Kino Wheat

Food and Seed Provider

Kino Wheat Harvest at BKW Farms

Along Kino's Santa Cruz River Trail

Annual Kino Wheat Celebration

Commemorating Kino's Bringing Wheat and Food Security

Plant - November through January

Grow, Harvest and Share - May

Kino is revered as the Patron Saint of Wheat by the many who believe that he is a saint. His formal cause for sainthood is currently under consideration by the Vatican.

Kino grew wheat for the hungry native peoples of the Sonoran Desert. He gave them wheat to eat and also shared wheat seeds when the O'odham traveled year round to his missions to help Kino plant, harvest and roundup and to receive his ministry. Kino also brought these gifts on his 50 expeditions beyond the Spanish frontier. His pack trains were laden with seeds and plant cuttings for the O'odham and the Native People of the Colorado River Valley. Kino usually traveled with 50 to 75 pack animals but sometimes there were one hundred.

Seed sharing was a very important part of the introduction by Kino of European fruit and vegetable crops and grains to the Sonoran Desert. Kino's gifts, especially wheat seed for both eating and growing, provided food security at times of the year when streams ran dry and desert food sources were scarce. Kino established the wheat culture that survives today in our region that includes the thinnest wheat tortillas in the world, Sonoran pastries and pozole de trigo.

Join with other Arizonans and Sonorans who annually honor our santo of wheat with a living tribute. Plant Kino Wheat (White Sonoran Wheat) in the the months of November and December and January. Plant in containers, tree wells, home gardens or farms. Or just plant in a small patch of ground, Kino wheat can grow well with little water and no fertilizer. Then in May join the harvest celebration which coincides with the regional Kino Festivals that commemorate of the anniversary of the discovery of Kino's skeletal remains on May 21, 1966 in Magdalena, You can cook your harvest. Or you can share and donate you wheat seed to your local seed library or to the Seed Library of the Pima County Public Library.

Kino’s heroic life and enduring legacy is honored by the display of his skeletal remains in the mausoleum located in the town square of Magdalena de Kino, The mausoleum was built over the exact place where Kino's skeleton was discovered by an international team of scientists on May 21, 2016. Since Kino's death in 1711, Magdalena has been a site of religious pilgrimage and tourism especially during the weeks in late September before October 4th feast day of the three Franciscos of the Pimiería Alta.Throughout the region other communities in Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora join in solidarity with the Kino Festivals.

The discovery of Kino's grave has been described as miraculous and its story with its twist and turns reads like an archeological detective story. For more details, click Grave and then Chapel.

Kino Wheat is one of the oldest surviving heritage wheat varieties. Historically its sustainable dry-land production made Arizona's Gila River Valley and California's Central Valley the breadbaskets of the West until it was supplanted by "Green Revolution" hybrids. It was saved from extinction by the Native Seeds/Search and has been grown during the past years for seed banking by community organizations and by family farmers like BKW Farms.

Kino Wheat's heritage growing characteristics include drought tolerance, preference for low fertility alkaline soils, disease resistance and easy to remove seed husks. It has a sweet flavor especially good for baking. It is low in gluten and has good protein content. It is also known as Triticum aestivum, White Sonora Wheat, Sonora Blanca and in the O'odham language as Pilcañ. In the Sonoran Desert, Kino Wheat is planted in the months of late Fall and early Winter and is harvested in late May and early June. It is planted as a spring wheat in colder climates.

Join the annual celebration and honor our santo of wheat and help support the revival of Kino Wheat that will again become a very important food crop grown in the Western United States.

Also join the annual Tumacacori Festival held at Tumacacori National Historical Park in the first weekend in December. The Festival began in 1966 to commemorate Kino's first visit to Tumacácori and today's state of Arizona. Kino named the village of Tumacácori in honor of San Cayetano, the European patron saint of wheat givers. For more about Kino and San Cayetano, click San Cayetano. San Cayetano's saint's day is August 7th.

Threshing Wheat at San Xavier

Early 1900s

Kino's Introduction of Wheat Provides Food Security

… O'odham subsistence also confronted iron limits imposed by the seasonality of desert rains and the plants and animals that depended upon them. Late spring and early summer were often times of sever hardship — day after long, hot day when people waited with hungry bellies for the clouds to form, the mesquite pods to ripen, and the corn and bean plants to mature. …

Because it tolerated frosts, wheat "pilkañ" in O'odham, filled a largely empty niche in the agricultural cycle, growing during the winter months when corn, beans, and squash would have withered. O'odham could now double-crop their fields, planting wheat in November or December after their summer corn and beans had been harvested. "Pilkañ" matured in May or June at a time when mesquite pods had not yet ripened and spring maize and bean plants were still struggling to grow. …

"Many of the new crops were additive," [Amadeo] Rea notes, "but wheat largely eclipsed maize as the basic crop. Wheat tortillas became the staple at most meals; even the oldest people today cannot remember anyone making corn tortillas. Wheat replaced corn and mesquite flour in many preparations as well. Wheat pinole (parched and finely ground wheat) became a staple for both those traveling and those at home. It needed only to be mixed with water to make a hearty cereal drink."

Despite wheat's importance, however, the O'odham often combined it with aboriginal foods, particularly mesquite flour. Mesquite and wheat flour were blended to make a sweet pudding called "vihog hidod." The O'odham also made a dish called "ka'akvulk" (hills made), wheat tortillas alternating with layers of mushy mesquite. O'odham men carried" ka'okvulk" on hunting trips or revenge raids against the Apaches. Mesquite flour ("vihog weenagim chu'i") sweetened wheat pinole whereas whole wheat dumplings (doves) simmered in mesquite juice ("hooi-wichda:" mourning doves done in imitation) (Rea 1997).

Dr. Thomas E. Sheridan

"Landscapes of Fraud: Mission Tumacácori

The Baca Float and the Betrayal of the O'odham" 2006

Winnowing Wheat in the Wind - Early 1900s

Wheat Harvest Moon - New Year of Akimel O'odham

The Akimel O'odham were even more intertwined with the politics of water control in the American West. In the precontact period, the Akimel O'odham, unlike the Tohono O'odham, did not have to migrate between winter villages and summer camps. On the contrary, they lived in more-or-less permanent settlements along all the major rivers in the Sonoran Desert, including the Dolores, the Magdalena, the Altar, the Concepcion, the Santa Cruz, the San Pedro, and the Gila. As a result, both their fields and their villages were larger than those of their Tohono O'odham brethren.

Nonetheless, the Akimel O'odham did face one major limitation: the lack of a major food crop that could be grown during the winter months, when frosts were a danger. Corn, beans, and squash - the staples of their diet-withered when the weather turned cold. In the upland areas, the River Pimas were able to cultivate their fields only from March through October, a constraint that restricted the size of their communities and their ability to depend on agriculture.

When Jesuit missionaries like Eusebio Francisco Kino began to visit the Akimel O'odham in the late 1600s, they brought gifts of Old World livestock like cattle and horses and Old World crops like winter wheat. Wheat, in fact, revolutionized Akimel O'odham society because it gave them a major cultigen that could be planted in November and harvested in June by filling a gap in the agricultural cycle, wheat allowed the River Pimas to farm year-round. That in turn enabled them to live in larger, more permanent settlements, an important defensive measure as Apache raiding intensified in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Wheat became so important to the Pimas along the Gila River that some even began to call the first month of the year Wheat Harvest Moon instead of Saguaro Harvest Moon (Ezell 1961; Russell 1975).

Wheat also turned the Gila Pimas into the first agricultural entrepreneurs in Arizona. During the war between Mexico and the United States, the Akimel O'odham traded both corn and wheat flour to the U. S. Army. After the war ended and gold was discovered in California, thousands of "argonauts" trudged through Pima villages along the Santa Cruz and Gila on their way to the goldfields, stimulating the Pirnas to intensify production and expand their acreage. The market continued to grew with the establishment of a stagecoach route through Pima territory in 1857 and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. By 1870, Akimel O'odham along the Gila River were selling or trading several million pounds of wheat a year. Pima fields had become the breadbasket of Arizona Territory. In recognition of their importance, the federal government created the first Indian reservation in Arizona for the Akimel O'odham and their Yuman-speaking Maricopa neighbors in 1859. Known as the Gila River Indian Community, it was enlarged seven times between 1876 and 1915 until it encompassed 371,929 acres.

But the crucial resource in central Arizona was water, not land. It is interesting to speculate about what might have happened if Pima water rights had been respected. O'odham canals might have rivaled those of the prehistoric Hohokam. ThePimas might have diversified into milling, freighting, and stock feeding as well. But that was not to be. Beginning in the late 1860s, Anglo farmers began settling upriver along the Gila inthe vicinity of Florence and Safford, digging canals and diverting the water of the Pimas. Crops failed and fruit trees withered.

In 1873, Antonio Azul led a delegation of Akimel O'odham toWashington, D.C., to protest the situation. The government responded by suggesting that the Pimas move to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. The Pimas refused, but 1,200 did migrate north to the Salt River, where irrigation water was available. The Salt River Indian Reservation was set aside for those migrants, including several communities of Maricopas, in 1879. The rest of the Akimel O'odham fanned out along the Gila and farmed as best they could along stretches of the floodplain where water still flowed.

Then in 1887 the construction of a large canal near Florence diverted the Gila once and for all. By 1895 conditions were so desperate that the government had to issue rations to the Pimas. Pima calendar sticks, which had recorded floods and Apache attacks three decades before, now said, "There was no crop this year," or, "This year there was no water." In the span of a single generation, the Akimel O'odham had been transformed from prosperous independent farmers into poverty-stricken wards of the state. Once they had produced enough food to feed the territory; by the turn of the century they did not even have enoughwater to grow food for themselves.

Dr. Thomas E. Sheridan

"Akimel O'odham Agriculture: From Abundance to Desolation"

in "Paths of Life: American Indians of the Southwest and Northern Mexico" 1996

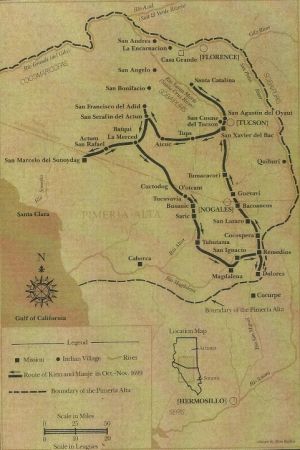

Kino Expedition Map

University of Arizona Kino Diary

Seed Sharing With Native Peoples of the Colorado River

"Also I went in as far as San Marcelo, whence, by the captain of El Comae, I sent wheat to sow at the Colorado River and in the Yuma and Quiquima nations, grain and seed which had never been seen or known there, to see if it would yield there as well as in those other fertile new lands; and it did yield and does yield very well."

Eusebio Franicisco Kino

Chapter 3

Of Two Other Journeys Inland Which I Made To The West And North,

Looking To The Spiritual And Temporal Welfare Of The Poor Natives

Part 1 Book 5

Favores Celestiales

Bread Horno (Oven)

Mission San Xavier del Bac 1894

Kino Wheat and Seed Notes

In the mid Fall of 1699, Kino riding 675 miles in 25 days met with the O'odham in their villages located through out today's O'odham Nation. Over 1,800 desert sharing O'odham people welcomed Kino and other members of his expedition. In the last 5 days Kino with sometime trail companion Juan Mateo Manje separated from the others and rode over 300 hundred miles while Kino ministered to both earthly and spiritual needs and took noon day sun sightings with his field astrolabe for the preparation of maps.

At San Marcelo (today's border community of Sonoyta) Kino sent wheat seeds to the peoples of the Colorado River who he had not yet met. The following day and night Kino and Manje rode about 75 miles to rendezvous with other expedition members at Búsanic. Kino averaged 27 miles per day on horseback during the entire 25 day expedition.

Within the next 2 years Kino would make 3 expeditions to the Colorado River and be welcomed by its people. One trip Kino arranged for food relief from the Quiquimas to their traditional Yuma enemies. The crops of the Yumas had failed and they were near starvation, On his last trip to the area Kino would travel to the Colorado Delta and discover that California was not an island as them commonly believed. His findings reflected in his 1701 map gained Kino fame as a heroic explorer and historically important cartographer.

Kino in his diaries and letters to his superiors always reports on the status of the wheat crops at his missions and visiting stations and the help he received from the O'odham especially from the village of San Xavier de Bac who would travel a hundred miles to his Dolores mission headquarters to help him plant in the Fall and harvest in late May and early June.

For more information on this expedition (Expedition 24) and other Kino journeys to the Colorado, click Explore Colorado River and Delta

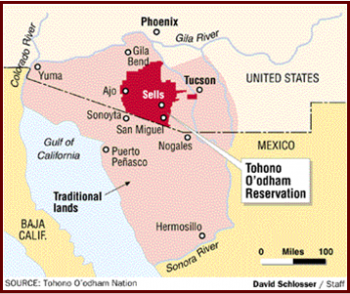

O'odham Traditional Homeland Map

Raising Hell as Well as Wheat - Papago Indians Burying the Border

Gary Paul Nabhan

Isidro Saraficio is sitting in a dry irrigation ditch, under the shade of a Mexican elderberry tree, gazing out over a wheatfield wavering in the noonday heat. It's a fine stand of wheat for a desert field grown with just the rain that ran down the arroyos this winter. Isidro diverts floodwaters from a holding pond to the field through hand-dug ditches, letting gravity rather than machines do the work. Now that the grain is ripe, his friends have come to the rancheria to help with the harvest. ….

The quiet of noon is suddenly ruptured. Like a giant raptor, a Border Patrol plane breaks into sight and roars down across the land a few hundred feet over the field, causing quail and doves to flush out of the wheat. The patrolling plane zips westward, straight above the fence line and firebreak that stretches as a scar all the way to the far horizon. Sitting up as if awakening from a bad dream, Isidro's friends realize that the nightmare sound they heard is part of his everyday world. The field lies within a mile of the U.S./Mexico border.

Isidro planted the wheat not only for pinole and popovers, but also as a political protest. He was born here on the ranch in Sonora, Mexico, when the elderberry above him first came into bloom thirty-four years ago. Yet his family has never had a deed to this place, which they have probably farmed for hundreds of years. Isidro has planted wheat on land that another man "legally" owns. The field has been worked to show that the homestead has not been deserted. …

In short, Isidro is raising hell as well as wheat. He is raising his sickle to question the existence of a boundary that his people have never acknowledged.

Isidro is a Papago Indian, sharing this borderland dilemma with 10,000-15,000 of his people who refer to themselves as the Tohono O'odham. …. In 1853, a political decision made thousands of miles away divided the Papago country between the United States and Mexico.

Gary Paul Nabhan

The Desert Smells Like Rain: A Naturalist in O'odham Country

Chapter 2

Raising Hell as Well as Wheat: Papago Indians Burying the Borderline 1982

Don Guerra, Owner of Barrio Bread

Great Breads from Kino Wheat and Other Locally Grown Grains

Organizations and Online References

Where to Purchase Kino Wheat - Seed, Bread & Other Products

Barrio Bread - ARTisan Breads

Tucson, Arizona

Community Based Baker

Top Ten Bread Bakers of America - 2016

Click Barrio Bread

BKW Farms

Marana Arizona

USDA Organic Certified Farm

Kino Wheat Grower and Other Produce

Click BKW Farms

Recipes & History

Click

Recipes

Martha (Muffin) Burgess

Flor de Mayo

Ralph Wong - 3rd Generation Farmer

BKW Farms - Marana Arizona - USDA Organic Certified Farm

Kino Wheat Seed Saver & Grower

Kino Wheat Revival Story

Click

SARE Grant Supports Successful Reintroduction of Heritage Grains

Native Seeds/ SEARCH

Summer 2014

Planting and Growing

Click

How To Grow White Sonora Wheat

Artistic Gardner

Simple Planting Notes

This article is great background information but all that is required is:

For Home Gardeners.

In the ground or tree well: just rake the soil, broadcast the seed and cover lightly with no more than one-half inch of soil and then water

In containers: plant 10 to 20 seeds and then water.

Germination: Between 7 to 10 days

Watering: once a month or less if your signing to the clouds brings down the rain down from the sky.

For Farmers: scroll down the page to Technical Information.

Harvesting

Click

White Sonora Wheat – Perfect Grain for the Home Gardener

Underwood Gardens

Simple Harvesting Notes

Thresh by rubbing off husks with fingers

Pick out the seeds or winnow the seeds from the chaff in the wind or with a fan.

Let the stalks (spikes) dry completely and shake out the seed kernels.

Keep the stalks intact for a beautiful holiday floral arrangement.

Share the wheat stalks on San Cayetano's feast day as is the tradition in Argentina. San Cayetano is the patron saint of wheat and the country of Argentina. Kino named the first Tumacacori mission in his honor. San Cayetano's feast day is August 7th. Give the stalk to someone who isn’t having the best luck in the world or give it to somebody as a wish of good fortune. Tell them to hang the stalk on the inside of the front-door of their home for the blessings of San Cayetano and Padre Kino. Click San Cayetano.

Kino Wheat Garden - Kino Historical Society

Milpitas Community Urban Farm - May 2015

Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona

Community Gardens & Urban Farms

Community Gardens of Tucson

Growing Community Through Gardening

Click

Community Gardens of Tucson

Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona

Click

Milpitas de Cottonwood Community Urban Farm

Padre Kino's Favorite Meat Loaf

Community Food Bank Cookbook

"History that you can eat"

Donate To Fight Hunger

Continue Kino's work of fighting hunger and building networks of food security for the hungry through advocacy, food distribution, sustainable agriculture and education.

Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona

Click

Food Bank Home Page

Community Gardens and Community Building

Click

Milpitas de Cottonwood Community Urban Farm

Donate to Seed Library

Help support Kino Wheat and other community based & sustainable agriculture.

Seed Library

Pima County Public Library

Telephone 520 791-4010

English

Click

Seed Library

Click

How to Donate

Spanish

Click

Biblioteca de Semillas

Technical Information

Cooperative Extension

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

University of Arizona

Click

Wheat Growth Stages in Relation to Management Practices

Shawna Loper

Click

The Last Irrigation for Wheat and Barley

Mike Ottman

Extension Agronomist

For Additional Kino Agriculture

Click Farmer Rancher

Click Mission San Cayetano de Tumacacori