Colorado River and Delta

Kino Explorer

Trip Notes

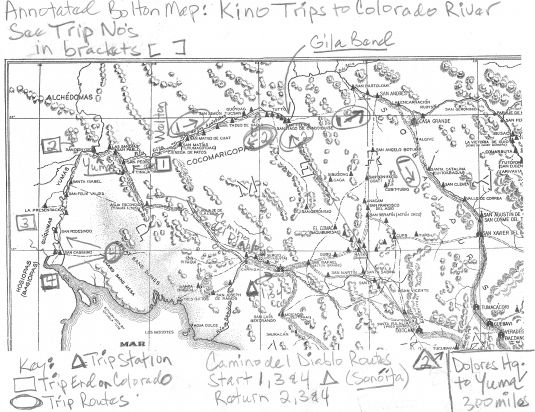

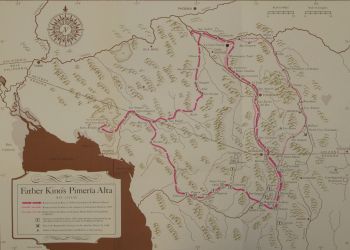

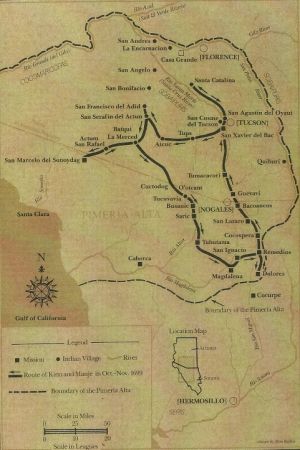

The Trips identified by key numbers [Trip 1] are trips Kino made to the Colorado River area.These trips are part of the trips described in the Explore Sonora and Arizona sub page. The Trips identified by key letters [Trip A] are trips that Kino intended to make to Colorado River but were made to other areas of Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora because circumstances changed on route.These trips are not shown in the annotated map.

Expedition numbers refer to brief descriptions of same travels contained in the Explore Sonora and Arizona sub page. Click Explore Sonora and Arizona page for major Kino expeditions in the Pimería Alta.

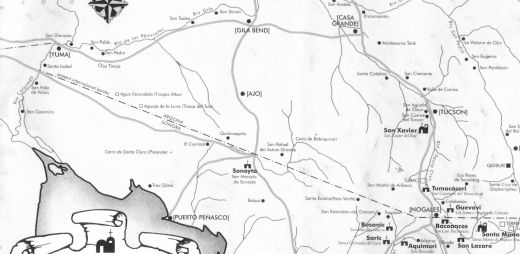

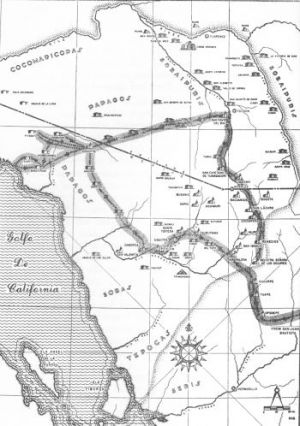

Editor Note: Kino made explorations to the Colorado River and its Delta to discover if a land bridge existed between the North American main land and the Californias. Geographers at the time believed that both Baja and Alta California were part of the world's largest island and could only be reached by ship.

Kino established the first Baja California mission in 1682 at San Bruno near today's Loretto as part of the colonization effort of the Atondo Expedtion. That effort was abandoned after 2 years because the settlers were near starvation and were suffering from scurvy. Food crops did not grow due to drought. Also all supplies had to be expensively shipped across the Gulf of California with its unpredictable winds. Twelve years after the Spanish left, Kino persuaded civil and religious superior to return to the Baja. Kino gained fame as an explorer and map maker by discovering that California was not an island. The surplus from Kino's missions in the Pimería Alta supplied the new missionary effort in the Baja that was financed by the Jesuits Pious Fund and not the Spanish King.

Kino's Exploration of The Colorado River and Delta

Charles W. Polser, S.J.

The Expeditions of 1698 and 1699

1698

[Trip A]

[Expedition 22]

It was the fall of 1698 before another major expedition was mounted. The earlier months of the year had seen the tragic plundering of Cocóspera by the Apaches, the swift and savage retaliation captained by the Piman, Coro, and a resumption of boat-building at Caborca. By September, although still weak and tired from various illnesses and verbally sparring with Padre Mora, Padre Kino took a new captain, Diego Carrasco, and seven faithful Indians on a reconnaissance of the "great river," the Gila. He fully intended to scale the Sierra Estrella but fever cut him down and he languished for some days at San Andrés. His intentions were also to survey the Gulf coast from the heights of the Estrellas, but the natives explained to him that the Gila flowed around these mountains and emptied into the Gulf far to the southwest!

Partially recuperated but stunned by the news about the course of the Gila, Padre Kino and Carrasco wheeled the pack train southward and cut across the heart of Papaguería. Listening to the Indian reports, they knew the trail to the Gulf would be treacherous, but they were determined to accomplish the purpose of the entrada. The Indians at Sonoita directed the explorers toward Pinacate Peak. Kino climbed its volcanic ridges to see the Gulf coast arching away to the west at today's Adair Bay. He had been wrong about the northern limits of the Gulf waters, and the Gila emptied into another great river somewhere to the north and west. From Pinacate, or Santa Clara as it was then called, they turned back and took a shorter and more direct route home through Caborca where fresh supplies and mounts awaited them.

The pace of the trip was typical for Kino. He had traveled some eight hundred miles in slightly more than three weeks. During the trip he took time out to baptize nearly 400 infants, instruct others in the faith, and acquaint himself with hundreds of destitute Papagos throughout the arid land.

Trip One

[Trip One]

[Expedition 23]

After a three month rest at Dolores Padre Eusebio enlisted the aid of Padre Adam Gilg and Captain Manje on a new entrada into the Papaguería. There was nothing scanty about this expedition: he assembled ninety pack animals, eighty horses, thirty-six head of cattle, eight loads of provisions, and a host of Indian vaqueros! Whatever lay to the west, Sonoita was certainly a key and he meant to establish a new mission ranch there to serve as a base camp for the northwest explorations. The massive column picked up even more supplies from faithful Padre Agustín de Campos at San Ignacio and moved around the hills into the Altar valley. They cut a little westward along the southern flanks of the Baboquivari Mountains and camped near the weird peak that dominates the range and the desert vistas. In nine days, on the 16th of February, 1699, they reached Sonoita and prepared for the death-defying crossing of the Camino del Diablo.

The Devil's Highway is one of those ancient trails that even modern man has not reopened. Its route lies along a jagged, parched path from water tank to water hole. The thrust into the desert missed the first promised water; it was almost as if the devil himself were welcoming the explorers. They rode into the night and finally reached a granite tank glistening in the moonlight. Kino and Manje called it Moon Tank, in memory of their midnight discovery. Surrounded by desolate hills and dry plains they scurried from aguaje to aguaje -- Tinajas Altas to Dripping Springs. In four days of hard riding they covered more than 125 miles and finally arrived at the thirst quenching waters of the "Río Grande," the Gila. Exhausted from their adventures along the Camino del Diablo, Kino, Gilg, and Manje rested at a Yuman village just east of the Gila Range where the river turns north before slicing through to the Colorado; they called it San Pedro.

The morning after arriving at the Gila a hundred Yumans padded up the river trail to offer the newcomers gifts and words of welcome. Manje was anxious to go down river, but Kino sensed it would be better to postpone further penetration. There was something astonishing about Kino's sensitivities to Indian protocol. But Manje managed to satisfy his curiosity by riding to a peak in the Gila mountain range from which he saw the junction of the two great rivers, the Gila and the Colorado. No more could the Gila be misnamed the "Río Grande," because the mighty Colorado made the Gila look like a creek.. While recouping their strength and that of the animals, Indians from the Colorado valley brought gifts in exchange for trinkets offered them by the Spanish exploring party. Among them were some curious and beautiful blue shells that Kino recognized as coming only from the “opposite” shores of the Pacific. These shells turned out to be far more significant than mere souvenirs!

When the trio left San Pedro, at the suggestion of Padre Gilg, the Gila was renamed the "Río de los Apostoles," and the Indian villages along the river were each named in a litany of the other apostles as the party moved up river. Reaching the great bend of the Gila, they struck across the desert and negotiated a pass through the Sierra Estrella which deposited them near the now familiar village of San Andrés de Coata. What a marvel Padre Kino must have been to the Pimas who watched this man in his mid-fifties pop out of the desert every few months coming almost always from a different direction!

Once again at Dolores, almost in time for the celebration of the Novena of Grace (March 2-12), word traveled throughout the province that Padre Kino was back from lands of fabled riches. Then, a whole summer was spent in crossing epistolary swords over the worth of vast desert lands accruing to Spain from Kino's explorations. Cynical colonists couldn't see the potential of the land or the people northwest of the Pimería; Kino was “making insects look like elephants and painting grandeurs in Pima Land which did not exist there." Salvatierra, of course, was delighted and encouraged that there might be some new routes to California and he invited Kino again to join in a maritime exploration – but superiors were still fearful of letting Kino get too close to his former mission.

Trip B

[Trip One]

[Expedition 23]

After a three month rest at Dolores Padre Eusebio enlisted the aid of Padre Adam Gilg and Captain Manje on a new entrada into the Papaguería. There was nothing scanty about this expedition: he assembled ninety pack animals, eighty horses, thirty-six head of cattle, eight loads of provisions, and a host of Indian vaqueros! Whatever lay to the west, Sonoita was certainly a key and he meant to establish a new mission ranch there to serve as a base camp for the northwest explorations. The massive column picked up even more supplies from faithful Padre Agustín de Campos at San Ignacio and moved around the hills into the Altar valley. They cut a little westward along the southern flanks of the Baboquivari Mountains and camped near the weird peak that dominates the range and the desert vistas. In nine days, on the 16th of February, 1699, they reached Sonoita and prepared for the death-defying crossing of the Camino del Diablo.

The Devil's Highway is one of those ancient trails that even modern man has not reopened. Its route lies along a jagged, parched path from water tank to water hole. The thrust into the desert missed the first promised water; it was almost as if the devil himself were welcoming the explorers. They rode into the night and finally reached a granite tank glistening in the moonlight. Kino and Manje called it Moon Tank, in memory of their midnight discovery. Surrounded by desolate hills and dry plains they scurried from aguaje to aguaje -- Tinajas Altas to Dripping Springs. In four days of hard riding they covered more than 125 miles and finally arrived at the thirst quenching waters of the "Río Grande," the Gila. Exhausted from their adventures along the Camino del Diablo, Kino, Gilg, and Manje rested at a Yuman village just east of the Gila Range where the river turns north before slicing through to the Colorado; they called it San Pedro.

The morning after arriving at the Gila a hundred Yumans padded up the river trail to offer the newcomers gifts and words of welcome. Manje was anxious to go down river, but Kino sensed it would be better to postpone further penetration. There was something astonishing about Kino's sensitivities to Indian protocol. But Manje managed to satisfy his curiosity by riding to a peak in the Gila mountain range from which he saw the junction of the two great rivers, the Gila and the Colorado. No more could the Gila be misnamed the "Río Grande," because the mighty Colorado made the Gila look like a creek.. While recouping their strength and that of the animals, Indians from the Colorado valley brought gifts in exchange for trinkets offered them by the Spanish exploring party. Among them were some curious and beautiful blue shells that Kino recognized as coming only from the “opposite” shores of the Pacific. These shells turned out to be far more significant than mere souvenirs!

When the trio left San Pedro, at the suggestion of Padre Gilg, the Gila was renamed the "Río de los Apostoles," and the Indian villages along the river were each named in a litany of the other apostles as the party moved up river. Reaching the great bend of the Gila, they struck across the desert and negotiated a pass through the Sierra Estrella which deposited them near the now familiar village of San Andrés de Coata. What a marvel Padre Kino must have been to the Pimas who watched this man in his mid-fifties pop out of the desert every few months coming almost always from a different direction!

Once again at Dolores, almost in time for the celebration of the Novena of Grace (March 2-12), word traveled throughout the province that Padre Kino was back from lands of fabled riches. Then, a whole summer was spent in crossing epistolary swords over the worth of vast desert lands accruing to Spain from Kino's explorations. Cynical colonists couldn't see the potential of the land or the people northwest of the Pimería; Kino was “making insects look like elephants and painting grandeurs in Pima Land which did not exist there." Salvatierra, of course, was delighted and encouraged that there might be some new routes to California and he invited Kino again to join in a maritime exploration – but superiors were still fearful of letting Kino get too close to his former mission.

Trip C

1700

Padre Kino witnessed the turn of the 18th century at Dolores. His work load was heavy and the new California missions under Salvatierra were needing increased assistance. The thrust to the Colorado just meant more work and Dolores was too far away for such involvements as establishing visitas on the Gila and the Colorado. Nor was any new blood being pumped into the Pimería these days. Life was settling into a predictable, hectic routine. That is, until March. While Padre Eusebio was at Remedios, a chieftain from the Gila Pimas arrived with news of the river peoples and a cross strung with twenty blue shells, a gift from the governor of the Cocomaricopas. The cross was accepted with graciousness, but once again the shells made the Padre uneasy. The unanswered question of their origin nagged at his scientific nature.

[Trip C]

[Expedition 25]

A partial solution to the problem of expansion would be to build a mission closer to these new fields of labor, so Padre Kino chose the fertile and extensive ranchería of Bac to become the base for future northwestern entradas. The blue-shell question simmered for a few weeks, and then began to plague him for an answer. With Easter season now over, he set out in late April with ten Indian friends – destination: the Gila pueblos. On the way he would attend to new construction at Remedios and Cocóspera, which was being renovated after its disastrous sacking in 1697. However, news overtook the cavalcade that a contingent of cavalry had ridden into the western desert because of troubles in Soba country. Alone and without escort, it seemed to Kino that a change in plan might be more prudent, so he pulled up at San Xavier del Bac. With the question of the shells very much on his mind, he decided to send out inquiries about the origins of the blue shells. Runners went north, west and even east to call the great chiefs to a "Blue Shell Conference" at Bac. In a matter of days the Padre's messages got a response; chiefs and couriers came with the certain information that the blue shells from the Yumans could not have come from the Gulf because the blue-crusted abalone didn't occur in those dense waters. They had been traded hand to hand from the distant Pacific.

While waiting for the replies, Kino devoted his time to instructing the Sobaipuris in the catechism, and, true to his nature, he directed the laying of foundations for a large church. April 28 was the unforgettable day for the beginning of the church that has since transformed itself into an international memorial. As for Padre Kino, it was time to petition Father Visitor Leal for a permanent transfer to Bac which would place him much closer to the new mission field. He saddled up and rode south toward Dolores with a whole new future on his mind. At dawn on May 3, Kino was preparing to say Mass at San Cayetano de Tumacácori when he was handed a letter from Father Campos at San Ignacio. It was an urgent summons for him to intervene in the scheduled execution, May 4, of a prisoner in the custody of the soldiers. Riding until midnight, he rested at Imuris, reaching San Ignacio at sunrise – just in time to celebrate Mass and save a poor Piman from death. Such was Kino’s whole life in the saddle – long treks in the desert, rapid rides in the cause of justice and mercy, and tedious journeys bringing food and supply to distant Indian tribes; there was no casual rest for the Apostle to the Pimas.

No sooner was Kino back at Dolores than word came from Leal that permission was granted for the transfer to Bac –he only needed to wait for a replacement, a replacement that never ever came. With confidence and expectation at that time Kino dispatched seven hundred head of livestock to start the mission farms at Bac, and he set about making plans for an expedition to the Colorado in the early fall. Everyone was enthusiastic about the prospects of the new missions to the northwest with San Xavier del Bac as the central staging area. Letters were sent off to Salvatierra in distant California about his conviction that there had to be a land passage to those new missions – and a note of encouragement for Salvatierra to join in a fall expedition after harvest and before the annual round-up.

To the Colorado--Finally

Trip 2

[Trip Two]

[Expedition 26]

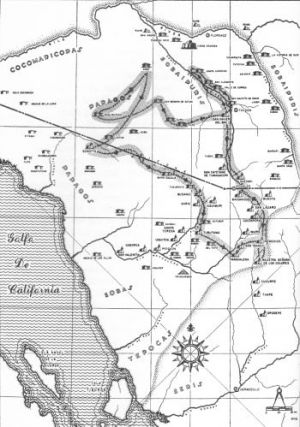

The summer heat had abated; the rains had drenched the desert, and it was opportune to cross the once burning desert. On September 24, 1700, he left Dolores – destination, the juncture of the Gila and the Colorado. This time he took a direct route to reach the big bend of the Gila by crossing the Papaguería. With ten servants and sixty pack animals he wound his way through Remedios, Síboda, Búsanic, and Tucubavia. By the 30th they had reached Nuestra Señora de Merced del Batqui where Kino split the cavalcade in two, sending the majority of the pack animals and horses westward to San Marcelo de Sonidag (Sonoita) to await his return via the Camino del Diablo. He had learned on earlier trips how to negotiate the difficult, waterless wastes. Striking north-northwest to the famous painted rocks of Gila Bend, Kino arrived at El Tutto where Indian messengers had gathered to greet him and bring news of recent victories over marauding Apaches. By sending more than half his retinue to San Marcelo, he had placed constraints on both his route of return and the time he had left to reach the Colorado. But Kino felt himself to be in the element he loved so much, to be under the open skies and meeting new peoples. Every day down stream meant a night spent talking and instructing friendly new Indians; it was hard on his schedule, but it satisfied his sense of apostolate. He had come to the New World to preach the Gospel and eager ears were listening.

On the 7th of October half his allotted time was exhausted. Teaching and baptizing had taken its toll, and anxiety about a return lurked in the back of his mind. Once again, he had neither reached the Colorado nor seen the headlands of California. So this time Kino climbed a small range of hills to view the land with a long range telescope. There was no sea in sight, just expanses of land cut by the meanders of the two huge rivers. The sight was enough for Kino. He concluded that he had seen the lands of California. And his Indian companions were weary of these explorations and uncomfortable because they had hard work to do in rounding up livestock at their villages. It was time to turn back.

The Pimas were relieved when Kino agreed. But then, in the slanting shadows of the afternoon a band of Yumas caught up with Padre Kino insisting that he come to visit their villages on the river. If he didn't postpone the return, he was certain to offend the sensitive and powerful Yuman people. It was a double dilemma between time and fright. Tossing caution to the winds and letting his customary optimism be his guide, Padre Eusebio smiled at the persistent, tearful Indians and agreed to go to their village on the Colorado. He rose before dawn, celebrated Mass and cantered down river, coming across clusters of Indians who had traveled through the night to meet him on the trail. His mule’s gait slowed with each mile as the welcoming throng grew. By noon he rode into the huge Yuma town where over a thousand Indians greeted him in peace. Within another day some five hundred more arrived and word came that hundreds were on their way from north and south along the Colorado!

The Yumas were gigantic in stature, and one of them was the largest Indian Kino had ever seen. It must have been a little nerve-wracking to be the willing captive of such giants. But Padre Kino's own good will and understanding of the Indian ways won a whole new nation in friendship. Staying overnight, he taught and preached under the stars; truly the desert had become his cathedral. Early the next morning on the feast of San Dionisio he christened two sickly adults, naming one after the martyr-patron. Since his duties at Dolores beckoned, he had to leave, but he promised a return – soon.

Prodding his mule, Kino found a fresh relay waiting for him at Las Sandias. He immediately turned south along the arid Camino del Diablo toward Sonoita. He knew the location of the hidden tanks and rode with assurance that they would find water. And again, typical of his explorer’s instinct, he sent the relay team ahead to find pasture and take a siesta, while he trotted up a distant hill to view the sprawling lands of the Colorado delta. Still no sign of the sea. He overtook the others and by sunset arrived at the Tinaja de la Luna (Moon Tank). After a brief respite they rode for three more hours in order to make the next morning’s ride to Carrizal easier and more pleasant. By eight o’clock on October 12, the exploratory party reached San Marcelo – tired from the trip but almost on time. Among experienced travelers along that stretch of desert, Kino’s prowess was olympic. The devil himself must have been grumbling as Kino turned his trail of death into a highway of conquest.

Eight days later at Dolores there was rejoicing to see everyone back safely. Kino lost no time in broadcasting letters to his Jesuit companions and Spanish officials. There was a land route to the Californias. Now all that remained was to make the crossing which would promise to be a logistical nightmare. On his desk was a letter from Salvatierra, written the previous August and telling him of the great need they had for food and supplies because no ship had come from Mexico for fourteen months!

Kino and Salvatierra on the Trail Again

1701

[Trip D]

[Expedition 27]

Padre Juan María Salvatierra in the meanwhile had not been idle. His new mission at Loreto in Baja California desperately needed supplies from the mainland. So the industrious missionary crossed the Gulf in late December, 1700 to secure provisions in Sinaloa. In January he scouted the harbor of Guaymas for a new mission and seaport site which would be more efficient to supply California than the older port on the Río Yaqui. Salvatierra had gotten Kino's reports on the shells and the trek to the Colorado which was ample proof about a land passage. Since he was shipping cattle to California by sea at a cost of $300 a head; even the worst desert in the world would offer a cheaper overland route. Then, by late February both Salvatierra and Manje were rapping at the door of Kino's adobe in Dolores. It had been five years since the two priests were in Mexico together and ten since they rode through the Pimería discussing the future of the missions. Now they were teamed up for an historic journey west.

Before Padre Kino could safely leave Dolores, he had to fortify the mountain missions because the Apaches were opening a new and bold campaign of attack all around the Sierra Azul, the heartland of the Pimería. Salvatierra, on the other hand, knowing Piman fluently from his days as a missionary in Chínipas, went on ahead preaching his way through the valley of the Río Magdalena. A week later Kino caught up with the party at Caborca, and they set out for Sonoita where provisions were being assembled. This time, however, the explorers were determined to bypass the Devil's Highway and find a direct route to the mouth of the Colorado so certain were they that the Gulf terminated at this latitude.

What might have been one of the most significant expeditions of the careers of both Kino and Salvatierra was bungled by a half-wit Indian guide. Apparently that summer, trustworthy guides came at an unpayable premium; already some had refused to disclose watering places on the trail up from Caborca. Salvatierra wanted to go due west from Sonoita which would have brought them north of Pinacate into impassable sand dunes in the Gran Desierto. Kino listened to the Indian guides who favored a passage south of Pinacate. Manje argued for the only rational path -- the Devil's Highway.

Kino prevailed. They turned south around Pinacate onto the horrifying volcanic mesa spewed out by the burned-out mountain. All Salvatierra could think of was what the world would look like after the final ordeal by fire. All they encountered -- save for a few destitute Indians and a withered centenarian -- were ashes, boulders, and sand. Water became a critical problem, particularly for the animals. The guides recommended a trail along the Gulf shore, so they inched across the searing boulders and sand. For three days they searched out a way; it was hopeless. The water at Tres Ojitos just north of modern Puerto Penasco was insufficient and the remainder of the pack train they had left at the foot of Pinacate had to be brought back to water. Reluctantly they turned back.

Having replenished their supplies at Sonoita, they set out again toward the north, but the Pima guides refused to enter into Yuman territory. It was a bad show all around. But the trio did manage to climb a steep, high peak north of Pinacate and from its heights they viewed a sunset glinting on the not so distant California mountains. Salvatierra was satisfied, but Kino and Manje were disgruntled. By violating their unwritten law of conquering the tierra incognita by known quantities, they lost the marvelous opportunity to link the Californias inseparably to the Pimería during their lifetimes. Realizing that neither time nor supply was on their side, the leaders returned to San Marcelo de Sonoita. Salvatierra, now even more anxious about California’s survival hastened straight back to Cucurpe and to the Yaqui; he was back at Loreto in a month. Kino and Manje split off and returned via San Xavier del Bac because of their great concerns about peace in the Pimería – only to learn on arrival that the Pimas had struck a mighty blow against the Apaches who had been marauding in the region when the expedition was forming.

Editor Note: Finding a land route to supply the newly restarted Baja missions was urgent since the principal supply ship, the San Fermin, had sunk and the frigate San Jose was badly in need of repairs.

The Crossing of the Colorado

[Trip Three]

[Expedition 28]

Word spread through the Pimería of the new confirmations of Kino's discoveries. Another expedition was planned by the indefatigable trio for October. But Salvatierra had to beg off because Mission Loreto in California lacked horses to explore the west side of the Gulf. Manje unfortunately was caught in a reshuffling of assignments when a missionary in the mountains pleaded for a punitive force against hostile with doctors. More ominous than anyone realized, however, was the replacement of General Jironza whose lifetime appointment over the Flying Company was dissolved in favor of General Jacinto Fuensaldaña, the military governor of the Province of Sinaloa. Surreptitiously the wily miner from Valladolid had purchased the title at the same time he falsely accused Jironza before the King. So Kino was left holding the reins of the expedition all alone, blissfully unaware of the social tempest the incoming commander would unleash across the Pimería. He was a past master of extortion and bribery.

Kino was now keenly anxious to reach the headlands of California that were known only to him through the long lens of his telescope. With the Pimería safe and secure, the crops harvested, and the round-up complete, he set out on November 3, 1701. Remaining resourceful as ever, he opened yet another new route westward across the Papaguería and along the Camino del Diablo to San Pedro on the Gila and San Dionisio at the junction of the rivers. Hundreds of Yumans and Pimans thronged around the Blackrobe just as they had done the year before. Kino was in his element, but as the cavalcade moved south along the Colorado, fear gripped one of the Spanish servants. A full quarter hour had elapsed before Padre Kino realized the poor Spaniard had ridden off in terror of his life. Two Pima cowhands chased after him on the fastest horses in the train, but they could not catch the timid, terrified man. No doubt he would hatch some choice rumors to exonerate his cowardice. Well, it wouldn't be the first time rumors reached the Pimería that Kino had been eaten alive by angry savages.

Padre Kino was touched in observing that the Yumas and the Quiquimas were fascinated by the celebration of the Mass. He was amused by their reaction to the horses and mules which they had never seen before. When the Quiquimas were told that horses could run faster than the Indians, they scoffed incredulously. So the Dolores cowboys arranged a race and the fleet looted Quiquimas dashed ahead of the ambling horses; then the spurs were put to their flanks and the galloping steeds passed the astonished natives in a victorious cloud of dust.

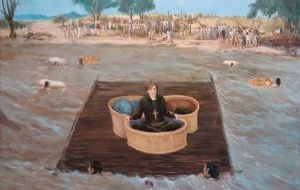

The horses may have been excellent for exploration, but they needed to have the brush cleared away in order to negotiate the river banks. It was obvious they couldn't swim the swift Colorado. Yet the Quiquimas insisted that Kino visit their lands on the opposite side. Nothing could be more agreeable because Kino was hoping to reach the shores of the great South Sea still ten days to the west.

Dry timbers were lashed together for a raft, and the horses were led toward the shaky craft; however, the horses mired down and shied from the strange surface of rippling timbers. Even Padre Kino was reluctant to get his boots wet -- not because he was fastidious, but he knew too well how essential good footgear is to the desert explorer. So the Indians fastened a large waterproof basket on the raft and Kino carefully sat down in his private compartment for the historic crossing of the Colorado.

His sojourn in Quiquima land was brief but hospitable. He knew he had to return to Dolores because the Spaniard who deserted him might cause untold troubles for the Indians of the west should the garrison at Real de San Juan or Fronteras mount a search for a "missing" Padre Kino. At least Kino was now absolutely sure the Gulf ended to the south of the juncture of the Gila and the Colorado and that a land route to Loreto was possible. Back on the east bank of the river the Padre was laden with two hundred loads of foodstuffs as gifts from the Quiquimas. What he gratefully accepted he graciously gave to the needy Yumas whose crops had failed that year.

The news of the crossing of the Colorado hardly jolted the Pimería, now accustomed to the rapid advances made by the aging Padre on horseback. Everyone realized the immense importance of a land route, but one suspects that the Indian raids along the whole northern perimeter were sapping the Spanish strength. Back in Dolores by December 8, Kino the cartographer redrew his famous Paso por tierra map of 1695. The lines of rivers and locations of towns and villages he put in place became one of the best known maps of northern New Spain and spread all over Europe after its initial printing.

Kino's Account of the Trip To The Colorado River Delta

November 1701

Book III.

Of My Expedition Of Two Hundred Leagues To The Quiquima Nation Of Upper California,

And To The Very Large, Very Fertile, And Very Populous Rio Colorado,

Which Is The Real And True Rio Del Norte, 1701.

Click

November 1701 Colorado Trip

"Favores Celestiales"

By Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J.

"Kino's Historical Memoir of Pimería Alta; A contemporary Account of the

Beginnings of California, Sonora, and Arizona" [Vol. 1] 1919

Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, Translator and Editor

Tragedy on the Trail

1702

[Trip Four]

[Expedition 29]

No one could break free for the next entrada of 1702 except for Kino's old Jesuit stalwart, Padre Manuel González, who had first introduced Kino to the Pimería. His health was not the best, but his spirit was lifted high by the reports of new peoples and new lands to the west The cavalcade that formed at Dolores in early February was worthy of the two missionaries. One hundred and thirty horses and mules, laden with provisions, were the core. Kino would amplify that with some of the 1000 head of cattle at Síboda! The whole Spanish colony must have been dumbfounded to think that Padre Kino with one other priest-companion and a few cowhands from Dolores could move herds of animals in perfect peace across the open desert when they couldn't keep a goat or a mine secure for a month.

Padre González was a perfect trail companion. Of Mexican birth and just as old as Kino, he was as warmly received as Kino and equally enthusiastic about the extensive mission foundations that could be set up on the Colorado. Crossing the Papaguería had become almost routine except for the fact that Kino was now increasing the number of ranches along the route to guarantee food and relays for the growing size of the expeditionary forces. Leap-froging along the water tanks and holes of the Camino del Diablo, they reached the Yumas by March 1, 1702, Ash Wednesday. Little did either realize how much of a Lenten penance this journey would inflict! The pair directed the pack train south from San Dionisio and studied ways of crossing the immense river. The difficulties remained the same: the horses mired down and the rafts were useless. To complicate the problems, Padre González became very ill. Pain and hardship were constant companions to any missionary, so the discomfort Padre González experienced along the trail was in his mind nothing out of the ordinary. But the long hours in the saddle had aggravated an old hemorrhoid condition, and the rugged travel and exposure to winter weather was not helping at all.

Padre Kino now realized it would be impossible to cross the river and penetrate to the Pacific coast. No time could be lost in getting González back to help. The extreme urgency can be learned from the fact that Padre Kino turned due east from where he was on the Colorado! He committed himself to crossing the sand dunes of the Gran Desierto, the Sahara of Sonora. Howling winds lashed the company with stinging sand. The animals and men sank in the dry drifts making every step in advance an agony of frustration. They had fought their way nearly forty miles, about half-way to Pitaqui Peak, when they simply had to give up. They retraced their vanished steps and turned back along the more reliable river trails. Padre González braved his painful condition down the Devil's Highway, to him now so appropriately named. Reaching Sonoita, he rested for three days but his condition worsened. Loyal Pimas placed him on a litter and carried him on their shoulders across the desolate Papaguería. Already at the watering tank of Santa Sabina, Kino administered the last rites to the weak and nearly unconscious Blackrobe.

Padre Ignacio Iturmendi, the young missionary of Tubutama, met the desperate and now bedraggled cavalcade a few leagues outside of the village. Word had spread quickly of the expedition’s predicament. González was lingering between life and beckoning death; nothing brought him relief or strength. Kino dispatched urgent pleas for medical assistance in the vain hope that someone’s skills could alleviate Padre Manuel’s distress. It was not to be. In ten days he died.

Curiously enough those three Fathers who met under such trying circumstances would all be dead within ten years, and each would lie buried in the same chapel for centuries awaiting discovery and the honors of historical fame.

The death of Padre González was a blow, but the loss did not diminish the important findings of the expedition. A land passage to California was beyond a dream; it was hard truth, and proven. A mainland port on the Pacific could at last end the agony of anxiety which dogged the Manila galleon; it could mean naval supremacy for the whole hemispheric coast; it would halt the advance of Russia into the New World. And above all it would mean an earlier Christianization for the tens of thousands of Indians hunting and scrabbling out an existence in the chaparral of the Southwest.

Obviously, the loss of an experienced missionary like Padre Manuel on an expedition of exploration fanned the flames of criticism. Nor was the Pimería the same under the surly leadership of Fuensaldaña and his nephew Gregorio Tuñón y Quirós. Jironza had his critics and his supporters who were astonished at his sudden removal that had overtones of expansionist politics. Who would ultimately control the fortunes to be ushered in by a villa on the Colorado? How could anyone allow this system to expand to the Colorado or beyond? How could anyone justify Kino’s trips into the unknown interior? No wonder he had to spend so much time writing and arguing his case.

From "Kino: A Legacy"

By Charles W. Polser, S.J.

Pages 60 - 70

"California No Es Isla, Sino Penisla"

Kino Crossing the Colorado River

Artist José Cirilo Ríos Ramos

Kino's Exploration of Colorado River and Delta

Timeline and Summary

Time line with key references to Maps and Files

[Trip A]

[Expedition 22]

22 Sep. 1698

Fourth Northern Exploration. Travels to Gila River near Casa Grande and treks southwest over the desert lands of the O'odham (Desert Pima) to the Pinacate volcanic field immediately north of present day Puerto Penasco. From Pinacate Peak Kino believes he sees the head of the Gulf of California. See Map [Trip A] (file 09 )

[Trip 1]

[Expedition 23]

7 Feb. 1699

First Colorado River Exploration. Travels the desolate Camino del Diablo ("Devil's Highway”) and ends the exploration just short of the Gila River's junction with the Colorado River. Manje sees the junction from a mountain peak. Returns by visiting villages on the Gila River and Santa Cruz Rivers. Kino's Colorado River Explorations occur from 1699 to 1701.

Stops west of Welton at north end of Gila Mountains

[Trip B]

[Expedition 24]

24 Oct. 1699

"Flying Mission". Halts a planned trip to the Colorado River at Tucson and travels to present day Sells and north to San Francisco del Adid. Then Kino and Manje leave main party and ride south 300 miles in 5 days to O'odham villages from Merced to Sonóita (near Lukeville) and then end their "flying mission" at Busanic - 15 miles southwest of Nogales.. .

20 Mar. 1700

Blue Shell Cross. Receives a gift of a wooden cross strung with 20 blue abalone shells delivered at Remedios from the Cocomaricopas living on the Gila River just east of its junction with the Colorado River.

[Trip C]

[Expedition 25]

Apr. to May 1700

San Xavier Blue Shell Conference. Halts another planned trip to Colorado River at Bac. Begins construction of the first church of Mission San Xavier del Bac. Calls "Blue Shell Conference” and the Native leaders living throughout Pimería Alta meet at Bac and confirm that a land passage to California is possible based on the overland trade of blue abalone shells. On return trip Kino rides 75 miles in less than 24 hours to San Ignacio to save Native man from execution. Back at Dolores, Kino splits herd and sends 700 head of cattle to Bac. His Jesuit superiors grant Kino permission to move his mission headquarters from Dolores to Bac but his replacement at Dolores never arrives.

[Trip 2]

[Expedition 26]

Sep. 1700

Second Colorado River Exploration. Travels north around Baboquívari Mountains and by present day Sells to Gila Bend and follows Gila River west and meets Native peoples at the Colorado River. More than 1,500 people from various tribes living along the Colorado River travel to greet Kino at Quechan village near present day Yuma. From a mountain peak looks south and sees the Colorado Delta and the head of the Gulf of California. Returns via the Camino del Diablo. Stops at Yuma

1701

War of Spanish Succession begins in Europe. Spanish King diverts funds for additional missionaries to pay for war against powers who oppose the unification of France and Spain under the Bourbon kings.

[Trip D]

[Expedition 27]

Feb. 1701

North Gulf Coast and Pinacate Exploration. Unsuccessful attempt to reach Colorado River delta by traveling in the Gran Desierto along waterless Gulf coast. Kino and Salvatierra climb Pinacate Peak and see clearly the head of the Gulf of California.

1701

Famous Map. Kino draws "Passo por Tierra" showing land passage to California. (file 10)

[Trip 3]

[Expedition 28]

3 Nov. 1701

Third Colorado River Exploration. Travels via Camino del Diablo and crosses Colorado River on a raft to present day state of California. Kino urges that peace be made among the warring Quechans (formerly Yumas), Quíquima, Cugane, Hogiopa (Cocopah) and Pima tribes. Kino organizes food relief from the Quíquimas to the starving Quechans whose crops had failed.

Stops south of San Luis

[Trip 4]

[Expedition 29]

11 Mar. 1702

Fourth Colorado River Exploration. Travels south of Colorado River delta into northern most Baja California. Sees sun rising over Gulf of California toward the mainland of Mexico - proof that California is not an island and that a land passage exists. Fellow explorer Father Manuel González dies on return trip on the trail at Tubutama.

Stops at Colorado River Delta and head of the Gulf of Mexico

1703 - 1711

Jesuit superiors direct that Kino's main work in addition to missionary duties is to supply Salvatierra's restarted missions in Baja California. Kino was not given permission to make further explorations to the Colorado River. Kino builds churches at missions in present day Sonora and supplies the Baja missions. Native people from present day Arizona especially from the village of Bac travel into Sonora to help Kino.

For Expeditions 30 through 37,

Click Explore Arizona Sonora Page

To Return to Explorer Section Page,

Click Explorer Page