Kino - Speaker of Truth to Power

Ride for Justice and Peace History

CORRESPONDING SUBJECT PAGE LINKS: Click on the links below to the corresponding subject pages that presents Kino's 12 year advocacy for the return to The Californias and a daily itinerary of his ride to Mexico City and return with thematic essays. To view the corresponding pages, click Tumacacori page and Kino Ride for Justice Journeys page.

Kino's Ride for Justice and Peace

Speaking Truth To Power

1,500 Miles in 53 Days to Mexico City

Kino's Ride on Horseback from Mission Dolores to Mexico City

[The] cause that has contributed to these deaths, riots and outbreaks has been the constant opposition to the Pimas which in turn has been founded on sinister suspicions and false testimony as well as on rash judgments because of which many unjust killings have been perpetrated in various parts of the Pimeria. ... The Pimas have been viciously and unjustly blamed for the thefts of the livestock and the plunder of the frontiers. ....it is evident that the treatment of the natives in the Pimeria has been very unjust — leading as it has to mistreatment, torture and murder.

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Kino's Biography of Father Saeta 1696

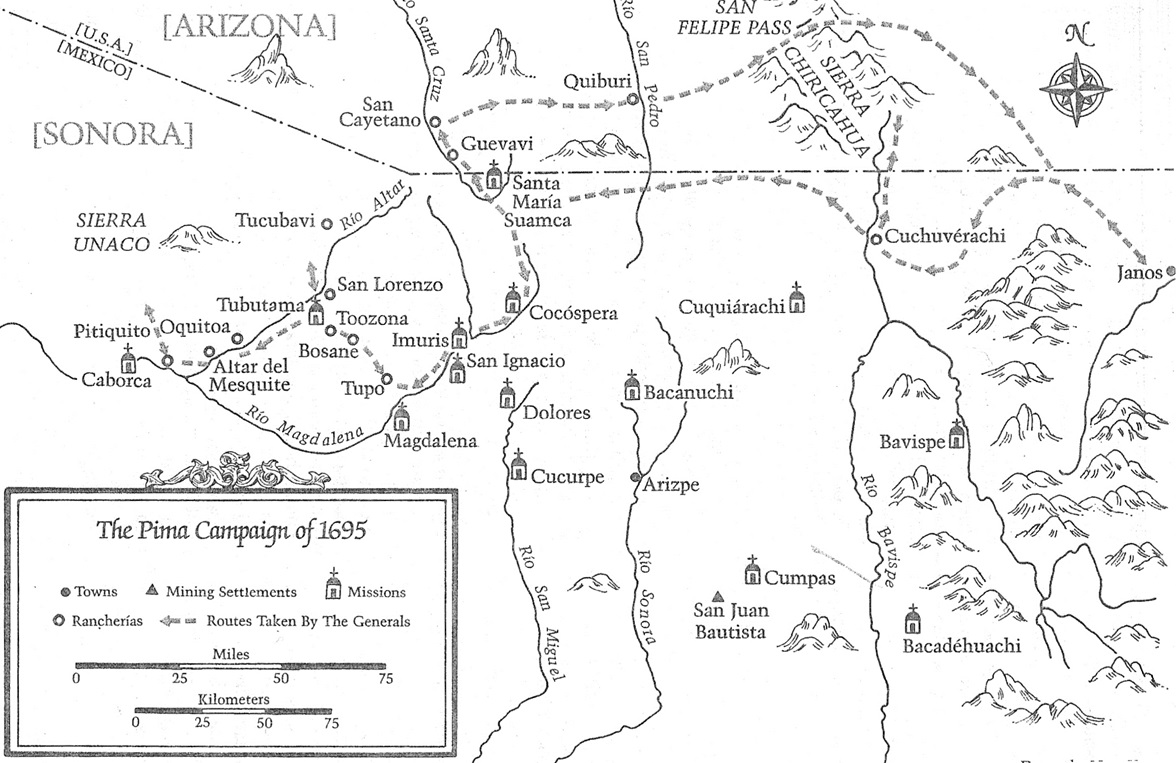

Decisive Years for Pimería Alta 1695-1696

Ernest J. Burrus

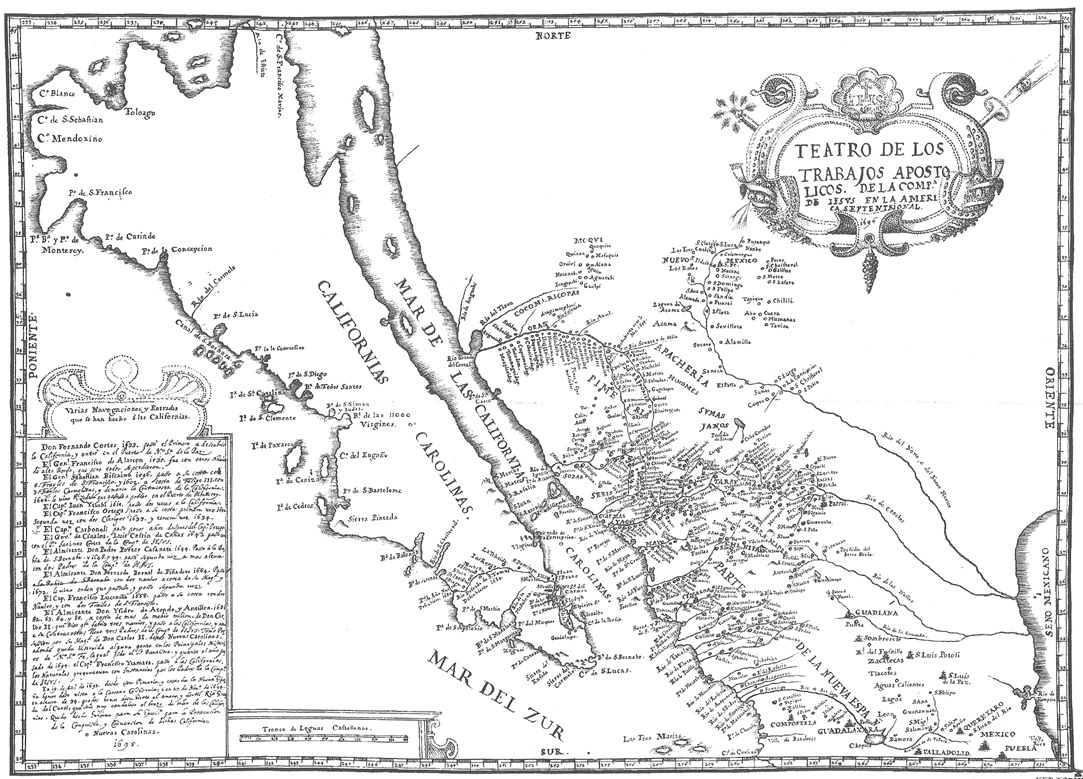

Kino's 1695 Teatros Map Illustrating His Saeta Biography

With Kino's History of Previous Attempts To Settle The Californias

Kino Welcomes Saeta and Discovers Casa Grande

Kino discusses the trip with Father Francisco Javier Saeta in two of his books - in the general diary and in his biography of the missionary. [1a] When Saeta chose Nuestra [72] Señora del Caborca as his mission center, forty-four leagues (one hundred and ten miles) due west of Dolores, Kino offered to accompany him and introduce him to his charges. The veteran missionary generously gave to the newcomer one hundred head of cattle, a like number of sheep, a drove of twenty mares with their foals and studs, draft mules, riding horses and mules, sixty "fanegas" of provisions, and house furniture. Kino had begun the construction of a large church and a suitable residence. He also donated a portable altar, hosts, wine, and all else that was needed for Mass and other services.

Kino and Saeta set out from Dolores on Tuesday, October 19. A ride of twenty-five miles brought them to Magdalena, where they spent the night. The next day they continued on to San Bartolomé via Santa Marta. On October 21, they reached San Pedro del Tubutama in time for a siesta. Before sundown they entered San Diego del Pitquín, a dependent mission station of Caborca. The natives of both missions received Kino and Saeta jubilantly with crosses and arches. With a missionary in Caborca, only twenty leagues from the Gulf of California, Kino felt that another and significant step forward had been made in his return to Lower California.

Kino remained in Caborca until Saturday, October 23, when he started back to his home mission of Dolores, traveling via San Pedro del Tubutama.

Kino, accompanied by some of his servants and native officials, set out from Dolores in November of 1694 to investigate the Casa Grande area forty-three leagues to the northwest of San Xavier del Bac. When Manje was in Cups in June of the same year, the natives told him about some large houses to the north; the officer, in turn, informed the missionary, but, because of the Apache raids, he could not personally [73] participate in an expedition that so fascinated him." |2a| Kino recorded that these large structures "are along the large-volumed Gila which flows out of New Mexico and has its source near Acoma." This is an almost verbatim citation from Manje's entry. Kino did not forget to include this information on the earliest extant map drawn after the expedition, the superb "Teatro de los Trabajos Apostólicos " of 1695-1696. |3a|

Kino did not compile a detailed day-by-day account like those by Manje. About the long ride from Dolores to the Casa Grande area he does not say a word. His first mention is that of El Tusonimo - renamed by him La Encarnación - where he said Mass on the first Sunday in Advent, November 28, 1694. Gathered there were many other Indians from the ranchería of El Coatoydag, further west, named by him San Andrés.

The Indians from these two settlements were, according to the missionary, "all affable and docile people," who told him about two friendly nations living further on, along the Gila to the west, on the Azul to the northwest, and on the Colorado much further to the west. He learned their names - the Opas and the Cocomaricopas. These new nations will henceforth find frequent mention in his diary, letters, plans, and maps. |4a| He will also, of course, visit them and plead for them. He learned that their language was very different from Piman; he found it very clear. As there were some natives who spoke both, he compiled" with ease" ("con facilidad") a vocabulary of the new language. He sketched a map of these lands with the data to be incorporated in all subsequent cartographical productions, determining the latitude for it with an astrolabe.

Kino then describes the "casa grande": a four-story building at the time, "as large as a castle and about the size of the largest church in the Sonoran province." He knew about [74] the legend that Moctezuma and the Aztecs, hard pressed by the Apaches, left their home in the west for these large houses and then later traveled southward to found the city of Mexico. Close to the main casa grande there were thirteen smaller houses, which in Kino's time were already considerably dilapidated; from these and the ruins of many other houses, he concluded that "in ancient times there had been a city here." He also reasoned from the presence of ruins and numerous objects ("metates," jars, and charcoal) that in this area were located the famous cities of Fray Marcos de Niza. He concluded his brief account by observing that "the unconverted and Christian Pimas, the Opas, and the Cocomaricopas remained profoundly consoled" by his visit among them.

In 1694, about to end, Kino had undertaken five expeditions with the notable achievements.

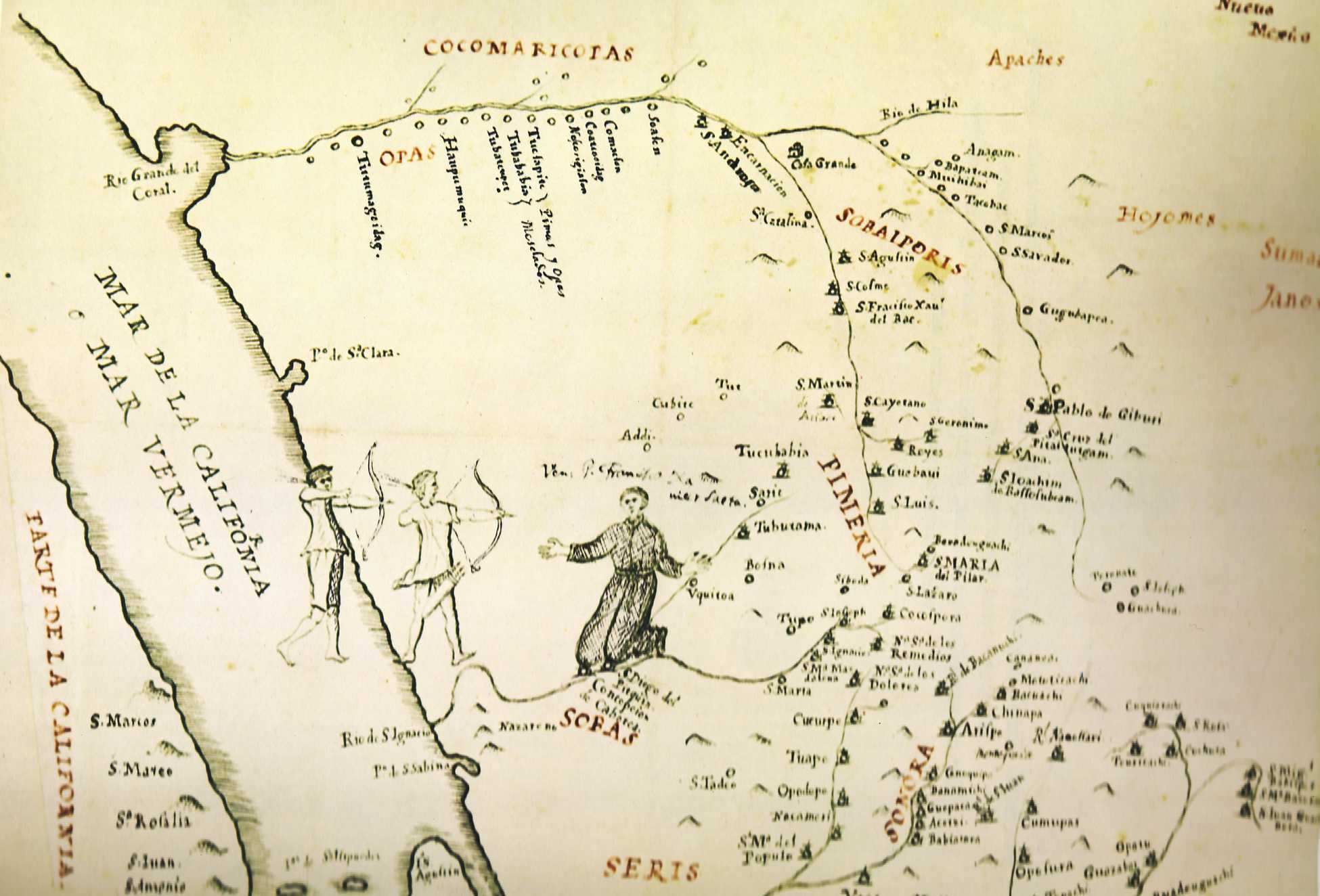

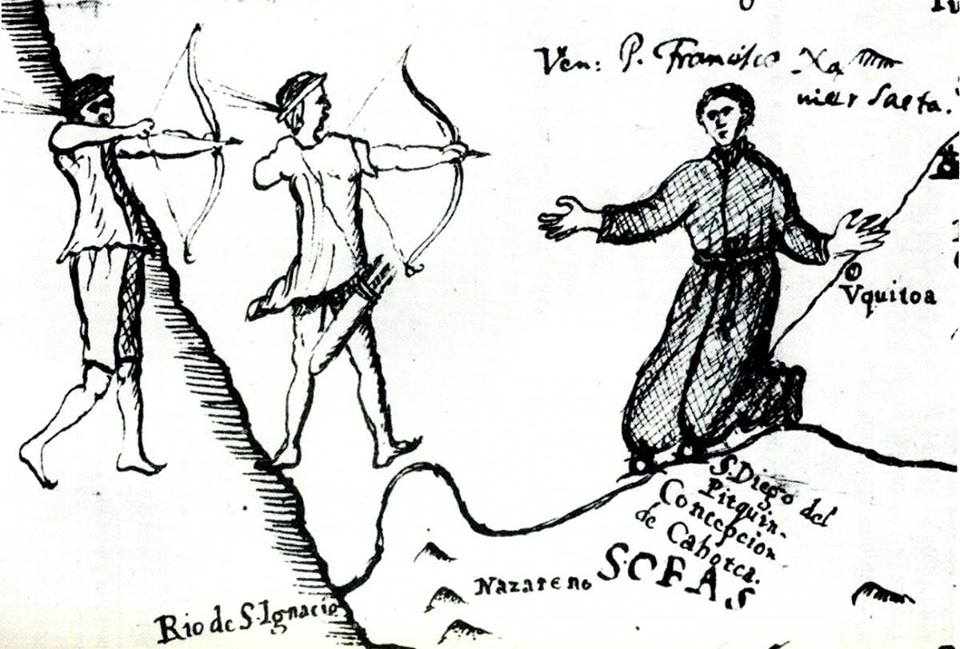

Kino's 1696 Map Illustrating His Saeta Biography

With Kino's Drawing of Father Saeta's Death

Tubutama Uprising and More Deaths in The Western Pimeria

We saw that, in October of 1694, Kino accompanied the new missionary, Father Francisco Javier Saeta, from Dolores to Caborca in order to introduce him to his flock and to initiate him in the spiritual ministry of his vast parish.

Kino designated servants, interpreters, a catechist, a cook, a herdsman, and other assistants to help run the mission. A flourishing garden soon sprang up around Saeta’s residence. The new missionary taught the Indians not only their catechism through the interpreters and the catechist, but also how to till their fields, raise cattle, and construct better homes.

Kino’s generous financial assistance, however, was not sufficient for all that Saeta wished to have for his missions at and near Caborca, especially because of the extreme poverty of the natives. Hence he set out, in mid-November of 1694, accompanied by several Caborcan Indians, to beg alms in some of the earlier Jesuit missions in Sonora, journeying in all some six hundred miles. In December of 1694, Kino met Saeta in Arizpe as he himself was on his way to Mexico City. Kino, however, would have to delay the trip for some time because General Jironza, the military governor, wished him to remain in Pimería Alta while preparations were being made against the marauding Jocomes, Janos, and Sumas.

By the end of January of 1695, Saeta had come to Kino’s home mission of Dolores, where they discussed plans for the future and the most effective mission methods. In the meanwhile Kino had sent him more horses and mules. Saeta thanked him in several letters written during March, and reminded him that he was reserving part of the cattle and produce in Caborca for the Lower California missions to be established.

Ominous war cries cut short such bright prospects. On April 1, 1695, Good Friday of that year, Saeta wrote to Kino to tell him that the Jocomes had raided San Pedro del Tubutama — Father Januske, its pastor, was fortunately absent at the time of the attack — and that they had killed several of the natives, among them two of his servants.

The Pimas of Tubutama took advantage of the confusion caused by the Jocome raid in order to kill the hated Opata overseers of Januske and incited the Pimas of the nearby dependent missions of San Antonio de Oquitoa and San Diego del Pítquin to accompany them on an attack against Caborca.

As the sun rose on Holy Saturday, April 2, the Indians entered the missionary’s house, where he received them cordially. As he stood in the doorway to bid them farewell, two of the natives drew their bows and shot him with arrows; they then followed him into the house and, as he lay dying, repeatedly shot him with more arrows. Saeta’s four faithful servants met a like fate.

This was the spark that set the Pimería Alta province ablaze. The almost superhuman efforts of Kino and Manje to pacify the Pimas lies beyond the scope of this volume. [See below sections entitled "Rebellion in the Valley" and "Campaign In Western Pimeria Alta and Commanders"]. The reader will find listed in the notes the key sources on this important episode in the history of the borderlands. The tragic and senseless slaughter of the many innocent along with a few guilty ringleaders in El Tupo, at a place appropriately called “La Matanza,” recalls Atondo’s similar massacre in La Paz, Lower California. The Pimas were not frightened into submission but aroused to rightful anger. At El Tupo the Spanish soldiery had sown a storm and for the next few decisive months were to reap a province-wide whirlwind.

Kino and O'odham Trail Companions Arrive In Mexico City

Part of City Hall Mural in Magdalena de Kino

Kino's Ride for Justice and Peace To Mexico City

Kino was tireless in his efforts to reassure the innocent. As peacemaker, he could draw on his long experience and even more on the general goodwill he had created and accumulated since first coming to them in 1687. The Pimas believed his word and submitted. He knew, however, that the future of Pimería Alta would not be decided in this rim of Christendom but in Mexico City, Madrid, and Rome. This realization determined his activity for the next few months. Unless he could convince authorities in these three centers that the Pima rebellion was not the work of the nation as a whole but of a very few malcontents — most of whom had already repented — the missions in Pimería would be ordered abandoned and might not be re-activated for many years to come. The soldiers would retreat to safer presidios, and the colonists would abandon the mines, ranches, and farms. The Apaches and their confederates would have a free hand to kill and plunder at will. Not only the future of Pimería Alta was at stake, but all the projects for expansion into Lower and Upper California, and into the regions along the Gila and Colorado Rivers.

Hence his decision to attempt to win over the policymakers in the three key cities by hurrying to Mexico City, the most important of the centers from which to fight for his cause. Here he would explain his version of events to civil and ecclesiastical authorities in order to prevent any adverse and irrevocable decision being taken and any unfavorable report being sent to Madrid and Rome. From the abundant documentation he preserved at Dolores, he wrote an account of the recent tragic events and a biography of Saeta, and delineated two superb maps to illustrate the volume. Of all this material he made several copies.

“Setting out from these missions of Sonora on November 16, 1695, in seven weeks, and after a journey of five hundred leagues, I arrived in Mexico City on January 8, 1696,” he recorded in his diary. He added, “It was God’s will that I should be able to say Mass every day of the journey; and three Masses on Christmas I said in the new Jesuit church in Guadalajara. The same day on which I arrived in Mexico City, Father Juan María Salvatierra reached the capital by another route. That very morning Father Juan de Palacios entered as the new provincial.” The Conde de Galve, viceroy of Mexico since 1688, would remain in office until shortly after Kino’s departure for Pimería Alta.

The missionary remained exactly one month in Mexico City. Bolton thus sums up his activity during those days: “While in the capital Kino showed his usual vigor, and succeeded with some of his purposes. He had long sessions with Father Palacios, the new provincial, and conferred personally with the viceroy and members of the Royal Audiencia. He made a heavy assault upon the false charges against and the grave abuses heaped upon the Pimas. As Alegre tells us, ‘He showed that in the recent uprising the guilty parties were some captains of the presidios who were excessively arrogant.’ Solís of course was one of them. ‘He demonstrated clearly the iniquity with which they had outraged the inhabitants of Mototicatzi ’, obtained a decision in their favor, ‘and an order that they should be restored to their lands.’ Finally, he accomplished the primary object of his journey, for the provincial assured him that he should have five new missionaries for Pima Land . . . While in the capital Kino and Salvatierra jointly urged the resumption of missions in California, now ten years abandoned, but at the time they did not succeed.”

Kino, however, accomplished very much else. As we have seen, he finished the biography of Saeta, which was at the same time a defense of the majority of the Pimas, and saw to it that copies of the book got into influential hands. Still more important, he carried on a lengthy correspondence with officials and influential friends in Madrid and Rome. .....

Tirso Gonzaléz, Jesuit general at the time, wrote to Palacios, the Mexican provincial, three letters dated July 28, 1696, which refer to Kino and clearly reflect the missionary’s defense of the Pimas — it is clear that the general has made Kino’s thesis his own. In the first of these messages, he merely informs the provincial that he grants permission to publish Kino’s life of Saeta.

In the second, he obviously makes Kino’s interpretation of the Pima revolt his own. “The rebellion of the Pimas, in which Father Francisco Javier Saeta met with such a glorious death, would cause us to fear for the very existence of those new missions if we listened to the gloomy reports of some persons. According to them the Pimas are of unstable character; they claim that these natives entertain hatred against the missionaries and refuse to settle down to live in civilized towns. But obviously these are reports made by those who are unacquainted with what has really happened. According to the account sent us by Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, the rebellion was the work of a few; and even these are now so repentant that they themselves have helped in apprehending the ringleaders of the revolt and of the sacrilegious assassination of Father Saeta and the three Indian children who served him.” .....

Gonzaléz goes on to propound for the benefit of the Mexican provincial one of the key theses of Kino’s biography of Saeta: “The Gospel has been disseminated only through the shedding of innocent blood. Hence I think that, in the present instance also, the blood of Saeta will produce a flourishing Christian community ” in Pimería Alta.

The general’s third letter is an incomparable defense of Kino’s line of action and of the man himself: “Your predecessor withdrew Father Kino from the missions; the missionary himself has written to me from Mexico City. He has been led to believe that he was summoned to report on the missions and to discuss with the viceroy the means of re-activating the California enterprise. But the letters of your predecessor state that the real motive was to get him out of the missions and keep him in the Province.

“If this is so, I cannot possibly approve such a decision, inasmuch as it deprives those missions of a most devoted worker who has toiled there with untiring zeal and boundless enthusiasm. Such has been his success that were he now employed at other tasks, he should be freed from them, and sent to the missions; so far am I from approving your withdrawing him from them! .....

“Accordingly, your Reverences will allow him to return to the missions. You will let him work there, inasmuch as ‘the just man is not to be hemmed in by any law \ I am convinced that Kino is a chosen instrument of Our Lord for His cause in those missions. ”

Fortunately, Kino did return to the northern missions. Copies of the letter just quoted were sent to his more immediate superiors, who, in consequence of it, did not oppose him as openly. ....

Kino’s most complete plan or project for the development of Pimería Alta and adjacent regions is contained in his life of Saeta. He began working on the biography before he left for Mexico City on November 16, 1695, and finished it before setting out on the return trip on February 8, 1696. His two maps, completed sometime in 1696, record the numerous expeditions he made in Lower California and on the Mexican mainland. .....

The life of Saeta deals with the following topics, listed according to the seven extant books: The first book: the coming of Saeta to Caborca and his pioneer apostolic activity there and in the dependent missions. The second book: the second period of Saeta’s work in the same missions as derived from the missionary’s letters. The third book: the assassination of Saeta and his servants.

The fourth book: an important series of original documents reproduced verbatim on the optimistic outlook for the future of the region despite the violent death of Saeta, and fifteen other biographical sketches of earlier missionaries who met a like fate at the hands of the natives without the necessity of abandoning the missions. The sixteenth biographical sketch is that of Saeta.

The fifth book: the military efforts to pacify the rebellious Indians; the effective cooperation of the friendly natives; and also a tragic mistake with disastrous consequences. The sixth book: the present prosperous state of the missions in Pimería Alta; the historical background; Kino’s arrival in the area, his work, and his success. Special emphasis is given to the objections urged by some against the continuance of the missions in the area.

The seven book: this last part of the biography is unique in the history of Mexico. It is a presentation of the missionary methods employed by Saeta and still more by Kino, a penetrating analysis of the mental and emotional world of the Pima Indians, and their reactions to the teachings and demands of Christianity.

A brief word about each of these topics. .....

Book three is more than a mere recital of the assassination of Saeta; it is a penetrating analysis of the causes that brought it about, with practical suggestions for remedying the situation and preventing a repetition in the future. Kino rejects the false accusation that all the Pimas are involved. He proves from numerous sources that the main motive was the injustice and cruelty inflicted on the Indians of San Pedro del Tubutama, particularly the inhuman treatment inflicted by the Opata overseers. The Pimas were unjustly accused of theft, with consequent vexations, cruelty, and death caused among them by invading Spanish troops; further, the Indians of San Antonio de Oquitoa joined in the attack on Caborca because they felt deceived and insulted by the numerous false promises made to them, particularly that missionaries would be sent to them. Saeta’s own charges — children ("hijos"), Kino calls them — were not guilty of their missionary’s death, nor were they involved in the rebellion, but rather victims of it. .....

Book five is a clear account of the campaigns to pacify the rebellious natives and to punish the guilty. He devotes a chapter to the cooperation of the friendly Indians. Kino manfully relates the tragic mistakes of some of the Spaniards and of their Indian allies resulting in the massacre of innocent natives and the consequent attacks on other missions. This frankness may account for the fact that the Saeta biography did not find its way into print during Kino’s lifetime. ....

Kino now comes to the last and by far the most valuable book [book seven] for the student of the history of Mexico and the American Southwest, inasmuch as it furnishes him with the key to Kino’s method of winning over the natives, of his being able to travel among them even unescorted when he so chose, of securing their cooperation in evangelizing the areas far beyond the limits of his own mission, of securing their confidence, allegiance, loyalty, trust, and devotion to a degree unparalleled in the mission annals of Mexico. Let us take a closer look at the book.

Kino packs a world of information and advice into its few pages: the principles which should inspire the missionary in his work, the principles to be kept in mind and followed in order to preserve and augment the missions, the abilities and qualities required of a successful missionary, the objections brought against this apostolate, and the best means to carry on an effective and successful apostolate.

The author attributed to Saeta the principles and advice contained in the last book. Kino, however, also made them his own; further, a considerable portion of them presupposes a longer experience with the Indians than Saeta could have acquired in the few months he spent among them.

After listing and discussing the three key principles which should inspire the missionary in his arduous task — a sincere affection for the natives, a boundless generosity towards them, and a truly heroic endurance of the inevitable hardships — he stressed the importance of personal dedication to his work. It will not suffice to merely direct others to attend to the various tasks — instruction of the natives, visiting and consoling the sick, building churches, and so on. The Indians must see that the missionary is personally interested in them and that he will spend himself for their welfare, both eternal and temporal. And, although the divine assistance is more important than human effort, the former will not be forthcoming unless man does his part.

In discussing the principles to be kept in mind and followed in order to preserve and augment the missions, the two men agreed that the centers for the conversion of the natives and the teaching of the faith to them were to do without military assistance, as far as possible, and they were to rely solely on peaceful means. .....

Kino's Fight for Justice & Peace Continues After Return

Kino remained in Mexico City until February 8, 1696. Father Antonio de Benavides, whose immediate destination was Durango, accompanied him part of the way. Kino stopped in Conicari, where he had been eight years earlier, in order to lend a helping hand with Holy Week services. After Easter Sunday, April 22, he continued on to Santa María de Bazeraca, where he discussed the more urgent mission problems with the newly appointed visitor general, Horacio Políce. Because of the insecurity of the highways, Kino was ordered to travel in the company of Captain Cristobal de Leon, Jr., and his men. Kino had a very narrow escape: while he left the contingent to pay a visit to Father Francisco Carranco, superior at Nacori, and Father Pedro del Marmol, pastor of Huásabas, the marauding Jocomes fell upon the party he had just left, slaying the captain and all his men near the mission of Oputo. .....

In the middle of May, 1696, Kino returned to Dolores after an absence of half a year spent on his trip to Mexico City. He had sent a messenger to all parts of Pimería telling the people that Kino was returning. Native officials of every rank accepted the invitation to come to Dolores in June. What a colorful gathering this must have been! Kino greeted new and old friends with a cordiality all his own; he spoke to them in Piman, conversing with each and I addressing them in full assembly. The native officials had come in large numbers from many northern areas, walking fifty, a hundred and more leagues to reach Dolores. They came pleading for baptism and resident missionaries in their settlements. Kino could now reassure them of the promises he had received from his superiors and government officials.

Religious instruction took up much of the time, leading to the solemn ceremonies of baptism of those judged adequately prepared for its reception, but the missionary did not lose the opportunity to propose a plan of mutual defense and security against the ever-alert Apaches, nor did he forget to insist on means to improve the lot of the common people. The Pimas showed their gratitude in a very practical way by helping Kino and his servants harvest the wheat at Dolores.

Just when prospects seemed brightest for the future of Pimería Alta, widespread rumors and opposition blocked all progress. Reports and rumors got abroad that the Pimas were in revolt, that they had joined the enemy Indians in raiding, stealing, and killing; that they had slain Kino and others. The immediate result of such calumnies was to hold back the promised missionaries, mistrust the Pimas, and even punish them.

Kino fought back with all the strength he could muster.

He personally investigated and refuted every accusation. He wrote reports to defend the truth; he secured witnesses to support his cause. Fortunately, his efforts in defense of the Pimas were seconded by the new visitor general, Father Horacio Políce. The next series of expeditions reflect these valiant endeavors in behalf of his beloved Pimas. .....

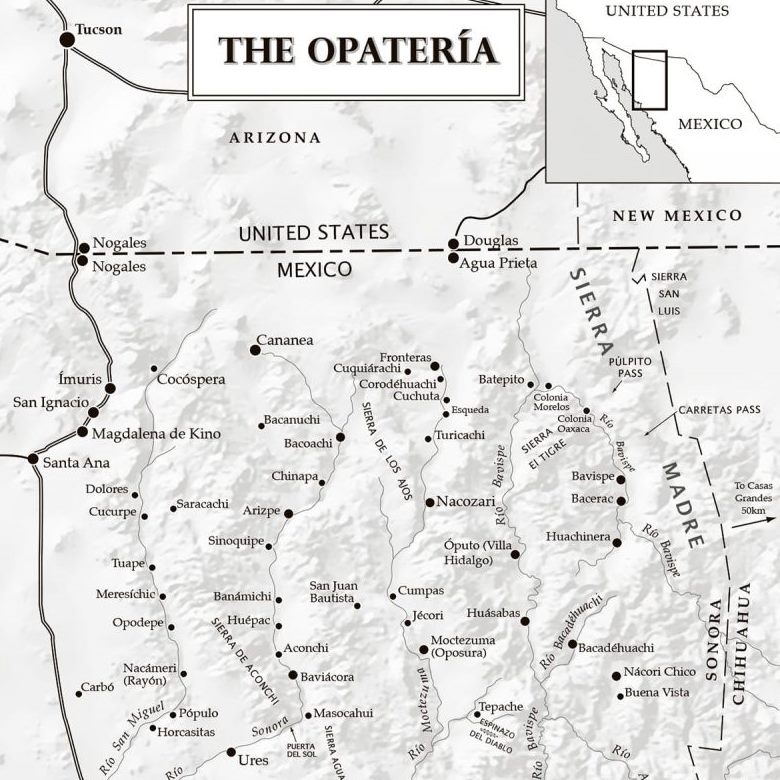

So great was the pressure of the Pima chiefs on Kino to secure missionaries for their villages that, when many of them gathered at Dolores in September of 1697, coming from fifty to a hundred and more leagues, he decided to accompany them to Santa María de Bazeraca, where Políce resided. Santa María was across the mountains close to the Chihuahua border, more than a hundred leagues (250 miles) from Dolores.

The travelers followed a trail familiar to Kino from his first trip to Dolores in 1687: via the Real de San Juan, the capital of Sonora, then Oposura (modern Moctezuma) and Guasabas (modern Huásabas). Everywhere the lay people and the missionaries gave them a cordial reception ("agasajo").

On Sunday, feast of Nuestra Señora del Rosario, October 6, the party reached Bazeraca. Políce received them with every expression of kindness and affection. Kino noted in his diary that “the next day Father Políce sang a solemn high Mass in honor of the three holy kings, the first gentiles who came to adore the Messiah.”

After making a thorough investigation of the accusations against the Pimas, Políce was convinced of their innocence and wrote a letter in their defense to the military commander. He also promised that additional missionaries for Pimería Alta would soon arrive and requested more soldiers to defend the missions and their peaceful natives. With these reassurances Kino and his Pima friends rode back to Dolores.

Above accounts from:

Chapter 6 - The Remaining Explorations in 1694

Chapter 7 - Decisive Years for Pimería Alta: 1695-1696

Chapter 8 - Discovering New Lands and Peoples: 1696-1697

Excerpts from: "Kino and Manje: Explorers of Sonora and Arizona" 1971

By Edward J. Burrus

To view entire chapters, click

Kino's Ride for Justice and Peace

The book includes an appendix of thirty documents translated by Ernest J. Burrus and map and place finder by Ronald L. Ives.

Tepeyac Hill and Mexico City

From El Valle de México Visto desde El Cerro de Santa Isabel 1875

José María Velasco

In The Capital Once More

Herbert E. Bolton

His book finished, Kino started for Mexico posthaste, to request more missionaries for his Pima Land and to report the abuses which hindered his work. His long ride to the capital and his fervent appeal to the authorities constitute the next chapter in the story. The decision to make the journey was no sudden event. Soon after he and Manje in February 1694 caught sight of California from the mountain of El Nazareno, Kino had written to the provincial asking permission to go to the capital to discuss the extension of missions into the explored mainlands, and the renewal of efforts in California. The permission was granted, but his going at this time was prevented by the protests of soldiers, officials, citizens, and missionaries, who reported to Mexico that Kino was needed in the Pimería, where he was "accomplishing more than a well-governed presidio." The Pima uprising of 1695, lasting [329] from April to the end of August, together with Kino's illness, still further delayed his going.

Now there were added reasons for the journey. It was rumored that Solis had made pernicious reports to Mexico regarding the Pimas. Complaints had been made of Kino's own methods, and he wished to answer them face to face with the authorities. And he had business with Salvatierra. So, when the peace agreements of August 30 relieved the pressure of home affairs, he decided to avail himself of the license, "almost an order, ... from the father provincial, and go to Mexico for the good of so many souls in need." As a preparation he wrote his book on the martyrdom of Father Saeta. To care for Dolores in his absence, Campos was called from San Ignacio.

"And so," he says, "setting out from these missions of Sonora on the sixteenth of November, 1695, in seven weeks, and after a journey of five hundred leagues, I arrived in Mexico on January 8, 1696." He had retraced his northward route traveled eight years before, when first he came to Pima Land. A fifteen-hundred-mile horseback ride was no small undertaking. |1| He adds, "It was God's will that I should be able to say Mass every day of this journey; and the three masses of the Feast of the Nativity I said in the new church of Nuestra Señora de Loreto of Guadalaxara. The same day on which I arrived at Mexico Father Juan Maria Salvatierra arrived by another route, |3| while that morning the new government was being installed, Father Juan de Palacios having entered as provincial."

Kino took with him to Mexico some Indian boys, among them the son of the captain general of the Pimería (head Indian of mission Dolores), as samples of the people for whom he went to plead. And they "received the utmost kindness and favors from the new father provincial and his predecessor, from his Excellency the Conde de Galve, and even from her Ladyship, the viceroy's wife, who were delighted at seeing new people who came from parts and lands so remote."

It was now fifteen years since Father Eusebio had first arrived in Mexico City from Europe, and nine since he had left there for Pima Land. A decade and a half on the frontier doubtless had left their [330] marks on his face and hands as well as on his outlook upon the world. Then he was ready to go with the ship, now he was steering it. He had become a man of affairs. Many of his old friends of first days had departed, some to their final reward, but a few were left to welcome him and listen to his tales of the border. Sigüenza was still in the capital, and Kino tells us that he was still nursing an imaginary grievance. Whether or not they met does not appear. In the interim Don Carlos, too, had been a pioneer, having taken part in the exploration of Pensacola Bay. He, as well as Father Eusebio, had become a royal cosmógrafo and thus found practical use for his mathematics.

While in the capital Kino showed his usual vigor, and succeeded with some of his purposes. He had long sessions with Father Palacios, the new provincial, and conferred personally with the viceroy and members of the Royal Audiencia. He made a heavy assault upon the false charges against and the grave abuses heaped upon his Pimas. As Alegre tells us, "He showed that in the recent uprising the guilty parties were some captains of the presidios who were excessively arrogant." Solis of course was one of them. "He demonstrated clearly the iniquity with which they had outraged the inhabitants of Mototicatzi," obtained a decision in their favor, "and an order that they should be restored to their lands." |A| Finally, he accomplished the primary object of his journey, for the provincial assured him that he should have five new missionaries for Pima Land. If the gossips spoke the truth, this friendly act did not prevent Palacios from ad monishing Father Eusebio to avoid irritating his colleagues. While in the capital Kino and Salvatierra jointly urged the resumption of missions in California, now ten years abandoned, but at the time they did not succeed. |4|

On February 8 Kino set out for the Pimería, accompanied for a distance by Father Antonio Benavides, who turned aside to Durango to prepare himself for work in Pima Land. |5| At Conicari Father [331] Eusebio stopped to observe Holy Week. From there he forwarded mail to Horacio Polici, including the dispatch appointing Polici visitor for the new triennium. Somewhat more slowly Kino followed, going to Bazeraca, far over the mountains near the Chihuahua border, to consult the new visitor about plans for the future. Henceforth the relations of these two Black Robes were intimate, it' not always placid.

On his way from Bazeraca to Dolores Kino had a narrow escape from death, an incident which he passes by with casual comment. The Jocomes were again on a rampage. By good luck Kino got safely through, but his escort was not so fortunate. "I had to return in the company of Captain Christóbal de León, his son, and his men, for the greater security of my person; but his Divine Majesty saved me from the great misfortune into which his Grace fell, for the hostile Jocomes killed him and all his people on the road not very far from Oputo, while I went to say goodbye to father rector Francisco Carranco and Father Pedro del Marmol." In the middle of May Kino arrived at Dolores after an absence of half a year. Father Campos now returned to San Ignacio. |5|

With Padre Eusebio on the job, the border awoke from a six month's sleep. His return was the occasion for a grand assemblage of Pima chiefs. While on his way to Bazeraca he had sent a messenger to Dolores to order the Indian officials there to go to all parts of the Pimería telling the people that Padre Eusebio was on his way home. They promptly complied, visited the villages, and invited governors, alcaldes, capitanes, fiscales, and caciques to come to welcome Kino and hear his messages from the great men in Mexico. In June, at the appointed time, the chiefs arrived at Dolores from all the country round. What happened there should be carefully noted. It appears like a simple matter of course, but it had an echo later.

Kino assembled the visitors in the church and addressed them in the Pima tongue. He told them how glad he was to be back, and delivered to them greetings from the viceroy; from Juan de Palacios, the new [332] provincial; and from Polici, the new visitor. "And these captains and governors and their families, having understood them all, unanimously gave signs of great gratitude for such friendly remembrances." As a more substantial way of showing their gratitude, the chiefs all turned in and helped Kino harvest his wheat, as they customarily did every year. For several days the sickles sang through the yellow grain in the valley below the church. While they were at Dolores some of the visitors were catechized and baptized; others who asked for baptism were denied it on the ground that they had not been sufficiently instructed. Under circumstances which will appear, this was a detail worth mentioning. As a record of this gathering and as evidence of Pima loyalty, a formal report of the assembly was sent to Mexico, including a list of all the Indians who took part in it. |6| [333]

Herbert E. Bolton

Chapter 90

"In The Capital Once More"

"Rim of Christendom:

A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino: Pacific Coast Pioneer"

Footnotes

|1| Kino had just passed his fiftieth birthday.

|2| Salvatierra at this time was serving at the novitiate of Tepótzotlan.

|3| Kino, "Favores Celestiales," Parte I, Lib. v, Cap. 1-2; Hist. Mem., I, 158-160. Astrain, P. Antonio, "Historia de la Compañía de Jesús en la Asistencia de España," Torno VI, 493-494. (Madrid, 1920).

|4| See note on Benavides in Mora Contra Kino, May 28, 1698 (loc. cit.). Alegre, followed by Astrain, says that Kino left Mexico accompanied by Father Gaspar Barillas, but Kino mentions only Benavides. Alegre is certainly in error when he says that Kino returned to Sonora by way of the Tarahumara country, for Kino gives circumstantial data regarding his return through Guadalajara and Conicari (Alegre, III, 12; Astrain, VI, 493).

|5| Kino, "Favores Celestiales," Parte I, Lib. v, Cap. 1-2; Hist. Mem., I, 158-161. See the San Ignacio Mission Register, where Campos says the Indians did not return till 1698. Father Carranco was apparently at Nácori when Kino turned aside to visit him. |6| [333]

|6| See Kino, "Favores Celestiales," Parte I, Lib. v, Cap. 2; Hist. Mem., I, 161; Mora Contra Kino, May 28, 1698. The list and report were sent in by a friend named Estrada

|A| Editor Note:In 1686 at the village of Mototicachi, 100 miles northeast of Dolores, the Spanish murder all the 50 adult males and imprison all women and children of the village as slaves as they act on unjustified rumors that village leaders were part of a conspiracy to revolt against the Spanish. Although outside his area of responsibility and ten years afterwars, Kino seeks justice and obtains an order from the Viceroy releasing the survivors from slavery and restoring them to their lands.

For the entire chapter "In The Capital Once More", click,

En la capital, una vez más

Herbert E. Bolton

En cuanto terminó su libro, Kino salió hacia México, a toda velocidad, para pedir más misioneros que fueran a la Pimería, y para informar sobre los abusos que habían entorpecido su labor. Su larga cabalgata a la capital y su ferviente alegato ante las autoridades son el tema del siguiente capítulo en esta historia. La decisión de hacer el viaje nada tuvo de precipitada. Poco después de que Kino y Manje divisaron California desde el cerro de El Nazareno, en febrero de 1694, Kino escribió al provincial pidiéndole permiso para ir a la capital a discutir la extensión de las misiones en las tierras exploradas en el continente, y la reanudación de los trabajos en California. El permiso fue concedido, pero en ese momento el padre Eusebio no pudo partir debido a las protestas de soldados, funcionarios, vecinos y misioneros que informaron a México que Kino hacía falta en la Pimería, donde lo que estaba haciendo era bastante más que sacar adelante "un presidio bien gobernado". La revuelta de los pimas, de abril a fines de agosto de 1695, más la enfermedad de Kino, demoraron aún más su partida.

Había ahora nuevas razones para su viaje. Corrieron rumores de que Solís había presentado a México informes negativos sobre los pimas. Los métodos mismos de Kino habían provocado quejas, y él quería responder ante las autoridades. Además, tenía asuntos con Salvatierra. Así pues, cuando las paces del 30 de agosto aliviaron la presión sobre los asuntos domésticos, Kino decidió valerse "de la licencia, casi orden, que yo tenía del padre provincial, y pasar a México, para el bien de tantas y tan necesitadas almas". Entre los preparativos para el viaje, escribió su libro sobre el martirio del padre Saeta. Para que se hiciera cargo de Dolores, durante la ausencia de Kino, se llamó a Campos, que estaba en San Ignacio.

"Y saliendo de estas misiones -escribe Kino- de Sonora en 16 de noviembre de 1695 años, en siete semanas, camino de quinientas leguas, llegué a México a 8 de enero de 1696 años." De regreso siguió la ruta que ocho años antes había recorrido hacia el norte la primera vez que llegó a la Pimería. Una cabalgata de más de dos [416] mil kilómetros no era una empresa pequeña. |12| El padre Eusebio añade: "Fue Dios servido que yo pudiere decir misa todos los días des te viaje, y las tres de la Pascua de Navidad las dije en la nueva iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Loreto de Guadalajara. El mismo día que llegué a México llegó, por otro camino, el padre Juan María Salvatierra |13| y por la mañana se había abierto el nuevo gobierno, habiendo entrado por provincial el padre Juan de Palacios".

Kino llevó consigo a México unos muchachos indios, entre ellos el hijo del capitán general de la Pimería (el jefe indio de la misión de Dolores), para dar a conocer la gente por la que iba a interceder. Y "recibimos todo agasajo y dádivas del padre provincial nuevo y de su antecesor y de su excelencia y del conde de Galve, y aun de la señora virreina, que se holgaron de ver gente nueva que venía de partes y tierras tan remotas".

Hacía quince años que el padre Eusebio había llegado de Europa a la Ciudad de México, y nueve que había salido de allí a la Pimería. Tres lustros en la frontera sin duda habían dejado sus marcas en el rostro de Kino, en sus manos y en su concepto del mundo. Cuando llegó le bastaba con abordar la nave; ahora él llevaba el timón. Estaba hecho un empresario. Muchos de los viejos amigos de los primeros días habían partido; algunos a su morada definitiva; algunos quedaban, sin embargo, para darle la bienvenida y escuchar sus historias sobre la frontera. Sigüenza todavía estaba en la capital, y Kino nos dice que aún cobijaba el rencor de una ofensa imaginaria. No sabemos si volvieron a encontrarse. En el ínterin también don Carlos la había hecho de pionero, pues participó en la exploración de la bahía de Pensacola. Al igual que el padre Eusebio, Sigüenza fue nombrado cosmógrafo real y así encontró una aplicación práctica para sus conocimientos matemáticos.

En la capital, Kino dio muestras de su habitual energía y alcanzó algunos de sus propósitos. Tuvo largas sesiones con el nuevo provincial, el padre Palacios, y se entrevistó personalmente con el virrey y con miembros de la Real Audiencia. Arremetió vigorosamente contra las acusaciones falsas levantadas a los pimas y los [417] graves insultos amontonados en su contra. Como nos dice Alegre, Kino demostró que en la reciente revuelta los culpables eran algunos capitanes de los presidios que eran demasiado prepotentes. Uno de ellos, naturalmente, era Solís. Kino "mostró, claramente, la iniquidad con que habían sido atropellados los habitadores de Mototicatzi", y logró una sentencia en favor suyo para que les fueran restituidas sus tierras. |14| Por último, cumplió con el propósito primordial de su viaje, pues el provincial le aseguró que tendría cinco nuevos misioneros para la Pimería. Si puede creerse en las habladurías, este acto amistoso no evitó que Palacios amonestara al padre Eusebio para que dejara de irritar a sus colegas. Mientras estaban en la capital, Kino y Salva tierra unieron sus esfuerzos para solicitar que se reanudaran los trabajos de las misiones en California, que llevaban ya diez años de abandono, pero en ese momento no tuvieron buen éxito. |15|

El 8 de febrero, Kino salió hacia la Pimería, acompañado durante algún trecho por el padre Antonio Benavides, quien se desvió hacia Durango con el propósito de prepararse para trabajar en la Pimería. |16| En Conicari, el padre Eusebio se detuvo para celebrar la Semana Mayor. Desde allí envió por delante correo para Horacio Polici; entre otras cosas, el oficio que lo nombraba visitador para el siguiente trienio. Algo más lentamente, Kino siguió hacia Bazeraca, lejos, más allá de las montañas, cerca de la frontera de Chihuahua, para consultar con el nuevo visitador acerca de sus planes para el futuro. De allí en adelante, las relaciones entre esos dos ropas negras fueron muy estrechas, aunque no siempre plácidas.

En su camino de Bazeraca a Dolores, Kino escapó por poco de la muerte; incidente que comenta apenas de paso. Los jocomes andaban de nuevo alzados. [418] Por buena suerte, Kino pasó por sus tierras sin dificultades, pero su escolta no fue tan afortunada. "Yo había de venir de vuelta en compañía del capitán Cristóbal de León y de su hijo y de su gente, para mayor seguridad de mi persona, pero su divina Majestad me escapó de la gran desgracia en que cayó su merced, matándole los enemigos joco mes a él y a toda su gente en el camino, no muy lejos de Oputo, mientras yo fui a despedirme del padre rector Francisco Carranco y del padre Pedro del Mármol." Kino llegó a Dolores a mediados de mayo, tras una ausencia de medio año. El padre Campos regresó a San Ignacio. |17|

Con el padre Eusebio de regreso en su lugar, la frontera despertó de seis meses de letargo. Su retorno fue la ocasión para una gran asamblea de jefes pimas. Cuando iba camino a Bazeraca, mandó un mensajero a Dolores para pedir a los caciques indios que estaban allí que fueran por todos los rincones de la Pimería y le dijeran a la gente que el padre Eusebio venía camino a casa. Los jefes cumplieron prontamente con su cometido, visitaron las rancherías e invitaron a los gobernadores, alcaldes, capitanes, fiscales y caciques a que fueran a recibir a Kino y a escuchar los mensajes que traía de los grandes hombres de México. En junio, en el tiempo previsto, los jefes llegaron a Dolores de todos los alrededores. Hay que tomar en cuenta cuidadosamente lo que sucedió allí. Parece ser algo apenas rutinario, pero más tarde levantó ecos.

Kino reunió a los visitantes en el templo y se dirigió a ellos en pima. Les dijo lo contento que estaba de hallarse de vuelta y les dio los saludos que les enviaban el virrey, el nuevo provincial Juan de Palacios, y el nuevo visitador Horacio Polici. "y todos recibieron los muy paternales y muy católicos recaudas de los padres provinciales y de sus excelencias, con varias dádivas que entre tanto se les enviaban. Y los despaché consolados." Como una manera más sustancial de mostrar su gratitud, todos los jefes regresaron y ayudaron a Kino a levantar la cosecha de trigo, como solían hacerlo cada año. Durante varios días las hoces cantaron sobre las espigas doradas en los trigales al derredor de la iglesia. Mientras estaban en Dolores, algunos [419] de los visitantes fueron catequizados y bautizados; a otros se les negó el bautismo que pedían porque se consideró que no tenían instrucción suficiente. Bajo circunstancias de las que pronto hablaremos, éste fue un detalle que vale la pena mencionar. Como una memoria de esta reunión y como una prueba de la lealtad de los pimas, se envió a México un informe formal sobre la asamblea, que incluía una lista de todos los indígenas que estuvieron presentes en ella. |18| [420]

Herbert E. Bolton

Capitulo 90

"En la capital, una vez más"

"Los confines de la cristiandad:

Una biografía de Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J., isionero y explorador de Baja California y la Pimería Alta"

Notas

|12| Kino acababa de cumplir cincuenta años.

|13| En ese tiempo Salvatierra se hallaba en el noviciado de Tepotzotlán.

|14| Alegre, "Historia de la provincia de la Compañía de Jesús de Nueva España", edición de Burrus y Zubillaga, Roma, Institutum Historicum Societatis Jesu, 1960, vol. IV, p. 123.

|15| Kino, "FC", ["Favores Celestiales"] I, v, 1-2; Bolton, "KHM", ["Kino's Historical Memoir"] I, 158-160; Astrain, "Historia de la Compañía de Jesús en la asistencia de España", Madrid, 1920, tomo VI, pp. 493-494.

|16| Véase la nota sobre Benavides en Mora contra Kino, 28 de mayo de 1698, loco cit. Alegre, y Astrain lo sigue, dice que Kino salió de México acompañado por el padre Gaspar Barillas, pero Kino menciona sólo a Benavides. Ciertamente Alegre está equivocado cuando dice que Kino regresó a Sonora por tierra de los tarahumaras, pues Kino describe detalladamente su camino de regreso por Guadalajara y Conicari. Alegre, vol. III, p. 12; Astrain, tomo VI, p. 493; Burrus y Zubillaga, vol. IV, p. 123, n. 25.

|17| Kino, "FC", I, v, 1-2. Véase el registro de la misión de San Ignacio, donde Campos dice que los indios no regresaron hasta 1698. Al parecer, el padre Carranco se encontraba en Nácori cuando Kino se desvió para visitarlo.

|18| Véase Kino, "FC", I, v, 2; Bolton, "KHM", I, 161. Mora contra Kino, 28 de mayo de 1698. La lista y el informe fueron enviados por un amigo llamado Estrada.

Kino's Recommendations To Preserve Missions

Padre Saeta Biography

Eusebio Francisco Kino

The venerable Father Francisco Javier Saeta wanted to avoid as often as possible the entry of harsh or indiscreet soldiers into places where there is no firm government. It can and does happen that instead of calming and composing matters with the natives through the imposition of a firm, prudent, and Christian punishment, these soldiers excite, scandalize, horrify, and disrupt everything. Whole tribes have been lost by punishing some indiscreetly, whether justly or unjustly, and by inflicting severities upon them. The rest of the natives flee or hide out of sheer fear. There will certainly be uprisings and there will be worrisome, even sinister, rumors of rebellion and apostasy of whole nations. These are things which the most sensible and experienced captains and generals realize have happened and will happen.

I. If it should happen that, instead of punishing the guilty who are wont to hide, defend, and look out for their own endangered and misguided lives, some soldiers seize the first Indians they chance upon, who because of their innocence do not resist or even carry weapons, those poor souls will be made to pay for the offenses of the guilty. The soldiers merely employ this practice on the grounds that it is too much work and too risky to punish evildoers. There is no doubt that in such a case the presidio, instead of gaining, will lose; instead |191| of settling affairs, it will leave everything more agitated and confused; and instead of remedying the matter, it will change it radically for the worse. And, as always, this will lead to newer, prolonged expenses for even more tedious tasks affecting the very same soldiers themselves.

II. Another enormous obstacle would result if the soldiers, under the pretext of making peace, would trick the natives by inviting them to a council without weapons and under the sign of the Cross, and, then, cruelly slaughter them.

III. It would also be a great blunder if, out of pure greed, these soldiers did not want to return from their expedition without taking some slaves, and not having been able to capture any enemy Indians, they should apprehend and carry off some innocent natives. ...

In this way the royal, Catholic forces unanimously will procure the just punishment of only the guilty and the protection of the good, so that not only will they not abandon the apostolate of these new conquests and conversions, which |193| it seems that some persons have feared (according to the reference Father Andrés Pérez de Ribas makes in his History), but these Christian forces will receive the special renown from these new missions of being called apostolic presidios.

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Book Eight Chapter Two

Biography of Padre Saeta 1695

El Valle de México Visto desde El Cerro de Santa Isabel 1875

Painting Detail Showing Road From epeyac Hill to Mexico City

José María Velasco

"My Journey to Mexico And My Return To The Missions"

Eusebio Francisco Kino

Book V

My Journey to Mexico And My Return To The Missions; Visitation Of The Father Visitor, Oracio Police; Various Entries To The North, The West, And The Northwest; Discovery And Reduction Of New Nations

Chapter I

My Journey To Mexico To Obtain Missionary Fathers For This Pimeria |158|

Since the year before, and earlier, when from these coasts of this Pimeria we caught sight of California nearby, I had asked and obtained permission from the father provincial, Diego de Almonacir, to go to Mexico to discuss with his Reverence and with his Excellency the conversion of California and the extensive new lands of this mainland; but my going had been prevented by the royal justice and some fathers, the lieutenants, and citizens of this province, who reported to Mexico that I should be needed here, and that I was accomplishing more than a well governed presidio, etc. This year, 1695, however, in view of the very Christian truces which had been drawn up on the thirtieth of August in this Pimeria, and since the harvest of souls [158] was so plenteous, so widespread, and so ripe, I determined, although some opposed me, to avail myself of the license, almost an order, which I had from the father provincial, and to go to Mexico for the good of so many souls in sore need; and so, setting out from these missions of Sonora on the sixteenth of November, 1695, |159| in seven weeks and after a journey of five hundred leagues, I arrived at Mexico on January 8, 1696.

It was God's will that I should be able to say mass every day of this trip; and the three masses of the Feast of the Nativity I said in the new church of Nuestra Señora de Loreto of Guadalaxara. The same day on which I arrived at Mexico Father Juan María Salvatierra |160| arrived by another route, while that morning the new government had been installed, Father Juan de Palacios having entered as provincial. I took with me to Mexico the son of the captain general of this Pimeria, and we received the utmost kindness and favors from the new father provincial and his predecessor, from his Excellency the Conde de Galves, and even from her Ladyship, the viceroy's wife, who were delighted at seeing new people who came from parts and lands so remote.

In reference to California, on account of various mishaps, neither I nor Father Juan María Salvatierra accomplished our purpose at that time, although the year following Father Juan María did accomplish it at the coming of the new viceroy, Conde de Valladares, etc. In regard to fathers for this Pimeria, I obtained five from the new father provincial, Juan de Palacios, through reports, false or ignorant, and the contrary opinions of those less interested, delayed everything, or almost everything, as usual.

Chapter II

My Departure From Mexico And Arrival At These Missions Of The Pimeria

February 8, 1696. On the eighth of February, |161| 1696, I set out from Mexico with Father Anttonio de Benabides, |162| who came to prepare himself in Guadiana |163| for this Pimeria. I came to observe Holy Week and Easter at Conicari, whence I forwarded the despatch of the government and many other letters which I was carrying to the new father visitor, Oracio Polise, and to other fathers. Afterward I passed on to Santa María de Bazaraca |164| to see the father visitor; and I found in his Reverence all affection and a very great and fatherly love for these new conversions. I had to return in the company of Captain Christóbal de León, his son, and his men, for the greater security of my person; but his Divine Majesty saved me from the [160] great misfortune into which his Grace fell, for the hostile Jocomes killed him 165 and all his people on the road not very far from Oputo, 166 while I went to say goodbye to the father rector, Francisco Carranco, and Father Pedro del Marmol. |167| In the middle of May I arrived at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores. While I was gone to Mexico Father Agustin de Campos had administered the mission; |168| and his Reverence upon my return went to his mission of San Ygnacio.

In June, as the Pima children of the interior had heard of my return from Mexico, their principal governors and captains came to see me in such numbers and from parts so remote, from the north, from the west, etc., that Captain Don Antonio de Estrada Bocanegra, |165| who had been an eye-witness, wrote a long account of them, noting the fifty, sixty, seventy, eighty, ninety, and one hundred or more leagues' journey which many of them had come, all for the purpose of asking and obtaining holy baptism and fathers for their rancherias and for their many people. All received the very paternal and very Catholic messages of the father provincials and of their Excellencies, with various gifts which meanwhile they had sent them; and I sent them away comforted with fair hopes that by the divine [161]Grace they should accomplish the good intent and purpose which they professed of obtaining missionary fathers.

Chapter III

New And Old And Very Violent Contradictions And Opposition Which Hindered The Coming Of The Missionary Fathers To This Pimeria |170|

Nevertheless, so great were the obstacles and the opposition against this Pimeria that they caused even the most friendly father visitor, Oracio Polise, to falter. It was again reported, but very falsely, as has since been seen, that the Pimas Sobaipuris were closely [162]allied with the hostile Jocomes, and with the other enemies of this province of Sonora; and they were charged with stealing droves of horses, etc., and with having many large corrals full of them. It was falsely reported, also, that these Pimas were involved in the tumults and revolts of Taraumara, on the testimony of the Taraumares themselves, but the Taraumares could not have been speaking of the Pimas of this Pimeria, who are more than one hundred and fifty leagues distant from the Taraumares, but only of the Pimas near them, who are those of Tapipa and near Yecora. |171| It had been said and reported, but very falsely, that the Pimas of the interior and their neighbors were such cannibals that they roasted and ate people, and that for this reason one could not go to them; but already we have entered and have found them very friendly and entirely free from such barbarities.

I found it published at the coming of his Illustriousness to Matape that Father Kino was asking in letters that they bring him with soldiers out of the tumultuous Pimeria, when such a thing had never entered my thoughts. |172|

It was said and written to Mexico that I lived guarded by soldiers, but I have never had, nor thanks to the Lord, needed such a guard. It has been said and written that the Sobaipuris and others farther on had killed Father Kino and all his people who went with him in the entry of 1698 ; but the fact is that in all parts they received us with the utmost kindness and, thanks be to the Lord, we are still living. |163|

Toward the end of July of the past year it was reported that the Soba nation was in commotion, and that we three |173| fathers were in great danger of our lives. Father Barillas was taken from La Consepcion, |174| and the garrison was summoned and came. But there was not then nor is there now the least of these pretended dangers.

Another great contradiction and opposition and very false report has been that the Pimeria has few people and does not need many fathers. But it is a very well established fact that it has more than fifteen thousand souls.

Chapter IV

Various Entries To The Northeast |175| And To The North By Order Of The Father Visitor, Oracio Polise; And The Delivery Of The District Of Cocóspera To Father Pedro Ruis De Contreras

Nevertheless, in order that conditions might be investigated and the facts ascertained, the father visitor, Oracio Police, bade me make various entries, in which talks and instruction in Christian doctrine and in life somewhat civilized were given; and the very submissive natives gave me many little ones to baptize.

On the tenth of December I went to San Pablo de Quiburi, a journey of fifty leagues to the north, passing by Santa María and by Santa Cruz, of the Rio de San Joseph de Terrenate. I arrived at Quiburi on the fifteenth of December, bearing the paternal greetings which the father visitor sent to this principal and great [164] rancheria; for it has more than four hundred souls assembled together, and a fortification, or earthen enclosure, since it is on the frontier of the hostile Hocomes. As a result of the Christian teaching, the principal captain, called El Coro, gave me his little son to baptize, and he was named Oracio Polise; and the governor called El Bajon, |175a| and others, gave me their little ones to christen. We began a little house of adobe for the father, within the fortification, and immediately afterward I put in a few cattle and a small drove of mares for the beginning of a little ranch.

On the thirteenth of January, 1697, I went in to the Sobaipuris of San Xavier del Bac. We took cattle, sheep, goats, and a small drove of mares. The ranch of San Luis del Bacoancos was begun with cattle. Also there were sheep and goats in San Cayetano, which the loyal children of the venerable Father Francisco Xavier Saeta had taken thither, having gathered them in Consepcion at the time of the disturbances of 1695. At the same time, some cattle were placed in San Xavier del Bac, where I was received with all love by the many inhabitants of the great rancheria, and by many other principal men, who had gathered from various parts adjacent. The word of God was spoken to them, there were baptisms of little ones, and beginnings of good sowings and harvests of wheat for the father minister whom they asked for and hoped to receive.

On the seventeenth of March, 1697, I again went in to San Pablo de Quiburi. |176| I returned by way of San [165] Geronimo, San Cayetano, and San Luys, looking in all places after the spiritual welfare of the natives, baptising some infants and sick persons, and consoling all with the very fatherly messages from the father visitor, and even from the Senor alcalde mayor and military commander, notifying them at the same time to be ready to go with the soldiers on the expedition against the enemies of the province, |177| the Hocomes, the Xanos, Sumas, and Apaches. With the same intent and purpose I again went in to San Pablo de Quiburi on the seventeenth of April, and they received me with crosses and arches placed in the road.

At this time I gave over the district of Cocóspera |178| and Santa María to Father Pedro Ruis de Contreras, with complete vestments or supplies for saying mass, good beginnings of a church and a house, partly furnished, five hundred head of cattle, almost as many sheep and goats, two droves of mares, a drove of horses, oxen, crops, etc. |179|

Chapter V

The Principal Captains And Governors Of This Pimeria Go To Santa María De Bazeraca To See The Father Visitor And Ask For Fathers, A Journey Of More Than One Hundred And Then Of More Than One Hundred And Fifty Leagues |180|

So great were the desires of the natives of this Pimeria to obtain missionary fathers that they determined [166] to go to Santa María de Baceraca |181| to ask them of the father visitor. Some had come the fifty, sixty, eighty, ninety, one hundred, and more leagues' journey to reach Nuestra Señora de los Dolores; |182| and as there was still a journey of about one hundred leagues to Santa María de Bazeraca, and as they had never gone so many leagues away from their country, I went with them through Sonora. In the Real de San Juan, in Oposura, and in Guasavas, through which we passed, both the seculars and the fathers received us with all kindness. On the sixth of October, day of Our Lady of the Rosary, we reached Santa María de Baceraca.

We were received with a thousand tendernesses and with such joy by the father visitor, Oracio Police, that his Reverence on the following day chanted a solemn mass to the three holy kings, who were the first gentiles who came to adore the Messiah -" Primitiae Gentium." |183| And his Reverence, through various inquiries, even secret, which he made and ordered made, was so well satisfied with the great loyalty of these Pimas that he wrote a very fine letter to the Senor military commander requesting that the Pimeria should be favored; that efforts should be made to secure for it the fathers which it needed and deserved, since thereby the province would be quieted and made rid of the hostile Jocomes and Xanos, who would retreat to the east (all of which was [167] afterward fulfilled to the letter) ; and that some soldiers should come into this Pimeria, at least as far as Quiburi, to see with their own eyes the good state of affairs and the ripeness of the very plentiful harvest of souls. |184| Having asked when the soldiers were coming to Quburi, I was told the 7th of November. And the same day I entered also from Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, with Captain Juan Matheo Manje. |185| Our intention was to penetrate forty or fifty leagues further inland, down the Rio de Quiburi, to the last Sobaipuris of the northeast and to the Rio de Jila, or Rio Grande, which is the same, for up to that time we had not penetrated so far inland by that route. [168]

Eusebio Franciso Kino

"Favores Celestiales"

In "Kino's Historical Memoir of the Pimeria Alta" 1919

Translator and Editor: Herbert E. Bolton

Footnotes

|158| For an account of this trip to Mexico, see Bancroft, "North Mexican States and Texas", vol. i, 262-263 ; Alegre, "Historia," vol. iii, 88-89 1 "Apostólicos Afanes", 263; Manje, "Luz de Tierra Incógnita", libro ii, cap. iv (45). The account given by Alegre is in some respects better than that given here by Kino especially with respect to the details of Kino's efforts while in Mexico to secure justice for the Pimas. He says nothing, however, of Kino's efforts in behalf of California during this journey. In fact, none of the other authorities except the "Afanes" mention them.

|159| The details given here with respect to the date of leaving for Mexico, and the taking of the chief's son with him, are lacking in the other authorities except the "Afanes".

|160| Alegre says that Salvatierra, Zappa, and Kino all three arrived on the same day {op. cit., p. 89). The "Afanes" gives January 6 as the day of Kino's arrival in Mexico. [159] from the new father provincial, Juan de Palacios, though afterward the reports, false or ignorant, and the contrary opinions of those less interested, delayed everything, or almost everything, as usual.

|161| This detail is lacking from the other accounts except the "Afanes".

|162| Alegre ("Historia," vol. iii, 89) says that Kino brought with him Father Gaspar Barrillas. If this be true, it is strange that Kino does not mention the fact. Could Kino mean Barrillas instead of Benavides? According to Manje, upon the arrival of Barrillas, he was conducted to Tubutama and Caborca, in the latter of which places he reestablished the destroyed mission (op. cit., 46). Ortega states that Kino conducted Barrillas to Caborca in February, 1697 (cited in Bancroft, "North Mexican States", vol. i, 263). Kino shows that it was in 1698, after the expedition with Bernal {post, page 175). It may be, therefore, that Barrillas did not return with Kino, who reached Dolores in May, 1696. Ortega implies that none of the five missionaries were sent ("Apostólicos Afanes", 264).

|163| Guadiana is the same as Durango, where there was at this time a Jesuit college. It was long the capital of Nueva Vizcaya, and is now the seat of government of the state of Durango.

|164| Santa María Bazeraca (now Bacerac) is situated on the north flowing stretch of the upper Yaqui River, nearly straight east of Arizpe, near the Chihuahua boundary, and high in the mountains. See "Map" and "Index."

|165| for the details of this massacre see Manje, "Luz de Tierra Incógnita", libro ii, 45-48 and page 162, footnote. The references cited give the geography of the event. Alegre gives the Apaches as the aggressors.

|166| Oputo [now Moctezuma] is on the upper Yaqui River, just north of latitude 30 , and southeast of Arizpe.

|167| These details are omitted from the other accounts.

|168| That is, he reestablished his mission, which had been destroyed in 1695. (See Manje, "Luz de Tierra Incógnita", libro ii, 46, on this point). After the Pima revolt had been quieted in 1695, Father Campos served as chaplain in a campaign against the Jocomes and Janos. During this campaign General Therán de los Ríos lost his life (Manje, "Luz de Tierra Incógnita", libro ii, 45).

|169| This item is lacking from the other accounts.

|170| In September, 1695, the three companies which had been in the Pimeria, with Father Campos as their chaplain, made a campaign against the Jocomes and Janos, who were pestering Sonora. In this campaign they killed sixty and captured seventy of the enemy, the captives being distributed as slaves among the soldiers. In the course of the expedition most of the soldiers were taken ill, from drinking poisoned water, as it was believed, and General Therán de los Ríos died. In January, 1696, Captain Antonio de Solis punished the Conchos, and put to death three leaders at Nácori, south of Oputo, in the upper Yaqui Valley, Father Carranco being present at the execution. In March the Apaches, Jocomes, and Janos, who had attacked Tonibavi, were punished, eighteen being killed. Sometime before May (for Kino was with the party) the same Indians attacked the party of Captain Cristóbal de León, in the Sierra of San Cristóbal, while they were on their way from Cusiguriachi. Father Kino, who had been in De León's band, fortunately had just turned aside to visit Fathers Carranco and Marmol, as related on page 161. To avenge this attack the Compañia Volante went to the Sierra de Batepito, near Corodeguachi, but had little success. Jironza now called on the chiefs of the Janos and the Pimas to make a general campaign. They united at the Sierra Florida, near the Gila, and succeeded in killing thirty-two men and capturing fifty women and children. During the same year of 1696 a general uprising was attempted in Tarahumara, Tecupeto, and Sonora, under the influence of chief Quigue, or Quihue, of the pueblo of Santa María Baseraca. After ten leaders had been hanged at San Juan Bautista and Tecupeto, and chief Quigue had lost his life near Janos, quiet was restored. For the rebel chief's eloquent speech setting forth the grievances against the Spaniards, see Alegre, op. cit.

|171| Yecora is on an upper branch of the Yaqui River in western Chihuahua.

|172| Alegre alludes to these charges in his "Historia," vol. iii, 101. The events to which he refers took place in 1697.

|173| That is, Kino, Campos, and Barrillas.

|174| This statement is an implied contradiction of Manje's assertion that Caborca was occupied only at times ("Luz de Tierra Incógnita", libro ii, 46).

|175| This chapter is very important as giving the actual details of the preparations which Kino made for the missionaries in the San Pedro and Santa Cruz valleys. Except for Ortega's summary of it, these circumstances have not hitherto been clear. (Bancroft accepts Ortega at this point). No other authority states the number of trips made to these places by Kino in 1696 and 1697. See Bancroft, North Mexican States, vol. i, 263.

|175a| "El Coro" means "The Chorus"; "El Bajon" means "The Bassoon."

|176| Alegre by error puts in at this point the account of the Pima victory over the Apaches which occurred on March 30, 1698. He not only puts it under the date of 1697, but before the visit of the Pimas to Father Polici, related in the next chapter as occurring in October, 1697, and before the expedition of Bernal to the Gila, which was in part a result of the visit of Polici (Alegre, "Historia", vol. iii, 100).

|177| This statement illustrates the part which virile missionaries like Kino played in the defence of the frontier.

|178| Notice that Kino's language implies that Cocóspera was the principal place and Santa María the subordinate. Bancroft states that early in 1697 Father Ruiz arrived and was put in Suamca, with Cocóspera as a "visita."

|179| For references to events of this period see in volume ii, page 157, a letter to Kino by Father General Thirso Gonzaléz, dated December 27, 1698, in reply to one from Kino dated June 3, 1697. It is far out of place, and should be read in this connection.

|180| For another account of some of the events of this chapter, see Alegre, "Historia," vol. iii, 101. He supplies a few details not given here.

|181| On the upper Yaqui River. See ante, footnote 164.

|182| Alegre states that they arrived at Dolores toward the end of September. This may be merely an inference from the foregoing, but it is evident that he had access to documents at this point which I have not seen. He states that chief Pacheco had brought his wife to Bacanutzi (Bacanuchi), thence to Dolores, thence to Toape, where she was baptized as Nicolasa, and that the coming in September was a second visit for the purpose ("Historia", vol. iii, 101).

|183| "The first fruits of the Gentiles" (2 "Thess.", ii, 12. "Quod elegerit vos Deus primitias in salutem": "God hath chosen you first fruits unto Salvation")

|184| Credit for suggesting an expedition by soldiers to the interior Pimas is here given to Father Polici. Manje takes the credit to himself. See "Luz de Tierra Incógnita, libro ii, cap. 5, first paragraph: "y por estinguir yo el mal Concepto, con q nos abrasavan la venida de Evangelicos operarios pa. su Redución con Cautela suplique al Genl. mi tio entrase una escuadra de soldados en conpa. del Pr. Kino y mia, a esta descubrimiento" (p. 49).

|185| Kino and Manje left Dolores on November 2, with ten Indian servants, thirty horses, and presents for the Indians. They went via Remedios, Cocóspera (where Father Pedro Ruiz de Contreras was stationed) San Lazaro, Santa Cruz de Gaybanipitea (here they were met by Bernal with the soldiers) and Quiburi where they arrived on the 9th (Manje, Luz de Tierra Incognita, libro ii, cap. 15). Bernal in his diary says that he overtook Kino at Quiburi on the ninth. Kino gives circumstantial evidence to show the same thing, but Manje says that Bernal joined them on the seventh at Santa Cruz de Gaybanipitea (Diary, Nov. 7).

Before Kino's Ride To Mexico City

Tubutama Uprising, Spanish Response & Kino's Peace

Kino Drawing of Saeta Death

Detail from Kino's Hand-drawn "Biography of Father Saeta" Map

Tubutama and Caborca - The Beginning

Saeta Biography Account

Eusebio Francisco Kino

These variations are founded either on the diversity of the individual events and motives, or from not having heard the facts or from living far away from the happenings. This was the situation of the informers who were, perhaps, badly informed — as when they reported that all the Pimeria (which has over ten thousand souls) was rising in rebellion and apostacy; actually only seven or eight rancherías or locales were the delinquents and evildoers. The rebellion hardly involved more than two or three hundred malefactors and accomplices. If, at the start, there would not have been such mistaken and disgraceful leadership, many or all of the evils, which later befell San Ignacio and San José de Imuris, would have been avoided.

I will recount here the circumstances and causes which, before God and my conscience, I have witnessed at close range. Using these clear and very particular sources of facts, I desire in Our Lord to propose necessary and useful remedies for the future in matters which are so much for the service of the two Majesties and for the common good of so many souls. I am convinced that, if evils are never manifest, they remain unknown; if they are unknown, they are irremediable; if they are irremediable, we are left always with the same burdens, misfortunes, set-backs, and miseries. We lose time and, perhaps, the glory of eternity. Such matters elicit very serious concern. ...

The fourth circumstance or cause that has contributed to these deaths, riots and outbreaks has been the constant opposition to the Pimas which in turn has been founded on sinister suspicions and false testimony as well as on rash judgments because of which many unjust killings have been perpetrated in various parts of the Pimeria.

The Pimas have been viciously and unjustly blamed for the thefts of the livestock and the plunder of the frontiers. Such was the widespread opinion particularly until last June when General Juan Fernández de la Fuente and General Domingo Terán discovered the booty among the Jocomes and Janos; it is evident that the treatment of the natives in the Pimeria has been very unjust — leading as it has to mistreatment, torture and murder ....

We must not for any reason fail to try to remedy our own errors, faults, defects, harshness or severity, and our narrowness, displays of temper, and foolish resentments. Our common sense, prudence, and Christian charity has to solve and overcome these difficulties in dealing even with these most barbaric peoples, winning them for our most Catholic King and for our eternal God. ...

From the beginning of March, 1695, and even some months before, there was in the pueblo of San Pedro del Tubutama some punishment or other involving in particular two Indian chiefs and pagan officials who had come to the pueblo from nearby rancherías. One of them died from the harsh whipping that he received. After disappointments and disorders broke out in several places at different times, the mistreatment which Antonio, the alien Opata, who was a servant at the parish, was inflicting on the natives was deeply felt. But the action he undertook on Monday of Holy Week, March 28, was especially harsh and disagreeable. On the farm of the mission he furiously beat the foreman of the vaqueros, who was still a pagan; he drove him to the ground, kicking him with spurs and lacerating him all over his body, particularly in the ribs and flanks; he left him half-dead. ....

The foreman, seeing himself in peril, told his Pima companions : "Look, my brothers; this Opata is killing me, protect me! Defend me! ”At that the other pagans wounded Antonio with two arrows. But even then he managed to mount a good horse and fled to the pueblo where he entered the house of a friend who was still unbaptized (and who is today the governor of the pueblo). His opponents followed and, advancing on him, killed him and two other Opata Indians who were by chance in the pueblo. ....

Many boasted that they would do the same or order the same to be done within two or three days at the other mission of La Concepción further away, in order to rid themselves of ill-treatment by aliens. ...