munich in 1703, in which some of Kino's writings on California were incorporated.

The primary facts of Kino's entry into the Company of Jesus are set forth in the following extract from the original manuscript Libra de Profesiones of the Province of Mexico: "Native of Trent, born August 10, 1644; entered the Company in the Novitiate of Lansperga [Landsberg], of the Province of Upper Germany, Nov. 20, 1665; he made his vows; he finished his studies, made his third probation, and has taught grammar three years."

Had he chosen to do so Kino might have enjoyed an honorable position, and perhaps even won fame in Europe, for during his student career at Freiburg and Ingolstadt he greatly distinguished himself in mathematics. In 1676, when the Duke of Bavaria and his father, the Elector, went from the electoral court at Munich to Ingolstadt, they engaged Kino in a discussion of mathematical sciences, with the result that he was offered a professorship in the University of Ingolstadt. But he preferred to become a missionary to heathen lands. To this, perhaps, he was inclined by family tradition, for he was a relative of Father Martini, famous missionary in the East and author of many works on China.

The decision to become a missionary was made when Kino was twenty-five, as the result of a serious illness. In his Favores Celestiales he tells us that "To the most glorious and most pious thaumaturgus and Apostle of the Indies, San Francisco Xavier, we all owe very much. I owe him first my life, which I was caused to despair of by the physicians in the city of Hala, of Tirol, in the year 1669; second, my entry into the Company of Jesus; and third, my coming to these missions." Another mark of Kino's gratitude for his recovery was the addition of Francisco to his name..

Journey to the New World

Vow Fulfilled and Interlude in Spain

He had hoped to go to the Far East, literally to follow in the footsteps of his patron, but in 1678 there came a call for missionaries in New Spain, and thither he was sent instead. The exact date of Kino's arrival in Mexico has been a subject of conjecture and even of error by secondary writers, 1678, 1680, and 1681 being variously given. It will be seen below that the last date is the correct one.

The circumstances of Kino's journey to America can be gleaned from Stocklein's Neue Welt-Bott, a valuable but a much neglected source for American history. In that work is published a letter to his father by Adam Gerstle, a Jesuit missionary who came to the New World in the same mission with Father Kino. From Sommervogel we learn that Kino set out for America in April, 1678. From Father Gerstle's letter we learn that he and eighteen others, including Father Kino, left Genoa on June 1 2, on two Genoese vessels. The band included Father Carolus Calvanese and Franciscus Borgia, Italians; Theophilus de Angelis, a Welshman; Andreas Mancker, Carolus Borango, and Adam Gerstle, Austrians; Joannes Tilpe, Joannes Strobach, Josephus Neuman, Mathias Cuculinus, Paulus Klein, Wenceslaus Christman, and Brother Simon Poruhradiski, Bohemians; Joannes Ratkay, Hungarian; Thomas Revell, Netherlander; Mathias Fischer (country not named); Antonius Kerschbaumer and Eusebius Franciscus Chinus, Tyrolese.

The vessels reached Alicante on the twenty-fifth of June. Early in the voyage they had experienced a heavy storm, and when near port were becalmed for several days. On the way they passed numerous vessels, and as each hove in sight they prepared to give it battle, but all proved to be friendly. From Alicante the companions went to Seville, which they reached too late to take passage in the fleet sailing to the West Indies.

Father Gerstle's letter gives a very graphic account of some phases of Seville life. He was especially interested in the monopoly of industry and commerce by the Dutch and the French, of the latter of whom forty thousand lived in Seville; in the amazing number of clergy and monastic houses there; in the prevalence of poverty and the multitude of beggars, of whom the archbishop regularly fed twenty-two thousand out of his income; in the crude skill of the blood-letters, at whose hands one of the nineteen, Father Fischer, succumbed; in the depreciation of silver on the arrival of a treasure fleet from America; in the crude methods of public execution, and the premature burials; and in the bull fights, in which the nobles participated and on which the Church frowned.

The delay in Spain was unexpectedly long. In 1679 some royal ships sailed for America, but as they went by the African coast to get slaves the Jesuits did not embark. Some private vessels also sailed, but their charge for the passage was higher than the Father Procurator was willing to pay, consequently they awaited the departure of the next royal fleet for the West Indies.

Late in March (the twenty-fifth) Gerstle and his companions returned to Cadiz, and on the eleventh of July the West Indian fleet sailed, convoyed by two armed galleons. But the vessel on which the eighteen Jesuits embarked foundered on a rock shortly after sailing, and they returned the same night to Cadiz on a small boat, the Tartana. The Father Procurator now bent every energy to get passage on one of the other vessels, and hurried back and forth between the port authorities and the admiral of the fleet. About two o'clock the next morning the sleeping band of Jesuits, now increased by two or three, were awakened by the Procurator, put on board a boat, and taken to the fleet, already outside the harbor. The first vessel overhauled consented to take Fathers Calvanese and Borgia; the second refused to take any; on the third embarked Fathers Tilpe and Mancker; on the fourth Father Borango and Father Zarzola, superior of the mission; on the fifth Fathers De Angelis and Ratkay; on the sixth Fathers Strobach and Neuman. Brother Poruhradiski, who had remained on the wrecked vessel with the Jesuits' baggage, also managed to find passage on the same ship with the superior. But twelve were left behind, among them being Fathers Cuculinus, Klein, Christman, Kerschbaumer, Chinus (Kino), Revell, and Gerstle. It is this enumeration by Father Gerstle that gives us our clue to Father Kino's movements.

Father Gerstle and seven companions now returned to Seville to wait, and to minister during an epidemic. Father Kino evidently remained at Cadiz, where he observed the great comet which was visible there between December and February. Meanwhile the Father Procurator conducted a lawsuit to recover six thousand dollars paid in advance for passage in the wrecked vessel.

On January 16, 1682, Father Gerstle and his companions again left Seville for Cadiz, arriving on the eighteenth, and on the twenty-ninth they at last set sail for America. In the West Indies the fleet divided, according to custom, and eight of the eighteen companions went to New Granada, the rest continuing to Vera Cruz, which they reached after a rough voyage of over ninety days.

The above account is gleaned from the letter written by Father Gerstle at Puebla, on July 14, 1681. It confirms Father Ortega's statement that Kino arrived in America in 1681, Sommervogel and others to the contrary, notwithstanding. It, in turn, is circumstantially confirmed by the entry in the manuscript Libro de Profesiones of the Province of Mexico, which says of Fathers Kino and Revell : "They came from the Province of Austria and arrived at Veracruz on May 3, 1681."

The band of devoted Jesuits who had set out from Genoa together were destined to scatter to the ends of the earth. The story of their personal experiences in America and the islands of the western seas occupies large space in the pages of Stocklein's Neue Welt-Bott. As has been stated, eight of the companions were sent to New Granada. Ten came to Mexico, whence some went to the Philippines and others to the Marianas Islands and to China. Fathers Borango, Tilpe, Strobach, De Angelis, and Cuculinus went to work among the heathen of the Marianas Islands, Father Tilpe still being there in 1703. Mancker and Klein went to the Philippines and Gerstle to China. Ratkay worked in Sonora, Neuman in Nueva Vizcaya, Kino in California, Sonora, and Arizona. Of the four who went to Marianas Islands, three - Borango, Strobach, and De Angelis -won the martyr's crown.

First Entrada

Baja California

Father Kino's mathematical knowledge brought him into prominence as soon as he arrived in Mexico, where he at once entered into a public discussion with the famous Jesuit scholar Sigüenza y Gongora, concerning the recent comet. One of the fruits of this discussion was a pamphlet published by Kino in Mexico in 1681 under the title: "Astronomical explanation of the comet which was seen all over the world during the months of November and December, 1680, and in January and February in this year of 1681, and which was observed in the city of Cadiz by Father Francisco Kino, of the Company of Jesus."

As a result of this debate Kino enjoyed the friendship of Sigüenza y Gongora. This was no small matter, for Sigüenza was a man of great intellect and of wide influence. The impression made by Father Kino on Sigüenza was shared by the viceroy, the Marques de la Laguna, and this in time led to further recognition.

Father Kino's first important missionary work in America was in Lower California. For two centuries and a half the Spaniards had made weak attempts to subdue and colonize that forbidding land. California had been discovered by one of Cortes's sailors in 1533. Two years later the great conquistador himself led a colony to the Peninsula, then thought to be an island and called Santa Cruz. The enterprise failed, but Cortes continued his explorations, and Ulloa, sent out by him in 1539, rounded the cape and proved Santa Cruz to be a peninsula. Henceforth it was called California. Three years later Cabrillo, in quest of the Strait of Anian, that is, the northern passage to the Atlantic in which everybody believed, explored the outer coast of California beyond Cape Mendocino.

New interest in California followed the conquest of the Philippines by Legazpi (1565-1571); indeed, in the later sixteenth century California was as much an appendage of Manila as of Mexico. Legazpi's men discovered a practicable return route to America, down the California coast, and thereupon trade, conducted in the Manila galleon, was established between Manila and Acapulco. But the voyage was long, scurvy exacted heavy tribute of crews and passengers, and a port of call was sorely needed. English pirates, too, like Drake and Cavendish, infested the Pacific, and were followed by the Dutch Pichilingues. California, therefore, must be explored, protected, and peopled.

It was with these needs in view that Cermeno in 1595 made his disastrous voyage down the California coast; that Vizcaino in 1597 attempted the settlement of La Paz, and in 1602 explored the outer coast; and that the king in 1606 ordered a settlement made at Monterey.

The Monterey project failed, but settlements and missions crept up the Sinaloa coast across the Gulf, and the pearl fisheries of California attracted attention, hence new attempts were made on the Peninsula. Having little cash to spare, the monarchs tried to make pearl fishing rights pay the cost of settlement and defense. In the course of the seventeenth century, therefore, numerous contracts were made with private adventurers. By the terms the patentees agreed to people California in return for a monopoly of pearl gathering. With nearly every expedition went missionaries, to convert and help tame the heathen. In pursuance of these agreements several attempts were made to settle, especially at La Paz, where Cortes and Vizcaino both had failed. Other expeditions were fitted out at royal expense. The names of Carbonel, Cordova, Ortega, Porter y Casanate, Pinadero, and Lucenilla all stand for seventeenth century failures to colonize California.

At first the natives of California had been docile, but they had been enslaved and abused by the pearl hunters, against the royal will, and had become suspicious and hostile, as later pioneers learned. Through various misunderstandings and incomplete explorations, in the course of the century California had again come to be regarded as an island.

In spite of the repeated failures, another attempt at settlement was decided upon. By an agreement of December, 1678, confirmed by a royal cedula of December 29, 1679, the enterprise was entrusted to Don Isidro Atondo y Antillon, governor of Sinaloa, who was now given the title of Admiral of the kingdom of the Californias. The spiritual ministry, so important a part of every Spanish conquest, was assigned to the Jesuits, by agreement with the Father Provincial, Bernardo Pardo.

In the midst of Atondo's preparations Father Kino arrived in Mexico (in May, 1681), and was named, with Father Matias Goñi, missionary to California. Again Kino's mathematical learning was given recognition, for the viceroy made him royal cosmographer, that is, astronomer, surveyor, and map maker, of the expedition. Before leaving Mexico Kino prepared himself for his scientific task by studying California geography, borrowing maps for the purpose from the viceroy's palace and taking them to the Colegio Maximo of San Pedro y San Pablo to copy.

It was expected that the expedition would sail in the fall of 1681, and before the end of the year Kino left the capital for his new field of labor. On November 15, presumably on his way through Guadalajara, he was made vicar of the Bishop of Nueva Galicia for California, Father Goñi being made his assistant. As the vessels for the expedition were being built by Atondo at Pueblo de Nio, near Villa de Sinaloa, thither Kino made his way, and there we find him in March, 1682.

At last, on January 17, 1683, the expedition sailed. The voyage was difficult, the crew raw, and the vessels were driven into the harbor at Mazatlan. Two months after setting sail they entered the Sinaloa River, well north of their objective point. From here they retraced their course, crossed the Gulf, and reached the coast near La Paz, already the site of so many failures. During the voyage the launch was lost and never reached port.

On April 1 anchor was cast and a formal proclamation issued requiring good treatment of the Indians and regulating the gathering of precious metals and pearls, the two primary interests of the expedition. Next day a site was selected and a cross erected near a fine grove of palm trees and a good spring of water. On the fifth all disembarked with the royal standard, a salute was fired, three vivas were shouted for Charles II, and the admiral took possession for the king, calling the province Santisima Trinidad de la California. At the same time Fathers Kino and Goñi took ecclesiastical possession.

A small fort was begun at once, and a log church and huts were erected. Sending the Concepcion to the Rio Yaqui for supplies, Atondo and Kino made minor explorations. The Indians near the settlement, though shy at first, soon became friendly, and Fathers Kino and Goñi began to study their language. The Guaycuros, toward the south, and enemies of the former, were hostile on the other hand, and by July 1 a state of war existed. The soldiers were now panic stricken, and clamored to abandon the settlement. "It is plain," says Father Venegas, that Atondo "had with him few like those courageous and hardened men who at an earlier day had subdued America." Since the Concepcion had not returned, and supplies were consequently short, Atondo yielded, and on July 14 the San Jose weighed anchor, with all the Spaniards on board.

Second Entrada

Baja California

Atondo now went to the Sinaloa coast to refit, in order to make a new attempt farther up the California coast, where more promising lands and Indians had been reported. Setting sail again, on October 6 he landed with the missionaries and men at a bay called San Bruno, a few leagues north of La Paz. Here a new settlement was begun, the San Jose being sent for supplies and recruits and with dispatches for the viceroy.

The routine of life at San Bruno from December 21, 1683, to May 8, 1684, can be gleaned from the detailed diary kept by Father Kino and preserved to us in the original in the archives of Mexico. It begins with an account of an exploration by Father Kino and Ensign Contreras into the Sierra Giganta, to the west. The principal occupations at the little outpost of civilization were those connected with providing food, shelter, protection, and the conversion of the natives. The docile Indians labored willingly in building the fort, the houses, and the church, and brought such supplies as the sterile land afforded.

Father Kino's diary gives us a perfect picture of a true missionary, devoted heart and soul to the one object of converting and civilizing the natives, and for whom no task was too mean and no incident too trivial if it contributed to his main end. He was like the artist, or the true scholar, much of whose labor would be unbearable drudgery to one not inspired with the zeal of a devotee.

Kino regarded the poor natives as his personal wards. He loved them with a real affection, and he ever stood ready to minister to their bodily wants, or to defend them against false charges or harsh treatment. He dwelt with affection on all evidence of friendship shown by the Indians, and recorded every indication of their intelligence. He took sincere delight in instructing them, and in satisfying their childish curiosity regarding such things as the compass, the sun dial, the lens with which he started fires, and the meaning of the symbols used in his maps.

The first task of the missionary was to win the confidence of the natives, and the direct way to their hearts was through their stomachs. Whenever a visit was made to an outlying rancheria, therefore, gifts of maize, pinole, and other eatables were carried for all natives who might be encountered. When strangers came from a distance they, too, were given presents. Confidence having been secured, the Indians would leave their boys with the missionaries, whose house was usually crowded with them over night. Thus was afforded a means of teaching them the Spanish language, and the rudimentary uses of clothing, and to recite the prayers, sing, and perform domestic duties. It was with the young that Kino was especially concerned, and whenever he made an excursion he was usually followed by a troop of Indian boys running by his side, trying to keep up, or crying if left behind. Often one or more urchins might be seen triumphantly mounted behind the Father on the haunches of his horse. Kino tells with zest how a young boy who was living at the mission resisted the efforts of his parents to take him away, calling for help on "Padre Eusebio."

Nothing gave Father Kino such true pleasure as some sign that an Indian was becoming interested in the Faith. He dwells at length and with evident delight on the story of a little native girl who knelt before a picture of the Virgin and begged permission to hold the Christ Child; on the progress made by his charges in repeating the prayers, singing the salve, and reciting the litanies; and on their zeal in helping to decorate the crude church for the celebration of the feast days.

Sometimes, as was true of all missionaries among the heathen, his ingenuity was put to the test to explain Christian concepts in the simple Indian language. A classic example is his own story of how he explained the Resurrection by reviving some apparently lifeless flies. When the astonished Indians shouted "Ibimu huegite" they had given the Father the native term for which he had been seeking.

On August 10 the San Jose at last returned, bringing twenty additional soldiers, supplies, and dispatches from the viceroy. At this time Father Juan Bautista Copart also came, and on August 15 Father Kino made final profession within the Jesuit Order in Father Copart's hands. An extended exploration across the mountains was now projected, and during the autumn the San Jose plied to and from the Yaqui River, bringing horses, mules, and supplies. On the first expedition, made between August 29 and September 25, Father Kino accompanied Captain Andres, and secured aid from the mainland missions, particularly from Father Cervantes at Torin. Bancroft conjectures that Kino "probably remained in Sonora a year," but such was by no means the case. On a subsequent trip Kino's place was taken by Father Goñi. While the San Jose was making her supply voyages a new post and mission were established a few leagues inland from San Bruno at the fine springs of San Isidro.

The expedition over the mountains was planned for December, but when it was ready to start some of the soldiers opposed it. The year had been one of extreme drought, both in California and on the mainland, and there was a serious lack of supplies. Both the Concepcion and the launch had failed to appear, and the safety of the settlers depended on one small vessel, which was now about to leave for Mexico. The clamors of the faint-hearted, however, merely served to bring out that optimism which was one of Kino's strongest qualities, and in his letters to the viceroy he discounts the dismal prophesies of the malcontents.

The San Jose sailed on December 14, bearing Father Copart, whose stay in California was therefore short, and on that day Atondo was at San Isidro ready to start on his expedition on the morrow, accompanied by Father Kino, twenty-nine soldiers and Indian guides, and taking eighty mules and horses. This expedition apparently did not succeed, but either it or another did, for Father Kino tells us that in 1685 he, with Atondo, crossed the mountains to the South Sea, in latitude twenty-six degrees, where he saw certain blue shells, which fifteen years later became an important factor in his further movements. Meanwhile the complaints of the soldiers grew stronger, and the tide of discontent could not be stemmed even by Father Kino's optimism. A council was held, and on May 7 Atondo, his men, and the missionaries again abandoned their settlement.

For the remainder of the story of this enterprise we have hitherto been dependent chiefly upon Father Venegas's history, but we now have access to a file of contemporary letters by Fathers Kino and Goñi which give us more exact information. On May 8 Atondo and Father Goñi, in a bilander, set sail for the port of San Ignacio, Sinaloa, to refit for a pearl gathering expedition to California. A few hours later Captain Guzman and Father Kino, in the Concepcion, steered for the Yaqui River, to refit for an expedition to explore the California coast in search of a better site further north. Equipping his launch, Atondo, with Father Goñi, recrossed the Gulf, and spent the greater part of August and September in pearl hunting, but with very slender results. By September 22 he had returned to San Ignacio.

Landing at the Yaqui River mouth on May 11, Guzman and Kino went with their party to recuperate at the mission of Father Cervantes at Torin, and on the nineteenth Kino went on to visit the Father Rector, Diego de Marquina, at the mission of Raun. At these missions supplies were gathered, and in June Guzman and Kino sailed up the Gulf to the Seris coast. At Salsipuedes Father Kino spent three days with the natives, who begged him to remain among them, promising him horses, provisions, and aid in building a mission. * his visit had a direct connection with Father Kino's advent later in Pimeria Alta. On the way down the Gulf they explored the California coast for a short distance above San Bruno, where they stopped late in August, finding the country now green, after the long drought, and the Indians anxious for their return. Encountering the admiral engaged in pearl fishing, on September 7 they again lost sight of him, and, being short of provisions, they sailed to Matanchel, arriving on September 17, and finding the San Jose there and well equipped for California, but with its captain dead. From Matanchel Father Kino went to Guadalajara, where on October 10 he wrote to the Bishop a long report, and made a fervent appeal for California.

Having returned to San Ignacio in September, Atondo received a dispatch from the viceroy ordering him to maintain the California settlements already undertaken. But as the Concepcion had gone to Matanchel with the soldiers and Father Kino, Atondo could do nothing but follow them thither.

On the last day of October Kino left Guadalajara to return to Matanchel and join Atondo. Just outside Compostela he met the admiral on his way to Mexico. When Kino reached Matanchel on November 12, he learned that by a dispatch of October 31, predicated on the assumption that California had been abandoned, and that the fleet was without occupation, Atondo was ordered to go to meet the Manila galleon, warn it against Dutch pirates, and escort it to Acapulco. This news was most depressing to Father Kino, and again he addressed to the Bishop of Guadalajara an appeal for California.

Atondo also returned to Matanchel, and on November 29 he and Kino sailed in the fleet to meet the galleon. Falling in with it next day, they convoyed it safely to Acapulco. Thence they proceeded to Mexico, where Father Kino lodged at the Casa Profesa. Early in February the viceroy held a council, before which reports on California by Atondo and Kino were read. It being concluded that California could not be subdued by the methods hitherto attempted, it was decided to relinquish the task to the Jesuits, with an annual subsidy from the crown, and on April 11 Kino and Atondo were requested to report the amount needed. But the vice-provincial, Father Marras, rejected the offer, on the ground that the Order did not wish to undertake the burden of temporal administration. It was now decided, therefore, to furnish Atondo the thirty thousand dollars a year which he and Kino had reported necessary. A new expedition was thus about to be undertaken by these two veterans, when an urgent request for half a million dollars came from Spain, together with an order, dated December 22, 1685, to suspend the conquest of California because of the recent revolt of the Tarahumares. Thus was the California enterprise put aside, to be revived twelve years later by Kino and Salvatierra.

Pimeria Alta Beginnings

24 Years of Mission Building and Trail Riding

At this point Father Kino takes up in detail the story of his career in America in his Favores Celestiales, which is printed hereinafter, and the remainder of this sketch will therefore be brief. As soon as he learned that the conversion of California had been suspended, he asked and obtained permission to go to the Guaymas and Seris, with whom he had dealt during his voyages from California to the mainland. Leaving Mexico City on November 20, 1686, he went to Guadalajara, where he secured special privileges from the Audiencia. Setting forth again on December 16, he reached Sonora early in 1687, and was assigned, not to the Guaymas as he had hoped, but to Pimeria Alta, instead.

Pimeria Alta included what is now northern Sonora and southern Arizona. It extended from the Altar River, in Sonora, to the Gila, and from the San Pedro River to the Gulf of California and the Colorado of the West. At that day it was all included in the province of Nueva Vizcaya ; later it was attached to Sonora, to which it belonged until the northern portion was cut off by the Gadsden Purchase.

Kino found Pimeria Alta occupied by different divisions of the Pima nation. Chief of these were the Pima proper, living in the valleys of the Gila and the Salt Rivers, especially in the region now occupied by the Pima Reservation. The valleys of the San Pedro and the Santa Cruz were inhabited by the Sobaipuris, now a practically extinct people, except for the strains of their blood still represented in the Pima and Papago tribes. West of the Sobaipuris, on both sides of the international boundary line, were the Papagos, or the Papabotes, as the early Spaniards called them. On the northwestern border of the region, along the lower Gila and the Colorado Rivers, were the different Yuman tribes, such as the Yumas, the Cocomaricopas, the Cocopas, and the Quiquimas. All of these latter spoke the Yuman language, which was, as it is today, quite distinct from that of the Pima.

When Kino made his first explorations down the San Pedro and the Santa Cruz Valleys, he found them each supporting ten or a dozen villages of Sobaipuris, the population of the former aggregating some two thousand persons, and of the latter some two thousand five hundred. The Indians of both valleys were then practicing agriculture by irrigation, and raising cotton for clothing, and maize, beans, calabashes, melons, and wheat for food. The Papagos were less advanced than the Pimas and Sobaipuris, but at Sonoita, at least, they were found practicing irrigation by means of ditches. The Yumas raised crops, but apparently without artificial irrigation. Much more notable than the irrigation in use at the coming of the Spaniards, were the remains of many miles of aqueducts, and the huge ruins of cities which had long before been abandoned, structures which are now attributed by scientists to the ancestors of the Pimas.

Mission Dolores

The Mother Of All Missions

Father Kino arrived in Pimeria Alta in March, 1687, and began without the loss of a single day a work of exploration, conversion, and mission building that lasted only one year less than a quarter of a century. When he reached the scene of his labors the frontier mission station was at Cucurpe, in the valley of the river now called San Miguel. Cucurpe still exists, a quiet little Mexican pueblo, sleeping under the shadow of the Agua Prieta Mountains, and inhabited by descendants of the Eudeve Indians who were there when Kino arrived. To the east, in Nueva Vizcaya, were the already important reales, or mining camps, of San Juan and Bacanuche, and to the south were numerous missions, ranches, and mining towns; but beyond, in Pimeria Alta, all was the untouched and unknown country of the upper Pimas.

On the outer edge of this virgin territory, some fifteen miles above Cucurpe, on the San Miguel River, Kino founded the mission of Nuestra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows), at the Indian village of Cosari. The site chosen was one of peculiar fitness and beauty. It is a commonplace to say that the missionaries always selected the most fertile spots for their missions. This is true, but it is more instructive to give the reason. They ordinarily founded their missions at or near the villages of the Indians for whom they were designed, and these were usually placed at the most fertile spots along the rich valleys of the streams. And so it was with the village of Cosari.

Near where Cosari stood, the little San Miguel breaks through a narrow canon, whose walls rise several hundred feet in height. Above and below the canon, the river valley broadens out into rich vegas of irrigable bottom lands, half a mile or more in width and several miles in length. On the east, the valley is walled in by the Sierra de Santa Teresa, on the west by the Sierra del Torreon. Closing the lower valley and hiding Cucurpe, stands Cerro Prieto; and cutting off the observer's view toward the north rises the grand and rugged Sierra Azul. At the canon where the river breaks through, the western mesa juts out and forms a cliff, approachable only from the west.

On this promontory, protected on three sides from attack, and affording a magnificent view, was placed the mission of Dolores. Here still stand its ruins, in full view of the valley above and below, of the mountain walls on the east and the west, the north and the south, and within the sound of the rushing cataract of the San Miguel as it courses through the gorge. This meager ruin on the cliff, consisting now of a mere fragment of an adobe wall and saddening piles of debris, is the most venerable of the many mission remains in all Arizona and northern Sonora, for Our Lady of Sorrows was mother of them all, and for nearly a quarter of a century was the home of the remarkable missionary who built them.

Missionary Explorer

Apostle to the Pimas

From his outpost at Dolores, during the next quarter century, Kino and his companions pushed the frontier of missionary work and exploration across Pimeria Alta to the Gila and Colorado Rivers. By 1695 Kino had established a chain of missions up and down the valley of the Altar and Magdalena Rivers and another chain northeast of Dolores. In April, 1700, he founded, within the present state of Arizona, the mission of San Xavier del Bac, and within the next two years those of Tumacacori and Guebavi within the present state of Arizona. Kino's exploring tours were also itinerant missions, and in the course of them he baptized and taught in numerous villages, all up and down the Gila and the lower Colorado, and in all parts of northern Pimeria.

Kino's work as missionary was paralleled by his achievement as explorer, and to him is due the credit for the first mapping of Pimeria Alta on the basis of actual exploration. The region had been entered by Fray Marcos, by Melchior Diaz, and by the main Coronado party, in the period 1539-1541. But these explorers had only passed along its eastern and western borders; for it is no longer believed that they went down the Santa Cruz. Not since that day - a century and a half before - had Arizona been entered from the south by a single recorded expedition, while, so far as we know, not since 1605, when Onate went from Moqui down the Colorado of the West, had any white man seen the Gila River. The rediscovery, therefore, and the first interior exploration of Pimeria Alta was the work of Father Kino.

Not to count the minor and unrecorded journeys among his widely separated missions, he made at least fourteen expeditions across the line into what is now Arizona. Six of them took him as far as Tumacacori, Benson, San Xavier del Bac, or Tucson. Six carried him to the Gila over five different routes. Twice he reached that stream by way of Santa Cruz, returning once via Casa Grande, Sonoita, the Gulf of California and Caborca. Once he went by way of the San Pedro, once from El Saric across to the Gila below the Big Bend, and three times by way of Sonoita and the Camino del Diablo, along the Gila Range. Two of these expeditions carried him to Yuma and down the Colorado. Once he crossed that stream into California, and finally he reached its mouth.

East and west, between Sonoita and the eastern missions, he crossed southern Arizona several times and by several trails. In what is now Sonora he made at least half a dozen recorded journeys from Dolores to Caborca and the coast, three to the Santa Clara Mountain to view the head of the California Gulf, and two to the coast by then unknown routes south of the Altar River. This enumeration does not include his journey to Mexico, nor the numerous other trips to distant interior points in what is now Sonora, to see the superior mission authorities.

Discovering Land Route to California

Blue Shell Conference at Mission San Xavier

After 1699, aside from his search for souls in the Pimeria, Kino's most absorbing quest was made in search of a land route to California. Since the days of Cortes and Cabrillo many views had been held regarding the geography of California, some regarding it as a peninsula and others as an island. Kino had been taught by Father Aygentler, in the University of Ingolstadt, that it was a peninsula, and had come to America firm in this belief; but in deference to current opinion, and as a result of certain observations of his own, he had given up the notion, and as late as 1698 he wrote of California as "the largest island of the world." But during the journey of 1699 to the Gila occurred an incident that caused him to turn again to the peninsular theory. It was the gift, when near the Yuma junction, of certain blue shells, such as he had seen in 1685 on the Pacific coast of the Peninsula of California, and there only. If the shells had come to the Yumas from the South Sea, he reasoned, must there not be land connection with California and the ocean, by way of the Yuma country? Kino now ceased his work on the boat he was building at Caborca and Dolores for the navigation of the Gulf, and directed his efforts to learning more about the source of the blue shells. For this purpose he made a journey in 1700 to San Xavier del Bac. Thither he called the Indians from all the villages for hundreds of miles around, and in "long talks" at night he learned that only from the South Sea could the blue shells be had.

This assurance was the inspiration of his remaining journeys. In the same year, 1700, he for the first time reached the Yuma junction, and learned that he was above the head of the Gulf, which greatly strengthened his belief in the peninsular theory. In the next year he returned to the same point by way of the Camino del Diablo, passed some distance down the Colorado, and crossed over to the California side, towed on a raft by Indians and sitting in a basket. Finally, in 1702, his triumph came, for he again returned to the Yuma junction, descended the Colorado to the Gulf, and saw the sun rise over its head. He was now satisfied that he had demonstrated the feasibility of a land passage to California and had disproved the idea that California was an island.

In estimating these feats of exploration we must remember the meager outfit and the limited aid with which he performed them. He was not supported and encouraged by several hundred horsemen and a great retinue of friendly Indians as were De Soto and Coronado. On the contrary, in all but two cases he went almost unaccompanied by military aid, and more than once he went without a single white man. In one expedition, made in 1697 to the Gila, he was accompanied by Lieutenant Manje, Captain Bernal, and twenty-two soldiers. In 1701 he was escorted by Manje and ten soldiers. At other times he had no other military support than Lieutenant Manje or Captain Carrasco without soldiers. Once Father Gilg, besides Manje, accompanied him; once two priests and two citizens. His last great exploration to the Gila was made with only one other white man in his party, while in 1694, 1700, and 1701 he reached the Gila with no living soul save his Indian servants. But he was usually well supplied with horses and mules from his own ranches, for he took at different times as many as fifty, sixty, eighty, ninety, one hundred and five, and even one hundred and thirty head.

Jesuit Return

Builder of California

he work which Father Kino did as a ranchman, or stockman, would alone stamp him as an unusual business man, and make him worthy of remembrance. He was easily the cattle king of his day and region. From the small outfit supplied him from the older missions to the east and south, within fifteen years he established the beginnings of ranching in the valleys of the Magdalena, the Altar, the Santa Cruz, the San Pedro, and the Sonoita. The stock-raising industry of nearly twenty places on the modern map owes its beginnings on a considerable scale to this indefatigable man. And it must not be supposed that he did this for private gain, for he did not own a single animal. It was to furnish a food supply for the Indians of the missions established and to be established, and to give these missions a basis of economic prosperity and independence. It would be impossible to give a detailed statement of his work of this nature, but some of the exact facts are necessary to convey the impression. Most of the facts, of course, were unrecorded, but from those available it is learned that stock ranches were established by him or directly under his supervision, at Dolores, Caborca, Tubutama, San Ignacio, Imuris, Magdalena, Quiburi, Tumacacori, Cocospera, San Xavier del Bac, Bacoancos, Guebavi, Siboda, Busanic, Sonoita, San Lazaro, Saric, Santa Barbara, and Santa Eulalia.

Characteristic of Kino's economic efforts are those reflected in Father Saeta's letter thanking him for the present of one hundred and fifteen head of cattle and as many sheep for the beginnings of a ranch at Caborca. In 1699 a ranch was established at Sonoita for the triple purpose of supplying the little mission there, furnishing food for the missionaries of California, if perchance they should reach that point, and as a base of supplies for the explorations which Kino hoped to undertake and did undertake to the Yumas and Cocomaricopas, of whom he had heard while on the Gila. In 1700, when the mission of San Xavier was founded, Kino rounded up the fourteen hundred head of cattle on the ranch of his own mission of Dolores, divided them into two equal droves, and sent one of them under his Indian overseer to Bac, where the necessary corrals were constructed.

Not only his own missions but those of sterile California must be supplied; and in the year 1700 Kino took from his own ranches seven hundred cattle and sent them to Salvatierra, across the Gulf, at Loreto, a transaction which was several times repeated.

And it must not be forgotten that Kino conducted this cattle industry with Indian labor, almost without the aid of a single white man. An illustration of his method and of his difficulties is found in the fact that the important ranch at Tumacacori, Arizona, was founded with cattle and sheep driven, at Kino's orders one hundred miles across the country from Caborca, by the very Indians who had murdered Father Saeta at Caborca in 1695. There was always the danger that the mission Indians would revolt and run off the stock, as they did in 1695; and the danger, more imminent, that the hostile Apaches, Janos, and Jocomes would do this damage, and add to it the destruction of life, as experience often proved.

The Padre on Horseback

Endurance Rider

Kino's endurance in the saddle was worthy of a seasoned cowboy. This is evident from the bare facts with respect to the long journeys which he made. When he went to the City of Mexico in the fall of 1695, being then at the age of fifty-one, he made the journey in fifty-three days, between November 16 and January 8. The distance, via Guadalajara, is no less than fifteen hundred miles, making his average, not counting the stops which he made at Guadalajara and other important places, nearly thirty miles per day. In November, 1697, when he went to the Gila, he rode about seven hundred or eight hundred miles in thirty days, not counting out the stops. On his journey in 1698 to the Gila he made an average of twenty-five or more miles a day for twenty-six days, over an unknown country. In 1699 he made the trip to and from the lower Gila, about eight or nine hundred miles, in thirty-five days, an average of ten leagues a day, or twenty-five to thirty miles. In October and November, 1699, he rode two hundred and forty leagues in thirty-nine days. In September and October, 1700, he rode three hundred and eighty-four leagues, or perhaps one thousand miles, in twenty-six days. This was an average of nearly forty miles a day. In 1701, he made over four hundred leagues, or more than eleven hundred miles, in thirty-five days, an average of over thirty miles a day. He was then nearing the age of sixty.

Thus we see that it was customary for Kino to make an average of thirty or more miles a day for weeks or months at a time, when he was on these missionary tours, and out of this time are to be counted the long stops which he made to preach to and baptize the Indians, and to say mass.

A special instance of his hard riding is found in the journey which he made in November, 1699, with Father Leal, the Visitor of the missions. After twelve days of continuous travel, supervising, baptizing, and preaching up and down the Santa Cruz Valley, going the while at the average rate of twenty-three miles (nine leagues) a day, he left Father Leal at Batki to go home by carriage over a more direct route, while he and Manje sped "a la ligera" to the west and northwest, to see if there were any sick Indians to baptize. Going thirteen leagues (thirty-three miles) on the eighth, he baptized two infants and two adults at the village of San Rafael. On the ninth he rode nine leagues to another village, made a census of four hundred Indians, preached to them, and continued sixteen more leagues to another village, making nearly sixty miles for the day. On the tenth he made a census of the assembled throng of three hundred persons, preached, baptized three sick persons, distributed presents, and then rode thirty-three leagues (some seventy-five miles) over a pass in the mountains to Sonoita, arriving there in the night, having stopped to make a census of, preach to, and baptize in, two villages on the way. After four hours of sleep, on the eleventh he baptized and preached, and then rode, that day and night, the fifty leagues (or from one hundred to one hundred and twenty-five miles) that lie between Sonoita and Busanic, where he overtook Father Leal. During the last three days he had ridden no less than one hundred and eight leagues, or from two hundred and fifty to three hundred miles, counting, preaching to, and baptizing in five villages on the way. And yet he was up next morning, preaching, baptizing, and supervising the butchering of cattle for supplies. Truly this was strenuous work for a man of fifty-five.

Another instance of his disregard of toil in ministering to others may be cited. On the morning of May 3, 1700, he was at Tumacacori, on his way to Dolores, from the founding of Mission San Xavier del Bac. As he was about to say mass at sunrise, he received an urgent message from Father Campos, begging him to hasten to San Ignacio to help save a poor Indian whom the soldiers had imprisoned and were about to execute on the following day. Stopping to say mass and to write a hurried letter to Captain Escalante, he rode by midnight to Imuris, and arrived at San Ignacio in time to say early mass and to save the Indian from death. The direct route by rail from Tumacacori to Imuris is sixty-two miles, and to San Ignacio it is seventy. If Kino went the then usual route by the Santa Cruz River, he must have ridden seventy-five or more miles on this errand of mercy in considerably less than a day.

Man of Courage

Peacemaker

Kino's physical courage is attested by his whole career in America, spent in exploring unknown wilds and laboring among untamed savages. But it is especially shown by several particular episodes in his life. In March and April, 1695, the Pimas of the Altar Valley rose in revolt. At Caborca Father Saeta was killed and became the proto-martyr of Pimeria Alta. At Caborca and Tubutama seven servants of the mission were slain, and at Caborca, Tubutama, Imuris, San Ignacio and Magdalena- the whole length of the Altar and Magdalena Valleys - the mission churches and other buildings were burned and the stock killed or stampeded. The missionary of Tubutama fled over the mountains to Cucurpe. San Ignacio being attacked by three hundred warriors, Father Campos fled to the same refuge, guarded on each side by two soldiers. At Dolores Father Kino, Lieutenant Manje, and three citizens of Bacanuche awaited the onslaught. An Indian who had been stationed on the mountains, seeing the smoke at San Ignacio, fled to Dolores with the news that Father Campos and all the soldiers had been killed. Manje sped to Opodepe to get aid; the three citizens hurried home to Bacanuche, and Kino was left alone. When Manje returned next day, together they hid the treasures of the church in a cave, but in spite of the soldier's entreaties that they should flee, Kino insisted on returning to the mission to await death, which they did. It is indicative of the modesty of this great soul that in his own history this incident in his life is passed over in complete silence. But Manje, who was weak or wise enough to wish to flee, was also generous and brave enough to record the padre's heroism and his own fears.

In 1701 Kino made his first exploration down the Colorado below the Yuma junction - the first that had been made for almost a century. With him was one Spaniard, the only other white man in the party. As they left the Yuma country and entered that of the Quiquimas, the Spaniard, Kino tells us in his diary, "on seeing such a great number of new people," and such people - that is, they were giants in size -became frightened and fled, and was seen no more. But the missionary, thus deserted, instead of turning back, dispatched messages that he was safe, continued down the river two days, and crossed the Colorado, towed by the Indians on a raft and sitting in a basket, into territory never before trod by white men since 1540. Perhaps he was in no danger, but the situation had proved too much for the nerve of his white companion, at least.

Kino in Death as in Life

Last Day on the Trail

And what kind of a man personally was Father Kino to those who knew him intimately? Was he rugged, coarse fibered, and adapted by nature to such a rough frontier life of exposure? I know of no portrait of him made by sunlight or the brush, but there is, fortunately, a picture drawn by the pen of his companion during the last eight years of his life, and his successor at Dolores. Father Luis Velarde tells us that Kino was a modest, humble, gentle, ascetic, of mediaeval type, drilled by his religious training to complete self effacement. I should not be surprised to find that, like Father Junipero Sierra, he was slight of body as he was gentle of mind.

Velarde says of him:

"Permit me to add what I observed in the eight years during which I was his companion. His conversation was of the mellifluous names of Jesus and Mary, and of the heathen for whom he was ever offering prayers to God. In saying his breviary he always wept. He was edified by the lives of the saints, whose virtues he preached to us. When he publicly reprimanded a sinner he was choleric. But if anyone showed him personal disrespect he controlled his temper to such an extent that he made it a habit to exalt whomsoever maltreated him by word, deed, or in writing. . . And if it was to his face that they were said, he embraced the one who spoke them, saying, "You are and ever will be my dearest master!" even though he did not like him. And then, perhaps, he would go and lay the insults at the feet of the Divine Master and the sorrowing Mother, into whose temple he went to pray a hundred times a day. After supper, when he saw us already in bed, he would enter the church, and even though I sat up the whole night reading, I never heard him come out to get the sleep of which he was very sparing. One night I casually saw someone whipping him mercilessly. [That is, as a means of penance]. He always took his food without salt, and with mixtures of herbs which made it more distasteful. No one ever saw in him any vice whatsoever, for the discovery of lands and the conversion of souls had purified him. These, then, are the virtues of Father Kino: he prayed much, and was considered as without vice. He neither smoked nor took snuff, nor wine, nor slept in a bed. He was so austere that he never took wine except to celebrate mass, nor had any other bed than the sweat blankets of his horse for a mattress, and two Indian blankets [for a cover]. He never had more than two coarse shirts, because he gave everything as alms to the Indians. He was merciful to others, but cruel to himself. While violent fevers were lacerating his body, he tried no remedy for six days except to get up to celebrate mass and to go to bed again. And by thus weakening and dismaying nature he conquered the fevers."

Is there any wonder that such a man as this could endure the hardships of exploration?

Kino died at the age of sixty-seven, at Magdalena, one of the missions he had founded, and his remains are now resting at San Ignacio, another of his establishments. His companion in his last moments was Father Agustin de Campos, for eighteen years his colaborer and for another eighteen years his survivor, as I recently learned from the church records of San Ignacio. Velarde describes his last moments in these terms:

"Father Kino died in the year 1711, having spent twenty-four years in glorious labors in this Pimeria, which he entirely covered in forty expeditions, made as best they could be made by two or three zealous workers. When he died he was almost seventy years old. He died as he had lived, with extreme humility and poverty. In token of this, during his last illness he did not undress. His deathbed, as his bed had always been, consisted of two calfskins for a mattress, two blankets such as the Indians use for covers, and a pack-saddle for a pillow. Nor did the entreaties of Father Agustin move him to anything else. He died in the house of the Father where he had gone to dedicate a finely made chapel in his pueblo of Santa Magdalena, consecrated to San Francisco Xavier. . . When he was singing the mass of the dedication he felt indisposed, and it seems that the Holy Apostle, to whom he was ever devoted, was calling him, in order that, being buried in his chapel, he might accompany him, as we believe, in glory."

Epilogue

Padre Kino's Legacy

In publishing this great memoir left by Father Kino I am carrying out, after two centuries, a hope expressed in 1705 by Father Tamburini, Father General of the Society of Jesus. Thanking Kino for his heroic work, to the humble missionary in the wilds of the Pacific Slope the dignitary wrote:

"I heartily rejoice that your Reverence may continue your treatise on those missions entitled Celestial Favors, the first part of which you sent us here. I hope to receive the other two parts which your Reverence promises, and that they may all be approved in Mexico, in order that they may be published."

The hope was justified by the merit of the work. Indeed, the rediscovery and the publication of this long lost manuscript, whose very existence has been disputed, puts on a new basis the early history of a large part of our Southwest.

The words of that eloquent writer, John Fiske, in reference to Las Casas, Protector of the Indians, are not inapplicable to Father Kino. He says:

"In contemplating such a life all words of eulogy seem weak and frivolous. The historian can only bow in reverent awe before . . . [such] a figure. When now and then in the course of centuries God's providence brings such a life into this world, the memory of it must be cherished by mankind as one of its most precious and sacred possessions. For the thoughts, the words, the deeds of such a man, there is no death. The sphere of their influence goes on widening forever. They bud, they blossom, they bear fruit, from age to age."

"Kino's Historical Memoir of the Pimeria Alta: Contemporary Account of the Beginnings of California, Sonora, and Arizona."

Favores Celestiales by Eusebio Francisco Kino

Translated by Dr, Herbert E. Bolton with preface and notes.

1919

Download Bolton's Complete Preface to Kino's Historical Memoir of the Pimeria Alta in text file

Click

Memoir Preface

Online in English and Spanish

"Favores Celestiales"

"Kino's Historical Memoirs"

"Kino's Historical Memoir of the Pimeria Alta:

Contemporary Account of the Beginnings of California, Sonora, and Arizona."

by Eusebio Francisco Kino

Translated by Dr, Herbert E. Bolton with preface and notes.

In English in two volumes

Volume 1

Click http://archive.org/details/kinoshistoricalm01kinouoft

Volume 2

Click http://archive.org/details/kinoshistorical02kinogoog

In 1919 Dr. Herbert E Bolton translated Kino a series of reports made to his superiors.Commonly known as "Favores Celestiales" or "Kino's Historical Memoirs," the book is a collection of Kino's writings and his correspondence with the history of his missionary efforts in Baja Calfornia and the Pimeria Alta and his vision for the future.

To view and download text of Bolton's Preface to Kino's Historical Memoirs

Click

Boltons Preface Historical Memoirs

Additional Bolton' Writing

"Jesuits on the Pacific Slope".

Chapter 7 "Spanish Borderlands"

Jesuits on the Pacific Slope

In Spanish in one volume

"Favores Celestiales"

por Eusebio Francisco Kino

The Spanish edition is in one volume with edited with preface and notes by Francisco Fernández del Castillo and Emil Böse. Commonly known as "Relación diaria de la entrada al noroeste" o "Las Misiones de Sonora y Arizona." The book was published by The Archivo General de la Nación (Spanish for "General Archive of the Nation"; abbreviated AGN) of the Mexican national government.

For Entire Book

Cllick http://openlibrary.org/books/OL23309685M/Las_misiones_de_Sonora_y_Arizona