Kino Pilgrimages - The Camino de Kino

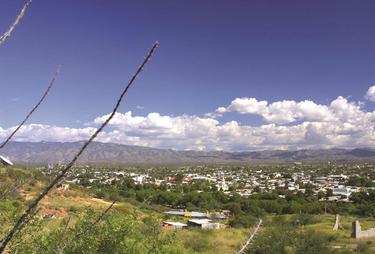

Magdalena de Kino

Misison San Xavier del Bac

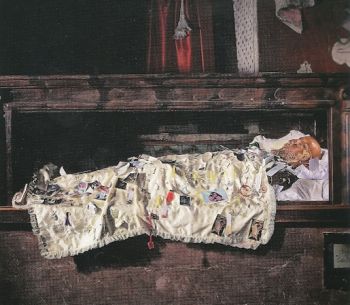

Pilgrims at Reclining Statue of St. Francis Xavier

Magdalena de Kino, Sonora

Magdalena Pilgrimage

Living Tribute to Kino

Although Padre Kino died more than two centuries ago, he never has been forgotten by the descendants of the Indians whom he served. To this day they pay homage. They journey on foot, by horseback, and in wagons from Arizona's Papago and Pima Indian Reservations, and from Sonora's far-flung communities to Magdalena each October to pay him homage. Volumes have been written in praise of the great missionary, historian, ranchman, explorer and mission builder, but no tribute is so eloquent as that annual trek of the Indians whose ancestors first heard The Word of the white man's God and His Disciples from Kino's lips and who had their first contact with the Old World's civilization through him.

Bernice Cosulich

"Tucson" 1953

Pilgrimage To Magdalena and The Festival de San Francisco

James S. ("Big Jim") Griffith

The religious fiesta held every October 4 in Magdalena de Kino is by far the most important pilgrimage event in the Sonoran Desert. It attracts thousands of people to the old mission town. Many walk sixty or a hundred miles as an act of devotion to the saint.

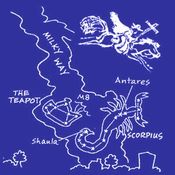

In order to understand it, we must know a little history. Father Kino, who did so much to open this region to European evangelism and settlement died in 1711 and was buried in Magdalena, some sixty miles south of the present international border. His patron saint, and the patron of missionaries in general, was Saint Francis Xavier, a remarkable sixteenth-century Jesuit who did intensive missionary work in both Japan and India, died off the coast of China in 1552, and found his last resting place in the then Portuguese colony of Goa on the east coast of India. His body was preserved in lime for his final journey. That it arrived and remained in excellent condition was a sign to some of St. Francis's followers of his intensely spiritual nature. For this reason, one of the standard representations of this saint is as a corpse reclining and dressed in a cassock or vestments. Such a statue is the focus of pilgrimages to Magdalena.

However, San Francisco has undergone some remarkable transformations in northern Sonora. In the first place, many of those who attend the annual fiesta held in his name now feel San Francisco and Father Kino to be one and the same. Both, after all, were famous missionaries; both are dead. Why shouldn't the statue of the dead man in the church be a representation of the dead man whose bones have been on public view in the middle of the plaza since 1966, where Father Kino's grave was discovered and opened? As a result of this discovery, which followed an intensive investigation sponsored by the Mexican government, Magdalena was officially renamed Magdalena de Kino. In addition, a small dome was built over Father Kino's excavated grave, which is on permanent view in the plaza renovated in his honor.

Nor is that the only way in which Magdalena's cult of San Francisco is unusual. While the feast of Saint Francis Xavier in the Catholic calendar is December 3, the fiesta in Magdalena is celebrated on October 4, the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi. This further confusion is probably a result of the historical fact that in 1767 the Jesuit order, of which Father Kino was a member, was expelled from all the Spanish dominions and was replaced in northern Sonora by the Franciscans. The members of this totally different organization had as their patron saint another Francis - Saint Francis of Assisi. The ensuing confusion in the dates of the Magdalena fiesta is easy to understand.

These details matter little to the thousands of pilgrims who flock to Magdalena each year, visiting their saint and then engaging in the sort of social and economic activity that calls to pilgrims - and secular tourists as well - the world around. They buy souvenirs, eat, drink, and listen to strolling musicians, and generally cap their religious journey with a thoroughly secular good time. The Fiesta de San Francisco in Magdalena is one of those occasions when the traditional cultures of the region are at their most visible, when the region's history is at its most accessible.

Dr. James S. ("Big Jim") Griffith

"Legends and Religious Arts of Magdalena de Kino"

"Southern Arizona Folk Arts"

Kino Monument Plaza - Magdalena de Kino, Sonora

National Monument of Mexico

Pilgrimage to Magdalena

Bernard L. Fontana

To View and Download

"Pilgrimage to Magdalena"

Click Pilgrimage to Magdalena

The first page displayed when downloaded is the last page of the article.

"The Magdalena story is exciting proof that human events

- the river of history - flow in an infinite stream."

Dr. Bernard L. ("Bunny') Fontana

"Pilgrimage to Magdalena"

American West

September - October 1981

Camino de Kino

Pilgrims Walking on Highway 15

From Nogales to Magdalena de Kino

Prayerful Pilgrimage

Tim Steller

The long journey starts with a small gesture. Thirty-seven people alight from seven vehicles in Nogales, Sonora, and cut across the highway to a tiny white chapel nearly swallowed by the surrounding factories.

Inside, they kneel to pray. Then 24 of them rise, cross themselves and start walking south.

They will walk for 36 hours across 55 miles of pavement, gravel and sand. The other 13 people, traveling in vehicles, will help them reach their destination: the mission church in Magdalena de Kino.

Arriving there, this Tucson group of family and friends will have fulfilled their - a promise to San Francisco Xavier.

Roberto Lopez made such a promise in 1978. After a newborn relative was given last rites, Lopez promised he would walk to the Magdalena mission if the baby survived. Miraculously, the baby did, and come October that year, Lopez walked.

Lopez, now 48, strode from his house near Reid Park, planning to head out to Magdalena alone. He stopped at his parents' home near Pueblo High School, where his brother-in-law John Robles decided to go with him. Walking day and night for about 120 miles, they made it.

"By the third year, more people came along with us. It kind of snowballed," Lopez says.

Year after year since then, Tucson's Lopez and Robles clans, plus friends and acquaintances, have gathered to make the pilgrimage to Magdalena. They do it not just for religious reasons, but also to renew their bonds with one another, Lopez said.

Striding down the edge of Mexico's Highway 15, they join a dispersed flow of Mexican, Mexican-American, Tohono O'odham and Yaqui pilgrims.

All are taking part in a tradition of Sonoran Desert Catholicism that dates back at least to the 1800s. They walk to the mission churches - either San Xavier del Bac south of Tucson or, more often, to Magdalena's mission - to fulfill a promise or give thanks.

Although thousands walk into Magdalena from all directions, more pilgrims these days drive.

They come for a festival that culminates on Oct. 4, the feast day of San Francisco Asís, the patron saint of the Franciscan order that founded these missions. But the walkers keep their focus on San Francisco Xavier, the patron saint of foreign missions, a statue of whom lies in Magdalena.

For the walkers, their sacrifice - pain - demonstrates their faith.

There is little pain early on in the trek: The walkers are fresh when they start from Nogales at 6 a.m. Thursday, and the weather is cool. Juan Mesquita, at 59 the oldest walker this year, is on cruise control.

Mesquita, of Phoenix, is making his first pilgrimage. When his grandson disappeared for two months this past summer, Mesquita prayed for him to come back. A week later, the boy did.

"Whether that was a coincidence, I don't know," Mesquita says. "But I said, 'I'm going to do it (the walk).' "

Mesquita doesn't agree with those who walk only if God performs miracles for them in advance.

"I'm not about to tell the Lord what to do," he says.

Rather, he and others make a manda, or promise, to walk in hopes that a prayer will later be answered. Often they ask that a sick relative be healed. The walk is a demonstration of faith, not payment for a miracle, Mesquita says.

That concept was a hard sell to Tucson walker Nicole Ayala, 18, after her first pilgrimage.

"The first year I did it for my dad's heart condition," Ayala says. "When I came back (from Magdalena), he was in the hospital.

"I was pissed off. I thought, 'Why the hell did I do this?' "

But gradually Ayala came to see things Mesquita's way. Plus, she found, the sacrifice itself can be a gift - an opportunity for reflection.

"I'm not gonna lie to you. It can be for selfish reasons," Ayala says. "If you don't see during this walk that it's the time God gave you, then you're missing out."

The 24 walkers begin taking advantage of that time south of the Mexican customs station, approximately 11 miles into the journey, as the sun sweeps toward midday. They spread out over a half-mile of the highway's edge, walking in small groups or alone.

Only the occasional crunch of grasshoppers underfoot and stench of dead animals break the conversation and meditation. A cooling wind blows.

About every three miles, the helpers park the vehicles and erect resting stations for the walkers. They set up chairs, pass out water and tend to blistering feet.

Just north of Cibuta, Frank Lopez, Roberto's brother, winces as his sister, Terri Galvez, applies the group's time-tested remedy to his tortured foot.

She soaks a needle and thread in rubbing alcohol, then lances the blister and pulls the thread partway through, so that two tails of thread emerge from the blister. She ties the tails and cuts off the excess thread.

Lopez slips on his socks and shoes, then launches down the road.

"The thread keeps the blister from closing up," Galvez says.

The aid of the 13 helpers is not simply a favor from friends, she adds. They are fulfilling their own manda.

"To me, it's equally as important as walking," Galvez says.

Others who cannot make the pilgrimage park alongside the highway and hand out food and water to walkers they do not know.

After 28 miles of walking Thursday, Ronnie Molera is the last one to arrive at Rancho Aguascalientes, the Tucson group's overnight resting place. Roberto Lopez accompanies the last arrival, as he always does.

Blood blisters cover the 23-year-old Molera's feet, which he soaks in a tub of water mixed with a disinfectant. Then he crashes in a sleeping bag while the others eat spaghetti and drink beer. The next morning he wants to walk.

"They're telling me not to do it," Molera says. "But that gives me more motivation."

Without a signal, the walkers trail out of camp at around 5 a.m. For the first hour, they walk in darkness, carrying flashlights to alert drivers. The world is silent except for a cold wind that later bears dawn.

For Ernie Sanchez, this is the start of a sacred time.

"The first day (of walking), I prepare for the second. The second day, I pray - all day," Sanchez said.

The walkers descend gradually to Imuris, a crossroads town where they leave the highway. The midday sun bakes the town and reflects off its whitewashed façades.

At lunch there, Aaron Valencia, the victim of a chronically injured knee, leaves the walkers and joins the helpers.

He has been wearing a hat covered in pinned-on trinkets, known as or miracles. A baby's booty represents hopes for the baby his girlfriend is expecting in April.

He had planned to walk to the church and pin the trinkets on the saint's robe. But his injury does not mean his prayers are powerless.

Another walker, Juan Robles, puts on Valencia's hat so the milagros can finish the pilgrimage.

After bathing in the Río Magdalena, the walkers push along a dusty road among fields of cabbage and radishes.

Ronnie Molera, leaning on a 6-foot walking stick, drops further behind. His feet have blistered over again, and the new blisters have popped. His hips ache, his thighs ache and his knees ache.

"I knew it was going to hurt, but I didn't know it was going to be like this," Molera says.

But he has a strategy for moving on, after more than 50 miles of walking.

"I visualize everybody I'm doing this for. I'm carrying them, and that's why I'm going so slow," he says.

Drivers and pedestrians on the approach encourage him, each with the same words: "Ya mero" - "almost there."

The walkers pass down Magdalena's Avenida 5 de Julio after dark, arriving in the town square amid the bewildering swirl of Friday night festivities. They exchange hugs, then they walk - avoiding cobblestones - to the little side chapel where the statue of San Francisco Xavier lies.

There, they pin milagros on the recumbent statue, caress it and kiss it.

Although he has run five marathons in his 59 years, Juan Mesquita can barely walk.

"Thank you, Lord," he says. "It's done."

Magdalena De Kino, Sonora.

Tim Steller

Arizona Daily Star

October 4, 1998 Page: 1A

Paul Cicala and Bronson Smith on the Camino de Kino

The Pilgrimage in Film

La Fiesta de San Francisco Javier - Magdalena de Kino

The Magdalena Pilgrimage and Fiesta

Sergio Raczko

Documentary

In Spanish

Click

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWtt0Gvek1Y

Pilgrimage to Magdalena 2014

Paul Cicala

TV Program

News Program runs for first 4 minutes

Extended Film Footage for next 6 minutes

KVOA TV - Tucson

In English

Click

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVgM6mf5xds

Magdalena de Kino, Sonora

The Pilgrimage in Contemporary Song

"Magdalena"

Brandon Flowers

Singer / Songwriter

Heartland / alternative rock star Brandon Flowers wrote the song "Magdalena." He sings "Magdalena" on his hit 2010 solo album "Flamingo." Flowers told Rolling Stone magazine that "Magdalena" was inspired by a documentary about the Magdalena pilgrimage.

Flowers' song is about the last 60 miles of the pilgrimage route in Mexico from Nogales, Sonora to Magdalena de Kino. Many pilgrims begin their journey at Mission San Xavier del Bac in the United States and cross the United States - Mexico border.

"Magdalena" with acoustic guitar accompaniment

Click

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TA84NSp-hdU

"Magdalena" from Brandon's "Flamingo" album with scrolling lyrics

Click

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vXrc4f8BZs

Pilgrims' Prayer Intentions Pinned To

Reclining Statue of St. Franics Xavier

Mission San Xavier del Bac, Arizona

Pilgrimage to San Xavier

Bernard L. Fontana

To become a pilgrim is to embark on an adventure, to leave the comfort and security of one's home, neighbors, and familiar surroundings as an act of faith. It can be motivated by the need to do penance. It may be Inspired by a sense of thanksgiving. It can be a sacrifice offered in petition.

A pilgrimage must, however, have a sacred place as its goal.

The tradition of pilgrimage is as old as organized religion. And the custom is alive and thriving in southern Arizona where Mission San Xavier del Bac, founded in 1700 by Jesuit missionary Eusebio Kino, has become the magnet for peregrinos, pilgrims, who walk to the mission, hundreds of them each year.

The journey has to be on foot. Driving or riding doesn't count.

The Mission San Xavier we see today was built by Franciscans between the late 1770s and 1797. It is the parish church for Papago Indians who live on the San Xavier Indian Reservation; it is one of Arizona's most popular tourist attractions; and, beginning possibly as early as the last century, it has become a center of pilgrimage for many of the region's Mexicanos or, Americans of Mexican descent who are bearers of a Christian tradition rooted in antiquity.

The mission is located about nine miles south of downtown Tucson. On any day of the week, but especially on weekends, pilgrims make their way south along Mission Road or east along San Xavier Loop Road toward the church. They walk singly, in pairs, trios, or in larger groups. Their heads are uncovered, or they wear wide-brimmed hats, baseball caps, or bandannas. A few wear the religious habit of a saint or sectarian figure. Some carry umbrellas. They may carry water bottles and be without visible logistical support. Or they may walk ahead of a car or truck that will park, then catch up again every few hundred yards. They walk unaided, although some use walking sticks, canes, even crutches.

The pilgrims are of all ages: young children who are hardly more than toddlers, boys and girls, young men, women - some with babies in arms - middle-aged, and elderly. Some stand erect; others are stop shouldered. Some walk briskly; others, idly, playing as they go and aiming rocks at rabbits or birds in the brush beside the road; still others shuffle along, painfully determined to make it all the way to their destination. There are those who laugh, smile, and talk. There are those whose countenances are grim, sad, or reflective and who say little or nothing.

They share a common goal. It is to cover the miles on foot to Mission San Xavier del Bac and, once there, to give thanks to God through one of the saints for a blessing received or to petition for a blessing desired.

For some, the walk is not enough. A few elect to give further evidence of their devotion and added meaning to their sacrifice by going the length of the nave or sometimes all the way from the gate at the atrium in front of the church - on their knees. Fewer still throw themselves flat before the high altar.

Many light votive candles in honor of a particular saint (more than three dozen are represented inside the church by images sculptured in the eighteenth century). Many more affix small metallic votive offerings (milagros), usually in the shapes of afflicted body parts, to the coverlet over the reclining statue of San Francisco lying on an altar in the west chapel.

The majority of these pilgrims are carrying out the terms of a vow (manda) made to God through the intermediary of a saint. Others make straightforward requests.

Notes left beneath burning votive candles in the mission's mortuary chapel during a typical month tell part of the story:

"As que me rínda el dinero St. Lazaro." (Make my money stretch, Saint Lazarus).

Or another in translation: Fairest sainted child Atocha [i.e., Christ who appeared as a child and aided the Christians at the time of the Moorish invasion of Atocha, Spain], we give you thanks for all the favors that we have received from you daily. Thank you, adored Child of Atocha, for having helped my little son J. ···· with his left hand and for his having come out of his two operations well and able to use his little hand Many thanks to you. Child of my heart. I promised to dress him like you and I fulfilled my promise for three months, and now I offer you his habit (a beautifully hand-sewn tunic and cape) in the name of my son J…From now on, you will be his advocate; so take of care him, protect him, and guide him on the right path now and forever. Thank you for your miracles and blessings, sainted Child of Atocha.

And in English, written on the back of a voided personal check: Dear God - I am in so much trouble with the law. Please help me be strong and give me thoughts to help me and my family and friends who are going through this. I'm begging you to please help. I don't want to go to prison. And I don't want to be scarred for life. God help me be out of this and let all this be over real soon.

With nearly equal anguish: Dear Sweet Jesus, Sacred Heart. Here I am asking you please to help me in my life, help me with my divorce. Please!

Don't let me hurt anybody! Help me make a better future for me and my kids. I promise to try very hard. Please be with me all the way. Please help my husband not to hurt so much. Help him, please.

Forgive me my sins. Have mercy on me.

Thank you for every blessing you have given us. Please be with me. Give me strength.

I love you.

And most poignant of all: St. Anthony. Please give my baby back. Please.

Pilgrimage. An act of faith, an expression of deeply held religious convictions. And famous, beautiful Mission San Xavier del Bac is the goal. It is a holy place in which to receive affirmation of one's innermost sentiments, whether of penance, thanksgiving, or petition - a place that provides beauty to the eye and sustenance for the soul.

Dr. Bernard L. Fontana

Pilgrimage to San Xavier

Arizona Highways

November 1986

To View and Download

"Pilgrimage to San Xavier"

For the article's original format, the entire Novermber 1986 issue of Arizona Highways Magazine must first be accessed on the Arizona Memory Project's page for that issue.

Click

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/37202

Then click on the pdf icon on the issue page that is to the right of the Novermber 1986 issue front page image. The front page image is on the left side on the page. The article is at the back on pages 44 - 48