The Grave Site History

Kino Grave Discovery

Page 1

"Finding Father Kino's Grave Summary Flyer"

Two Pages

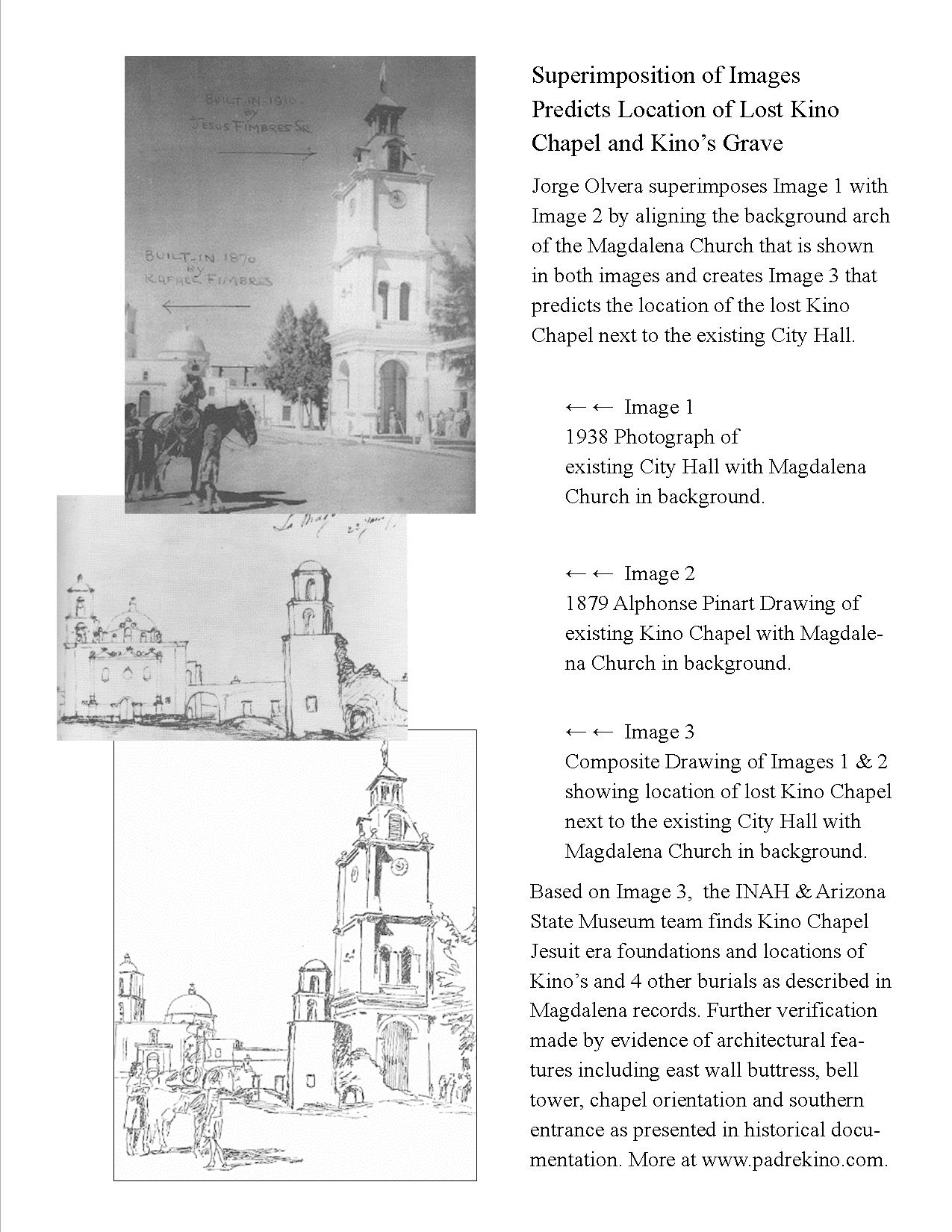

Superimposition of Images Predicts

Location of Lost Kino Chapel and Kino’s Grave

Page 1

Two Page Summary Flyer

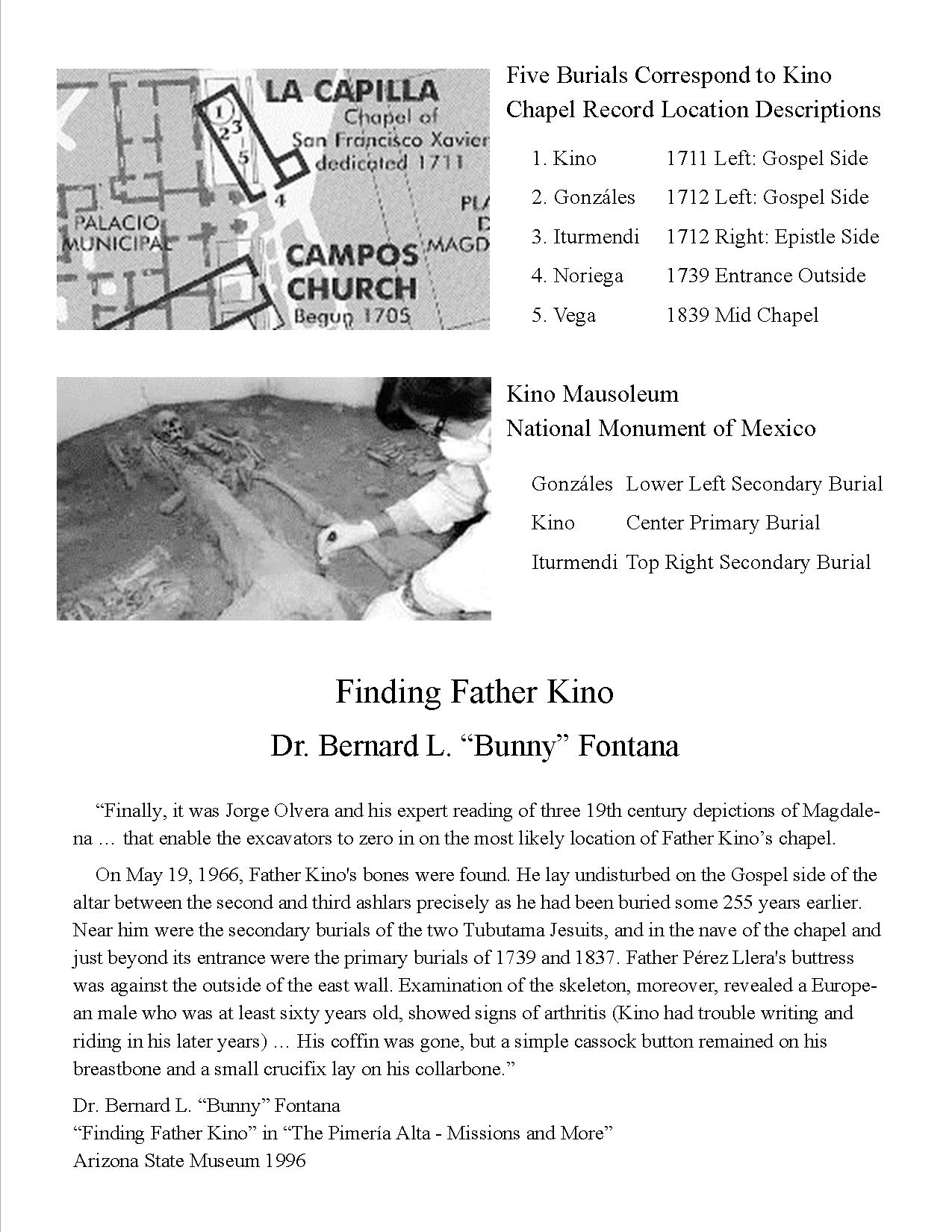

Location of Five Burials Correspond to Burial Records

Page 2

To Download Two Page

"Finding Father Kino's Grave Summary Flyer"

Click

Summary Page 1

Summary Page 2

The Documentary Record Before Digging

The Lost Grave

Bernard L. Fontana

Foreword

"Finding Father Kino... "

I recall the day in 1965 when Professor Moreno and Jorge Olvera arrived in my office in the Arizona Sate Museum in Tucson to say they had come to Sonora to locate the bones of this late 17th- and early 18th-century Jesuit missionary. About all that was known at that moment was that Father Kino had died on March 15, 1711, and had been buried on the Gospel side of the altar in a chapel just completed by him in Magdalena, one dedicated to the Jesuit apostle to the Indies, San Francisco Xavier. No one knew where the chapel was located. In deed, no one knew with certainty that the Magdalena, Sonora, of the present, with its mission church completed by a Franciscan in 1832, was the same Magdalena of 1711 or was anywhere near it. Villages in the Sonoran Desert, occasionally devastated by sudden flooding or made uninhabitable because of epidemic diseases or relentless attacks by Apaches and other hostile Indians, had been known to change their locations.

Kino had worked with Father Agustin de Campos in 1705-1706 to build the first church dedicated to Santa Maria Magdalena. Magdalena's second religious edifice was the chapel dedicated to San Francisco Xavier that Kino dedicated in 1711 and where he was immediately afterward buried. Jesuits after Kino had difficult times in the Pimeria Alta. In 1751 the Piman Indians among whom they were working rebelled, and while Spanish soldiers quickly quelled the uprising, problems lingered.

In 1767 the Jesuits were expelled by King Carlos III from all of New Spain, the Pimeria Alta included, and the following year their Pimeria Alta missions were manned by members of the Order of Friars Minor, or Franciscans. The Franciscans introduced their own brand of mission methodology, one that included construction of churches and other buildings out of more durable materials than those that had been used by the Jesuits. A Franciscan completed a mission church in Magdalena in 1832. The scene, as viewed through the eyes of archaeologists or other historians of material culture, was chaotic.

The entire Mexican project struck me as one almost certainly doomed to failure, especially considering that many others in this century-and some of them as recently as the early 1960s-had diligently tried to find Father Kino's remains and had failed.

I was, of course, wrong. I altogether underestimated the shrewdness of Jimenez Moreno, who devised a multi-faceted strategy, and the devotion and tenacity of all those who became a part of the binational team engaged in the search.

It should be said from the outset that the excavations that ultimately uncovered Father Kino's grave were only marginally "archaeological." The effort was, quite frankly, a treasure hunt, with Father Kino's skeleton being the treasure. The sole purpose of the endeavor was to locate his remains. No one was being asked, or expected, to un cover and interpret architectural and other artifactual evidence to elucidate the history of Magdalena and its environs. The team worked under ridiculous time constraints and budgetary restrictions that would have thoroughly discouraged almost any other group of investigators.

Bernard L. Fontana

Foreword from "Finding Father Kino

The Discovery of the Remains of

Father Eusebio Francisco Kino 1965-1966"

The Lost Kino Chapel

William W. Wasley

"Archeological Notes on the Discovery of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino." 1966

"Our search had been "like looking for a needle in a haystack, but first we had to find the haystack!" There was little hope of finding or identifying Father Kino unless we could first find and positively identify the chapel in which Kino had been buried. This, in a nut shell, was our basic archaeological problem: it cannot be more simply stated. Yet at times the solution appeared elusive if not impossible."

Dr. William W. Wasley

"Archeological Notes on the Discovery of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino."

1966

To Go To Discovery of Kino Chapel Page

Kino Grave Discovery - page 2

Click Grave - Chapel

The Search For Kino's Grave

Digging in Magdalena Plaza and Church Archives

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

The Discovery of Padre Kino's Grave

Kino: A Legacy ..."

While preparations for the Kino Memorial Statue neared completion, the search for Kino’s grave was shelved. In February, 1965, the nation was introduced to the prominence of Padre Kino by the unveiling of his statue in the nation’s Capitol. Little did the people responsible for the statue realize what they had wrought concerning the discovery of Kino’s grave. Mexico, too, was justly proud of Padre Kino; the Mexican people were not about to forfeit their share in Kino’s fame. Hence, at the request of Mexican President Diaz Ordaz, the Secretary of Public Education, Agustín Yáñez, commissioned Professor Wigberto Jiménez Moreno, the director of the Department of Historical Investigation of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), to find the remains of Padre Kino. It was June 30, 1965. Whatever legal log-jams the Americans conjectured over in the search for Kino’s grave were swept away by the executive order of the Mexican federal government. Professor Jiménez Moreno, Dr. Jorge Olvera, the colonial art historian, and Professor Arturo Romano, the physical anthropologist of the National Institute, began a systematic search of the archives for information about the grave.

A quick trip to the Sonora frontier in August, 1965, acquainted Jiménez Moreno and Olvera with their newly inherited problem. Rumors and opinions varied on all aspects: the grave, the chapel, the remains, and their transfer. Professor Jiménez Moreno retired to Mexico City profoundly aware he had more on his hands than a casual search. Dr. Olvera remained behind to begin the methodical excavations which eventually crisscrossed the site of the ancient pueblo. The traditional Fiesta of San Francisco forced an interruption of work in October. The trenches were back-filled and the investigators took advantage of the recess to evaluate their problem. Professor Jiménez Moreno accurately reassessed the situation. The discovery of the grave and the verification of the remains of Padre Kino would be no simple matter. The ingredients of success would be men and knowledge, both archaeological and historical

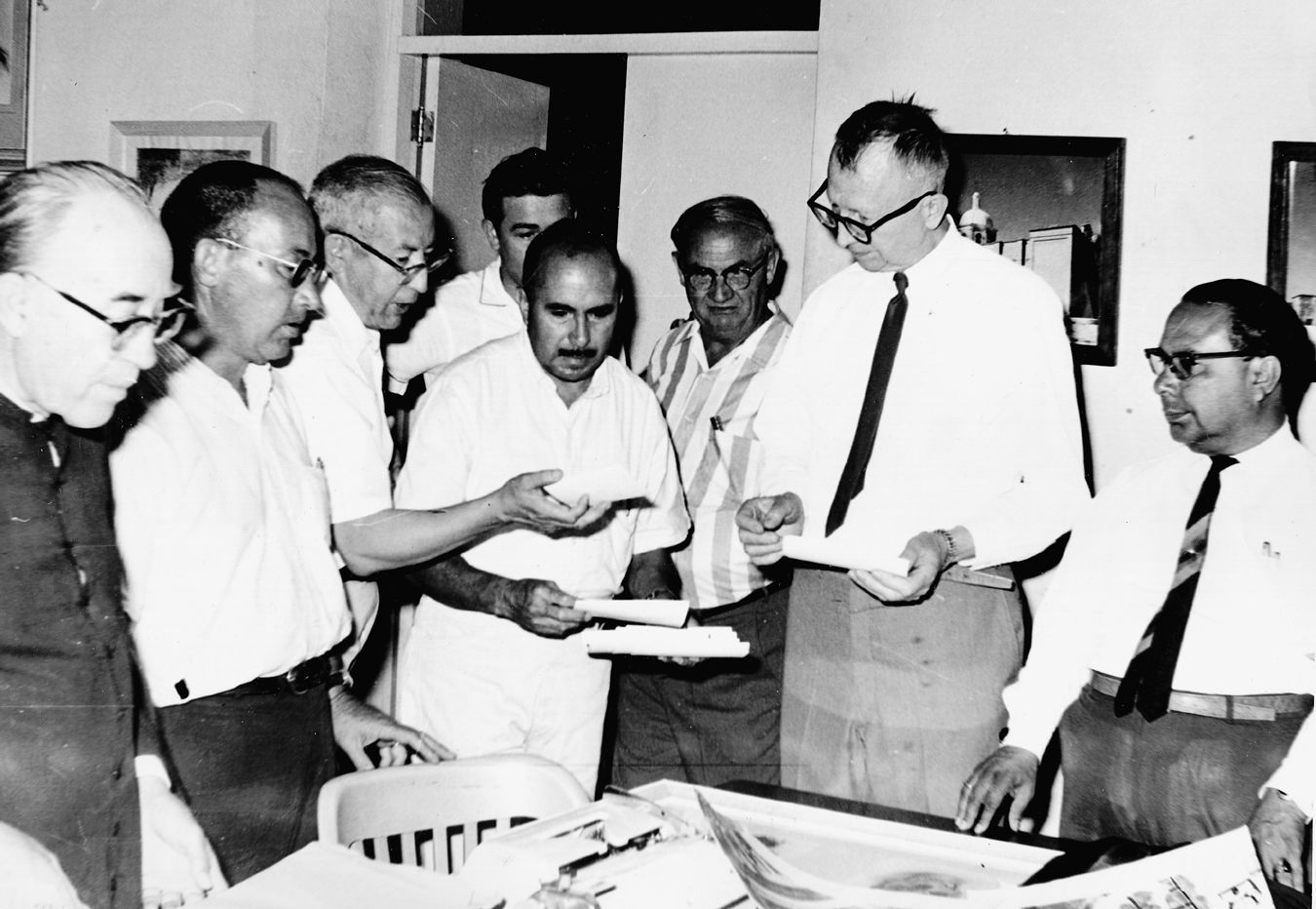

Discovery Team in front row from left to right

Rev. Santos Saenz, Dr. William. W Wasley, Dr. Wigberto Jimanez Moreno

Dr. Jorge Olvera, Dr. J. Matieila and Rev. Ernest. Burrus, S.J.

Not shown; Rev. Kieran McCarty, O.F.M., Dr. Arturo Romano,

Dr. Gabriel Sanchez de la Vega, Rev. Cruz Acuna Galvez, Conrado Gallegos

Dr. Charles W. Polzer, S.J., Dr. James Ayres

It was April, 1966, when the team arrived again in Magdalena. Jiménez Moreno invited other qualified investigators to join the team. Padre Cruz Acuña from Hermosillo pitched in to comb through old diocesan archives and to interview old timers. The Reverend Kieran McCarty, O.F.M., historian of San Xavier del Bac (Tucson), signed on as research historian; his familiarity with Franciscan records aided materially in piecing out the fate of the old chapel. Dr. William Wasley was placed on detached service from the Arizona State Museum; his keen knowledge of the archaeology of the region provided the team with essential knowledge and skills. The chemist from the local clinic, Dr. Gabriel Sánchez de la Vega, gave invaluable service as the man most acquainted with the recent attempts to find the grave.

To the men of Mexico City in 1965 the search for the grave of Padre Kino appeared to be a simple matter. To the same men on the scene in Magdalena in 1966 the search was recognized as enormously complicated, and perhaps impossible. Excitement charged the air of Magdalena as the experts challenged the unknown.

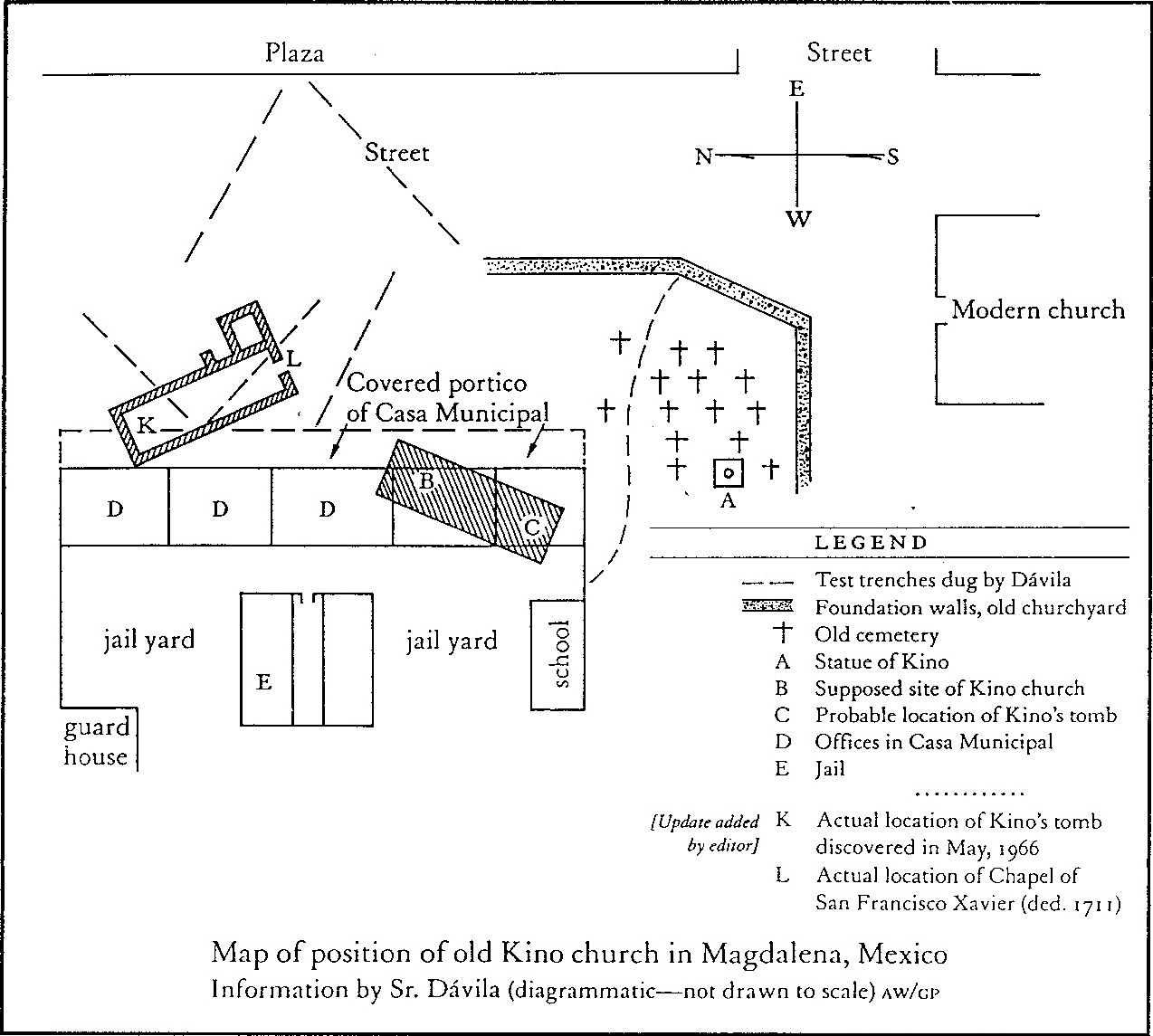

Site of San Xavier Chapel (La Capilla)

Several Feet From Old Magdalena City Hall

Professor Jiménez Moreno understood his problem well. Here was a situation that required solution by a process of elimination. Units of the team spread out from Magdalena to probe each site favored by certain rumors and opinions. No reasonable possibility was overlooked, but one by one they were being eliminated as archaeological and historical evidence piled up. Slowly the circle of probability narrowed to the plaza in front of the Magdalena church. Over two kilometers of exploratory trenches wandered through the town. Work crews exposed foundations of buildings long since forgotten. The earth yielded the bones of countless human beings.

It seemed as though the search would succumb to the intricacies of its own method. Then, the breaks began to come. The historians were building up key clues about the chapel from the archives. The major find was a description of the little chapel of San Francisco Xavier in an 1828 report by don Fernando Grande:

"The chapel of this town is moderate. It is of adobe material. The entrance faces south. There is a moderate little tower in which are located three bells and another small one. It has nothing that draws particular attention. The principal and only altar is in the chancel. On it are set an image of the crucified Christ and another of the Virgin of Dolores; at the feet of the larger carving is the littler one of ordinary quality. And in some niches which form a reredos along the wall of the altar are set the statue of St. Magdalene, the patron of the pueblo (it’s small but well carved), one of St. Francis Xavier, and one of Blessed Joseph Oriol; the latter is imperfectly carved. Midway in the nave of the church is a niche where there is located in a case a large carving of St. Francis Xavier, an object of devotion everywhere in the northwest. It is a beautiful and serious sculpture."

From the burial register two more relevant facts were learned. In 1739 a Spaniard, Salvador de Noriega, was buried at the entrance to the chapel. Nearly a century later a ninety year old Indian resident, José Gabriel Vega, was buried before the niche of St. Francis Xavier.

While the historians read through miles of micro film and dusted off old records, the archaeological teams followed the clues exposed by their trenching. The cement foundations in front of the church which had occupied Dávila years before were soon discounted when it was learned that lime was not used for construction in the Pimería during the earlier Jesuit period. Traces of adobe walls became more evident as the work crews learned the difficult art of distinguishing an adobe foundation from the alluvial deposits natural to the terrain. One wall which ran east and west had attracted the attention of Dr. Olvera who felt that it maintained the proper orientation shown in some mid-19th century sketches of the pueblo. But what is one wall in the middle of a whole town?

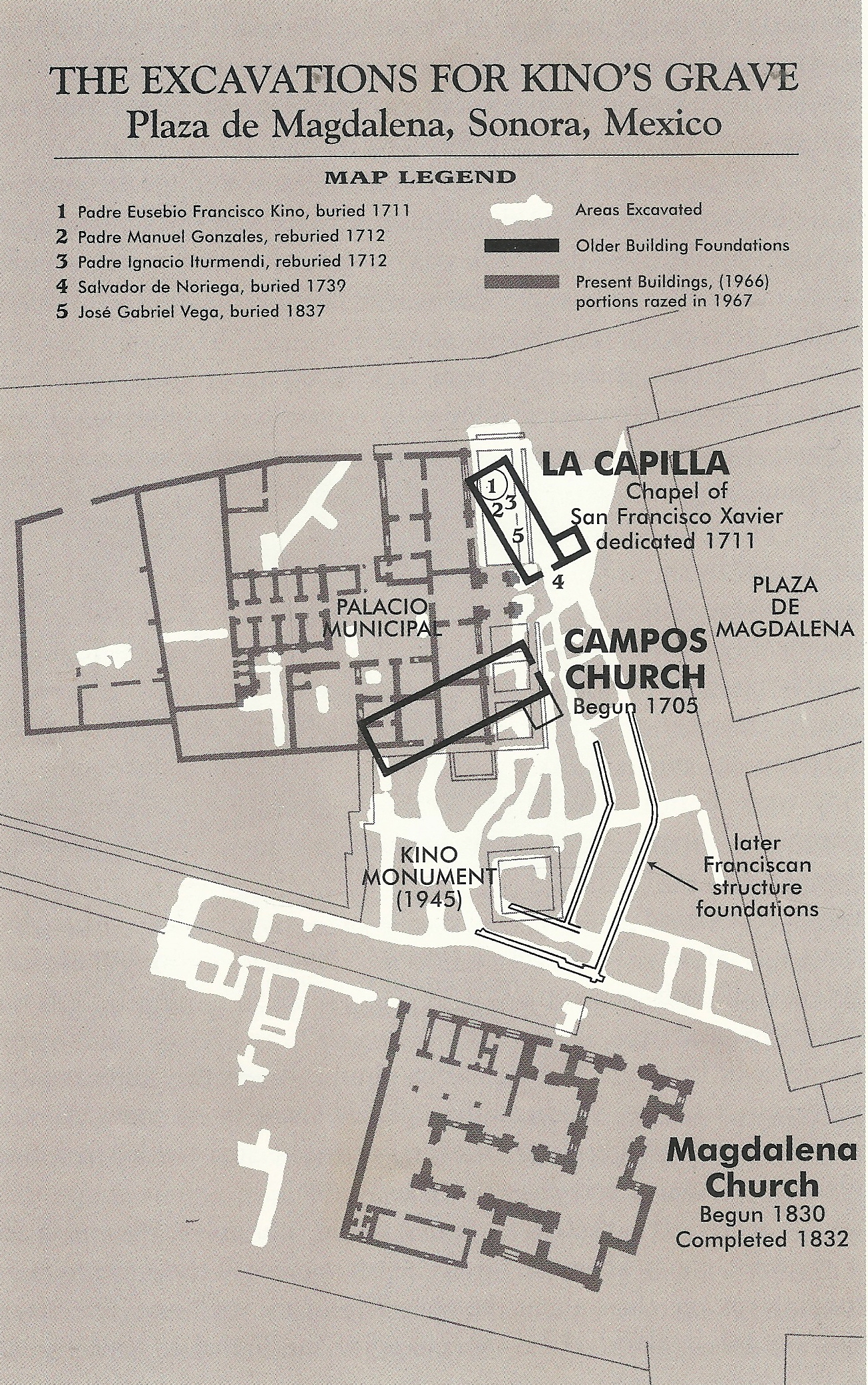

Map of Excavation Areas in Madgalena

Dr. Wasley convinced the team of the need to correlate their findings with known Jesuit ruins in the Pimería; this was a stratagem worked out a year before between Wasley and Polzer, who insisted on the utility of the uncontaminated ruins at Remedios. On the very day Wasley, Olvera, and Romano were making their reconnaissance, the workmen in the trench that followed Olvera’s favored wall came to its end. Professor Jiménez saw that they had really reached a corner. The wall turned toward the City Hall. This was the first clear indication that it might define the foundations of a building.

Earlier in the exploration a crew had followed a lateral trench from Olvera’s wall. Close to the north-south axis of the main trench they exposed a skeleton which Professor Romano identified as that of a European. Everyone regarded the discovery as “Suspect Number One.” But then other pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place. “Suspect Number One” was on the south side of the adobe wall, and now that the long adobe wall to the east of the burial had turned a corner westward, there was little doubt that the Number One Suspect was Salvador de Noriega.

The east wall of the building showed evidence of a small buttress about midway. This corresponded to another historical discovery that Padre José Pérez Llera in 1828 erected a buttress to prevent the wall from further slumping! The corner discovered on the day the team was reconnoitering other missions proved to be that of the apse of the chapel. Cautiously the crews followed the line of the adobe and boulder foundation. The sharp spades cut through the soil ever so carefully. A shovel full of earth spewed into the screen. Nothing. Then at the base of the trench fell a piece of a skull, dislodged from the edge! A cry! Tension mounted as Dr. Wasley, Dr. Olvera, Dr. Romano and Professor Jiménez Moreno carefully exposed the whole skull. Could it be? Could it really be Kino’s? It was 4:45 on the afternoon of May 19, 1966.

Protective Glass Cases Over

Kino's Skeleton Between Reinterred Remains

Padres González & Iturmendi

The entire team concentrated on the complex of trenches that seemed now to be located on the site of the ancient chapel. The skeleton discovered that fateful afternoon was delicately uncovered. The earth within the entire chapel area was cautiously peeled back. Then the key elements began to fall in place without complication. “Kino” was an original burial on the Gospel side of the chapel; the body had rested between the second and third foundation support, just as the burial record of Padre Agustín de Campos said. Then, at Kino’s feet, but closer to the west wall, appeared a “secondary burial,” one that had been transferred from another place. Across the chapel floor area, on the Epistle side of the apse, another secondary burial was uncovered in the packed earth. Fantastic! But predictable if this were really the chapel. In 1712, one year after Kino’s burial in the chapel, Padre Campos transferred the bodies of Padres Iturmendi and González from Tubutama and interred them in the same chapel on the Epistle and the Gospel side respectively.

Midway down the body of the church the excavators came upon another burial of a very old Indian man. Another key slipped into place be-cause 90 year old José Gabriel Vega was buried before the niche of St. Francis Xavier – located half way down the nave! And Salvador de Noriega was still lying patiently at the southerly entrance.

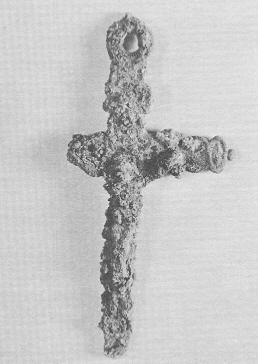

Professor Romano carefully studied the skeleton which lay on the gospel side of the building – if this were really the chapel. The man had been in his 60’s. Kino had been 66. The skull was a classic European type from the Alpine region. Kino was from the Tyrol. The tibia bones of the legs showed a pronounced retroflexion. This was characteristic of the mountain people of Kino’s homeland. When Wasley and Olvera removed the last traces of the wooden coffin which had caved in on the chest of the skeleton, they found a small bronze cross lying on the clavicle. This was typical of the Jesuit missionary of the 17th century.

On May 21, 1966, the team reached the conclusion that it had in fact discovered the long lost remains of Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino. On May 24 the announcement was made to the general public; no doubt remained in the minds of any of the team or the experts called in after the initial conclusion was reached. The Reverend Ernest Burrus of the Jesuit Historical Institute at Rome, who luckily was visiting in Tucson, agreed in full. And finally on July14, 1966, the Academy of History met in Mexico City to review the evidence. Professor Jiménez Moreno presented seventy-two depositions explaining the discovery. Then, Dr. Alberto Caso in the name of the Mexican Academy of History pronounced in favor of the identity of the remains. Padre Kino was found at last.

As with everything that man does, there are always those who doubt. Some wanted the archaeologists to uncover a plaque or headstone. None ever existed, particularly for a man like Kino. He died as he had lived, in poverty and in the presence of his Lord. What the doubters had forgotten was that the monument over his grave was not just a headstone, but a chapel, and not just a cross with a name, but a whole culture.

So conclusive is the evidence which the team under Professor Jiménez Moreno uncovered that if the skeleton had been marked with another name, the anthropologists and historians would have realized someone was trying to play a joke.

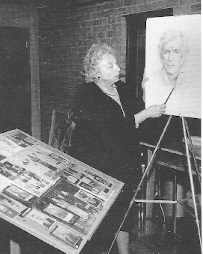

Francis O'Brien Drawing Kino Portrait

But perhaps the most remarkable thing of all is that when the anthropologists were asked to reconstruct the likeness of Kino from his skeletal remains, they shrugged and pointed to a sketch on the wall of the City Hail. There hung the drawing done by Mrs. Frances O’Brien of Tucson. One could hardly come any closer to the human reality. She had sketched his portrait from the salient features of the Chini family as they lived in this century. She had only hoped to approximate Kino’s likeness. Little did she know she had drawn the last clue in the recognition of Padre Eusebio Kino.

Dr. Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

The Discovery of Padre Kino's Grave

"Kino: A Legacy... "

Baroque Crucifix Found On Left Clavicle of Kino's Remains

Kino's Crucifix

Documentary-Fiction Account

Ben Clevenger

By the end of that day, though, they still hadn't proved the remains were Kino's. Nor had they the next. Romano cautioned them: The man wasn't carrying any ID. And he'd reminded them that the only proof they would ever have would be largely circumstantial. "Small proofs," he had said. "We look for many of them and hope they all somehow add up to one big, irrefutable proof. In physical anthropology, that's how we do it. That's the best we can ever do."

Over the next few days, though, they added nicely to their growing assortment of small proofs. They found: the cobblestone pedraplen of the chapel's bell tower, deep in the earth near its east wall; the jumbled bones of Fathers Gonzalez and lturmendi precisely where Campos said he'd buried them-on the left and right sides of the nave, at its north end; the bones of Jose Vega, the Indio, near the middle of the west wall. They already had the skeleton of Noriega, the Spaniard, beneath the doorway along the south wall. Olvera even found the footings of the buttress, deep in the earth just outside the chapel's east wall. .

When the scientists had met again in Romano's field lab, Jimenez wasted no time. "Gentlemen," he said, "we've made certain assumptions about the skeleton in 17B based on the fact that we believe the foundations are those of Kino's chapel. I understand Jorge has found a buttress. Are we now in agreement that we have Kino's chapel? Jorge? Are you satisfied?"

"Absolutely, sir." "Arturo?" Jimenez said.

"I'm convinced of it," Romano said.

"And you, Bill?"

"You bet," Wasley said. "The building is too small for a church. It's the right size for a chapel. The footings are identical to those of the churches at Remedios and Cocóspera - and we know Kino built those. And we have all those bones and a buttress that are exactly where they're supposed to be. Yes, this has to be Kino's Chapel of San Xavier."

"All right," Jimenez said. "Arturo has already assured us that the bones in 17B are those of an adult male, and we know that Kino was sixty-five years old when he died. So we come to the biggest question of all: Arturo, are you now convinced that these are the bones of a western European adult male of the right age?"

Romano nodded. "I'm sure of it."

"Small proofs, but important ones," Jimenez said, and smiled.

But the biggest proof that they'd found Kino would come the next day.

"What is that!" Olvera said, pointing at a vague area of thickening over the rib cage of the skeleton in 17B. The workmen had enlarged the trench, making more space at the bottom. Now the scientists were huddled around the bones, Romano closest, Romano carefully brushing sand and grit from the sternum and ribs in the warm sunlight that streamed in from above.

"Jorge is right," Wasley whispered. "There, on top of the clavicle. Left side. At the proximal end."

Romano cautiously teased more dirt from the sternum and left collarbone. At first the scientists could make out only an ill-defined something, a vague shape that lent an odd lumpiness to the veneer of detritus still covering the clavicle. With gentle strokes Romano worked dirt and sand from its surface. Slowly, gradually, it came into view. Across the left clavicle, corroded but definite and undeniable: a crucifix, maybe two inches in length, the sculpted figure of Jesus still recognizable.

"Madre de Dios," Olvera whispered. His pulse raced in his temples and he felt an odd prickling on the skin of his face.

"Praise be to God," Romano said softly.

"Bronze," Wasley murmured. "Baroque style, seventeenth century-" "The size is right, too," Olvera said, his voice low. "The Jesuits wore such crosses on a cord around their neck." He wondered why he was whispering, why all of them were whispering. His legs felt weak, his mouth so dry he could hardly swallow.

Wasley said, "It's him, isn't it. It's really him. Eusebio Kino."

Olvera nodded. "Madre de Dios," he whispered again. "Yes, it's him."

Ben Clevenger

"The Far Side of the Sea:

The Story of Kino and Manje in the Pimería"

Pronouncement of The Mexican Academy of History

On May 24 the announcement was made to the general public; no doubt remained in the minds of any of the team or the experts called in after the initial conclusion was reached. The Reverend Ernest Burrus of the Jesuit Historical Institute at Rome, who luckily was visiting in Tucson, agreed in full. And finally on July14, 1966, the Academy of History met in Mexico City to review the evidence. Professor Jiménez Moreno presented seventy-two depositions explaining the discovery. Then, Dr. Alberto Caso in the name of the Mexican Academy of History pronounced in favor of the identity of the remains. Padre Kino was found at last.

Dr. Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

The Discovery of Padre Kino's Grave

"Kino: A Legacy..."

After Finding Father Kino

Dr. Bernard L. Fontana

Afterword

Finding Father Kino ...

Father Burrus's seal of approval assured universal accpetance of the discovery's authenticity among historians and other scholars. With a skeptical local public, however, it was another matter.Not privy to the facts uncovered in archives and underground, ordinary people were less sure.

They knew none of the details of the configuration of the San Francisco Xavier chapel, including its south entrance, bell tower, and buttress and its relation to the Campos church; of the significance of the location in the chapel of Salvador de Noriego's bones and those of Fathers Gonzales and Iturmendi; of the evidence from the Pratt, J. Ross Browne, and Pinart sketches; of the importance of a baroque-style crucifix found on the clavicle; nor of the makeup of Jesuit-period foundations. …. Even to this day, doubters remain. And among those unwilling to avail themselves of the facts, there probably always shall.

That Kino's remains were discovered in 1966 has to be regarded as miraculous. The same might be said for the continuation of so much that he set in motion in northern Sonora / southern Arizona more than three centuries ago.

Afterword

Dr. Bernard L. Fontana

Complier and Coordinator

"Finding Father Kino

The Discovery of the Remains of

Father Eusebio Francisco Kino 1965-1966

1998

Arizona Pioneers Society's President Trip Day After Discovery

James M. Murphy

The Journal of Arizona History

Summer 1966

I arrived in Magdalena on Sunday evening, May 22, looked at the entire dig, and listened to the conclusions and findings of the experts, reviewed the books, burial records, pictures, sketches, and other documents used to prove the location of Father Kino's grave. In addition, I examined the bones. By the time I had listened to the experts and seen the visual and circumstantial evidence, I too was certain these were the [89] bones of the great Jesuit missionary who worked in Pimería Alta 255 years ago, and who died in 1711.

The expedition seeking the grave of Father Kino was composed of two Mexicans and two Americans. Dr. Jimenez Moreno and Dr. Jorge Olvera are members of the Department of Historical Research in the National Institute of Anthropology and History. Dr. William W. Wasley is Archaeologist of the State Museum at the University of Arizona. Rev. Kieran McCarthy, O.F.M., is Historian at San Xavier Mission, Tucson. Dr. Moreno headed the expedition. Dr. Olvera, a noted architect, is a graduate of Santa Clara University, California. The Mexican Government also brought in Dr. Arturo Romano, a highly respected physical anthropologist, who was in Mexico City while I was in Magdalena. This group worked well together and certainly knew their business. Although my knowledge of the history of Sonora and of Father Kino is only slight, it is sufficient to assure myself that the experts knew what they were doing.

When I looked at Father Kino's bones, I was impressed with the massiveness of the body ― or at least of the chest cage. He was approximately five feet, ten inches tall, and said to have been husky, although in later years he fasted and lost considerable weight. In his youth he had been a teacher and did not become a missionary until he was approximately forty-two years old. He then started a rugged outdoor life, raising cattle, riding, and making long trips across the desert. He suffered from osteoarthritis brought about somewhat by his rugged life. The effect of this is shown on the bones of his spine, knees, hands and feet. The bones in the lower spine are ragged and not smooth lipped as are the bones farther up the spine. He mentioned many times in his diaries that disease and illness forced him to rest a day or more longer than planned.

The clothing had long since rotted away. The only adornment I saw on the skeleton was a small crucifix with the corpus gone which seemed to be silver and was about an inch and half by an inch in size. There was also a small shell button with four tiny holes in it such as would be worn on a shirt or underwear. Father Kieran said that the cross was probably placed on Kino when he was buried. Kino had come from Dolores, fifteen miles east of Magdalena, to bless the new chapel of St. Francis. The trip, from his point of view, was short and he evidently [90] did not plan to be long because he brought very few of his personal things. After the dedication on March 15, 1711, Kino became very ill and died that night. He was buried the next morning and obviously there was no time to send to Dolores for adornments for the burial. In addition, the priest in charge of St. Francis, Reverend Augustin Campos, S.J., had only three sets of vestments. Since five are needed for the liturgical year, it was doubtful if he used one of his precious cassocks to bury even such a great friend and man as Father Kino.

The discovery of Father Kino's bones came about, unfortunately, when one of the workmen put his pick through Kino's skull. The hole, which shattered a portion of the skull, was on the forehead, just above the right eye. The skull rolled out on the bottom of the excavation and at that point the experts were not sure it was Kino's remains. As more evidence developed, however, they became certain but removed the skull from the rest of the skeleton. Mexican anthropologists have a rule in such a case that prevents the removal of the remains because this in some ways could effect the authenticity of the find. But since the skull had been inadvertently removed, it could be taken elsewhere for examination. The skull showed that Kino evidently had a long, prominent nose, and a high forehead, and as Dr. Romano remarked, it was that of "a person of great masculinity."

Father Campos buried Kino under the gospel side of the altar. The chapel was so small there was only one altar. Father Kino's head was toward the altar and his feet were to the south and back of the church. This little chapel, approximately twenty by forty feet, was the only church in Magdalena. There was a large mission church at San Ignacio ― built by Kino ― three of four miles north of Magdalena on the Rio Magdalena. The little town of Magdalena was a Pima village with no Europeans living in it, other than the missionaries.

On Sunday evening, my youngest son, Rickey, and I were privileged to sit with the experts at the Central Restaurant across from the present Magdalena church near the plaza. As these men discussed the findings ― after swearing Rick and myself to secrecy ― it was apparent they had little doubt that Father Kino's bones had been found. Each man commands great respect in his field and their decision was arrived at carefully [91] and painstakingly, using the benefit of their many years of education and experience.

For example, a question arose as to whether a particular type of building foundation was "Jesuit" or "Franciscan." In one case only mud and rock were used; in the other lime was added. To be certain they would recognize a "Jesuit" foundation, especially one built by Kino or under his supervision, the experts went to Dolores Mission and dug up one of Father Kino's buildings to see exactly how it was constructed.

Mayor Nava and the city had gone all out to help the men. Headquarters for the expedition was in a large room on the main floor of the municipal building. In addition, I met two local historians who were quite conversant with Kino history and were of great help. These were Señors Donadieu and Sanchez de la Vega.

Father Kino's remains were found less than ten feet from the windows of the expedition headquarters. The dig had actually started near the present church and was centered to a large extent between the plaza and the city hall. The streets in that area looked like trenches dug for a war. Part of the municipal building had been dug in and around, as was the jail. Several old footings were found: one, an old three room school built by the Franciscans in post-Kino days; another was for a church which Father Campos had later built; and, of course, the main footings and foundations of St. Francis Chapel where Father Kino's bones were found.

About a year after Father Kino died, Father Campos brought from Tubutama the bones of two Jesuits, Manuel Gonzalez, S.J., and Ignacio Iturmendi, S.J., and reburied them at St. Francis chapel. The burial records describe how the bones of these Fathers were buried in small boxes next to Kino. Father Iturmendi was buried on the right side of Father Kino and Father Gonzalez on the left. The bones were found on each side of Kino although the boxes were long since gone. All the burial records were proven as to where various people were buried in relation to the physical parts of the church.

Other items mentioned in Father Campos' burial register were discovered. Children were buried in the church, evidently as "little angels" honoring Father Kino; and a burial was found right outside the chapel door. [92]

Kino's remains were under the lawn of the city hall. The beautiful grass and trees were well watered and the experts said that over the years, as the watering went on, chemicals went down into the soil, destroying clothing and wood. A large board had protected the crucifix and the little bone button while other items and clothing had long since disappeared.

One difficulty causing some problems was that for 100 years after Kino's death, this entire area had been used as a burial ground. The current expedition showed that at various times and for various reasons people had dug through the footings of old buildings, but had not recognized them as such. This would be very easy to do because I could not recognize hunks of mud and rock as footings. Once uncovered, however, and the plat of the building laid out, it was easy to see. At one place the diggers excitedly followed what they thought were footings and foundations, only to find that someone had a long pit to fill and followed the natural inclination of first filling it with rocks and then dumping in whatever soil was around. The ground underneath and around the plaza is very rocky and sandy.

Many illustrations were used to help locate the buildings and footings. Over the past century or so, various persons, such as J. Ross Browne, had passed through and made sketches of the town. These helped the experts to determine what was on the surface of the ground at a given time. Also, they showed that the present church was not Jesuit and as Father Kieran said, "was hardly a Franciscan church." For the most part it had been built by the secular clergy. Evidently as time went on the need for the little chapel of St. Francis was not great and after falling into disuse, it disintegrated, With its disappearance the knowledge of where Father Kino had been buried was lost. The burial records of the chapel found their way to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, and the experts were working with photostatic copies made of the entries in Father Campos' handwriting.

When it became apparent that the grave of Father Kino had been found, a veil of secrecy was dropped on all activities by the Mexican government. The area was roped off and armed guards prevented the public from entering. The next morning I had the opportunity to roam all over the dig, examine the ruins, follow the footings. and watch the [93] quiet excitement and drama as proof became more absolute that this was Father Kino's grave. We were asked not to photograph the bones but we could photograph the rest of the activities.

Dr. Olvera said many places claim to have the bones of Kino: San Ignacio, Tubutama, plus many other small Mexican villages in the area, to say nothing of San Diego, California, New Mexico and Rome. No doubt many loyal Sonorans will always believe Kino is buried in their particular town under the altar of one of the many missions Kino built in the Pimería Alta.

On Monday evening, May 23rd, Father Kieran and I called upon Archbishop Juan Navarrete in Hermosillo to tell him of the finding. This announcement was made to the Archbishop at the request of the experts. Their rule of secrecy with me had to do with any announcements being made "officially" to newspapers in the United States. The Mexican Government planned their own announcement and the American announcement could follow. It was certainly interesting to watch the Archbishop's reaction. A man of between 70 and 80 years, he has always lived under Kino's cloud and has been a very avid Kino supporter. He asked many searching questions, and after a cross-examination of about an hour, was satisfied Father Kino's remains had been found. He laughed over what he called Kino's "Italian nose" and seemed very relieved and happy over the finding. The Archbishop said he had always been certain Father Kino was buried in Magdalena and he listened with great delight to where the grave is. He described various attempts to locate the grave which had been made in the past.

The search for Kino's burial place was successful this time because of the strong backing by the Mexican Government, which furnished funds and brainpower to get the job done. In addition to this, the Mexican Government was wise enough to bring in the two American experts who worked hand-in-glove with the Mexicans. A great deal of this activity was stirred up by the placing of Kino's statue in the Statuary Hall at Washington, D.C., by the State of Arizona. The President of Mexico was quite impressed by the Arizona ceremony and from this deduced that finding of Kino's remains would be of value to Mexico for many reasons. So, when the President "blew the bugle and raised the flag," things got underway, and successfully so. Many of the past [94] attempts failed, not for lack of zeal, but for lack of historical, anthropological, and archaeological information. The Mexican Government intends now to build a monument over Father Kino's bones and not to remove them from the place where found.

Although I had no official connection in any manner with the search, I was invited there by the Mexican Government and I wish to thank them for the courtesy, kindness, and knowledge that was offered me.

James M. Murphy

President

Arizona Pioneer Historical Society

Summer 1966

Historical Roundup

A Gathering of News and Notes about the Society and Activities of Historical Interest

The Journal of Arizona History

Kino's Arthritis Predates Industrial Revolution

Email concerning Kino's arthritis

From: John F. Carroll, M.D.

To: Mark O'Hare

Date: Sat 5/21/2016, 9:14 AM

"Mark, we hope to attend Saturday the Kino Symposium. …. You indicated that you wanted my affidavit of Prof. William O’Brien’s viewing of his [Kino's] skeleton, so here it is.

Bill O’Brien was a classmate at Yale Medical School, and became Professor of Medicine at The University of Virginia Medical School. He was trained in Internal Medicine and rheumatology (diseases of the joints). In 1966, I received a call from him that he was in Tucson to attend a medical meeting. I joined him at the meeting, and he informed me there that the meeting attendance was so that he could go to Magdalena Mexico to view the bones of Fr. Kino which had recently been discovered. His interest was that Fr. Kino’s death date was known to be before mid-18th century, and he was said to have suffered from severe arthritis during his lifetime. Dr. O’Brien felt that rheumatoid arthritis did not exist before the middle of the 18th century and might be caused by some by-product of the industrial revolution, or some evolutionary change in a virus or bacterium. He examined Fr. Kino’s skeleton and found only traumatic arthritis, no evidence of rheumatoid arthritis. …

John "

Editor's Note: Dr. Carroll's classmate was Dr. William M. O'Brien, M.D. (1931-2014). Dr. O'Brien was an expert in the study and treatment of rheumatic diseases. He was the author of 90 scientific papers and contributed chapter articles in 10 medical books during his academic career.

The International Team That Found Kino's Grave

Senator Barry M. Goldwater

Introduction

Father Kino in Arizona

I was pleased, as the junior United States Senator, to introduce in the Senate, with the support of our Congressional delegation, House Joint Resolution No. 439, which on August 24, 1962 authorized and granted to Arizona the privilege of placing the Kino statue in the national Capitol. Supported by voluntary contributions and working tirelessly, the Committee achieved its purposes. On February 14, 1965, the Kino statue was unveiled under the Rotunda in solemn ceremonies that attracted Mexican and American officials, church dignitaries, historians, members of the Kino family, and prominent public officials.

Publicity surrounding the Kino statue effort in Arizona stimulated new attention to Kino below the Mexican border. For many years there had been a curious interest in locating the chapel in Magdalena, Sonora, in which Father Agustin Campos reported that he had buried Father Kino following his death on March 15, 1711. As early as 1928 Dean Lockwood had made preliminary explorations in Magdalena in an effort to locate the chapel of San Francisco Xavier which Kino had dedicated only hours before his death. Mexican scholars in following years uncovered many old foundations in the town, but none of their excavations yielded confirmation as being the burial place of Father Kino or fitted descriptions of the chapel. The Lions' Club of Magdalena, as a civic effort, had supported some such explorations. Among Mexican savants remembered for such efforts were Professor Serapio Davila, Professor Eduardo E. Villa, Professor Fernando Pesqueira, and Senor Ruben Parodi. Their work, although not directly successful, helped to narrow the area of exploration for later, effective archeological studies.

The unveiling of the Kino statue in Washington came at a time when the Republic of Mexico was projecting plans for the Olympic Games which are to be held in our neighboring land in 1968. In Mexico City federal officials responded to the suggestion from Professor Wigberto Jimenez Moreno, historian on the staff of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, that Father Kino might evolve as northern Mexico's most stirring historical and tourist attraction. By the end of July of 1965 instructions had been issued that sent a team of technical experts to Sonora for the purpose of "locating the remains of Father Kino, and, in that eventuality, of proving their authenticity." Dr. Eusebio Davalos Hurtado, director of the National Institute, |13| assigned Professor Jimenez Moreno and Professor Jorge Olvera, who had been trained at Santa Clara University as an architect and archeologist, to the task. In Sonora they enlisted generous support and assistance through the keen interest shown in the endeavor by Governor Luis Encinas.

The weeks of August and September of 1965 were spent by the team in explorations in several parts of Magdalena, including a so called chapel site which, upon excavation, was revealed by details of construction to be of the Franciscan period, possibly a century following the death of Kino. Excavations during this period were extended into the public plaza of Magdalena, between the extant church and the Municipal Palace. A number of foundations were uncovered, but none completely fitted the pattern outlined in Father Campos' description of the chapel which had become the sepulcher for Father Kino. In late September, at the season when Papago Indians and other Catholic faithful in Pimería Alta make an annual pilgrimage to Magdalena to celebrate the birthday of San Francisco Xavier, work was suspended.

It was resumed in April of 1966, but not until important developments had taken place. In the previous summer's work the Mexican team had been assisted by Dr. William Wasley, State Archeologist attached to the Arizona State Museum at the University of Arizona. Dr. Wasley also had been consulted some years before on earlier excavations at Magdalena, at one time revealing that explorations were being made in material and fill laid down much later than the Kino period. Aside from being an experienced, well-trained archeologist, Dr. Wasley had the added attribute of being bilingual, which is a definite asset when, as in the case at Magdalena, much of the labor was being provided voluntarily by local residents.

Before the work resumed Professor Jimenez Moreno and his team also had enlisted the services of another American, Father Kieran McCarty, O.F.M., Catholic priest and Franciscan historian of Old Mission San Xavier del Bac near Tucson. We at the Arizona Historical Foundation had worked closely with Father Kieran and helped support his studies of the archival records of Sonora. He had written the introduction to one of the books published by the Foundation, "Lancers for the King." For more than a year Father Kieran had been serving as pastor for a chain of small Catholic churches along the Altar River. His headquarters was at Altar, with subordinate churches at Tubutama, Oquitoa, and Saric. Thus his pastorate was the Kino country. Father Kieran is a historian, assigned to the Southwestern field by the Academy of Franciscan History in Washington, D. C., and he has been working extensively in public and church archives on a history of the Franciscan period which began in Pimería Alta with the Jesuit Expulsion of 1767. Thus he already knew the church history of the Magdalena area, and like his friend Dr. Wasley, was entirely at ease in both Spanish and English. Furthermore, Father Kieran was thoroughly familiar with the holdings of the Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society in Tucson, he was acquainted with Kino traditions and burial records both in Mexico and those collected in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, and in his research had drawn upon church archives in Rome for additional material.

The Mexican team of experts had been augmented as well. Senor Gabriel Sanchez de la Vega, a public health officer in the Magdalena area, had developed a strong interest in Father Kino; Senor Agustin Yanez of the Secretariat of Public Education represented that agency; Professor Arturo Romano, a physical anthropologist with the National Institute, joined the party; Father J. Cruz Acuna represented the Archdiocese of Hermosillo; Professor Pesqueira represented the State of Sonora once more; while the project was conducted under the direction of Professors Jimenez Moreno and Olvera.

Excavations resumed on April 19 with certain facts forming a hypothesis of what should be found: Father Campos had written in the burial book of Magdalena, which was taken to California in 1879 by Alphonse Pinart, a French traveler and historian, that Kino was buried on March 16, 1711 on the Gospel (i.e., the left) side of the altar in the new chapel, between the second and third vaults. A year later Campos had buried beside Kino the bones of two other Jesuit priests, Fathers Manuel Gonzalez and Ignacio Iturmendi. Since these were reburials, the bones were in small boxes and would not be found recumbent as the bones of Kino should be revealed. The chapel was not to be confused with a nearby church started in 1705 and known to have been in ruins by 1772. When J. Ross Browne had visited Magdalena in 1864 he had sketched the area being excavated, showing the existing church (which was dedicated in 1832), as well as an older church, Santa María Magdalena, which evidently was leveled when the railroad was built through the town in 1882. He also showed a parish house, which has long since disappeared. From historical fragments collected by Father Kieran, it was considered possible that the Kino chapel would be behind or to the north of the older church. Looming large over the site was the Municipal Palace, consisting of the city hall, jail, and a bell tower, built about 1910 over the foundations and ruins of earlier structures. Fitting into the developing hypothesis were other facts, such as the burial of other individuals, adults and children, near and within the chapel. A sketch made by Pinart suggested the orientation of the old chapel with the new church.

An official publication of the chronology and details of the exciting discovery to be prepared by the Mexican government will provide full details and photographic progress of the expedition. On May 21, 1966 it was established with little or no question of doubt that Father Kino's remains had been found. The hypothesis developed by Professor Jimenez Moreno in collaboration with Father Kieran had worked out, step by step and detail by detail.

The importance of the discovery is yet to be fully evaluated. The Mexican federal government and the State of Sonora have expressed interest in reconstructing the chapel and providing there a permanent sarcophagus to preserve the remains of Father Kino. Unquestionably Magdalena shall take on new importance in the economy of northern Mexico as the shrine of the Apostle to the Pimas. Historians in both Arizona and Mexico feel that it is of major importance, confirming as it does the authenticity of Father Campos' account of Kino's last hours, and once more giving strength to documentary evidence in reconstructing and understanding history. As Pimería Alta is a geographical area reaching into two nations, it is also significant that the chapel where Kino was buried should have been discovered in an effort that found historians and scientists of the two nations joining hands in a common goal. It was truly international cooperation of a spirited and encouraging kind.

September 1966

Barry M. Goldwater

Introduction

Father Kino In Arizona 1966

To download entire Introduction

Click

Goldwater Introduction

Discovery Team

Historical Research & Archaeological Excavation

The team that discovered Kino remains coordinated the search in distant archives with archaeological excavations mainly in the town of Magdalena, Sonora. The team included Professor Wiberto Jimenez Moreno, Head of Historical Research of I.N.A.H., ethnohistorian and Kino discovery project leader; Professor Jorge Olvera H., art historian and ethnohistorian, I.N.A.H.; Professor Arturo Romano Pacheco, Head of the Department of Physical Anthropology, I.N.A.H., physical anthropologist and archaeologist; Dr. William W. Wasley, archaeologist, Arizona State Museum, the University of Arizona, Tucson; Rev. Kieran R. McCarty, O.P.M., Franciscan historian; Rev. Cruz G. Acuna, historian from Sonora; Professor Fernando Pesqueira, Director of the Sonora State Museum, Hermosillo, and historian; chemist Gabriel Sanchez de la Vega of Magdalena, Sonora; Conrado Gallegos, topographer of the General Office of Public Works of the State of Sonora; and Professor Jorge Angulo, archaeologist, I.N.A.H.

Material Analysis Team

After the remains of Father Kino were discovered, the archaeological materials found during the excavations were taken to the University of Arizona in Tucson for analysis. Wiberto Jimenez Moreno, Director of the Department of Historical Research, I.N.A.H. and Kino discovery project leader, coordinated the work of the different specialists. The analyses were undertaken by Jorge Olvera H. of I.N.A.H. From the University of Arizona the team included: Dr. Bernard L. Fontana, ethnologist in the Arizona State Museum and lecturer in anthropology; Dr. Charles W. Ferguson, Professor of Dendrochronology, Laboratory of Tree Ring Research; Dr. Peter E. Pickens, Department of Biological Sciences; Dr. Emil W. Haury, Department of Anthropology; Walter B. Miller, Department of Biological Sciences; Mrs. Joanna Bouchard, a student in the Department of Anthropology; Dr. Walter H. Birkby, physical anthropologist in the Arizona State Museum and a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology; Robert G. Baker, Chief Curator, Arizona State Museum and lecturer in the Department of Anthropology; Robert T. O'Haire, adjunct Professor of Mineralogy, Arizona Bureau of Mines; and J. Cameron Greenleaf, Highway Salvage Archaeologist, Arizona State Museum.

1987 Account of Dr. Wigberto Jiménez Moreno

Dr. Wigberto Jiménez Moreno

"El fruto del esfuerzo"

in "El encuentro de los restos del padre Kino"

Publicaciones del Comité del Trecentario del Arribo de Eusebio Francisco Kino a Sonora (1687-1987), Hermosillo, 1987

Pinart Exhibits Kino Burial Record on European Tour

Some sacramental registers ended up in private collections after they had been purloined. One example is sacramental registers from several parish archives in northern Sonora, now in the Pinart collection of the Bancroft Library at the University of California Berkeley. Hubert H. Bancroft (1832–1918) hired Alphonse Pinart (1852–1911) in the late 1870s to collect documents from northern Mexico.

Pinart visited the parish archive of the former Jesuit mission community of Santa María Magdalena located in northern Sonora, and purloined baptismal, marriage, and burial registers. He was particularly interested in the 1711 death record of Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645–1711), who established a number of missions in northern Sonora. Pinart later exhibited the Kino death record on tour in Europe.

Robert H. Jackson

To Educate and Evangelize:

The Historiography of the Society of Jesus in Colonial Spanish America

Jesuit Historiography Online 2018

To Go To Kino Grave Discovery Chapel (page 2), click

Grave Discovery Chapel Page

To Go Kino Grave Discovery Olvera Account (page 3), click

Grave Discovery Olvera Account Page

Kino Last Letter in the Historical Record Before His Death

Father Rector Juan María de Salvatierra gives me to understand that by disposition of our Father General my principal obligation is to succor California, and I am now sending thither also a goodly quantity of provisions and cattle, which is what they are asking of me.

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Letter to Juan de Yturberoaga

Procurator for Jesuit Province

Letter dated December 7, 1710