Kino - Missionary Father

Among the few known methodological texts that provide insights into missionary practices characteristic of this movement is Book Eight of Kino's "Vida del F. X. Saeta." In it Kino stressed that for the missionary to excel in conversion, he must nurture the virtue of patience and tolerance.

From the text, its is clear the Kino admonished the missionary that preached from a position of authority, but rather advised that the missionary should work to maintain closed personal contact with the Natives, often sitting among them on the dirt floor or on a rock.

Eric A. Schroeder

"Hegemony and Mission Practices in Colonial New Spain"

in "Evangelization and Cultural Conflict in Colonial Mexico" 2014

No simple hagiography, the "Life of Javier Saeta" was a passionate defense of the Pimería Alta mission that listed Spanish errors and defended Pima innocence in the face of abuse. Through historical evidence the missionary identified the material causes behind not only Saeta's murder, but also the wider violence that led to the Pima Revolt of 1695, including the indiscriminate massacre of 48 Pimas at El Tupo. Thus the missionary not only modeled careful scholarship, but also intercultural understanding and social justice.

Dr. Brandon Bayne

Recalling Kino: Remembering a Pimería Past, Reimanging an Arizona Present

SMRC Revista Winter 2010

To view Brandon Bayne’s dissertation “A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 – 1767”, click

https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367448

The grandeurs, the glories, the crowns and the kingdom of heaven have been especially prepared for the poor, the destitute, the abandoned, the insignificant, and those little esteemed in this life. But the greatness of new missions will shine not only in the eternity of heaven, but also in the most desolate and remote regions of the world.

Eusebio Francisco Kino

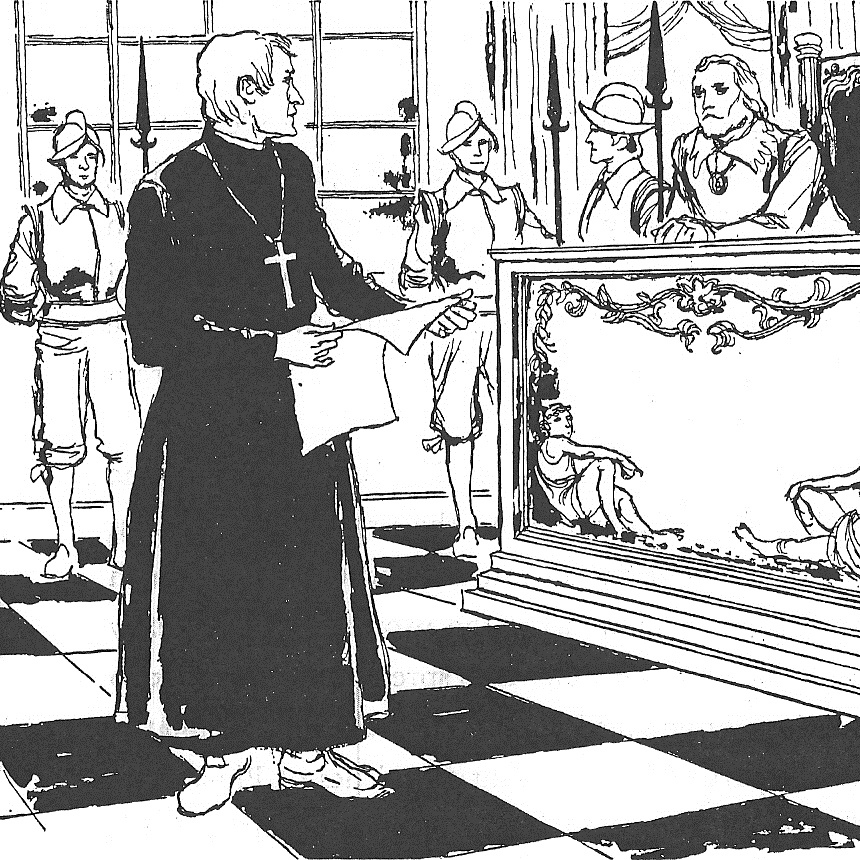

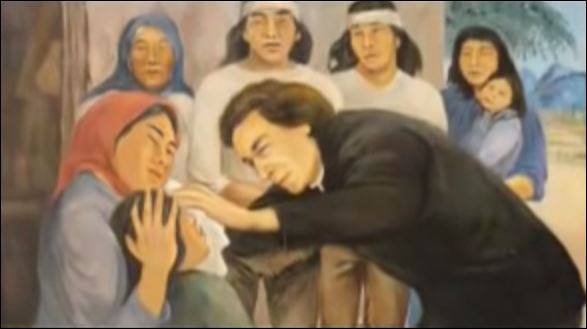

Kino Defending O'odham People Before Viceroy of New Spain

Missionary Kino

"Cycles of Conquest"

Edward H. Spicer

Kino began the work of missionization of the Upper Pimas [O'odham] and thus had the advantage of a long period of almost singlehanded building of social relationships between them and the Spaniards of the region. He built his own personality into these relationships.

Typical of Kino's finding of good will on the part of the Pimas wherever he went is the statement in a letter of 1687 describing his first tour of duty: "In all places they received with love the word of God for the sake of their eternal salvation." But this was not merely an expression of first enthusiasm in a new task, for in the following year he was even more enthusiastic: "God willing, hundreds, and later thousands will be gathered into the bosom of our sweet, most holy Mother Church, for about five thousand of the neighboring Indians have come asking at this time with most ardent pleading for holy baptism. They envy the happy lot of those in the three new settlements."

And again five years after the first, of a visit to the Sobaipuris on the San Pedro River, he wrote "Captain Coro and the rest of them received me with all kindness." Two years later of a trip to the Gila Pimas, he wrote: "All were affable and docile people." In 1696 with nearly ten years of missionary work behind him and after previous visits to and work with the Sobaipuris of the Santa Cruz Valley, he wrote that at Bac he was "received with all love by the many inhabitants of the great ranchería and by many other principal men, who had gathered from various parts adjacent."

In 1698 he again wrote after a trip through the whole Papago country that he was "grateful for the great affability and cheerfulness of everybody whom we met." And so it went throughout his life until he died in Pima country at Magdalena. Wherever he went, according to his accounts, among Pimas or Yumans, his reception was warm and hearty and he came away with feelings of great friendliness. He apparently was able to charm and to be charmed by all the Indians, whether on first visits or in the missions where they knew him well.

At the bottom of Kino's pleasant and easy relations with the Indians seems to have been a tolerant spirit. Not only has he left no record whatever of suppression of Indian ceremony, but in his writings there is no particular concern with Indian ways as evil. He does not inveigh against drunkenness, which was a common ceremonial practice among the Upper Pimas, as it was among the Tarahumaras. He spends no words on condemnation even of Pima witches.

One would think that somehow he managed to remain blandly unaware of the existence of Indian ceremonial life away from the missions, if it were not for the fact that there are accounts of all-night dances and other ceremonies which took place at villages where be spent the night or visited for a period. Many such all-night gatherings with dances and music he evidently felt honored by, believing (probably correctly in some instances) that they were given in his honor.

Moreover, he gives a one-paragraph account of a scalp dance among the Sobaipuris, saying: "We found the Pima natives of Quiburi very jovial and friendly. They were dancing over the scalps and the spoils of fifteen enemies, Hocomes and Janos; whom they had killed a few days before. This was so pleasing to us that Captain …. Bernal, the Alferez, the Sergeant and many others entered the circle and danced merrily in company with the natives." This of course was a situation in which the Spaniards were delighted to celebrate a victory over mutual enemies, the eastern tribes associated with the Apaches, but it is also characteristic of the pleasant and noncritical way in which Kino took note of and sat in the midst of so many native ceremonials.

He almost never permitted himself to be even mildly critical of native practices, if indeed it actually bothered him. Such tolerance must have made him welcome everywhere and caused him to be viewed only as a constructive bringer of new good tidings and never as one who was prepared to destroy what the people already had.

There was also a certain amount of give and take in his relations with the headmen of the many Pima villages which he visited. Repeatedly he describes how he sat and talked for hours in such villages. What he said must have had a great deal of interest; an example is the following - describing his visit to Bac in 1692 - which shows his teaching methods very clearly:

"I spoke to them of the word of God, and on the map of the world I showed them the lands, the rivers, and the seas over which we fathers had come from afar to bring them the saving knowledge of our Holy Faith. I told them also how in ancient times the Spaniards were not Christian, how Santiago came to teach them the faith, and how the first fourteen years he was able to baptize only a few, because of which the Holy Apostle was discouraged, but that the Holy Virgin appeared to him and consoled him, promising that the Spaniards would convert the rest of the people of the world. "

"And I showed them on the map of the world how the Spaniards and the Faith had come by sea to Vera Cruz and had gone into Puebla and to Mexico, Guadalajara, Sinaloa, Sonora and now to ... Dolores del Cosari, in the land of the Pimas ... that they could go and see it all, and even ask at once their relatives, my servants, who were with me. They listened with pleasure to these and other talks concerning God, heaven, and hell, told me that they wished to be Christians, and gave me some infants to baptize."

This was, of course, the general method of teaching and preaching of the Jesuits. Certainly Kino was merely one of many capable missionary teachers who knew how to employ concrete demonstration, in this case maps and charts, and to spice the doctrine with history, and even to meet the skeptics with reference to Christianized Indians who could be questioned right there in their own tongue about it all. These merely show that Kino was capable in the missionary teaching tradition.

His special genius was his capacity to sit down immediately afterwards and listen to the Pima headmen. Over and over again in his accounts, he tells how he was invited to sit through a night or even two days and nights in which be must have done as much listening as talking, Thus in 1700 on one of his trips among the Yumas, he was persuaded to stay, even though he had wanted to push on, because people wished to hear him. He preached in his usual way. Then, he says, "These talks, ours and theirs, lasted almost the whole afternoon and afterward till midnight, with very great pleasure to all." He was not annoyed by having been put off schedule; rather he relaxed and enjoyed a day of mutual give and take.

How much he understood, even though he always had interpreters with him, we shall never know, nor are we sure of his attitude about the content of the long talks of the Indian spokesmen. He never mentions the content unless it had some direct bearing on his mapping interests or the building of the mission chain. But at any rate he behaved in a way, at very great cost in time, which was regarded as courteous and must have made him a delightful guest. He behaved in this respect. in fact, in the way that any visiting headman among the Indians was expected to behave. Long talks by all parties were the rule, but they must not be one-sided - and this Kino seemed instinctively to understand.

Another of Kino's qualities, which was not by any means unique among the missionaries, but most abundantly developed in him, was that of organizing ability. He believed in gathering people together for particular and dramatic purposes. He showed his ability for this when Chief Coxi was baptized at Dolores shortly after the founding of that mission. Kino made it the occasion for inviting other Pima headmen from far to the west where he had made a beginning at contacts and five attended. He also brought "Spanish gentlemen" from the mining town of Bacanuche to the ceremony.

This sort of thing he continued to do on a grander scale as time went on. He brought hundreds of people from all over the Upper Pima country to the dedication of the church when it was finished at Dolores. He brought a large group of Pima headmen from the Santa Cruz and San Pedro valleys and elsewhere to Dolores and then had them go on a pilgrimage through the northern Opata country to have an audience with the Father Visitor at Bacerac and ask for missionaries to be sent to their villages.

He called meetings at Bac and other Pima villages to discuss his interest in the problem of whether California was an island or not. His accounts indicate that he got great responses in such meetings and that he participated in the discussions rather than addressed the groups. He had some sort of genius for getting people to do things together and this must have been an important factor in establishing communication among Upper Pimas who had been isolated from one another before.

It would seem, however, that it was Kino's personal characteristics - his enthusiasm, his warmth of feeling for individuals such as Captain Coro, Coxi, and others with whom he became associated, his tolerance of ways not in accord with European, his delight in big and ceremonial gatherings - rather than any inclination or ability to understand other ways and reconcile them that lay at the bottom of his successes in the Pima country.

Edward H. Spicer

The Spanish Program

"Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest 1533-1960" 1962

Pages 315 - 317

To download excerpt about Kino's missionary work, click

Missionary Kino - Spicer document (text)

Padre Kino's Missionary Teaching

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

In working on the history of the Society of Jesus and especially its early missions, I have learned that its missionaries were not preoccupied with questions of orthodoxy and refinements of the Magisterium. They were much more radical; they were really doing what Christ asked us to do - that is, to teach the Way, to teach Christian living. They were not worried about making certain that their neophytes were doctrinally precise. As a matter of fact most converts had no clue about what they were being taught-at least in the beginning.

These observations compel one to become critical about what the mission of a missionary is, what the mission of the Church is, what the mission that Christ has given is - to those who were to follow Him and teach as He did. When I look at the life of Padre Kino and the other missionaries with him, this is precisely what I see. .... For Saint John, it was not a question of what they thought; it was a question of what they did. It was a question of interpersonal conduct. It was a question of outreach in a sense of giving, in a sense of community, in a sense of sharing. In fact, in the earliest days of the Church, its members were not known as "Christians," but as "Followers of the Way." ....

Put yourselves in the shoes, boots perhaps, of a man like Padre Kino, who was young, vital, and a dreamer of almost impossible dreams, somewhat like Don Quixote - well, not exactly, because Kino came from the Italian Tyrol and not La Mancha. ....

[T]he task of the missionary was not, and is not, that of communicating knowledge alone. The missionary's task is one of sharing knowledge, the basic appraisal of nature, and the fundamental appreciation of peoples, their interaction, and their relationships. A "metanoia" is an interchange, a complete transformation of the person. When we look at the teachings of the Church, when we review the paradigms of doctrine, they are only valid as metaphors that reinforce, that communicate some richer, higher notion to people who are on a quest for truth, understanding, and ultimately love. …..

That is the faith we find in Padre Kino. This is why I titled this essay, "Kino: On People and Places." I could have recounted his expeditions, his mapmaking, his church-building, with an impressive array of historical statistics. One might then have misunderstood in thinking he came to do these things. No, Kino came to all these places and recorded them because of people. And in finding people in the places he visited and explored and in doing the brave things he did, he found God. He found God in the people he served, and together they joined in the quest of the re-creation of the world, which we like to call salvation.

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

"Kino: On People and Places"

In "The Jesuit Tradition in Education and Missions: A 450 Year Perspective" 1993

To download Kino's missionary teaching's, click

Missionary Kino - Polzer document (text)

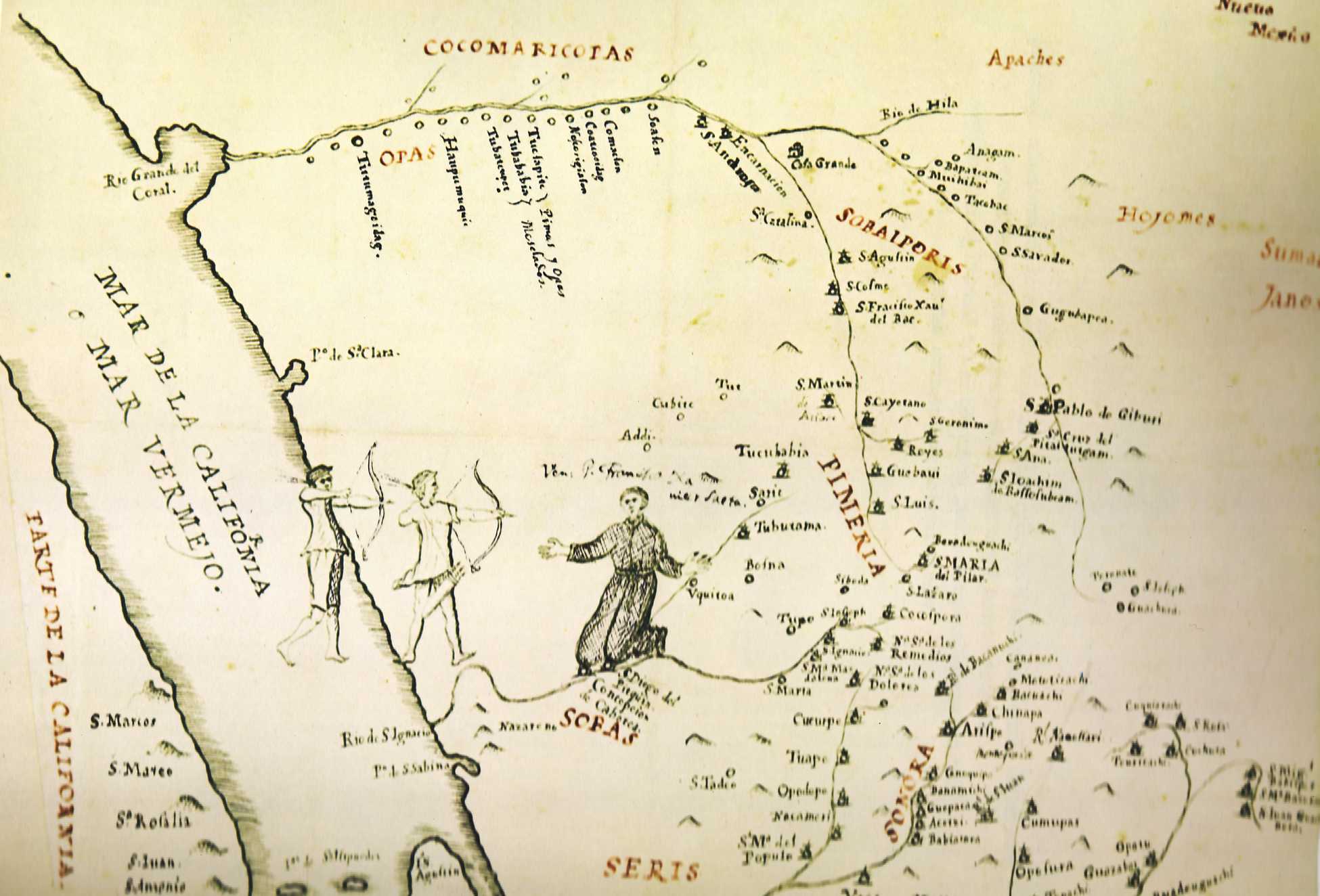

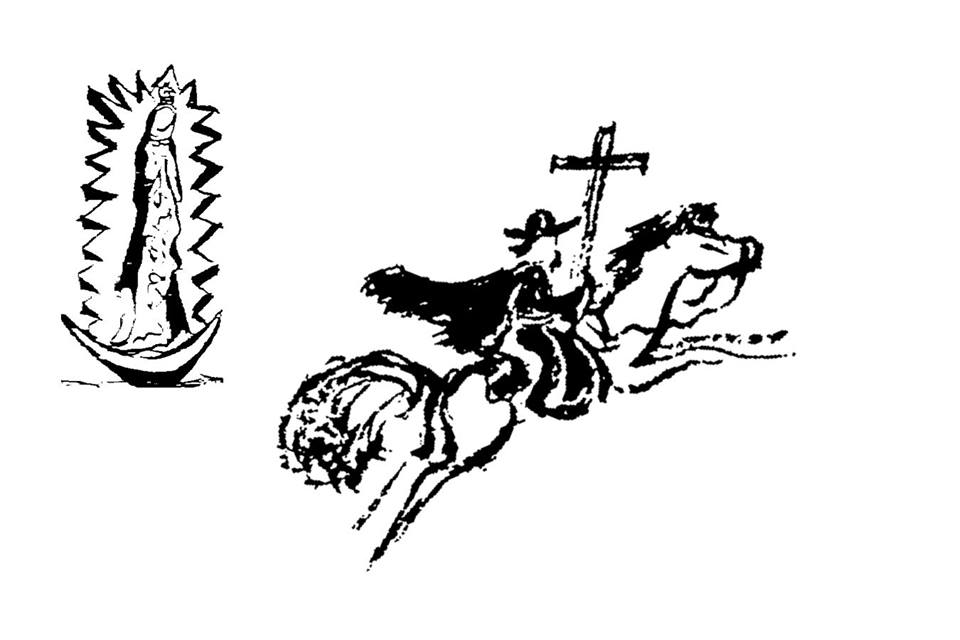

Kino's Hand-drawn Map of the Pimeria Alta Was Part of His Saeta Biography

"Kino Biography's of Father Saeta, S.J."

"Vida del P. Francisco J. Saeta, S.J. - Sangre Misionera En Sonora"

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Online in English and Spanish

"Kino Biography's of Father Saeta, S.J." 1971

by Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1696

Original Spanish text translated and edited by Dr. Ernest J. Burrus, S.J. with introduction and notes

Epilogue by Charles W. Polzer, S.J

For text of entire book, click

Kino Saeta Biography doucument (pdf)

Kino Saeta Biography document (text)

For Kino Saeta Biography Footnotes, click

Kino Saeta Biography Footnotes document (pdf)

Kino Saeta Biography Footnotes document (text)

"Vida del P. Francisco J. Saeta, S.J. - Sangre Misionera En Sonora"

by Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J 1696 (1961)

Orginal Spanish text translated and edited by Dr. Ernest J. Burrus, S.J with introduction in Spanish and English.

For digitized copy by Princeton Theological Seminary Library, click

https://commons.ptsem.edu/id/vidadelpfrancisc00kino

Historical Background

"Kino's Biography of Francisco Javier Saeta"

Editor Note

Padre Kino organized a peace conference between the Native People and the Spanish military in August 1695 that ended six months of warfare in the Altar Valley. In the following 2 months Kino wrote a book about the life of martyred Father Saeta who was killed at the mission of Caborca on Holy Saturday in the beginning hours of the violence. The book is now referred to as "Kino's Biography of Francisco Javier Saeta" and provides a very early description of modern missionary methods.

The purpose of the book was to explain why the violence erupted so that the Native People would be protected from any further reprisals based on false rumors circulated by powerful interests who coveted the mission lands and Native labor.

The book describes the life of the Father Saeta, a young Italian missionary, and the events surrounding his death. Also the book contains Padre Kino's missiology or philosophy about conducting missionary work. Although Father Saeta served as a missionary for only six months, Kino presents his own philosophy as if it they were Saeta's opinions by constantly writing "Father Saeta used to say."

The book was used as part of Kino's defense of his beloved Native People and his own missionary career against the powerful interests who opposed him . After riding 1,500 miles in seven weeks from his mission headquarters to Mexico City, Kino appeared in January 1696 before the highest of officials and successfully advocated for his return to the Pimería Alta.

After Kino returned to the missions, his work was further supported by the head of the Jesuit order, Father General Gonzales, who wrote from Rome to Kino's New World superior "I am convinced that Kino is a chosen instrument of Our Lord for His cause in those missions."

Writing throught the book about the causes of the violence, Kino concludes:

"[The] cause that has contributed to these deaths, riots and outbreaks has been the constant opposition to the Pimas which in turn has been founded on sinister suspicions and false testimony as well as on rash judgments because of which many unjust killings have been perpetrated in various parts of the Pimeria. ... The Pimas have been viciously and unjustly blamed for the thefts of the livestock and the plunder of the frontiers. ....it is evident that the treatment of the natives in the Pimeria has been very unjust — leading as it has to mistreatment, torture and murder."

To view and download historical background of the Saeta Biography, click

Saeta Biography Background History - Polzer document (text)

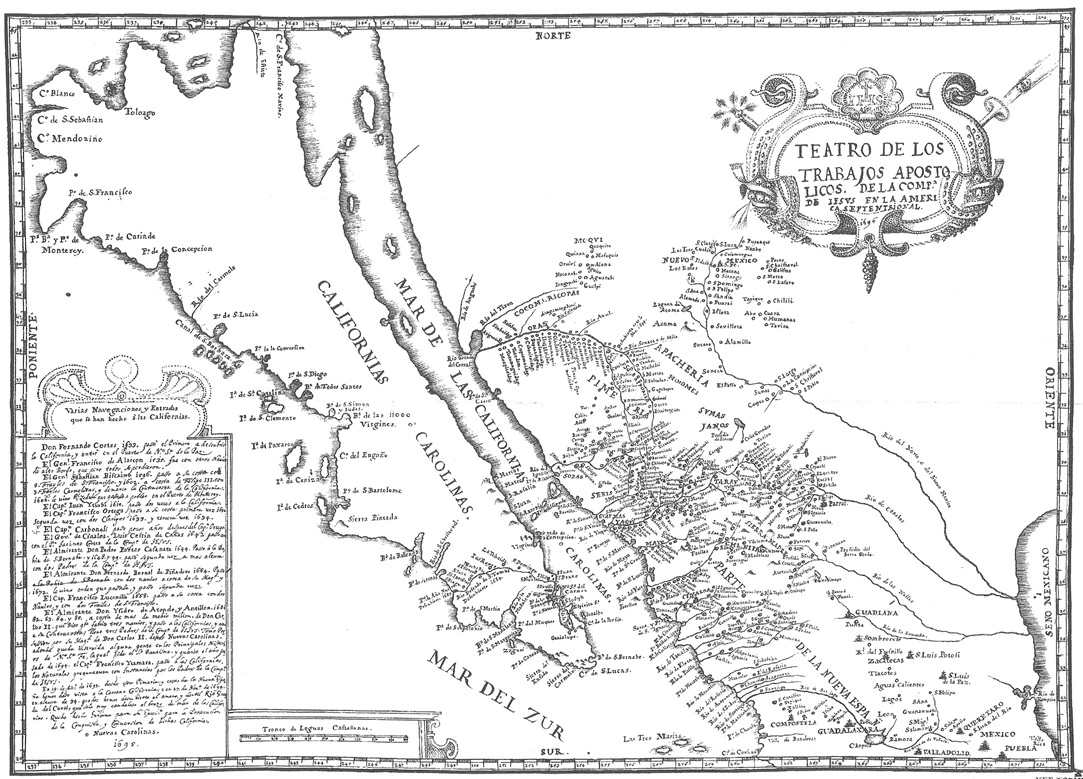

"Teatro de Los Trabajos"

Kino's Map with His Biography of Saeta

Introduction

"Kino's Biography of Francisco J. Saeta, S.J."

Ernest J. Burrus

Summary and Synopsis

The reader finds in Kino's monograph on Saeta both less than the term "life" or "biography" indicates and also very much more than the word implies. It is less than the traditional biography inasmuch as it omits those details of Saeta's life that would usually find a prominent place in such a literary genre. This is even more true of the manuscript as left us by Kino. In presenting chronologically sixteen vignettes of as many Jesuit missionaries who met with violent death at the hands of the natives of northern Mexico, Kino logically reserves the last and most prominent place for Saeta. But he never came around to filling in the blank page other duties and other interests claimed his time and attention.

In the present edition, appearing on the 276th anniversary of Saeta's death and of the composition of the biography, we have endeavored to supply as far as possible the details omitted by the author. This we strive to do both in this Introduction and more briefly in the series of vignettes just alluded to.

But Kino's biography of Saeta, despite its brevity, is also very much more than just another life of another missionary. It is the detailed and fully documented history of one of the most significant religious expansions in the Americas, with the consequent enlargement politically and culturally of the same vast territory. When Kino reached Pimería Alta (present northern Sonora and the State of Arizona), the northernmost rim of Christendom (the chain of established missions as also Spanish military and civil control) ran from Batepito through Chuchuta (just south of the site of the historic presidio of Fronteras to be erected a few years later), Bacoache and [5] Bacanuche, and then southward to Cucurpe on the route to Tuape and Opodepe.

In the years that Kino evangelized and explored Pimería Alta, he added an extensive region to New Spain: westward to the Gulf of California, northwestward to and beyond the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, northward to Casa Grande and even beyond as far as the Río Azul, eastward along the Río San Jose de Terrenate (later called the San Pedro River). As Saeta was assassinated in 1695 and Kino composed the bulk of the biography in the course of the same year, the span of time dealt with is necessarily a brief one - 1687 to 1695, with an exceptional wealth of details for the years 1694 and 1695.

The life of Saeta is Kino's only serious attempt at biography, and after the "Favores Celestiales" his longest composition. It shows greater unity and degree of completion than the latter work. The biography taught Kino a decisive lesson in historical composition, namely the preservation und use of primary sources. A considerable portion of the book is the reproduction of correspondence of Saeta, and of religious and military leaders with Kino. The preservation of such documentation became with Kino a life-long habit; and later, when he came to prepare the "Favores Celestiales" for the press, he had at hand his own archive of precious source material.

In the Saeta biography, turbulent and confused events are disengaged and presented clearly, with sufficient background, evident cause and affect. The few guilty are clearly distinguished from the numerous innocent, an important distinction that had its practical consequences in the treatment meted out by military officials and in the ultimate pacification of the region, as well as in the decision of the highest ecclesiastical authorities to step up rather than abandon the evangelization of the area.

To help the reader follow his narrative more closely, Kino drew two very accurate maps of the entire region which in themselves are important landmarks in the cartography of Mexico: 1) the "Teatro de los Trabajos Apostólicos" (the superb original in colors is preserved in the Jesuit Central Archives in Rome and is reproduced in black and white in Bolton, [7 ] "Rim of Christendom," 272; and, in the original colors, by Burrus, KC, Plate VIII); and 2) the "Muerte del Venerable Padre Francisco Xavier Saeta" (the original, likewise in colors. is preserved in the same Jesuit Archives, and has also been reproduced in black and white in Bolton, "Rim", 290; and, in the original colors, by Burrus, KC, Plate IX. We have chosen from this map the death scene of Saeta for the Frontispiece of the present volume).

The biography deals with the following topics, listed according to the seven extant books:

1) The coming of Saeta to Caborca.

2) The second period of his work in the same mission.

3) His assassination.

4) An important series of original documents reproduced verbatim, on the optimistic outlook for the future of the region despite the violent death of Saeta, and 15 biographical sketches of earlier missionaries who met a like fate at the hands of the natives without necessitating abandoning the missions. The 16th biographical sketch is that of Saeta.

5) The military efforts to pacify the rebellious natives and the effective cooperation of the friendly natives, but also a tragic mistake with disastrous consequences.

6) The present prosperous state of the missions in Pimería Alta; the historical background; Kino's arrival in the area, his work and success. Special emphasis is given to the objections urged by many against continuance of the missions in the area.

7) The last book is unique in the history of Mexico. It is a presentation of the missionary methods employed by Saeta and still more by Kino and a penetrating analysis of the mental and emotional world of the Pima Indians and their reactions to the teachings and demands of Christianity.

A brief word about each of these topics.

In the First Book Kino develops the narrative by an exact historical account of events, specifying dates, places, distances, and actors in the moving drama of which he himself is the most important. We are given an accurate and detailed explanation of the economic status; the number of cattle donated to the mission of Caborca, even what grains and vegetables were planted and thrived there; what buildings were [9] erected; what expeditions had been undertaken. So specific and circumstantial are the data furnished that one can only conclude that Kino kept an exact diary on which he later drew to compose his biography of Saeta.

In the Second Book Kino relies on a series of letters from Saeta to furnish him with a detailed and reliable account of the events in the second period of the missionary's work at Caborca. In this book we are already given some of the missionary methods employed by Saeta that will be developed at length in the last book.

Book Three is more than a mere recital of the assassination of Saeta; it is a penetrating analysis of the causes that brought it about, with practical suggestions for remedying the situation and preventing its repetition in the future. Kino rejects the false accusation that all the Indians are involved. He proves from numerous sources that the main motive was the injustice and cruelty inflicted on the Indians of San Pedro de Tubutama, particularly the treatment meted out by the Opata overseers; the Pimas were unjustly accused of theft - Kino will often return to the theme - with consequent vexations, cruelty, and deaths caused among them by the invading Spanish troops; further, the Indians of San Antonio de Oquitoa joined in the raid on Caborca because they felt deceived and insulted by the numerous false promises made to them and never kept, particularly that missionaries would be sent to them. Saeta's own charges - children (hijos) Kino calls them - were not guilty of his death, nor were they involved in the rebellion, but rather victims of it.

Book Four, despite its unfinished stage of composition, is one of the most carefully worked out of all Kino's writings. He not only cites countless letters from military and religious officials to prove that he is correct in holding that only a few of the Indians participated in the raid on Caborca - and then only after they were induced by the injustice and cruelty committed against them - but he shows that all these officials were optimistic about the future. To give solid historical basis to his contention, Kino dips deep into Mexican history, drawing vignettes of 15 other missionaries who gave their lives [11] for the same cause and yet their missions were not abandonded but were flourishing today. Why, then, he asks, should anyone want to follow a different policy in regard to Saeta and his missions?

Book Five is a clear account of the campaigns to pacify the rebellious natives and to punish the guilty. He devotes a chapter to the cooperation of the friendly Indians. Kino manfully relates the tragic mistakes of some of the Spanish soldiers and their Indian allies resulting in the massacre of innocent natives and consequent raids on other missions. This frankness may account for the fact that the Saeta biography did not find its way into print during Kino's lifetime.

Book Six is a minute account of the state of the missions and of the area in general. He devotes most of this part of the volume to facing squarely the objections raised against the continuance and extension of the missions in the north. Kino realized that the future of the entire region was at stake. Let us remember that he wrote on this topic on the very eve of his departure for Mexico City, where, as he knew, everyone there from the Viceroy and the Provincial of the Jesuits down would urge these objections against him when he came to beg for funds and more manpower.

To come to the objections. It was claimed that Pimería Alta had no native population or at best a few scattered Indians. Kino answers that the region had more than 10,000; and then goes into specific figures for various localities.

But, insisted the opponents, if there are a few wretched natives, the whole region is one interminable desert. To answer this objection, Kino has the written testimony of Spanish officials; he has exact statistics on the amount and kind of produce; and concludes with the triumphant boast: "This Pimería of ours is in the category of the most fertile and productive lands in all of New Spain - Esta Pimería es de las más fértiles y pingues tierras que tiene toda la Nueva España".

Enemies and opponents of the Pimería enterprise had spread the claim that the natives were incurably lazy and could never be taught to work. For those who insisted on certified and notarized documents, Kino has a supply of them; for those who clamored for visible proof of the natives' ability to work, he pointed to what they had already accomplished at Dolores [13] and other mission centers in constructing houses and churches and in planting fields and harvesting the abundant crops.

But, surely, insisted the opponents, the Indians of the province are born thieves, and work is at best only an occasion al necessity with them. This calumny Kino must thoroughly refute; and in order to do so, he uses a three-fold argument: first, despite all the surprise forays of the Spanish military forces into Pima territory, not the least indication of theft was ever found; secondly, the Generals Juan Fernandez de la Fuente and Domingo Teran de los Ríos during the month of June 1695 did uncover stolen property in possession of the Hojomes at Cerro de Chiricahui, but these Indians are the enemies not the allies of the Pimas; thirdly, the Pimas cultivate their fields and live off the produce, whereas the Hojomes, the Janos and the Sumas are nomadic tribes unaccustomed to work, who find it more agreeable to loot and steal horses, mules, and cattle.

The last objection is an economic one: namely, that the missions and the settling of the North were a heavy strain on the royal treasury. This is an objection, answered Kino, that could be used against any region; what are we to do, stop colonizing and evangelizing in order to save a few pesos? I'll cite in full, says Kino, the royal decree that states that the advantages of establishing missions far outweigh the expenses involved. Who would dare doubt the King's word?

Kino now comes to the last [Book 8] and by far most valuable book for the student of the history of Mexico and the American Southwest for it furnishes him with the key to Kino's methods of winning over the natives, of his being able to travel among them even unescorted when he so chose, of securing their cooperation in evangelizing the area far beyond the limits its of his own mission, of securing their confidence, allegiance, loyalty, trust, and devotion to a degree unparalleled in the mission annals of Mexico.

As I think is evident, the biography of Saeta by Kino is more than the life story of one man. It is the detailed and documented history of the entire region with the political, economic, ethnological, military, geographical, and ecclesiastical phases minutely presented and analyzed.

Excerpts from "Kino's Biography of Francisco Javier Saeta"

Eusebio Francisco Kino 1696

"As Venerable Father Francisco Javier Saeta used to say that a missionary among new peoples needed special talents, temperament and vocation. There is no doubt that a keen sense of charity is worth more here than anything else. The missionary must conduct himself toward these poor natives wholly in and through Christ. He must handle new conversions with a genuine knack, being capable of accepting suffering while he works hard and maintains a sense of tolerance.These qualities are more valuable than other human talents, skills, sophistication, eloquence, ingenuity or advanced and subtle science...

In our opinion the very origin of new conversions springs from where there exists a strong and loving concern for the temporal and spiritual welfare of impoverished and destitute people, even though they may be downtrodden, misguided, and persecuted outcasts.

Kino's Biography of Javier Francisco Saeta

Book 8 Chapter 2

"And we must remember, especially for new missionary works, that it was said: "Go among the rejected peoples" (Isaiah 15:2), so that the missionaries will take up the strenuous task of instructing, teaching, and training in spiritual as well as temporal matters.Such work calls for hardiness, patience, and tolerance; if the missionary is to succeed in fashioning any decent, skillful, gentle, and affable children, these virtues are demanded.

But this is neither well nor sufficiently achieved when one sits perched on his chair ordering subordinates or Indian officials to do what we should be doing personally by sitting down time and again with them on earthen floors or on a rock."

Kino's Biography of Javier Francisco Saeta

Book 8 Chapter 1

"Indians in a new mission are great newsmongers. Whatever good or evil they learn is immediately spread far and wide.

Indians who live far away, even in the more remote sectors, inquire about the missionary priest. They want to know what he does, what he says, what he gives, what he wears and carries, what he teaches, how he speaks, etc. Very many Indians who live a great distance from the Fathers know who they are.

They know whatever they do and say, and they form their own opinions and ideas about them. They will say that a certain Father is good, another is liberal, or that this is the style of this one and that one. "I will take my sons to be baptized by him," etc.

I have traveled deep within the Indian territory where I have met Indians who claim that they have already come to know me in places still farther away, although we certainly have never seen one another before."

Kino's Biography of Javier Francisco Saeta

Book 8 Chapter 4

See topics below on this page to read complete chapters from English translation of "Kino's Biography of Javier Francisco Saeta"

"Kino Writes About Reason for Conversions and Preferential Option for the Poor"

Book 8 Chapter 6 - "Motives And Sublime Goals To Make New Evangelical Conquests Among These New Conversions And Missions"

To download, click

Saeta Biography Book 8 Chapter 6 document (text)

"Kino Writes to Protect the O'odham People"

Book 3 Chapter 1

"The Circumstances And Causes Of The Death Of Venerable Father Francisco Javier Saeta And

What Motivated The Deaths Of The Seven Other Christians, Servants Of The Fathers,

The Pillage And Burning Of Their Houses And Even Of The Holy Images" 1696

To download, click

Saeta Biography Book 3 Chapter 1 document (text)

For entire Book 8 of Saeta Biography, click

Saeta Biography Book Eight Entire Book document (text)

Support of Saeta Biography by Jesuit Father General In Rome

Al Padre Juan de Palacios,

Provincial, México. P. C.

EI Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino me dice que iba escribiendo la vida del venerable Padre Francisco Javier Saeta, últimamente martirizadoen la misión de los Pimas, y que añadiría también las de los demás que en esa Provincia han tenido el mismo dichoso fin. Luego, que acabe esa obra, Vuestra Reverencia hará que se revea, y revista y aprobada, dará licencia para que se imprima; porque tales noticias son de mucha gloria de Nuestra Señor, de la Compañía, y de los apostólicos empleos de esa Provincia.

Roma, 28 de julio de 1696.

De vuestra Reverencia, siervo en Cristo,

Tirso González

Editor Note: Ernest Burrus writes Kino's Saeta Biography was never published because Kino's account of the Tubutama Uprising and Kino's defense was a matter highly sensitive matter to the New Spain authorities.

Articles on Kino's Missionary Philosophy and Missiology

Missionary Kino - Spicer document (text)

Edward H. Spicer

Padre Kino's Missionary Teaching - Polzer document (text)

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

Missiology of Kino - O'Neil document (text)

Charles E. O'Neil, S.J.

Kino's Method of Evangelization - Polzer

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

Overview of Missionary Efforts in the Spanish New World

"The Missionary Enterprise: An Overview"

Luke Clossey

The missionary effort in the Spanish New World was one of the greatest religious and humanitarian endeavors for the times. Dr. Luke Clossey discusses the challenges and the historical context in his article "The Missionary Enterprise: An Overview"

To view, click

Missionary Enterprise - Clossey

"Rules and Precepts of The Jesuit Missions of Northwest Spain"

Charles W. Polzer

Rules and Precepts is a valuable research tool for scholars and for those who are interested in the "anthropology" of Jesuit missionaries. Polzer's authoritative commentary and his translation of the rules and precepts decreed by New Spain's Jesuit provinical make this work literally a "manual on the missions." and gives valuable insights into religious and civil life on the far mission frontier in the 1600s and 1700s.

For Google sample preview, click

Rules and Precepts - Polzer

Medicine Man Kino Providing

Physical and Spiritual Care

Detail of Painting by Artist Jose Cirilo Rios Ramo

Missionary Doctor and Pharmacist

Medicine Man

In the relative absence of pre-Columbian epidemics, native cultures in the northwestern Mexico and Paraguay had few elaborated behaviors and beliefs to deal with unprecedented diseases wrought by maladies such as small pox. … The fact that the Jesuits coupled prayer with clinical care of the sick also empowered them …

Dr. Daniel T. Reff

"The Jesuit Mission Frontier: The Reductions of the Río de la Plata and the Missions of Northwestern Mexico 1588-1700" in "Contested Ground: Comparative Frontiers on the Northern and Southern Edges of the Spanish Empire"

To view Dr. Reff's entire chapter article online, click →

The Jesuit Mission Frontier - Reff

"The Jesuit Missionary in the Role of Physician"

Theodore E. Treutlien

Perhaps more important than any of the Jesuit missionary's other non- religious functions was his performance in the role of physician to the Spaniards and Indians who resided in his mission district. Father Pfefferkorn's observations about the care of the sick and about the sicknesses found among Sonorans, reveal him to have been a man who ombined in varying proportions a pseudo-scientific knowledge of illnesses and their cures with an eminently "common sense" practicality.

The plant and mineral kingdoms of Sonora were believed to contain countless healing materials and antidotes for a wide variety of maladies and poisons. There is at least the implication in Pfefferkorn's description or these medicaments that in Sonora God had been particularly beneficent in compensating for the lack of "doctors, surgeons, and apothecaries" with a plentiful supply of health promoting agencies.

'I'he juice of mescal leaves was considered an infallible antiscorbutic: the root of the same plant healed wounds, while spirits distilled from the root were used as a stormach tonic. With mescal spirits Pfefferkorn cured his own stomach which had been unsettled for six months. Spaniards who had the equipment for the distIllation of mescal spirits charged an exorbitant price for the liquid. …..

Theodore E. Treutlien

The Jesuit Missionaries in the Role of Physician

"Mid-America" 22, no. 2 (April 1940) pg. 120–41.

To view and download entire article, click

Jesuit As Physician - Treutlien

"Healing on the Edge: The Construction of Medicine

on the Jesuit Frontier of Northern New Spain"

Rebecca Crocker

This article examines historical, ethnographic, and archival records to portray how medicine and healing were constructed in this frontier region during the Jesuit period (1617-1767), and the influence of Jesuit philosophy and practice on local medicinal practice. Chambers and Gillespie (2000:228) argue that a geographic region can constitute a "scientific locality" when there exists "a local frame of reference in which we may usefully examine the role of knowledge construction and inculcation." I maintain that colonial Sonora during the Jesuit period constitutes its own scientific, and specifically medical, locality due to three primary factors: ( 1 ) the influence and healing perspective of the erudite and scientifically minded Jesuit missionaries, (2) the area's geographical isolation, and (3) the biopharmaceutical composition of the arid northwest. The available historical record reveals that these three factors interacted to necessitate and encourage the continued use of regional healing substances and practices in concert with imported modalities. Due to the dearth of medical informants from the era, much of the information in this article comes from the broader region of Sonora rather than O'odham territories specifically. Nonetheless, the regional experience of fusing medical techniques and theories is applicable to the O'odham, and the second section of this article will employ a modern ethnographic resource (Bahr et al. 1974) to focus the discussion more specifically on what we can glean about the O'odham historical experience. If we take as true Porter's (1985:192) statement that "health is the backbone of social history," the hypothesis forwarded here is not just important in the realm of healing, but also in the field of regional processes of cultural change and continuity.

The Interaction of Culture Contact, Geography, and Biology

The isolation and apparent desolation of Sonora spelled cultural isolation from the colonial core for a long period following initial exploration of the region by Spanish military parties during the 1540s and 1560s. When European penetration of the area was reinitiated, it took place largely under the auspices of Spain's newest religious order, the Society of Jesus. Whereas the church and state served as "dual columns of royal authority" on the frontier (Radding 1997:11), the institution of the Jesuit mission was the primary foreign influence on local cultural order (see also Sheridan 1992; Valdés Aguilar 2009). The Jesuits distinguished themselves from their fellow religious brethren by refusing tithes, declining to wear the habit, applying themselves to learning the languages of their converts, and educating themselves in the sciences. Many Jesuits on the northern frontier became prolific chroniclers of American natural history, including Manuel Aguirre, Juan de Esteyneffer, Juan Nentvig, Joseph Och, Ignaz Pfefferkorn, Andrés Pérez de Ribas, Hernando de Santarén, Luis Xavier Velarde, and Miguel Venegas, several of whom ministered to or traveled through O'odham territory.

In response to widespread interest in botanical cures, the Jesuits developed what Anagnostou (2007) refers to as a "worldwide drug transfer," in which missionaries from China, India, Japan, the Philippines, and Spanish America interchanged knowledge and materia medica. They took inspiration particularly in natural history, not only for its practical applications to knowledge expansion and healing, but because, on a higher scale, they believed that God's love was embodied in nature's bounty (Acosta 1962). Anagnostou (2007:294) maintains that, "according to Jesuit philosophy and spirituality, nature reflected God's omnipotence and divine providence. To describe and explore nature was, therefore, one way of worshipping God." According to Harris (2005), this predilection to see God in nature opened the minds of Jesuits throughout the world to more readily incorporate and accept the healing traditions they encountered. What is more, as the most educated of the European religious orders, many Jesuits took seriously the mandate to learn indigenous languages as a means to decipher how the order in language reflects the order in customs and culture, a process that then forced them to "contemplate alternative truths" (Reff 1999:36).

Jesuit interest in healing knowledge was compounded by a firmly held belief that "the bodies of their spiritual charges should be aided along with their souls" (Kay 1996:25). The Jesuits held an "activist" approach to missionization, in which the role of healing or witnessing illness was deemed more important than a night spent in isolated prayer (Reff 1999). Jesuit preoccupation with illness and remedy was evidenced in the essays on missionary life they left behind, which addressed sickness, doctoring, and specifically their own roles as physicians. Ignaz Pfefferkorn (1949:178), for example, in his Sonora: A Description of the Province, wrote of his missionary years that "the vigilant care of the sick was one of the most important concerns of the missionary." Missionary chroniclers report having traveled long distances in harsh and uncertain conditions to attend to the sick and baptize the terminally ill lest they be left to take their last breath as "sinners." The report of Captain Juan Mateo Manje (1701), who accompanied Father Eusebio Francisco Kino on many missions of discovery through O'odham territory, noted such activities, stating that "the father rector was confessing the sick and catechizing others in order to baptize them, for they are currently [suffering] from the epidemic commonly called "pitiflor". A sick man died the following night without baptism, [causing] the father great sorrow because he had not counseled him. ...."

Rebecca Crocker

Healing on the Edge

The Construction of Medicine on the Jesuit Frontier of Northern New Spain

Journal of the Southwest

July 1, 2014

To read entire article online, click →

http://www.readperiodicals.com/201407/3449174271.html#ixzz3qGsPGWDP

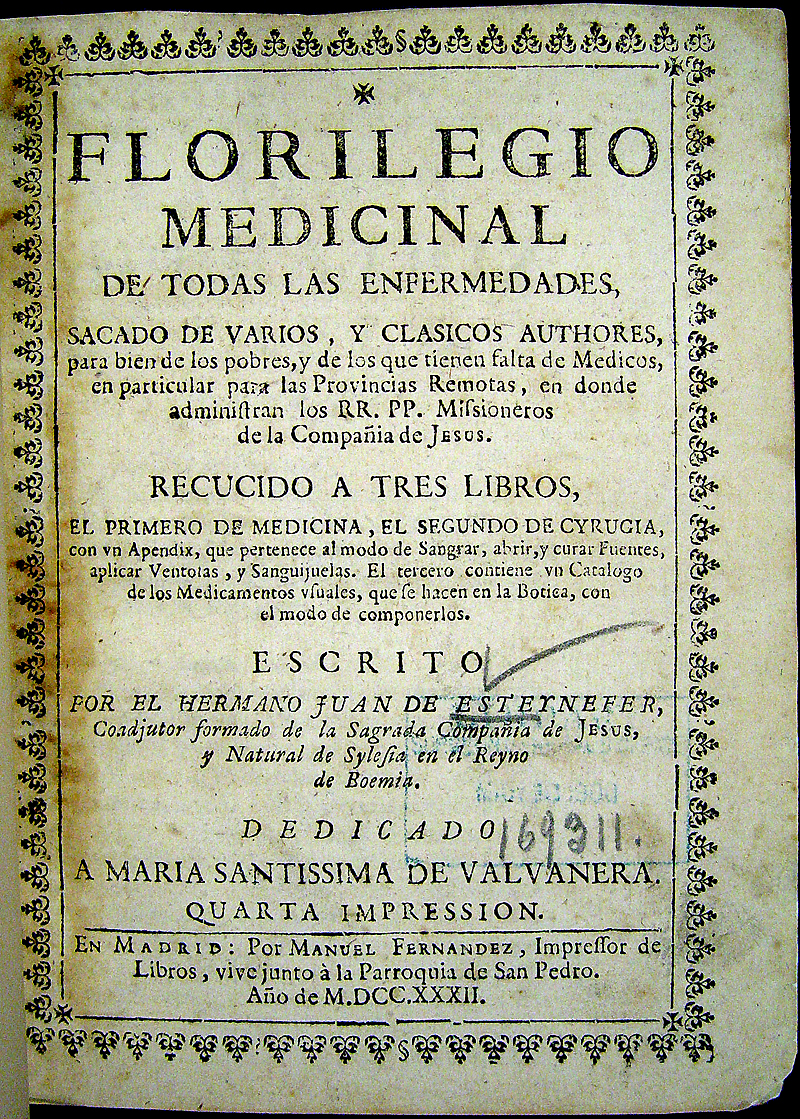

Forilegio Medicinal

By Kino Co-worker Brother Esteyneffer

Medical Guide for Missionaries And 300 Years of Folk Medicine

"Florilegio Medicinal"

Three Books: Medicine, Surgery and Drugs

One of the most important daily non-religious work of the missionary was the missionary's role as a medical doctor. So great was Jesuit involvement in "care of the sick" in the missions that the Jesuits sought and received a papal exemption from the ban on clerics serving in medical roles. Jesuits who assisted the sick and dying were called "Father Operarios." Dr. Treutline identifies Jesuit Brother Juan de Esteyneffer, the author of the Florilegio Medicinal, by his European name - Johann Steinefer. Brother Juan's last name also is recorded as Steinhoffer..

The Florilegio Medicinal is one of the most influential medical guides in Latin America. Jesuit Brother Juan de Esteyneffer was a co-worker of Kino's in Sonora. Brother Juan joined Kino on the trail and helped with the preparations for the arrival at Tubutama of the new missionary Padre Minutuli in 1704. For many years afterwards, Brother Juan traveled to other Sonoran missions teaching the indigenous people herbal medicine.

Florilegio Medicinal was an instructional medical guide combining European medical knowledge with knowledge of Native herbs and other medicinals of Mexico. Written in an understandable and accessible language, it is composed of three sections: Medicine, Surgery, and Drugs.

Florilegio Medicinal was first published in 1712, the year following Kino's death. It's popularity resulted in its reprinting four times during the 18th century and again in the 19th and 20th century. It was still being used as late as the 1970's by some folk healers in the American Southwest and Northern Mexico. To view the guide, click Forilegio Medicinal.

Brother Esteyneffer was born in Europe. He was assigned to the Pimería Alta and ministered at Tubutama in 1703. He also served in other missions in today's Sonoran towns of Vecora, Matape, Tecoripa, Arizpe and Sinoquipe. He died in Tecóra in 1716.

The Jesuit contribution of new medicines and drugs to the world's pharmacy are legendary. The most famous was "Jesuit's Bark" (cinchona bark or quinine) which was the first effective drug to treat malaria. The Jesuit missionaries in Peru were taught the healing power of the bark by Native people between 1620 and 1630. The Jesuits then synthesized the bark and distributed the medicine throughout the world. Jesuit bark was used as the primary treatment for malaria up to the 1940s. For more information, click Jesuit Bark.

More about Esteynefer's "Florilegio Medicinal" at the U.S. National Library of Medicine website sponsored by the U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH). Click and scroll to bottom of the page at →

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/exvotos/guides.html

Jesuit Father General Sends Esteyneffer to Help Kino

"La facilidad que se ofrece, y veo en las cartas de los padres Kino y Salvatierra, del tránsito a las Califomias me obliga a instar de nuevo el que se procure la entrada de todas veras y calor ...

Considero que a los que hubieren de entrar les será de grande alivio el llevar consigo al hermano. Y sé que el hermano Juan Steinefer [Esteyneffer], irá con gusto. Vuestra Reverencia le envíe luego a los pimas para que allí le ayude al padre Francisco Kino. Y esto Vuestra Reverencia lo ejecute, ahora se disponga la entrada alas Califomias, ahora no. Pues estoy seguro que es un muy buen operario catequizando e instruyendo.

Roma

21 de mayo de 1695

De Vuestra Reverencia siervo en Cristo

Tirso González."

Editor Note: Letter from Jesuit Father General Tirso González, Rome, to Provincial of New Spain Diego de Almonacir, México City dated May 21, 1695.

Kino Receives A Mother's Thanks on the Colorado River

"Favores Celestiales" 1702

Eusebio Franicsco Kino

"And in this journey inland, as in my preceding one of the past month of November, they received the word of God with so much appreciation that they gave me many infants to baptize. Of the two little ones whom I had baptized in the preceding journey inland, this time the mother of one, called Thyrso Gonzales, brought him to me, for, having recovered, he was fat and healthy. Many other mothers also brought me their children, asking me to baptize them …."

Eusebio Franicsco Kino

March 2, 1702

Kino's Historical Memoirs

Volume I, page 349

Editor Note: Kino's many diary entries describe his taking detours from his planned routes to baptize and care for the sick and dying. A mother expressed her gratitude to Kino for healing her infant son on his fourth and final trip to the Colorado, On this trip four thousand Native people from the various Colorado River tribes came to see Kino near today's San Luis - many swimming across the Colorado River at its high spring flow. The next day Kino would travel to the Colorado River Delta and prove his hypotheisis that California was not an island as commonly then believed. His proof of an overland route to the recently revived California missions could have made Kino's supply of them easier.

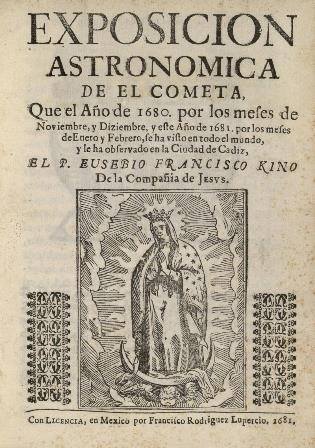

Kino's Drawing of Our Lady of Guadalupe

From His Sky Map of the Comet's Path

Exposición Astronómica del Cometa

The Missionary Guadalupano

"Padre Kino’s Devotion to the Virgen de Guadalupe"

Raul E Ramirez

Kino’s relationship to the Virgen de Guadalupe began prior to this arrival to Mexico City. While waiting in Spain to embark to the New World, he wrote to the Duchess of Aviero and Arcos, Maria de Guadalupe de Lencastre. The Duchess was named for her patron saint, the Virgen de Guadalupe, the Spanish Dark Madonna (enshrined in Estremadura) and was known for her generosity to missionaries, especially those assigned to missions in the Marianas, Philippines, and China. Kino wrote to the Duchess expressing his interest in serving in the Orient, but noted that as he was assigned to the New World, he was bound by his vow of obedience to his Jesuit superiors.

Padre Kino arrived in Mexico City on June 1, 1681. While he waited for his first assignment in New Spain, he was encouraged by fellow priests and colleagues to write about a comet that he had studied in Europe in 1680 and still visible in Mexico City in 1681. This comet was called the Great Comet of 1680 and also Heaven’s Chariot. Kino published a short thesis on the comet titled "Exposición Astronómica de el Cometa."

On the booklet’s cover, Kino used the image of the Virgen de Guadalupe de Tepeyac, and in the introduction he describes her image. Regarding the miraculous image of the Virgen on Juan Diego’s tilma, he stated, “We have so close (to us) a copy of that divine lady, Mother of God, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, who bestows protection on Mexico. She is surrounded by the sun, embellished by the stars, with the moon as her carpet and uplifted by a Cherub. There is nothing in the heavens, commanding as the moon may be, that does not serve as adornment to her image. What would the original be (to behold)?” Padre Kino sent several copies of his thesis to the Duchess in Spain so that she could distribute to acquaintances with an interest in the topic.

In his letters to the Duchess from Mexico City he shared his views on the comet and noted that he celebrated Mass weekly at the Capilla of the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe at Tepeyac. On July 4, 1681, he wrote to the Duchess that he still hoped to go to China if it was God’s will and that he celebrated mass every week at the sacred shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He also prayed for his intention and for the Duchess’ family including her three children, Joaquin, Gabriel and Isabel. Kino stated that he was sending images of Our Lady of Guadalupe for her family which he “placed against the sacred picture itself of Our Lady of Guadalupe….. I kept all five images on the altar, on the very corporal where the sacrifice of the Mass under the species of bread and wine takes place--- the price of our redemption” (Burrus, p.111).

Later, on June 3, 1682, enroute to his first assignment to establish missions in Baja California, Kino wrote to the Duchess averring that “The City which by God’s favor and that of the Blessed Virgin we shall found in California within the next three to five months, will be called, by God’s grace, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de las California.” (Burrus, p.122).

In communications with Padre Francisco de Castro, a fellow Jesuit, Kino related that they arrived in La Paz in Baja California and went ashore on April 2, 1683. Kino reported that he and Padre Matias Goñi, engage the native people, expressing their peaceful intentions and showing them religious images. “We showed them a crucifix and on another day and image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, but they gave no sign of actually having or ever having had any acquaintance with these objects or with matters concerning the Catholic religion” (Burrus, p.130). At that time, Kino was trying to determine if previous expeditions had contact with the native people in the area. Kino states that on Palm Sunday palms were distributed and work continued on the small church and fort which was called the Real de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. They shared food with the natives and taught them to make the sign of the cross. Kino commented that “Within a few months we can begin to administer baptism, since these Indians seem to me to be the most tractable, affable, cheerful and jovial in all America” (Burrus, p.131). Unfortunately , on July 3, 1683 the peace was broken by soldiers in the Spanish Garrison who fearing a plot against them, fired a cannon on sixteen unarmed Guaycuros warriors, killing ten of them; a week later, Kino was forces to abandon his first mission in Baja California as the Spanish soldiers withdraw.

Kino wrote to the Duchess on December 15, 1683 and reported as of October a new mission was started at San Bruno, Baja California. He shared that a lovely picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe was placed on the main altar. Ten months later he wrote to the Duchess once again, thanking her for the incense figures that she sent, adding that they were used them on the altar of Guadalupe for his solemn final religious profession as a Jesuit on August 15, 1684.

Yet by May of 1685, this venture also failed when the site was abandoned due shortage of water and provisions. Nevertheless, it may be said that Kino’s foray into this region was successful in part, as he was the first European to cross the peninsula from one side to the other. At that time, Baja California was thought to be an island but after Kino was establishing his missions in the Pimería Alta, he was able to show that Baja California was in fact a peninsula and not an island.

Kino’s letters to the Duchess stopped with his arrival into the Primería Alta, and while he did not name any of his new missions after the Virgen de Guadalupe, his Marian devotion continued. Other missions were named after Our Lady including Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (1687); Nuestra Señora de los Remedios (1687); Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera (1689); Santa Maria Suamca (1693); La Purisima Concepción de Nuestra Señora de Caborca (1693); Nuestra Señora de Loreto y San Marcelo de Sonayta (1693), and Nuestra Señora de la Ascension de Opodepe (1704).

Raul E Ramirez

"Padre Kino’s Devotion to the Virgen de Guadalupe" 2010

Bibligraphy

Bolton, Herbert Eugene. "The Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer" New York: Macmillan 1936

Burrus, Ernest J., S.J. "Kino Writes to the Duchess: Letters of Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J., to the Duchess of Aveiro; an Annotated English Translation, and the Text of the Non-Spanish Documents" Rome and St. Louis: Jesuit Historical Institute 1965

Kino, Eusebio Francisco, S.J., "Exposición Astronómica de el Cometa, 1681… " Mexico City 1681

Kino Dedicates His Life To Our Lady of Guadalupe

In His Comet Treatise

"Exposición Astronómica del Cometa" 1681

Eusebio Franciso Kino, S.J.

Señora de ambos Orbes María, Madre de Dios del Titulo Advocación, y Renombre del Mexicano Guadalupe, a quien consagro mis suceíos, y sucesos, y pongo la contingencia que puedo correr con los demas mortales, para que con su poderosissimo Patrocinio seguro de las comunes azechanzas de este mundo, llegue a conseguir la celeste patria donde se lleva quando a y de delicia, menos la mudanca, y alternada sucesion de las cosas, Omnia ad majorem Dei, Dei pareque honorem amorem, et gloriam.

Eusebio Franciso Kino, S.J.

"Exposición Astronómica del Cometa" 1681

Mexico City

Editor Note: Written in 1681 - These are the last words of Kino's astronomical treatise written immediately before he leaves to begin his 30 years of mission work on and beyond the Spanish frontier. Kino names his first two missions of his 26 missions and visting stations. In Baja California he honored of Our Lady of Guadalupe by naming in Her honor his missions at La Paz and San Bruno (north of Loretto). Kino writes that he made his final vows to become a fully professed Jesuit priiest on August 10, 1683, in front of a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe at the altar of Mission Our Lady of Guadalupe at San Bruno.

Duchess de Abeiro y Arcos and Family

Kino Writes The Duchess About His Devotion

Letter to María Guadalupe de Lancaster 1681

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Your Excellency

The Peace of Christ Jesus and the Love of Our Lord be with you!

A month ago, within the first days of my arrival in Mexico City, I wrote to your excellency, giving you an account of our entire trip and voyage to the missions. Quite likely, that letter will reach you at the same time as this one. I entrusted all my letters to Reverend Father Baltasar de Mansilla, Procurator of the Philippines and Marianas, to put them in a mail pouch sent from Mexico to the Spanish court in Madrid.

Reverend Father Baltasar de Mansilla is favorably interested in the eastern missions, especially the Marianas. When in the preceding month of March he sent those missionaries who had arrived here in the fleet ten months previously, he wrote to the Reverend Father Superior of the Mariana Islands to keep for that mission as many as he wished. He will write to the same effect regarding the other missionaries (who two months ago came here with me on the dispatch boat), when he sends them, God willing, to the Orient. As is evident, he makes every effort to help the Marianas.

Reverend Father Baltasar is also trying to get me to China. Accordingly, a few days ago, he spoke about the matter to Reverend Father Provincial of the Mexican Province in the endeavor to secure me for his own eastern missions. Reverend Father Provincial, who is planning on sending me to California in the company of a veteran missionary, when within a few months (if God so wishes) ships, soldiers and a goodly contingent set out to explore more carefully than heretofore that extensive island or peninsula, has not yet given his final decision to Reverend Father Baltasar. He will probably do so when Father Antonio Cereso comes here from Puebla in some two or three weeks.

Although he is the one designated for the Philippines, he will quite likely remain in the Mexican Province because of the great difficulties which he experienced during the voyage; and so, perhaps, I can manage to be sent to the Orient in his place.

In the meanwhile, I dare not prefer, ask for or desire one mission rather than another, lest I be reminded: "You know not what you are asking for." But until then, I am earnestly commending every day this intention to Our Lady of Guadalupe, so that superiors decide what is most pleasing to the all good Lord. And when for this purpose I go every week to say Mass at the sacred shrine of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, Our Lady of Guadalupe, I am careful to commend, as well as I can, the intentions of your Excellency, of your husband and of your three dear children, Joaquin, Gabriel and Isabel.

I am writing this letter on her feast; and, hence, I am sending her an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe and a pious chain; I would have the latter be a symbol of her close attachment to Our Lord. The other four images I should like to give to the other four members of your devoted family, namely, your Excellency, his Excellency, and Joaquin and Gabriel, so dear to me in Our Lord. All five images were placed against the sacred picture itself of Our Lady of Guadalupe. I acquired them when I went out of the city to say Mass in the shrine of the Blessed Virgin Mary. While I said Mass on the altar of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, I kept all five images on the altar, on the very corporal where the sacrifice of the Mass under the species of bread and wine takes place - the price of our redemption.

For several days now I have not seen the "Virreina" [the friend of the Duchess, wife of the Viceroy of Mexico] but soon I shall be seeing her, God willing. Just a few days ago, when we celebrated in our church the feast of Saints Peter and Paul apostles, his Excellency, the Viceroy, deigned to add to the solemnity by his presence.

On June 23rd, at six o'clock in the evening, we experienced a severe earthquake. Many public processions with prayers have taken place to secure rain. I suspect that the exceptional drought is one of the results of the comet; torrential rains occasionally follow a drought. May the divine clemency in its compassion protect us and ever keep us from harm!

We are awaiting the return soon of Reverend Father José Vidal from Puebla, where he conducted a mission. To his exquisite kindness and goodness I am deeply indebted, as also to Reverend Father Baltasar de Mansilla.

If your Excellency has sent to Cadiz the Caravacan crosses which I humbly requested while I was still in that city, our devoted Brother Marcos de Sotomayor will reimburse you. He went to Madrid as the companion of the two Reverend Fathers Procurator now on their way to Rome. I earnestly commend all of them to your Excellency and myself to them, wishing them a safe trip.

Unless the fleet leaves from Vera Cruz earlier than scheduled I shall attempt to soon let your Excellency know in another letter to what mission my superiors are assigning me. Whether they are sending me to the Orient or whether they are keeping me for the missions here in New Spain or California, I shall always remain most deferentially devoted to your Excellency, ever mindful of you in my prayers and sacrifice of the Mass. The very presence of the sacred image of the Blessed Virgin Mary signed by you, which you so kindly sent to me in Cadiz from Madrid and which I now carry in my breviary, will readily remind me to give you a daily intention.

To the fervent prayers of your Excellency, of your dear children and of your entire devoted family, I earnestly commend myself and the missions of the oriental and western worlds, especially those of limitless China.

Mexico City, July 4, 1681

Most devotedly yours in Christ,

Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J.

Kino addresses the letter envelop:

"A la Exc.ma Señora Duquesa de Abeiro y Arcos, que Dios guarde muchos años en Madrid. M.R."

Editor Note: The Duchess of Aveiro y Arcos, María Guadalupe de Lancaster, (1630 - 1715) was from a noble and wealthy Portuguese family. She was a great patron of charities and of the missions in all parts of the world especially Jesuit foreign mission. She was called "The Mother of The Missions." She was an accomplished linguist, patroness of letters and famous painter who my have been a pupil of Velasquez. She was a person of great influence in the courts in Madrid, Lisbon and Rome.

The Duchess and Kino began their correspondence during Kino's 2 year stay in Spain while waiting to take ship to the New World. Their correspondence continued while Kino worked in New Spain. The Duchess and Kino never met in person. Kino's letters to the Duchess totaling over 30 give great insight into Kino's hopes and ideas. Most of Kino's original letters that are known to exist are owned by the Huntington Library.

Letter Summary by Ernest Burrus: Kino writes to the Duchess from Mexico City, July 4, 1681. Father Mansilla dispatched all of Kino's letters by diplomatic pouch. Unless the fleet sails sooner than planned, Kino will Let the Duchess know to what mission he has been assigned - the Orient, Mexico or California. Favorable attitude of Father Mansilla and Vidal towards the missions. Mansilla is trying to effect Kino's passage to China, but the California expedition may need him. The one hope is for Kerschpamer to remain in Mexico and for Kino to take his place in the Orient. At the shrine of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Earthquake in Mexico.

The Missionary Guadalupano

Composite Drawings by Artist Ettore ("Ted") DeGrazia

"Eusebio Kino: Misionero Infatigable, Ferviente Guadalupano"

Enciclopedia Guadalupana

Xavier Escalada

Kino, Eusebio Francisco

(1645-1711)

El insigne misionero y sabio jesuita nació en Segno, Tirol y murió en Magdalena, Sonora. Fue el primer apóstol de las Californias, Sonora y Arizona; al llegar a México en junio de 1681, desconocía el lugar a donde sus superiores le enviarian a misionar. En carta del 4 de julio dirigida a la duquesa de Aveito y Arcos, entusiasta protectora de las misiones de los padres jesuitas, le dice: " ... cada día procuro encomendarme con toda devoción a la bienaventurada Virgen de Guadalupe, para que mis superiores hagan lo que más agrade a Dios, y a este fin voy cada semana a celebrar misa en el sagrado templo extramuros, dedicado a la tres veces admirable Madre de Dios, la Virgen María de Guadalupe".

A dicha duquesa y a sus hijos envió estampas guadalupanas, tocadas al sagrado lienzo. En carta del 3 de junio de 1682, le comunica a la misma duquesa la grata noticia de que su destino será las Californias, aceptando la voluntad divina, ya que mucho había deseado ir a China. Le dice que en unos meses fundarán, en lo que él llama la mayor isla, la ciudad de Ntra. Sra. de Guadalupe de las Californias. El 20 de abril de 1683, en la relación enviada al P. Ximénez, asienta que "a 31 de marzo, entramos en la gran Bahía de Ntra. Sra. de la Paz, que tiene su entrada en 24 grados 55 minutos de altura ... el lunes, empezamos a fabricar una pequeña iglesia y fuertecito, o Real de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe ... "

En carta del 27 de julio de 1683, dirigida al mismo padre le dice, refiriéndose a los indios: "Nos vienen aver muy a menudo a este Real de Guadalupe, trayéndonos regalos ... y una vez también unas perlitas que ellos no las estiman mucho, no hacen mucho caso de ellas, no se aplican a pescarlas, aunque verdaderamente las hay y muchas de buen oriente en toda la bahía, y se han sacado muchas de ellas que son más de doscientas las que han dado de limosna a la Virgen Santísima ... " En todas estas cartas irradia el apóstol guadalupano de las Californias, su amor a la Virgen del Tepeyac, devoción que supo sembrar en aquellos dóciles y buenos indios del Real de Guadalupe.

Gran matemático y cosmógrafo, de indomable espíritu explorador, organizó las misiones de la Pimería Alta (Sonora y Arizona), trazando los primeros mapas, y recorriéndola incansablemente en cuarenta expediciones. Escribió vocabularios de las lenguas indígenas y muchas monografías sobre sus viajes y experiencias misioneras.

Vino a México por amor a la Guadalupana y se entregó a la evangelizacion con tal talento y vigor que el gobierno |492| de Estados Unidos le ha exaltado como fundador de las misiones y poblaciones en los desiertos de Arizona. Su estatua se encuentra en el Statuary Home de Washington, entre los fundadores de América.

El presidente Alvaro Obregón hizo publicar el diario de sus increíbles correrías y descubrimientos. Entre tantas iglesias o misiones que fundó destaca la de San Xavier del Bac, donde aún se conserva la imagen de la Guadalupana que él mismo allí colocara; y en la obra "Delineación y Dibujo de las Partes del Cielo" trazó de su propia mana una copia de la Virgen para la portada.

Xavier Escalada

"Kino, Eusebio Francisco "

Enciclopedia Guadalupana: Temática, Histórica, Onomástica 1995

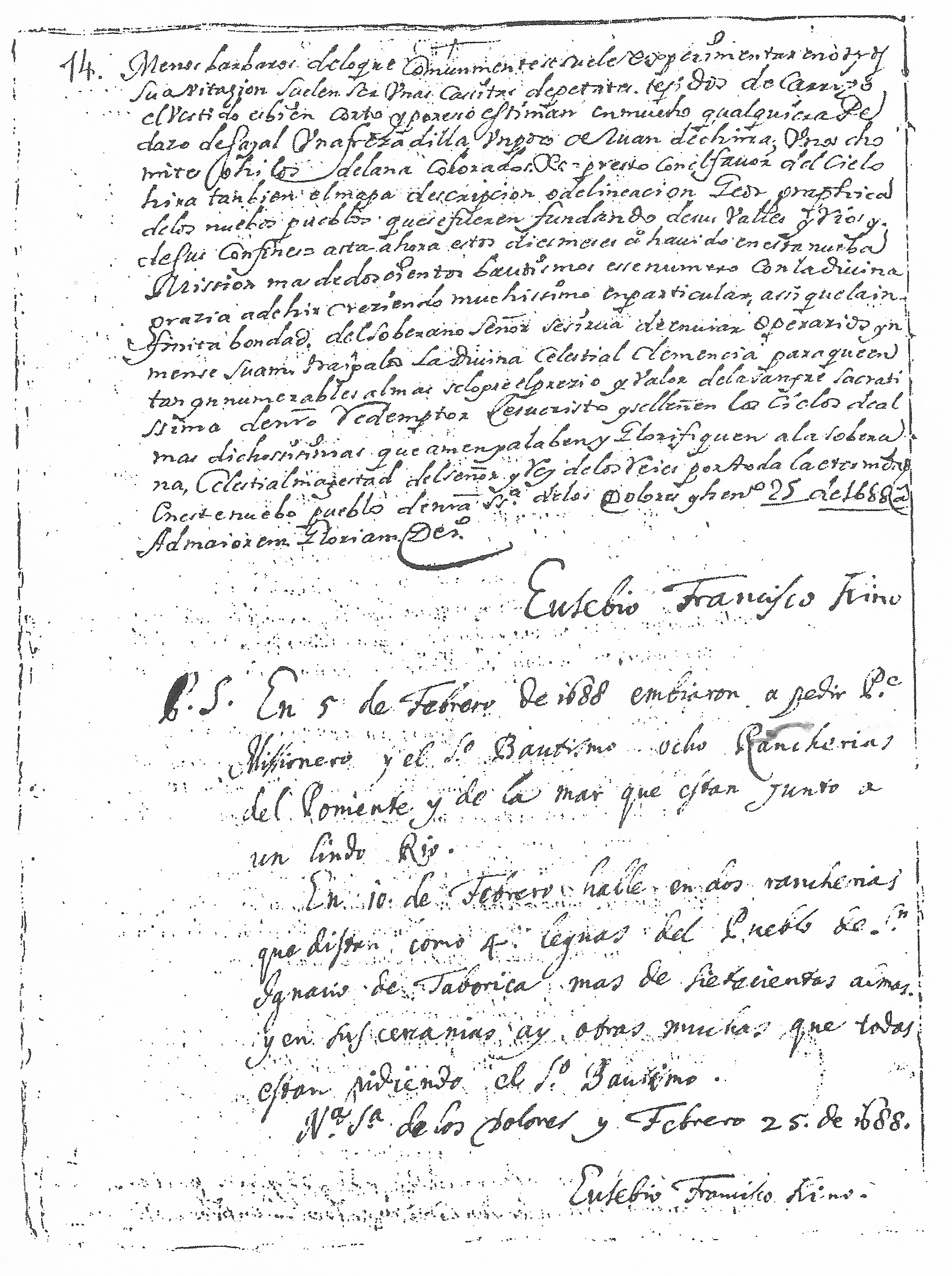

Last Page of Kino's "Breve Relación" with His Signatures

Writings about Kino's Work

Kino Reports About HIs Assignment to and

First Year Among The O'odham People

"Breve Relación De La Primera Entrada

a la Gentilidad de los Indios Pima 1688"

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Breve relación de la entrada que desde 13 de marzo de 1687 se hizo a la nación y gentilidad de los indios Gentiles Pimas y buenos principios de su conversión a nuestra Santa Fe Católica. Escrita por el Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino de la Compañía de Jesús, que de sus superiores fue enviado por misionero a dicha conversión.

Desde que, en veinte de noviembre de 1686 años, por orden del Padre Bernabé de Soto, salí de México para venir a la conversión de estos indios gentiles pimas en esta América Septentrional, en 16 de diciembre, al pasar por la ciudad de Guadalajara, alcancé de la Real Audiencia un mandamiento que con la nueva Real Cédula que tiene inserta, tanto favorece a las nuevas conversiones cuanto quizás hasta ahora no se habrá oído. La fecha de la nueva real cédula es en la finca del Buen Retiro de Madrid, el 14 de mayo del mismo año de 1686, y contiene entre otras acostumbradas, las siguientes muy católicas palabras:

"Por cumplir con tan precisa obligación de evangelizar a los indios y aplicar todos los medios, esfuerzos y recursos que fueren posibles para que se fomente causa que es tan del servicio de Dios Nuestro Señor - quien con su gran providencia retribuye siempre generosísimamente a mi real monarquía - y deseando cumplir con esta obligación, que la considero por la más principal y de mi mayor deseo, he acordado dar la presente, por la cual ordeno y mando a mi virrey de la Nueva España y a los presidentes y oidores de mis audiencias reales de México, Guadalajara, Guatemala ya los gobernadores de la Nueva Vizcaya y Yucatán, que luego que reciban <134> esta mi Cédula pongan especialísimo cuidado en que se vayan congregando en pueblos y convirtiendo a nuestra Santa Fe Católica todas las naciones de indios gentiles que hubiere en el distrito y jurisdicción, que comprende la gobernación de cada audiencia y gobierno" .

Hasta aquí la catoliquisima Real Cédula que tambíen, para facilitar más dichas conversiones, concede veinte años de privilegio a los indios que de aquí adelante se fueren convirtiendo a nuestra Santa Fe Católica, para que de ninguna manera puedan ser obligados a los trabajos de minas o haciendas, ni aunque se presenten órdenes con mi sello real.

Con este Real mandamiento de la Audiencia de Guadalajara y la Real Cédula, llegué a las misíones de Sinaloa a principios de febrero de 1687, y pocos días después, al nuevo real de las nuevas riquísimas minas que llaman de Los Frailes, que bien se reconoce que son el premio que Nuestro Señor ( según dice la dicha Real Cédula) siempre retribuye a la Católica monarquía. Ya principios de marzo, llegué a las misíones de Sonora.

Y pasando a Oposura y Cumpas a verme con el nuevo Padre visitador Manuel Gonzáles. Le hallé tan bien dispuesto a atender esta nueva conversión de estos Pimas, que quiso en medio de sus muchas ocupaciones, venir a ella en persona el camino de más de 50 leguas. Al pasar por el real de minas de San Juan dio el obedecimiento al Real mandamiento de la Audiencia y a la Real Cédula el alcalde mayor Don Antonio Barba de Figueroa. <135>

En 8 de marzo pasamos por Guépaca, misión del valle de Sonora, que está a cargo del Padre rector Juan Muños de Burgos, el cual tambíen estaba dispuesto para entrar en persona a esta nueva conversión.

Dos días después, el Padre visitador y yo llegamos a Cucurpe donde el Padre José de Aguilar nos recibió con muchos arcos y con muchas cruces y con linda música. Enviamos a avisar a los indios Pimas (pues sus primeras rancherías ya no distan de Cucurpe sino 5 leguas) que de ahí a dos días, iríamos a verlos; pero recibimos la desconsoladora noticia que su gobernador no estaba allí; pues pocos días antes se había ido a tierra muy adentro. No obstante, por cuanto tambíen nos pedía mucho un topil de una de estas rancherías, gravemente enfermo, que antes que se muriera por sus largos ya peligrosos achaques, le fuéramos a bautizar, en 13 de marzo, entramos a estas rancherías el Padre visitador, el Padre José de Aguilar y yo, con el gobernador y alcalde de Cucurpe. Al llegar a la ranchería donde estaba el topil enfermo, después de catequizado, le bautizó solemnemente el Padre visitador: llamose Ignacio y le casó por la iglesia. Quedó dicho topil con este bautismo consoladísimo y de allí a dos días, después de 6 meses de enfermedad, se fue muy gozoso, como esperamos, a gozar de la dichosa eterna bienaventuranza.

Y entrando a la principal ranchería llamada el Bamotze (que después se llamó y se llama nuestra Señora de los Dolores), fuimos recibidos con grandísima alegría de todos los naturales, con cruces y arcos puestos; y nos tenían prevenida una buena ramada en que pudiéramos <136> decentemente decir misa, además de una de sus mejores casitas en que pudiéramos dormir. Desde luego dijeron estaban muy deseosos de bautizarse y ser cristianos y habían enviado a llamar a su gobernador y se esperaba su venida cuanto antes.

El Padre visitador con sus muchas ocupaciones determinó volverse el día siguiente a su santa misión de Oposura donde los jesuitas tenían un colegio y dejándonos en la pacífica posesíon de este pueblo, dejó tambíen el que a nuestra elección entrásemos o no entrásemos en la tierra más adentro, a ver si había gente y sitio o rancherías a propósito y sin demasiada distancia de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores.

Luego, al punto que el Padre visitador se fue para Oposura y Cumpas, el Padre José de Aguilar y yo - con el gobernador y alcalde de Cucurpe y con otros cinco o seis pajes o criados del Padre y con dos guías de este pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores - habíendonos informado de las rancherías de los alrededores, nos pusimos a caballo. Y caminando hacia el Noroeste como siete u ocho leguas en un muy lindo y grande valle, hallamos una ranchería llamada Caborica, que por orden que teníamos del Padre visitador de que el siguiente pueblo de esta misión se llamase San Ignacio, la llamamos y hasta hoy se llama San Ignacio de Caborica. Sus naturales nos recibieron con mucha alegría y contento y - siendo así que solo dos o tres horas antes que llegáramos a su ranchería, habíamos enviado a avisar de nuestra venida - nos recibieron con una muy linda cruz puesta en el medio de su ranchería con un lindo arco <137> ornado, como tambíen la cruz estaba ornada de muy lindas rosas y flores, y nos desocuparon la mejor casa de la ranchería, que era de barro y terrado, para nuestra habitacíon. Tambíen su gobernador que estaba tierra adentro ya le habían ido a avisar y vino a media noche, en medio del común consuelo de todos. Hubo una india que estuvo llorando muy mucho y con mucho desconsuelo; le pregunté por medio del interprete de la causa de su triste llanto, y respondío estaba tan sumamente triste y desconsolada porque los Padres no habían venido a esta ranchería tres o cuatro meses antes; que en este tiempo se le habían muerto dos hermanas sin bautismo y sin el remedio de su eterna salvacíon. Todos dijeron que estaban muy deseosos de recibir el santo bautismo.En esta ranchería o pueblo de San Ignacio, hay un lindo río, más grande que el de Cucurpe y Sonora, con mucho pescado, con muchas y muy lindas tierras de riego, con muy grandes, muy vistosos y frescos álamos; sale este río de los Hímeres, y del Noreste corre al Sureste hacia el brazo de mar de la California, que está a la distancia de 40 o 50 leguas.

El día siguiente 15 de marzo, dijimos misa en San Ignacio y como nuestros mozos nos dijeron que para volver a nuestro primer pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, había tambíen otro camino aún más llano y más ameno, aunque algo más largo que el por donde habíamos venido, determinamos ir por él, y a las cuatro o 5 leguas de amenísimo camino, hallamos la ranchería de los Hímeres; y su topil el principal, nos recibío con grandísimo contento con una cruz puesta; y por estos caminos a veces desde lejos nos daban voces, diciendo <138> con grande alegría: íPare, ni mama!, que quiere decir íOh Padre, mi querido Padre! Aquí le pusimos San José que es hoy el pueblo de San José de los Hímeres, el tercero de esta nueva misíon.