The Californias and Gulf of California

Pirates, Manila Galleon and Vision

Kino - California Explorer

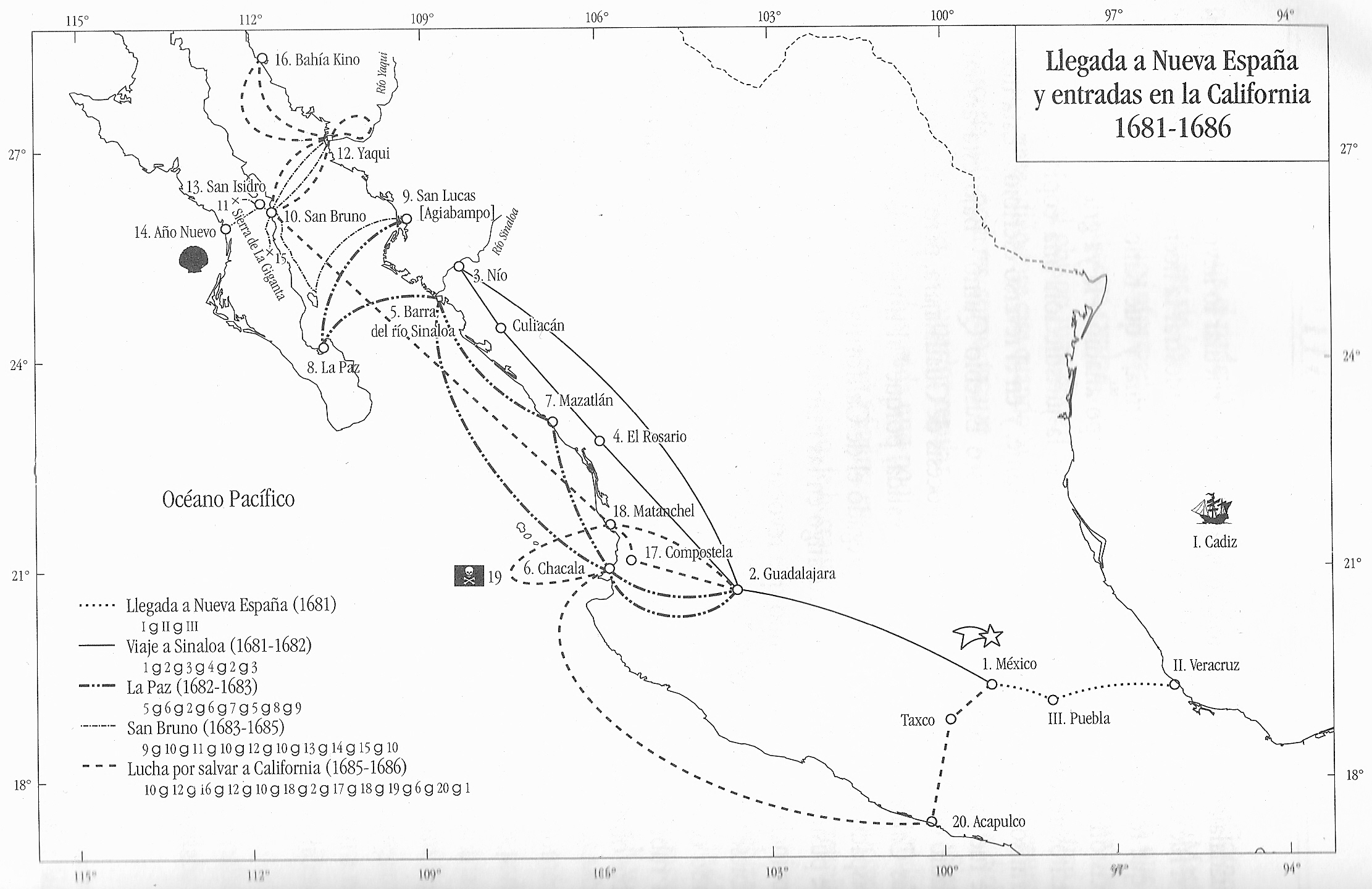

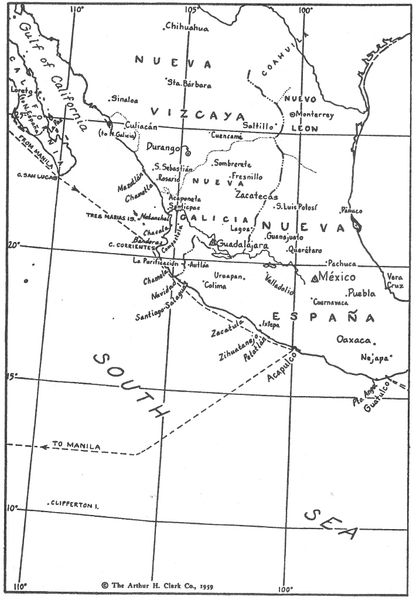

Map of Kino's Mexican Mainland, California and Pacific Ocean Trips

Before Kino's Assignment to the Pimería Alta

To View Legend, click Llegada Map Legend document (pdf)

Map Legend

mbers below route entries correspond to numbers associated with place names.

................

Llegada a Nueve Espana (1681) (Arrival to New Spain)

I * II * III Example: I (Cadiz) II (Veracruz) III (Puebla)

__________

Viaje a Sinaloa (1682 - 1682) (Journeys to Sinaloa)

1 * 2 * 3 * 2 * 3

..__..__..__.

La Paz (1682 - 1683)

5 * 6 * 2 * 6 * 7 * 5 * 8 * 9

._._._._._._.

San Bruno(1683 - 1685) (includes 1st exploration across Baja)

9 * 10 * 11* 10 * 12 * 10 * 13 * 14 * 15 * 10

- - - - - - - - -

Lucha por salvar a California (1685 - 1686) (Fight to Save the Californias)

10 * 12 * 16 * 12 * 10 * 18 * 2 * 17 * 18 * 19 * 6 * 20 * 1

Editor Note: Map from "Los Confines de la Cristiandad" (2001) which is a translation by Felipe Garrido Spanish translation of Herbert E. Bolton's "Rim of Christendom." (page 158) New map compiled by Dr. Gabriel Gomez-Padilla, one of the world's greatest Kino scholars.

Largest Monumental Kino Statue

Founding Father of The Californias

Tijuana, Baja California

Kino and Baja California

Beginnings, Twelve Year Advocacy for Return & Sonoran Mission Support

Ronald L. Ives

Featured Main Article

La Paz - Mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe 1683

Although there were sporadic attempts to colonize Baja California from the time of Hernán Cortés (1533), none accomplished much of lasting importance until the time of the Kino-Atondo expedition of 1683-1685. This expedition, with Admiral Don Isidro Atondo y Antillón as military commander and Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. (see n. 14) as chief missionary, was organized to make a lasting settlement on the peninsula. [39] It almost succeeded. Father Kino was appointed "juez eclesiastico vicario" as representative of the Bishop of Durango whose jurisdiction was a bit uncertain, and also royal cosmographer as a representative of the king whose jurisdiction was clear. Sailing from Chacala, Sinaloa, on January 17, 1683, the expedition arrived in two <28> ships in the harbor of La Paz, Baja California on April l, several stops having been made en route.

The site chosen for the settlement was in a palm grove with a well of good water nearby; it is now occupied by the modern city of La Paz. Formal possession of the country was taken on April 5 by Admiral Atondo, acting in the name of King Carlos II. Immediately thereafter, Father Kino, assisted by his companion Father Goñi, took spiritual possession of California in the name of Bishop Juan Garbabito of Guadalajara. Formalities concluded, a church and fort were begun; fields were plowed and planted; and the "Capitana" was careened to prepare for a voyage to the Río Yaqui for more supplies. The environs of La Paz were explored during this time, and the fathers began to learn the local Indian language. Initially, the outlook for the La Paz colony seemed promising.

By June trouble with Indians began to break out. There were two local tribes, the Guaicuras and Coras, who were not on the best of terms. In attempting to deal equally with both, the missionaries gained the confidence of neither. The soldiers, likewise, had their difficulties. Although willing to accept presents, the Guaicuras tended to be belligerent and intractable and were not overly impressed by the lethality of firearms - despite several adequate demonstrations. Then Zavala, the drummer boy, disappeared in the company of some Guaicuras: the Coras reported that he had been killed by them. [40] Shortly after, while the colony was still worried about the disappearance of Zavala, a Guaicura shot a dart at a soldier. Although it did little harm, the offending Indian was placed in the stocks and later confined in bilboes (leg-irons) on the ship. The Guaicuras protested loudly and vehemently. Early in July, a party of Guaicuras came into the settlement, making signs of peace. Fearing that this was either an attack on the colony, or an attempt to rescue their <29> imprisoned tribesman, Atondo ordered them fed. While they were eating, a cannon was fired into their midst, killing three and wounding others, who (most understandably) fled the scene. With "public relations" at a nadir, military morale low, and the supply ships long overdue, the La Paz colony was in a bad way.

On July 15, 1683, the eighty-three colonists boarded the "Almiranta" and sailed across the Gulf of California to San Lucas on Agiabampo Bay, Sonora, where they arrived six days later. The La Paz colonization attempt was definitely a failure.

Neither Atondo nor Kino were ready to give up the idea of colonizing California despite the dismal failure of the La Paz attempt. Two hot and damp months were spent at San Lucas while equipment was gathered and repaired. Supplies were collected from Atondo's capital of San Felipe, Sinaloa, and from the Jesuit missions of both Sonora and Sinaloa. During this time, Blas de Guzmán, captain of the Capitana, sailed into San Lucas with a long, sad tale of misfortunes at sea, due in large part to contrary winds and high seas. However, he also told of a certain Río Grande where he had gone ashore and found the Indians friendly. After many conferences and discussions, this became the objective of the second colonization attempt.

San Bruno Mission Site, Baja California

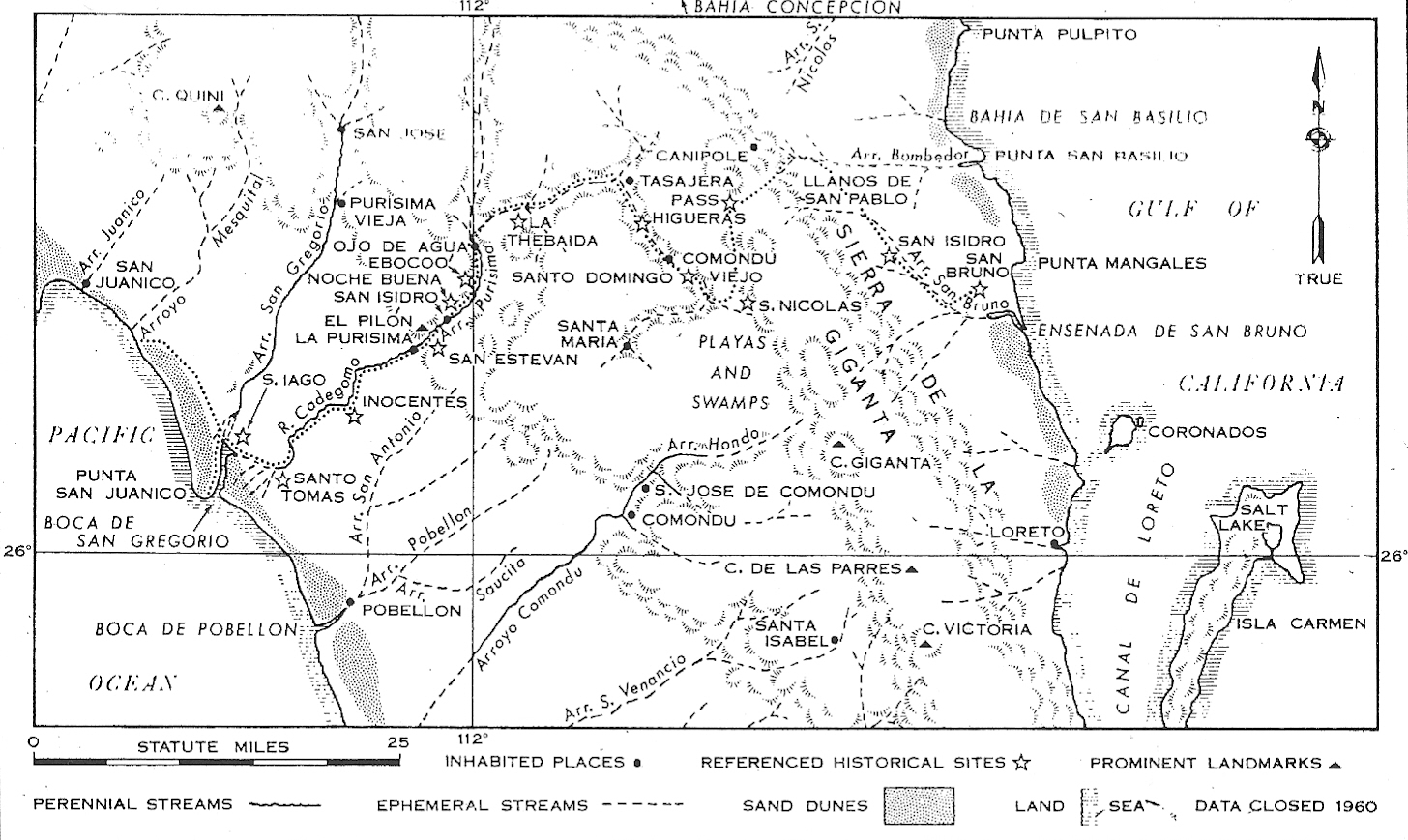

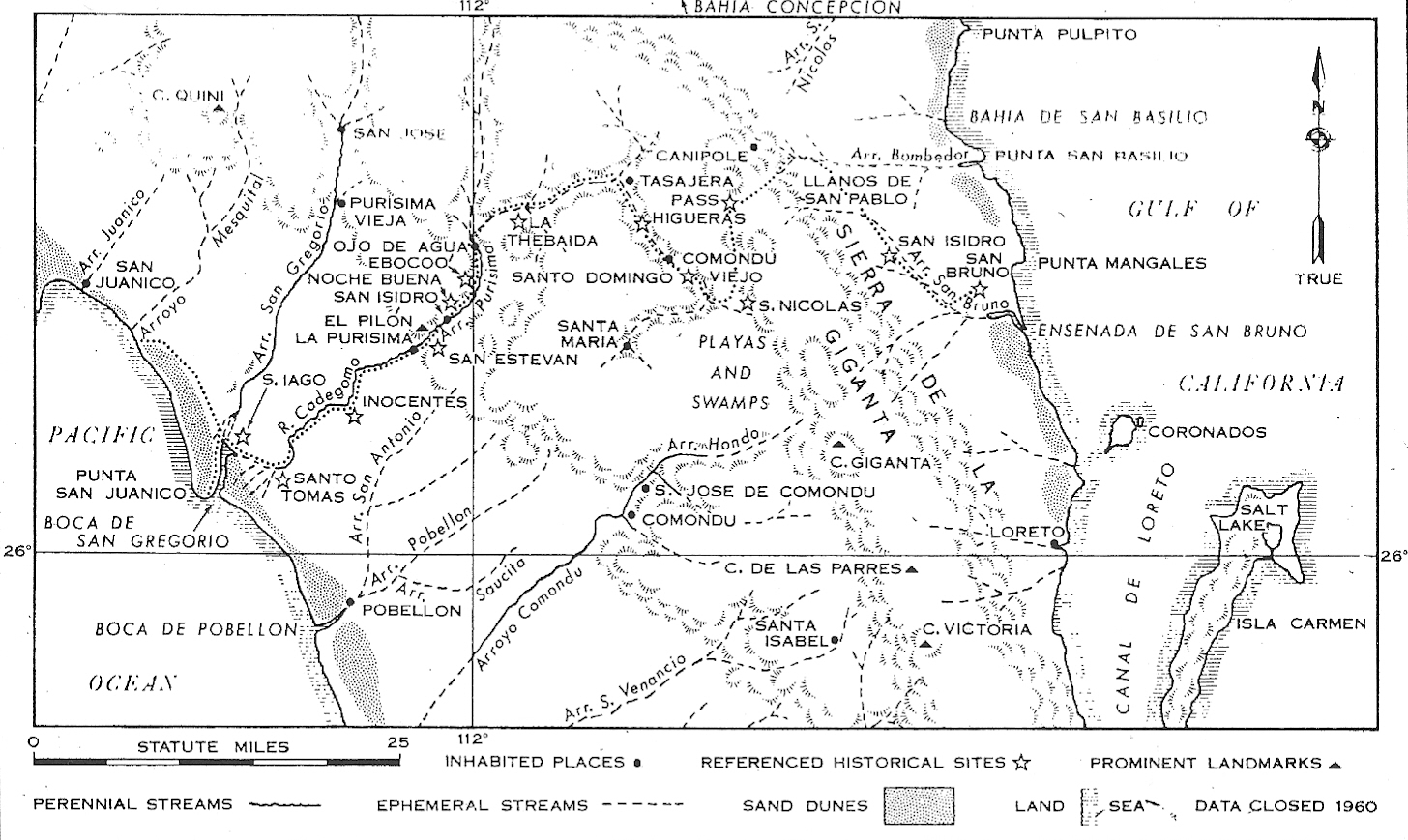

Kino Map of La Paz and San Bruno and Its People

San Bruno on the Rio Grande 1683 - 1685

When all equipment and supplies were readied, the expedition, again in two ships, set sail from San Lucas on September 29, 1683. With the usual fickle winds of the Gulf of California in the fall of the year, it took until October 5 to reach the mouth of the Río Grande. Many unwanted detours from the straight-line course of about 125 nautical miles had been required by the winds. Landing on 'October 6, formal possession of the land was taken with civil and religious ceremonies. Being the feast-day of San Bruno, that saint's name was applied to the area. Consequently, the Río Grande of Guzmán's original report became and remains today the Arroyo de San Bruno. Good water was found about a league up the arroyo; friendly contacts were immediately made with local Indians. Soon a mission and fort were constructed on a low mesa northeast of the arroyo about two miles inland from the river's mouth. The ruins are still visible. While this work was in progress, the missionaries preached to the Indians, and the Capitana was readied for a voyage to Yaqui to get supplies, which included "eighteen pack mules and two dozen wrought-iron mule shoes, with their nails and a thousand nails extra." That voyage of about ninety nautical miles each way was quick and successful. <30>

By December 1 of 1683, the San Bruno settlement was firmly established, and extensive exploration of the surrounding lands began. Several journeys were made up and down the coastal plain, reaching south to the area later known as Loreto. In these explorations, the plain of Londó inland from San Bruno was found, and near a good water hole crops were planted there. The site called San Isidro, later became the site of San Juan Londó, an important visita of Loreto. The facade of the ruined mission building still stood in 1968. Initially, the high mountain barrier of the Sierra La Giganta prevented travel to the west. Eventually passes were discovered and soldiers and missionaries crossed the range with much labor. They reached the great plateau to the west - a relatively flat, slightly dissected area considerably larger than the state of Rhode Island. More than 1,000 feet above sea level, this plateau has a number of shallow (temporary) lakes on the surface. These were full in 1684 as plainly stated in Father Kino's descriptions. With strenuous and extensive field work, aided by Indian friends. Father Kino eventually found a pass by which a mounted expedition could cross the Sierra de la Giganta. He learned of a river on the far west side that flowed west to the South Sea (Pacific Ocean). Soon, Kino and Atondo made plans for an' expedition to that area.

The summer of 1684 was spent in preaching to the Indians, tending crops that didn't grow very well, improving the fort and. church at San Bruno, constructing fortifications and guard quarters at San Isidro, and gathering supplies and equipment for the planned trip to the shore of the South Sea. The supply ships were late, as usual, and fear of starvation at San Bruno was growing very real. Late in the summer, the Almiranta (officially known as the San José) returned to San Bruno, bringing badly needed supplies and twenty additional men, who were ill-trained and poorly equipped. On board was Father Juan Bautista Copart, S.J., a Belgian missionary who had served in the Tarahumara. On August 15, shorty after the arrival of the Almiranta, Father Kino made his final vows before Father Copart. [41]

After discharging its cargo, the Almiranta was dispatched to Yaqui for more supplies. It made four round-trip voyages in rapid succession, bringing to San Bruno supplies, horses, mules, shoe iron, and the myriad other items needed to keep the isolated colony going. The Almiranta was <31> badly in need of repairs after these voyages, so it was sent to Matanchel, a former seaport about three miles east of modern San Blas. Nayarit. On the return to the mainland it carried numerous reports for the viceroy and Father Copart as a passenger. While the ship was being refitted at Matanchel, Captain Guzmán went overland to Guadalajara to get more supplies and some much wanted pearl-divers. Alonso de Zavallos, President of the Audiencia of Guadalajara, furnished the supplies promptly, but had some difficulty finding pearl-divers. Four were eventually located, and in describing them Zavallos wrote "they will set forth within two or three days, for I have kept them in jail in this city in order that they might not flee: they will be escorted to Matanchel under careful guard and custody ... " By March 28, 1685, the ship had returned to San Bruno and brought the much needed supplies together with the apparently unwilling pearl-divers.

While the shipyard at Matanchel was busy with repair work, the colony at San Bruno was also busy. Some of the personnel were at San Isidro where they were trying to raise food crops in poorly watered fields. Many others were away on the long-planned expedition to the coast of the South Sea. Still others were busy with the "house-keeping" tasks at the San Bruno fort and settlement.

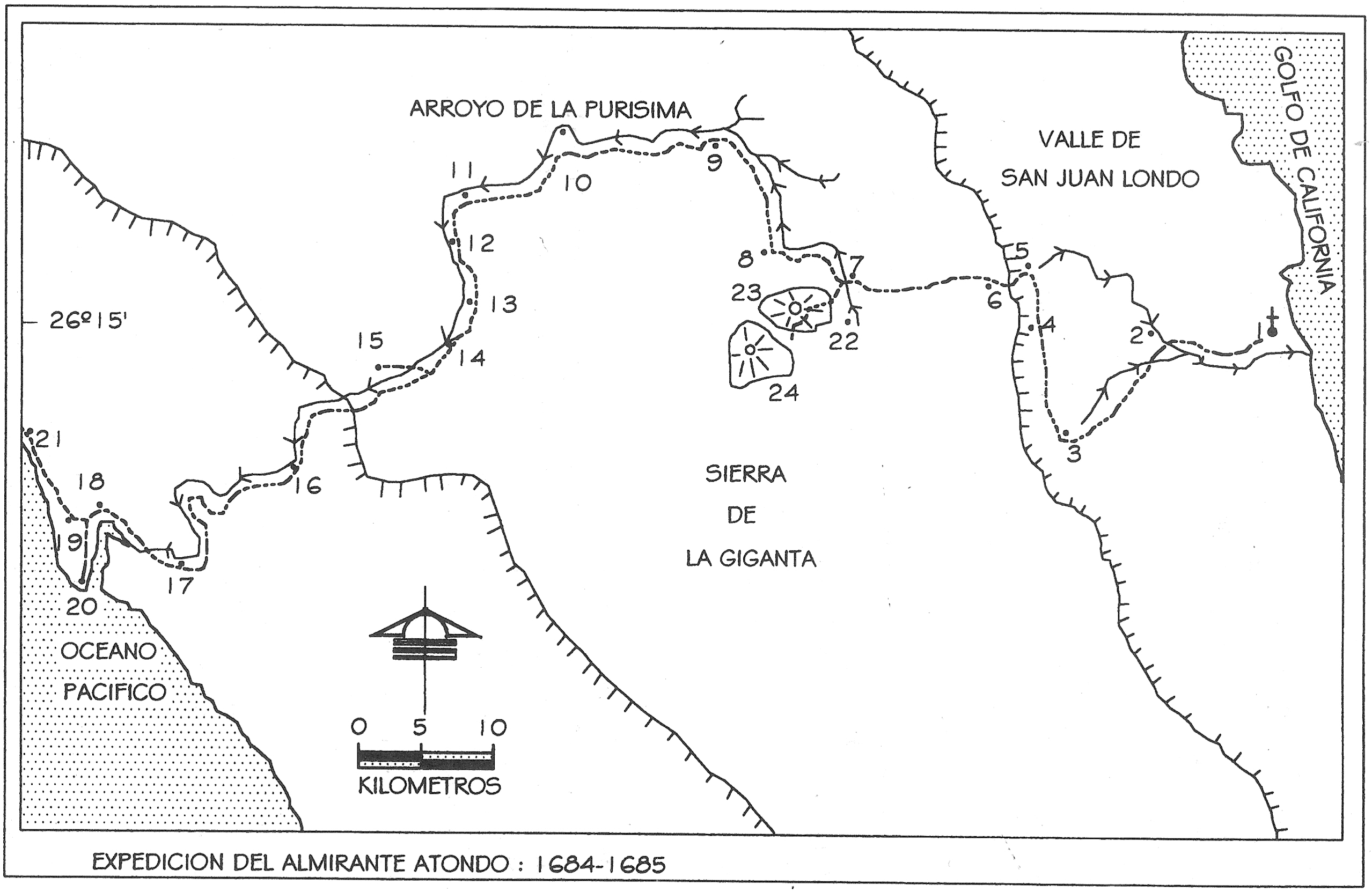

Route Kino-Atondo Party Across Baja California

First European Crossing

December 1684 - January 1685

First by Land To the South Sea December 1684 - January 1685

The expedition to the South Sea was one of the major explorations in the history of Baja California. Personnel included Admiral Atondo, Father Kino, Dr. Castro (the surgeon), twenty-nine soldiers, two muleteers, and nine Christian Indians from the mainland. A varying number of California Indians accompanied to act as guides. The cavalcade included five horses in metal armor, thirty-two horses with bullhide "cueras" (leather armor), thirty pack mules loaded with provisions, two mules ridden by the arrieros, and twenty-two relay animals.

Leaving San Isidro on December 15, 1684, the party travelled northwest to the foot of the pass previously discovered by Father Kino. Here, after much labor spent in improving the trail, they climbed westward to the summit of the Sierra La Giganta, reaching the far side near modern Canípole. Travelling southwest, they came to a canyon and descended into it. This was the Arroyo Comondú in which some years later old mission San José de Comondú was founded. Travelling northwest again, with much labor, they came to the main canyon, then called the Cadegomó and now the Arroyo La Purísima. Down this canyon they rode, mostly westward, struggling over loose boulders and through dense growths of reeds. En route they came to an excellent water <32> hole which they called Ojo de Agua. It is still there and bearing the same name and delivering the same dependable flow. Below and to the west of Ojo de Agua, the party entered the country of the Guimes who tried to turn the Spaniards back. The Indians from San Bruno deserted the party at this point in fear. But Father Kino not only eventually pacified the Guimes, he enlisted their help as guides. Struggling through two more leagues in a maze of boulders and reeds, they emerged at a place they named "Noche Buena" because it was Christmas Eve. It was only a short distance upstream from modern San Isidro. Christmas Day was spent in searching out a better trail, but none was found. More struggles on the day after Christmas brought them into more passable country, and that night they camped at a place they called San Estevan. This was near modern La Purísima. On the 27th, while the main expedition rested and the farriers retreaded the pack and saddle animals, Father Kino with two soldiers climbed a nearby peak to survey the terrain ahead. This they called El Sombrerete "because it had the shape of a sombrero." Today it is known as El Pilón. It is a high butte separated from the main Comondú upland by faulting and erosion. From this summit Father Kino hoped to see the Pacific ocean, but his observations were made uncertain by the fog and haze common in the area during the winter season.

Many of the tired animals were left under guard at San Estevan where the pasture was good and water was plentiful. A smaller party travelled down the canyon to the west by easy stages. eventually coming to the place where the Río Cadegomó joined another river coming in from the northeast. This was named the Río Santiago, now the modern Arroyo San Gregorio. Crossing both rivers, the expedition travelled westward along the north shore of the great embayment at their combined mouths and reached the shore of the Pacific Ocean, which they called the South Sea. This completed the first recorded crossing by Europeans of the peninsula of Baja California. Along the shore, they met some Indians, who were at first timid but eventually accepted gifts. Father Kino especially noted the profusion of shells along the beaches. specifically including the blue abalone, which he later used as biological tracers to demonstrate the possibility of a land passage from California, then thought by many to be an island, to the mainland of Mexico. [42]

Returning to the bay at the combined mouths of the rivers, Atondo wrote a careful description of the harbor on January 1, 1685. and named it La Bahía de Año Nuevo. [43] Today it is known as the Laguna de San <33> Gregorio. After measuring the latitude of the mouth of the estuary which he found to be twenty-five and a half degrees, Father Kino with the rest of the party began the return journey over the outgoing route. [44] Most of the trip was uneventful, but one of the armored horses fell into the Río Cadegomó and drowned; several other horses succumbed to exhaustion. The explorers reached San Bruno on January 13, 1685. [45]

Editor Note: For more about the later significance of the blue abalone shells in Kino's explorations referenced in footnote [42], click

Quest for the Blue Shells - Ives document [pdf]

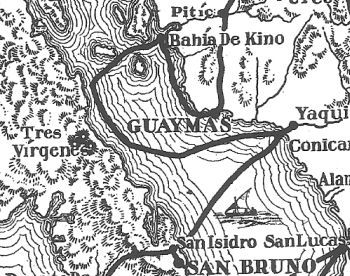

Kino Sails To The Seri People

June - August 1685

Exploring for New Base of Operations June - August 1685

After long after their return, Atondo, who was disappointed at not reaching Magdalena Bay, some distance south of Bahía de Año Nuevo, went on another exploring expedition, accompanied this time by Father Goñi who had become expert in the Edu language, spoken to the south of San Bruno. [46] Journeying south along the east shore of the peninsula, <34> they searched for a pass over the Sierra La Giganta but found none. Although they travelled roughly 100 miles south of San Bruno. they found no way over the mountains and eventually turned back to San Bruno where they arrived on March 6, 1685.

Slightly more than two weeks later, the Capitana arrived at the isolated outpost, bringing badly needed supplies and the long hoped for pearl-divers. With its repeated crop failures. the colony was in a bad way. Several soldiers had died of scurvy, and many more were sick. At one roll call, when sixty-nine soldiers should have reported, only fifteen appeared. Thirty-nine were too sick to appear, and four were reported dead. After a long conference, it was decided to abandon San Bruno, at least temporarily. The sick were to be taken to the Yaqui missions for care. Admiral Atondo and Father Goñi were to take some of the able bodied men in the "Balandra" to hunt for pearls. Captain Guzman and Father Kino were to sail in the Capitana to look for a better mission site. On May 8, 1685, San Bruno was abandoned. [47]

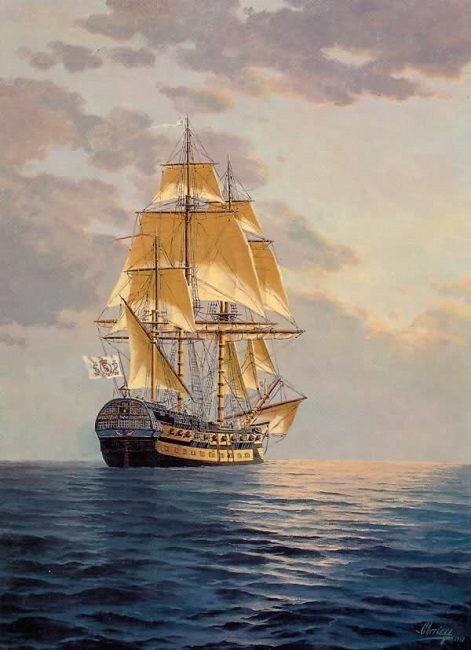

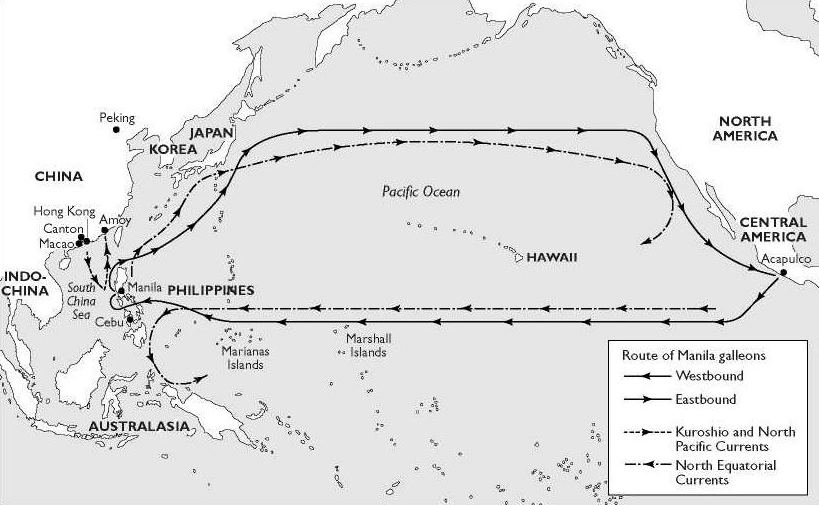

In accord with previous plans, the sick were taken to the Yaqui missions on the mainland where most of them recovered. Admiral Atondo and Father Goñi hunted for pearls with little success - the total catch being "two ounces and two drachms." Captain Guzman and Father Kino explored the upper gulf visiting, among other places, Tiburon Island, then and now the home of the Seri people. In September, 1685, the two ships rejoined and sailed for Matanchel; both were badly in need of supplies. Promptly, Father Kino went to Guadalajara to arrange for further missionary efforts in California, and soon Admiral Atondo journeyed inland for the same purpose. Both achieved apparent success. Returning to Matanchel, the principals prepared for further missionary exploration, but suddenly they were diverted by orders from the viceroy, who dispatched them to sea to intercept the Manila galleon and warn it of pirates along the coast.

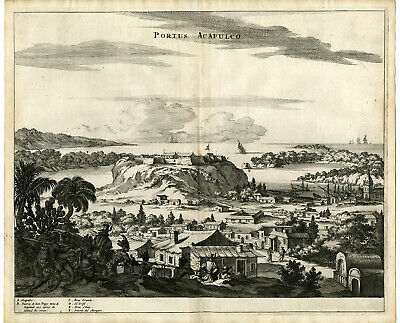

Manila Galleon From Phillipines to Mexico

Acapulco - New Spain's Manilla Galleon Port

1761 Engraving

Diversion by Pirate Threat and Kino's Advocacy for Jesuit Return 1685 - 1697

Leaving Matanchel on November 29, they intercepted the galleon a day later. Sailing out of sight of land, they convoyed the galleon to Acapulco, successfully evading the pirates, who were ashore raiding coastal settlements for provisions. [48] After this successful rescue, Kino and Atondo went to Mexico City where further plans for California were made. The needed funds were promised and seemed available. Then, troubles began. A revolt was threatening in Nueva Vizcaya which would require funds and soldiers. Spain urgently needed half a million pesos from Mexico to help pay a French indemnity. So the funds for California <35> were no longer available, and the carefully planned enterprise ground to a halt. No more efforts to colonize California were made for more than a decade. Father Kino was assigned to Sonora where he labored effectively, for the rest of his productive life. Admiral Atondo disappears from the field of our interest.

Although the Kino-Atondo expeditions did not achieve their planned objective - the founding of a permanent settlement in California - the work done by the party was of inestimable value to later workers there. Friendly relations were established with several tribes on the eastern side of Baja California; the vocabularies of the Cochimí language prepared by Father Kino and of the Monqui language prepared by Father Copart were of inestimable value to those who came later to the barren peninsula. The maps prepared by Father Kino and his developing ideas regarding an overland passage from the mainland of Mexico to California influenced geographical thinking and exploration plans for more than three-quarters of a century. [49] Thus, although the expedition might be rated a failure, it actually laid the foundations for later missionary successes and led to the eventual settlement of the California's, both Alta and Baja.

For slightly more than a decade the California mission field was entirely deserted because no funds or workers were available. The civil authorities had correctly determined that California, as then known, could not produce enough pearls, metals, or agricultural products to pay for its occupation. During this time Father Kino, who had now been assigned to the Pimería Alta, had founded several missions which became relatively prosperous. The surplus products of these missions, according to Father Kino's reasoning, could be used to help the conversion of California. In 1691, by order of the Father Provincial, Ambrosio Oddón, Father Juan María Salvatierra was sent from his mission at Chinipas to make an inspection of Pimería Alta where Father Kino was <36> working. During their travels together Father Kino "sold" Father Salvatierra on the need for reestablishing the California missionary effort, and thenceforth, despite years of apparently fruitless endeavors, both worked toward that end. In late 1696 and early 1697 plans were made for another California expedition to be financed by private gifts, as no funds were available from the royal treasury. Eventually these private gifts became the famous Pious Fund, which apparently started with the donation of one peso, but grew until it became the major support of the California missions.

At this time Kino and Salvatierra were joined by Father Juan de Ugarte, S.J., of whom we shall hear much more later. Soon, an agreement was worked out with the viceroy by which, so long as no public funds were spent, the Jesuits could make another attempt to colonize California, even to the extent of hiring their own soldiers (provided the Jesuits met the payroll). This agreement with only very minor changes prevailed throughout the Jesuit occupation of California, and, in general, worked very well. This lasting rapport between the Jesuits and the military may stem, in part, from the early military experience of St. Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuit Order.

The viceroy's permission and agreement were dated February 5, 1697. The next day Father Salvatierra started for the west coast. En route he visited Father Juan Bautista Copart to obtain the information which he had collected during the Kino-Atondo expedition of the previous decade and the grammars of the Indian languages he so carefully prepared. While awaiting the arrival of ships, supplies, and Father Kino on the Sinaloa coast, Father Salvatierra made a quick trip inland to Chinipas, where he became involved in a minor Indian uprising. Returning to the west coast, he made contact with the ships, gathered supplies, recruited soldiers, and finally sailed from Yaqui on October 10. Father Kino, however, was not with him. Because of unsettled conditions in Sonora, he was ordered to remain there because his presence was" considered to be worth a thousand soldiers." In his place, another hard working and successful missionary, Father Francisco Maria Piccolo, S.J., was chosen. [50] <37>

The tiny expedition suffered the customary problems in attempting to cross the Gulf. Adverse winds blew the ships aground and created repeated delays. Finally, however, the miniscule fleet reached the eastern shore of the peninsula and undertook some limited coastal exploration. They visited the ruined site of Kino's mission San Bruno and then decided on going ashore at the Bay of San Dionisio, where they were greeted by Indians who had known Kino and Atondo. On October 19, 1697, they started clearing the mesa; animals and supplies were unloaded and a corral was built. Even an Indian attack was repulsed. Chief Dionisius, who was suffering from an apparent cancer, was instructed and baptized. Work was begun on the mission and camp of Loreto, which would later become the military and mission center of Baja California.

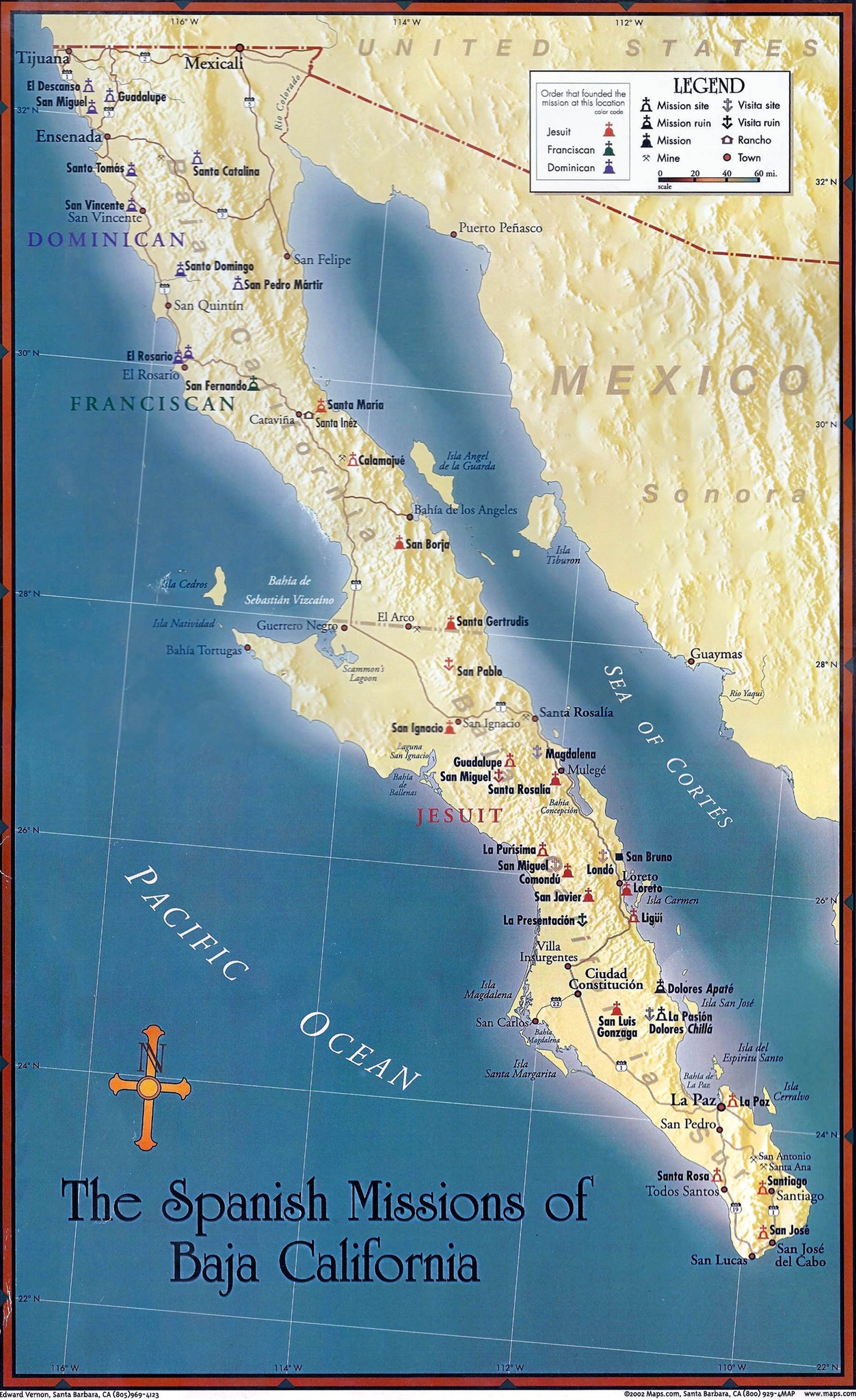

Missions of Baja California 1697 - 1769

Kino's Sonora Supports Restarted Baja Missions 1687 - 1711

[Thereafter] California had experienced slow settlement, largely by Jesuit missionaries and the few soldiers who accompanied them. Settlement began in the southern part of the peninsula, now the State of Baja California Sur, and very slowly over the next three quarters of a century crept northward into what is now the State of California. Missionary activities in the arid and sterile peninsula of Baja California were constantly inhibited by lack of missionaries and soldiers, insufficient funds, shortages of all sorts of supplies and manufactured goods, and very serious transportation difficulties inherent to the use of sailing ships in an area of undependable or contrary winds. These conditions led Father Johann Jakob Baegert, S.J., of mission San Luis Gonzaga to comment that California ·"of all the countries of the globe is one of the poorest. "[36]

Because of the aridity and sterility of the peninsula of Baja California, the missions there were never economically self-sufficient and help from "outside" was needed during the entire mission period. Each mission had a garden which produced some fruit and vegetables, and a few also produced grain in good years. The area of the garden was determined by the amount of level land near the mission; the output of the garden was limited by the amount of irrigation water available. At some of the missions there was considerable crop" shrinkage" because of the "'taking ways" of the natives, who apparently learned what was good to eat rather rapidly, but assimilated the commandments much more slowly. The missions also had herds of livestock - horses, mules, cattle, sheep <26 photo> <27> and goats - which supplied some of the needed meat, leather, and wool. Because of poor forage and native depredations these herds were not as productive in Baja California as similar herds were in Sonora. Deficiencies of meat and grain were normally made up by generous donations from the relatively prosperous missions of Sonora. [37] Manufactured goods and comestibles not available from Sonora, such as chocolate, were purchased in Mexico and shipped by land and sea to Baja California. Payment for these goods was usually made through the Pious Fund, although few royal grants assisted in their shipping. [38] Transportation costs of goods purchased in Mexico commonly exceeded the purchase price, and many cargoes destined for the missions were lost at sea or spoiled in transit. In consequence, Baja California prices were more than double those on the mainland.

Ronald L. Ives

Excerpt from Historical Summary

"José Velásquez: Saga of a Borderland Soldier" 1984

To Download and print entire chapter article by by Ronald L. Ives, click

Kino in California document (text)

Kino's California Entradas

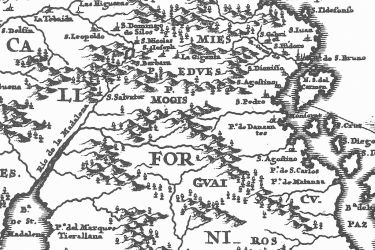

Kino's 1685 Map - Detail

Sierra La Gigante Range From The Sea of Cortez

Kino's Explorations of Las Californias and Voyages on The Pacific Ocean

Kino's Entradas Beyond The Giantess

November - December 1683

Herbert E. Bolton

The San Bruno settlement had been founded. The formal act of taking possession of the province of San Andrés on November 30 by Atondo for the Crown in the name of Carlos Segundo and by Kino for the Church in the name of Bishop Juan, put a period to this paragraph in the history of "the largest island in the world." The Admiral and the Rector were now free to undertake the more ambitious exploration into the interior which for many days they had been planning.

They sallied forth on December 1. For this longer journey they had more elaborate equipment than for the "Primera Entrada." Besides the Admiral and Kino, head and soul of the enterprise, there were twenty-five soldiers, six Indians from Mayo, six of the Edu nation, Dionisio's people, and six Didius, Leopoldo's men. There were fourteen horses, five of them armor-covered and fierce-looking, and six pack mules carrying provisions for a twelve days' journey. Camp was left in charge of Captain Guzman and Father Goñi. On the Capitana at Coronados Island remained Alférez Lascano with ten sailors and deck hands.

The knights rode out, followed by the footmen. Three leagues northwestward took them to the fine water and pastures of San Isidro. This place, called Londó by the Edues and Cathemeneol by the Didius, was the spot where later was built the mission of San Juan Londó, whose picturesque ruins are still well preserved. Here they camped and were visited by natives. Five of them, all Didius, joined the expedition. They must have pronounceable names, so Kino called them Vicente, Santiago, Juan, Andres, and Simón.

In the "Primera Entrada" Kino and Atondo had continued northwest up the level valley that led to the plains of San Pablo. [Editor Note: Kino called the San Pablo journey made in November 1683 the "Primera Entrada." San Pablo is located six leagues northwest of San Bruno]. This time the adventurers set for themselves a far more difficult task. They planned now to swing west and scale the precipitous sierra that hid from the narrow coast plain the mysterious region that lay beyond land of giants the natives said. Both the giants and the sierra gave zest to the exploit.

The way up the lofty wall of rock, that was the first question! The Indians said they could answer it. Guided by the five Didius, Atondo went four leagues to a fine spring which they named San Francisco Xavier, for it was the eve of the Feast of St. Francis. On the way the Indians gathered for the explorers luscious pitahayas, which were still in season there. The water at San Xavier was worthy of comment in that arid land, for it actually flowed. "We were very much pleased," wrote Kino, "to see the first running stream in this California, for this water hole" - he called it an "aguaje -" had this quantity of water. We gave rewards and presents to the Indians who showed it to us"- and well they might, for such a rarity -"and they as well as we were very much pleased. We noticed and learned that many Indians lived here for some months of the year although there were none now. Kino saw in this fine water supply another mission site. Here at San Xavier siesta was taken, camp made for the night, and great smoke sent up to let the people at the settlement know of their safe arrival. The place was near two conspicuous peaks which were in plain view from San Bruno, and indeed, from fifteen leagues out at sea. To dedicate the fine site to the spiritual conquest a large cross was erected.

The mountain wall was now towering close ahead, and in the afternoon five men went forward to find a trail between the two peaks for the next day's march. At night the scouts returned. After having advanced two leagues they had found water holes and a large carrizal or reed marsh, but they had encountered, just beyond, a mountain cliff so steep that horses and mules could not ascend. If Atondo could not go straight ahead he might go around. So next morning he approached the range by a different route. But it was of no use. After ascending the lower slopes for some two leagues, the same distance the explorers had covered, they reached cliffs and crags which the animals could not pass. The prospect was discouraging.

Scouts were again sent out, now in two parties, Contreras with five men and Itamarra with four. Contreras sent back a note to report that the ascent was impossible for horses and difficult for men. But the climb was worth it, for there, a league above the horsemen, beautiful plain lay before them. It was now evident that the horses must be left below. This was tough on a race of men born to the saddle. But there was no help for it. So Atondo sent food up to the scouts, telling them to remain over night on the mountain top. He would follow on foot.

Next morning they made the plunge. Leaving the horses and mules in charge of six men, the rest set forth. Each one carried, besides his weapons, his own pack of supplies for three days. Kino's youthful prayer for a "difficult mission" was being answered. And what better sport could he wish? Twenty-nine men, besides five heathen Indians, made the start. For a league they scrambled like flies up the face of the bare mountain wall of living rock; in places even the nimble Indians had to crawl on all fours. Three or four spots, called the "Passes of Santa Barbara," were so bad that it was necessary "to haul up by a lariat not only the munitions and provisions, but also the Admiral and others." I cannot believe that Kino was one of them. Each reader will have to rely on his own imagination for the picture presented by Atondo as he dangled from the cliffs.

The start had been early. The winter sun had barely showed its face when the puffing band reached the top. From a miraculous occurrence of the day before, the spot where they gained the summit was called Santa Cruz. The scouts had thrown down a dry cardón tree, a species of tall, straight cactus which flourishes there in veritable forests. "When it fell on the ground a limb was so imbedded that with the trunk it formed a cross, as if it had been made on purpose with the hands, and it was set up and venerated and left in that position."

It was now that the rugged sierra was given the name by which it still is known. "Because it is so very high," Kino writes, "for at sunset it can be seen from Hiaqui, and likewise because a few days ago some persons said and believed that in these lands of the Noys there were giants, we called the range La Giganta." And La Giganta it still is both in fact and in name. The Giantess rises six thousand feet almost sheer out of the Gulf.

The view was worth the climb. The scouts had not exaggerated. Facing westward from Santa Cruz the exhilarated explorers looked out on the "beautiful and most pleasing plains," of which Contreras had told. These llanos, too, already had a name, for, says Kino, "since yesterday, because they were discovered on the day of the glorious Cherubim, they have been called the Gift of San Francisco Xavier" Dádiva de San Francisco Xavier.

Westward Ho! They were now in the land of the Noys, country of the giants. ….

But Kino was curious to know what was beyond the mountains over which the natives had scampered. The result was a division of the party. Atondo decided to camp here beside the refreshing lake, while the strongest men went forward, equipped for two days' travel, one going and one returning. Kino was one of the strongest, both in heart and limb. …

Three of the "strongest," Kino, Itamarra, and Bohórques, scaled a high cliff, and from it they saw, both with and without a telescope, "another pretty lake, and a large plain, and many other hills, sierras, and plains, stretching more than twenty leagues toward the north." Descending from the cliff and traveling northwest over the country at which they had gazed, all took siesta at the lake, "and drank from its most beautiful and crystalline water in the shade of some large fig trees and of a cliff." These fig trees were evidently tunas. The lake was five leagues northwest of the camp where Atondo had been left to sleep and rest. It was northeast of and not far from the present Comondú. …

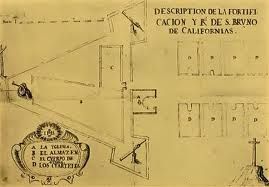

Kino and Atondo now prepared reports and wrote letters to their friends. Kino drew a plan of the fort, church, and barracks, and made map of California, showing the settlements at La Paz and San Bruno, and all the principal explorations thus far accomplished. It bears the date December 21, 1683. The original is still preserved and is one of the world's cartographical treasures.

The text set out above is an excerpt from Bolton's account.

For the entire Text of Chapter 8 - Farther Afleld

and its sections: The Face of the Giantess; The Gift of San Xavier;

The Strong Go Forward and A Pass Through the Sierra.

Dr. Herbert E. Bolton

Chapter 8: Farther Afield

Rim Of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino - Pacific Coast Pioneer 1936

The text set out above is an excerpt from Bolton's chapter account and its sections:

"The Face of the Giantess"; "The Gift of San Xavier"; "The Strong Go Forward and A Pass Through the Sierra."

For entire chapter account, click

Farther Afield - Bolton document (text)

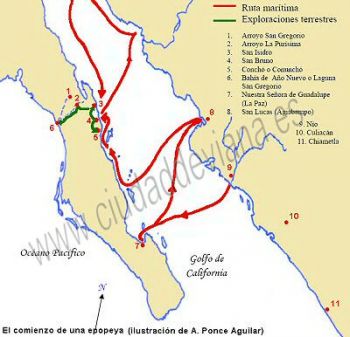

Primera Entrada al Interior de California

December 1684 - January 1685

Carlos Lazcano Sahagún

"La primera entrada: descubrimento del interior de la antigüa California"

List of sites and places that appear in Admiral Atondo's diary. In parentheses are the current names.

1. Real de San Bruno (San Bruno): 2. Real de San Isidro (San Juan Bautista Londó): 3. Santa María Nebocoxol (rancho San Francisco de Asís): 4 San Gabriel Bunmedojol (arroyo el Álamo): 5 Santo Tomás Cupemeyeni (arroyo Nacojoa): 6. Cuesta Trabajosa (cuesta de Nacojoa): 7. Nuestra Señora de la Comondú (Comondú Viejo): 8. Santo Domingo de Silos (rancho el Aguelión): 9. Las Higueras o Meyitesircongo (las Higueras): 10. La Tabaida o Gaelvxu (Poza del Gallo): 11. Ojos de Agua (Ojo de Agua): 12. San Delfino de Pamplona Ebocoo (rancho Huerta Vieja): 13. Puesto de Noche Buena (El Zacatón): 14. San Esteban (Carambuchi): 15. Cerro Sombrerete de San Juan (Pilón de La Purísima): 16. Los Inocentes (?): 17. Santo Tomás de Cantuaria (Poza Larga): 18. Real y río de Santiago (arroyo San Gregorio): 19. Estero (Estero de San Gregorio): 20. Boca del Estero (La Bocana): 21. Salina de San Silvestre (?): 22. Aguaje (rancho Cambalaqui): 23. Llano (llano Redondo): 24. Cerro sin nombre (cerro el Picacho). Map by Carlos Lazcano Sahagún from his book by "La primera entrada: descubrimento del interior de la antigüa California", 2000

Cerro Sombrerete de San Juan (Pilón de La Purísima)

First Across The Peninsula

December 1684 - January 1685

Herbert E. Bolton

The expedition was made as planned, in spite of all handicaps and doubts. On December 14 the Almiranta weighed anchor and sailed for Mexico. On the same day Atondo and Kino rode to San Isidro, the rendezvous where men, provisions, horses, and mules were assembled. Next day the start was made.

It was an interesting company that marched northward that mid December day. Besides the Admiral, Father Kino, and Dr. Castro the surgeon, there were twenty-nine soldiers, two muleteers, and nine Christian Indians from the mainland, a total of forty-three persons. In addition there was a following of California natives to serve as guides. Kino with his astronomical instruments was prepared for his duty as cosmógrafo. He and Contreras were the principal interpreters. The soldiers wore cueras, or leather jackets - marvelous armor of bull hide. Each carried a shield, arquebus, a pound of powder, a hundred bullets, a hundred slugs and a calabash for a drinking cup - the cumbrous outfit of which the Admiral had complained.

There were five armored horses led "de diestro," in good medieval style, for Atondo had brought from San Lucas that many suits; of metal horse armor. There were thirty-two light-armored mounts in bull hide cueras, thirty pack mules loaded with provisions, two mules ridden by the arrieros, and twenty-two relay animals, a total of ninety-one mounts and sumpters. No wonder the natives fled when they saw such a cavalcade coming. In the packs there was a goodly supply of little wares, especially cowhide moccasins, called catles or cacles, to serve as presents for the Indians. |183|

As they passed through each village Kino and Atondo made a distribution of these gewgaws, and the guides were encouraged to broadcast a story of Spanish generosity. Nearly every day after camp was made, a squad of soldiers and Indian laborers were sent ahead to explore the road for the next day's march. Frequently the going was so bad that these pioneers had to spend hours, and sometimes an entire day, in opening a trail, cutting down trees, prying rocks out of the way with crowbars, filling holes, or leveling steep pitches. Often Kino, accompanied by two or more soldiers, climbed some commanding peak, in order with his telescope to learn the nature of the country, look for smokes of Indian villages, and prospect for signs of precious metals. As they neared the western side of the Peninsula the chief aim of these observations was to catch a glimpse of the majestic South Sea.

One of the greatest difficulties of the journey was that of the horses' feet. The Admiral's fears were justified. The road was rough and terribly stony, and the animals often went lame. Horseshoeing was an almost daily business, and more than once a whole day was spent in camp to rest the animals and repair their shoes. More than one poor mount played out and was abandoned by the wayside as food for the hungry natives, who left nothing for crows or buzzards. The caballos did their part in the expedition. Timid though they were, the Indians several times disputed the passage of the Spaniards, as Moraza had feared they would do, but with presents and "good talk" they were won over, and they performed incalculable service as guides. Frequently the Spaniards were followed by troops of natives from one village to the next. The women especially were friendly, and sometimes made trouble for the commander.

The itinerary and the incidents of the journey can merely be summarized here. Only the full diary which was kept can do the adventure justice. And only one who has retraced the expedition can read |184| the historic journal with full measure of understanding. Till the explorers had crossed the Sierra Giganta they followed essentially the trail taken by Kino and Contreras the year before - when young Eusebio trotted behind and the little black crow was mascot.

Four days after leaving San Bruno the cavalcade arrived at Santo Tomas, the arroyo by which Kino and Contreras had crossed the mountains. With the heavy pack train the traverse now was a more difficult undertaking than it had been before, and Atondo halted a day to prepare the road. Adjutant Chillerón with ten soldiers and four Sinaloa Indians performed the back-breaking task. Equipped with picks and axes, they went ahead and spent the day cutting trees, removing rocks, and filling bad holes. When they returned in the evening they were a tired band. That night Chief Leopolda came to camp. Atondo gave him presents, and Kino urged him to send messages ahead, telling his people of Spanish friendship and especially of generous presents. Leopolda complied and thus rendered useful service. Moraza had misjudged him.

Early next morning the explorers sallied forth up the steep. In spite of all the road building of the day before, the loaded pack animals had a hard pull, "and although each soldier went up on foot assisting a mule, some of the animals did not fail to fall down." La Cuesta Trabajosa - the difficult climb - they very appropriately named this acclivity. Six toilsome leagues were covered that day, to an arroyo which the natives called Comondé. It was the Comondú, an affluent of the present Arroyo Purísima. Camp was in the vicinity of San Nicolás, the village visited by Kino and Contreras the year before, for thus far they were on their former trail. Among the natives familiar faces were seen, and friendly smiles of recognition.

Three grueling days were now spent descending this arroyo to the forks of the Purísima. Whoever has been in that rough country will not find this difficult to believe. For two of these days the camp was followed by friendly Didius, including "five pretty young women" brought by the rascal Leopoldo, who thus raised a new problem of discipline for Atondo. It was the Admiral who thus described the damsels. On the subject Kino was discreetly silent. Camps were made at Santo [185] Domingo, Las Higueras (still on the map in the same vicinity) and La Thebaida - the Theban Desert. On this stretch they passed the canyon site of the later founded mission of Old Comondú, Here in this desolation began the territory of the Gümes , thirty of whom were met and given presents. In return their chief gave Atondo "a little toque of nacre which they use to bind up their hair." The Admiral probably did not wear it.

A pleasing sight now met their eyes. Two leagues down the arroyo on the third day took the explorers to "some springs of water which form a river. According to a report which the natives gave us, although it has not rained in fourteen months, it carries so much water that there is more than enough to run a mill." Man and beast alike now drank to satiety. The place was the one still called Ojo de Agua the spring - at the forks of Arroyo de la Purísima. It is an unmistakable landmark in that unslaked desert, and an eternal joy to the thirsty.

Here Atondo's route swung sharply southward, down the river, and the country became rougher than before. Even yet no wagon road traverses it, and when in 1932 I told my local guide where I was bound, he looked dubious and shook his head. Three leagues farther on, fifty-four Gümes appeared on the trail and tried to turn the Spaniards back. The soldiers bristled, but Kino came to the fore. He had weapons more powerful than sword or blunderbuss. "With the good words which were spoken to them by the father superior ... and by showing them catles and other wares" they were soon won over. …

Now for the climax of the adventure! Now for the South Sea!

Father Eusebio never forgot those blue shells. Years later they became a central factor in another drama in which he played the leading part. "

Dr. Herbert E. Bolton

"Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino - Pacific Coast Pioneer"

Chapter 11: First Across The Peninsula 1936

pages 182 - 190

The text set out above is an excerpt from Bolton's chapter account. For the entire Text of Chapter 11 - First Across The Peninsula and its chapter sections: River of San Tomas and The South Sea, click

First Across The Peninsula - Bolton document (text)

Atondo-Kino Exploration Map Across Baja California

Cartograpy by Ronald L. Ives

Kino's Route Across Baja California

December 1684 - January 1685

Ronald L. Ives

e first recorded crossing of Baja California, which took place in 1684-85, was by a Spanish exploring party under the direction of Don Isidro Atondo y Antillón. One of the members of this party, and one to whom most of its success can be attributed was Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J. Through the use of historical documents and maps, most of which are a result of Kino's efforts, it has been possible to trace the route of the party more accurately than had formerly been the case. Much of the recent success can be attributed to exploration and description by geologists and botanists and to the fact that maps of Baja California have been greatly improved by aerial photography.

The first recorded crossing of peninsular California, accomplished in the winter of 1684-1685 by a Spanish party led by Don Isidro Atondo y Antillón, became a successful exploration, rather than another "blundering through the wilderness," largely because of the inclusion in the party of a trained cosmographer, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J. The major part of our knowledge of this early and important exploration comes from the diaries and maps so carefully prepared by Father Kino, although confirmatory evidence is found in the Atondo diaries. parts of which were apparently written by, or in collaboration with, Father Kino.

Many of the maps and documents concerning this expedition were discovered by the late Herbert E. Bolton, who also collected, indexed, and summarized all material concerning it (Bolton 1936: 182-90). In company with his son Herbert E. Bolton, Jr., Dr. Bolton made extensive field studies in Baja California, incontrovertibly demonstrating the accuracy of the original accounts and recovering many of the pertinent ancient sites.

Despite the great competence of the Bolton investigation, the route of the Atondo-Kino expedition across Baja California is still somewhat of a mystery to many historians. Not only is Baja California poorly known and inadequately mapped, but many place names have changed, and the general environment, particularly at the time of Bolton's [17] investigation in 1934, was little understood.

Keenly aware of these unavoidable deficiencies in Bolton's work, the late Peter M. Dunne. S.J. made extensive studies of the Baja California environment, which he summarized as the first chapter in his work "Black Robes in Lower California" (Dunne 1952: 1-25). Since the writing of Father Dunne's summary, maps of Baja California have been very greatly improved (Gerhard and Gulick 1958), largely by use of aerial photography; the geology of the peninsula has been investigated with some thoroughness (Beal 1948), and an exhaustive report on the flora of the arid tongue of land has become available (Shreve 1951) .

As a result of these multiple advances, it is now possible to describe Kino's route across Baja California in terms of modern available maps, and to identify the various campsites in terms of modern names with some hope of correctness. The study to be reported here made use not only of published data sources, but also of field checking, both on the ground, and by means of several flights over the areas concerned.

The major part of the Kino-Atondo itinerary across Baja California is shown on Kino's map "Delineatio Nova et Vora Partis Mexici, cum Australi Parte Insulae Californiae -- " (Scherer 1703: Bolton 1936: 192), a pertinent section of which comprises Fig. 1. Note that the draftsmanship of this map is not Kino's, the original having been redrawn, prior to 1703, for purposes of publication. perhaps by the engraver.

The expedition travelled from San Bruno, on the present arroyo San Bruno, to a point near the present Punta San Juanico, on the Pacific coast. crossing some of the most difficult terrain in North America.

Ronald L. Ives

Kino's Route Across Baja California

Kiva April 1961

To view and download the entire article "Kino's Route Across Baja California", click

Kino's Route Across California - Ives document (pdf)

Kino Plan Of Using Gulf Islands as Stepping Stones To Return To California

Island Stepping Stone Return Plan

"Kino en California: 1681-1686"

Gabriel Gómez Padilla

Gabriel Gómez Padilla

"Kino en California: 1681-1686"

Espiral (Guadalajara), 21(61), 145-190. 2014

Spanish

Click →

http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-05652014000300006&lng=es&tlng=es.

Resumen

En este artículo se plantea un doble propósito: exponer la participación del jesuita en la expedición de Isidro Atondo y Antillón a la Baja California y rendir tributo académico a la memoria de Miguel Mathes por su labor documental sobre Eusebio Francisco Kino. Se tratan los intentos de la Corona española por colonizar California y también se ofrece una breve biografía de Atondo para contextuar los documentos usados, los cuales van desde las capitulaciones de Atondo hasta la implementación del proyecto seri, ideado por Kino para luchar por el derecho de los californios a ser evangelizados.

For quick English translation using either

Google and Microsoft translation programs

Find and Click on "Traducción Automática" link in the right menu.

Abstract

The article by Gabriel Gómez Padilla has discusses the participation of the Jesuits in the Atondo and Antillón Expedition to Baja California and pays tribute to the memory of Dr. Miguel W. Mathes (1936-2012) who was the leading U.S.scholar on the history Baja California. Dr. Matthes was the key researcher the documentation of Kino's work in the Baja missions.

The article also discusses the previous attempts of the Spanish Crown to colonize California and contains a brief biography of Isidro Atondo and Antillón. The documents range from Atondo's agreements with the Spanish Crown at the beginning to the end of the effort with Kino's "Seri project" - Kino's first plan for return of the Jesuits to Baja [using Gulf islands as stepping stones].

Manila Galleon Approaching Baja California Coast

California Vision, Pirates and The Manila Galleon

Manila Galleon in the Philippines Preparing to Set Sail For Mexico

California Departure and Kino's Return Prevented By

Pirate Threat To Manila Galleon 1686

Ernest J. Burrus

Obviously, the little [Baja] colony could not live on greater geographical knowledge and on hopes for a brighter future. They had to find more suitable and productive localities, if they were to survive. ...

The discouraging past, the uncertain present, and the unpromising future, all conspired to dismay the bravest soldiers and even Atondo himself. Only Kino pleaded to hold out a little longer or at least to try another locality in the vicinity. He volunteered to explore for an appropriate site. He pleaded that they should not completely abandon the area where he had already instructed so many natives. His plea was in vain. The decision had been made to cross over to the Mexican mainland, replenish the depleted supplies from the Jesuit missions in the Yaqui valley, and then recross the Gulf in order to explore the peninsula farther to the north. ....

Although probably no one said so, Lower California had been abandoned by early May of 1685. It was not destined to be settled permanently until October, 1697, when Father Juan Maria Salvatierra would sail into the bay of San Dionisio and establish the mission and town of Nuestra Señora de Loreto.

Kino now sailed with Atondo to Matanchel, near Chacala, from which the little fleet had weighed anchor so proudly and confidently more than two years previously. From Matanchel Kino hurried overland to Guadalajara, and there poured out his grief to Bishop Garabito because of the abandonment of Lower California.

He was requested by civil and ecclesiastical authorities to draw up a report. In doing so, he did not waste his time blaming Atondo or anyone else. He did review the past, but only to point out what should be corrected; his emphasis, however, was on the future: how the California enterprise could be effectively and successfully re-activated. The report: was his first comprehensive "vision of the future ". ...

Missions and forts, Christian Indians and soldiers, violence and the Gospel, did not mix well. Ranches and farms would raise the economic and social status of the natives and make the missions independent of state aid and control; they would help to win over and hold the Indian population. Smaller and more maneuverable boats, supplemented by a feasible land route, could provision Lower California far better and more economically than the bulky and unwieldy ships engaged in hauling supplies from distant ports. He would make friendly natives his best allies and most effective defenders against hostile intruders. He would even show enemy tribes the advantages of a better and more secure way of living. He would explore more fully and accurately than any of his predecessors; above all, in the areas visited, he would leave devoted friends and allies.

Copies of Kino's preliminary 1685 plan went to Bishop Garabito, the Mexican Viceroy, Jesuit Superiors, and friends in Europe, in particular to the Duchess of Aveiro with the plea that she intercede with the highest Spanish officials in behalf of California.

Viceroy Paredes was convinced by Kino's report. He ordered the immediate re-activation of the Lower California enterprise. Missionaries and twenty men were to be taken back to San Bruno.

Kino was overjoyed at the favorable decision. He returned to Matanchel from Guadalajara, ready to join the new California expedition. The flotilla was riding at anchor in the harbor when word arrived to warn the heavily-laden Manila Galleon (en route from the Philippines to Acapulco) of the presence of pirate ships. Kino accompanied Atondo on the "Almiranta" as the fleet sailed out of the harbor on November 29, 1685. They found the Spanish Galleon and convoyed her in safety as far as Acapulco.

From here Kino rode over the high sierras to Mexico City, arriving there in mid-January of 1686, With Viceroy Paredes' promise to revive the California enterprise and the successful rescue of the Manila Galleon, Kino's hopes were at their highest.

A few days later, all his bright dreams of returning to Baja California and his Didius suddenly vanished - dispelled by the urgent order of the Spanish monarch to send immediately to {he Madrid treasury half a million "pesos". No money was now left for the California enterprise. Of course, officials did not say that it was to be abandoned; they used a softer but no less lethal term - it was merely suspended. .... On November 26, 1686, Kino set out for the distant north of New Spain.

Edward J. Burrus

Kino and Manje: Explorers of Sonora and Arizona, 1971

Excerpt from Chapter 2: On To California (1681-1686)

California Departure and Kino Return Prevented by Pirate Threat To Manila Galleon

To download the above account with additional background on Kino plans and vision, click

California Departure, Vision & Pirates - Burrus document (text)

Map of New Spain and Guatemala 1520 - 1775

Left Page of 2 Pages

North America Pacific Coast with Ports and Manila Galleon's Course

Pirates Swan and Townley

November 1685 - April 1686

Pirates on the West Coast of New Spain, 1575-1742

Peter Gerhard

Chapter Excerpt: Preface

|17| For a century only squadrons of war or semi-official expeditions with large financial support were able to invade the South Sea, and at no time were pirates on the west coast anywhere near as numerous as in the Caribbean. Of those who made the attempt some few were fabulously successful, but more returned empty-handed, and many did not return at all. From the Spanish records we get a point of view sharply contrasting with the English and other sources, that of the often defenseless Spanish and mestizo sailors and settlers who came between the pirates and their booty. To the inhabitant of the west coast of New Spain piracy was a scourge which affected him in a very personal way, and he could scarcely be blamed for looking on the pirates as unprincipled thieves and scoundrels to be dealt with harshly when the opportunity was presented.

Chapter Excerpt: The Buchaneers

|164| Swan and Townley, with 340 men in their two ships and two small prizes, decided to cruise northward for the Manila galleon. ...

On November 13 the buccaneers went ashore in force in the estuary of the Ometepec River, and drove off a large body of Spaniards who were waiting behind an improvised breastwork. A foraging party here took a mulatto prisoner who told them about a ship recently arrived at Acapulco, and Townley conceived the ambition to take her as |166| a prize, being dissatisfied with his own vessel. [65] In the evening of November 17, within sight of the Paps of Acapulco, Townley put off with 140 men in twelve canoes, and the following day he landed at Puerto Marqués. During the night of November 19-20 the pirates rowed across to the inner harbor of Acapulco and found the desired prize anchored directly beneath the castle of San Diego. It was clearly impossible to cut the ship out without being blasted by the fort, so Townley contented himself with getting a good view of the town and castle in the early dawn before returning aboard his vessel. [66] The pirates closely followed the shore west of Acapulco, making a raid on the village of Petatlán, passing Zihuatanejo (November 23), and calling at Ixtapa, where they secured some beef and took a mule train with a quantity of provisions. Swan kept as a servant a mulatto boy he captured at Ixtapa.[67]

Meanwhile in Mexico City the viceroy had been informed of the pirates' activities and took steps to defend the Manila galleon. He ordered Admiral Isidro Atondo y Antillon, who had just returned from a pearling expedition to Lower California, to go out in his little "balandra" and escort the ship expected from China. [See Editor Note ** Atondo-Kino Expedition to Lower California]. Atondo sailed from Matanchel on November 25 and crossed in only three |171| days to Cape San Lucas, where the Manila galleon "Santa Rosa" had just arrived, an amazing coincidence. The two vessels crossed the mouth of the gulf, reaching Salagua on December 8, Zihuatanejo on the 18th, and Acapulco on the 20th. [68] How they managed to avoid Swan and Townley, whom they must have passed just south of Salagua, is a mystery. Possibly they slipped by each other during the night of December 9-10. In Mexico the galleon's escape was considered a miracle.

The pirate fleet went in to Salagua on December 11, and the next morning two hundred men landed and routed a "large" war party on the beach. Here they took prisoners who disclosed some helpful information about the countryside, but made no mention of the fact that the Manila ship had been in this same bay just three days before. Clearly the buccaneers lacked a good interrogator. Still sanguine with the thought of capturing this rich prize, they sailed from Salagua on December 16 and strung out their ships for a distance of ten leagues off Cape Corrientes. Four of Townley's canoes were sent in to Valle de Banderas to look for provisions. This landing party skirmished with some Spaniards, losing four men and killing eighteen of the enemy. On December 28 the pirates had to abandon their blockade and run down to Chamela Bay for water and wood, leaving Townley ashore with sixty men to rummage the countryside. The |172| fleet returned northward and entered Valle de Banderas on January 11, 1686. [69] ....

On February 12, eighty pirates landed at the mouth of |173| the Chametla (Baluarte) River and marched to Rosario, where they stole eighty or ninety bushels of maize. Seventy men were sent into Rio Grande de Santiago on the twenty-first, and from a prisoner they heard of the town of Senticpac fifteen miles inland. Swan, still badly in need of supplies for his voyage across the Pacific, went with 140 men in eight canoes up the river and marched overland, taking Senticpac without resistance on February 26. They found a good supply of maize and began to transfer it on horses to the canoes. While they were doing this a large party of Spaniards carried out an ambush and succeeded in killing fifty of the buccaneers, one-fourth of Swan's entire force. The forlorn survivors returned to their canoes and paddled down to the waiting ships. [71]

On March 3 Swan left the mainland and set course for Lower California. However, he was driven back to the Tres Marías Islands, where he spent almost three weeks (March 17-April 5) at the east end of María Magdalena careening his two vessels. They returned to Valle de Banderas to take on water, and on April 10, 1686, the pirate ships cleared Cape Corrientes and began the long voyage across the Pacific. [72] ....

Chapter Excerpt: Conclusion

|241| Piracy on the Pacific side of America never reached the proportions that it assumed in the Caribbean. The difficulties of getting there and returning, and the problems of securing provisions, were often overwhelming. Furthermore, the west coast of Central America and Mexico was not a very profitable cruising ground for pirates or privateers, unless they were fortunate and strong enough to take a silver shipment from Peru, or a Manila galleon. The Pacific coast of South America was somewhat more accessible and had more local shipping and coastal towns with a certain amount of wealth.

Although a cruise on the west coast of New Spain was often an unprofitable venture for pirates, their raids caused the Spaniards a great deal of inconvenience and financial loss. Loot taken away was only a small part of the damage. The value to Spain of the ships sunk, towns burned, agriculture and commerce destroyed and inhibited, and other direct and indirect effects of these raids ascended to many millions of pesos. ....

Perhaps the most permanent effect of piracy on the west coast of Mexico was an indirect one brought about by the reiterated order forbidding or discouraging colonization of the coastal region. The long stretches of deserted seashore, including much fertile territory which still lies unfilled and abandoned, may well be partly the result of this old colonial policy intended to discourage pirate visits.

Peter Gerhard

Pirates on the West Coast of New Spain, 1575-1742

Spain in the West Book Series Volume VIII Book Series, 1960

Chapter Excerpt: Preface

Chapter Excerpt: The Buccaneers

Chapter Excerpt: Conclusion

To view entire book that is available online at HathiTrust to public, click →

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008024526&view=1up&seq=8

To view almost all book online as a Google book sampler, click →

https://books.google.com/books?id=9E37ysm1rkcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

__________________

Notes - Chapter Excerpt: The Buchaneers

[60] Dampier, op. ext., 163.

[61] Robles, "Diario", II, p. 104.

[62] Dampier, op. cit., 163-166.

[63] Robles, op. cit., II, p. 105.

[64] Dampier, op. cit., 166-169

[65] Ibid., 169-170.

[66] Ibid., 170-172.

[67] Ibid., 172-175. Robles, "Diario", II, p. 106, says that news of an enemy off Colima reached Mexico City on November 19. Perhaps the pirates had sent canoes ahead.

[68] Letter from viceroy, March 28, 1686, in "México" 55, AGI.

[69] Dampier, op. cit., 177-181.

[70] lbid., 181-182.

[71] Ibid., 182-189. Basil Ringroie, the chronicler of Sharp's expedition, was one of those killed. Cf. Robles, "Diario", II, p. 116. The latter says Swan had released twenty prisoners before this battle, and the pirates "are perishing of hunger, and eat dogs, cats, and horses."

[72] Dampier, op. cit., 190-194. Swan's crew mutinied in the Philippines and soon afterward Swan was killed. Dampier and others of the crew reached England in another ship.

[73] Letter from viceroy, February 16, 1686, in "México" 55, AGI.

[74] Robles, "Diario", II, pp. 115, 119

Pirates on the West Coast of New Spain, 1575-1742

Peter Gerhard

Chapter Excerpt: Preface

Chapter Excerpt: The Buccaneers - expanded text

Chapter Excerpt: Conclusion

Map of New Spain and Guatemala 1520 - 1775 (left page of 2 pages).

Excellent Glossary at page 245.

Map of "New Spain and Guatemala 1520 - 1775" at pages 27 and 28.

Republished in 2003 with new title of "Pirates of New Spain, 1575-1742".

To download the above account with additional background, click

New Spain Pirates - Gerhard document (text)

Kino Finding The Santa Rosa off Baja California's Cape San Lucas

Painting of the Manila Galleon Nuestra Señora del Pilar-de-Zaragoza

Kino's Ship Meeting Galleon Near Cabo San Lucas - A Miracle in Mexico City?

The viceroy had been informed of the pirates' activities and took steps to defend the Manila galleon. He ordered Admiral Isidro Atondo y Antillon ... [to] escort the ship expected from China. Atondo [with Kino] sailed from Matanchel on November 25 and crossed in only three days to Cape San Lucas, where the Manila galleon "Santa Rosa" had just arrived, an amazing coincidence. The two vessels crossed the mouth of the gulf, reaching ... Acapulco on the 20th. How they managed to avoid [pirates] Swan and Townley, whom they must have passed just south of Salagua, is a mystery. ... In Mexico the galleon's escape was considered a miracle.

Peter Gerhard

"Pirates on the West Coast of New Spain, 1575-1742" 1960

Manila Galleon Pacific Routes

The Galleons Sailed Close Along The California Coast

Record of The Manila Galleon Kino Escorted to Acapulco

Capitana Nao Santa Rosa

AÑO: 1685

BARCO: Capitana Nao Sª Rosa almiranta

SALIDA: 23-jun

LUGAR: M

LLEGADA: 20-dic

OBSERVACIONES: (Cont. 1244) Cajas Reales de Filipinas. 1685: “nao que se despacha a Nueva España: Santa Rosa.” (Cont. 1248) “Galeón Santa Rosa: Salió de Cavite el 23 de junio de 1685” Lo mismo en (Cont. 1249) (Mex-55,R3,N15) Carta del virrey de Nva. España a S.M. sobre...protección a la nao de China. (México, 28-mar-1686): “...salió del puerto de Matanchel el día 25-nov y dio con la nao de China a los 28 de él (nov) en el cabo [San Lucas]. Y la amiranta se levó del mismo puerto el referido día 28 y entró la nao y balandra a los 30 y todas juntas se avistaron a Salagua el día 8-dic y al puerto de Siguatenexo a los 18 echando pliego de su general para mí, y a los 20 de dicho mes surgió en el puerto de Acapulco la dicha nao de Filipinas convoyada de dichos bajeles de la California...” (Cont-906B) “la nao capitana Sª Rosa: El 20-dic-1685 se inicia la descarga.”

TABLA 2. RUTA FILIPINAS – ACAPULCO at page 73

For other Manila Galleon voyages while Kino in the Californias, see "Transcriptions of documentary information relevant to the voyages of the Manila Galleons, from the Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. (Two Tables, in Spanish)

Table 1 (pp. 2-47) is for the voyages from Acapulco to Manila

Table 2 (pp. 48-92) is for the voyages from Manila to Acapulco."

To download, click

Manila Galleon Voyage Transcriptions

Map of Spain's Major Global Sea Routes for Trade and Communication

New Spain's Response To Pirates Swan and Townley

Gilberto Lopez Castillo

"Piratas en el Mar del Sur: El Rosario y Mazatlán:

Estudio de caso en las costas del occidente novohispano, siglo XVII"

(Pirates in the South Sea: El Rosario and Mazatlán:

(Case study on the Coasts of Western New Spain, 17th century.)

Gilberto López Castillo, INAH Sinaloa

María Isabel MarínTello, Facultad de Historia UMSNH

Primeria Parte: "De Las Labradas a Mazatlán. Historia y arqueología.", 2014

75 Aniversario INAH

Kino's Fortification Plan for San Bruno

Protect Town From Indian and Pirate Attack

Editor Note: Summary of Kino in California

The Atondo-Kino Expedition (1683-1685) was funded by the Spanish King which was unique in Spanish colonial history. The King orders for the expedition were three: explore the unknown land the Spanish called the Island of the Californias - now part of the Baja or Lower California peninsula; establish the first permanent settlement and seaport for the Manila galleons; and of paramount importance to the King, convert the Indians to Christianity. Jesuit explorer and cartographer Eusebio Francisco Kino (1665-1711) was Admiral Atondo's ecclesiastical counterpart and the expedition's Royal cosmographer. The expense of supplying the expedition along with the unpredictability of ship transport across the Gulf of California caused the effort to be temporarily abandoned in Fall 1685. The expedition returned to the Mexican mainland to reorganize. Atondo's pearl fishing was a desperate attempt to show the promise of the Californias and the importance of continuing the expedition before Atondo's return. Atondo recovered several miniscule pearls for the King.

In late November 1685, the expedition was ready to sail back again to Baja and restart again. Suddenly pirates were raiding along the west coast of the Mexican mainland which threatened the safety of the Manila galleon and its treasure cargo. The viceroy changed Atondo's orders and directed that he sail to protect the galleon. Atondo with Kino convoyed the galleon to Acapulco. When Atondo and Kino returned overland to Mexico City 2 months later, the funding by the King for the return was no longer available. While waiting for his next assignment, Kino ministered to captured pirates who were imprisoned in Mexico City. He wrote the Duchess of Aveiro in Madrid asking that she petition the King to reduce the prison sentences of the pirates.

The pirate threat to the Manila galleon had ended the Atondo-Kino expedition. But for the next 12 years, Kino lobbied the King for the renewal of the settlement effort. In October 1687, Father Juan María Salvatierra fulfilled Kino's vision. Salvatierra, walking in Kino's footsteps, established the Californias' first permanent settlement at Loreto. This expedition was funded solely by the Jesuit's Pious Fund of the Californias. For remainder of his life, Kino continued to support the Spanish Californias whose existence was always tenuous. While working for the next 2 decades from his missions in Sonora and Arizona, Kino was placed in charge of supplying the Californias from the Mexican mainland.

Editor

María Guadalupe de Lancaster

Duchess of Aveiro, Arcos y Maqueda with Her Children

Mother of the Missions 1692

Kino Asks the Duchess to Petition The King For Reduce Prison Sentences For The Pirates Imprisoned in Mexico City

Kino asks the Duchess of Aveiro, Arcos y Maqueda that she request that King of Spain reduce the prison sentences of 25 English pirates captured along the Pacific coast in the letter set out below. The letter was written on the day Kino left Mexico City to travel 1,500 miles to his new assignment in the Pimeria Alta. Kino ministered to the pirates in prison while he was waiting for eight months in Mexico City to learn of his new assignment.

"P.S. .... I commend to your Excellency the twenty-one Englishmen whom we recently converted here; I refer to this in the hope that there may be some opportunity offered you of securing a mitigation of their prison term which is five years. Do pardon the trouble which my requests may entail."

Your Excellency, the Peace of Our Lord be with you!

Some six months ago, shortly after reaching Mexico City from California (or Carolinas), I wrote <2> to your Excellency giving you an account of that vast Island's extensive mission field so ripe for the harvest of souls, and the heartrending pleadings which those gentle and tractable natives (after their instruction in the tenets of our holy faith) are making to receive holy baptism. <3> I also recounted how we sailed out in the California ships to meet and warn the Manila Galleon about the enemy pirates lurking along the coasts of the South Sea in order to capture it. By God's favor, we succeeded in bringing the Galleon into the port of Acapulco to the chagrin of the four enemy ships. <4>

Afterwards, about the middle of January of this present year of 1686, we continued from Acapulco to Mexico City. In April, as we were on the point of returning to California to get on with the conversion of the many docile natives and gather in so ripe a harvest, a decree arrived from Madrid. Inasmuch as the previous year of 1685 a report had gone out from here to the effect that Nueva Vizcaya, <5> because of the natives' restiveness, was on the brink of ruin, the order came enjoining the assistance to and preservation of that province or territory of Nueva Vizcaya, even if this entailed the suspension of the California enterprise with its settlement and conversion. But as this suspension was effected not because of the peril to which Nueva Vizcaya is exposed (as the royal Attorney-general <6> states in his reply of May 6th of the present year of 1686), additional subsidies instead were obtained for four new missions: <7> two among the Tarahumaras and the others among the pagan Seri and Guayma Indians who live within sight of California, so close that only fifteen or sixteen leagues separate them. My superiors recently appointed me to found this new mission or missions among the Seris and Guaymas, who are also pleading for holy baptism. For this purpose I shall be departing, God willing, from Mexico City in just two days. <8>

Although we are hoping that the final decision for the continuing of the settlement and conversion of California (or Carolinas) will be a favorable one, and are consoled by the news that the next Viceroy <9> is well disposed towards the missions through his devotion to the eminent apostle and angelic Saint Francis Xavier, and, further, are reassured by the grant of two subsidies for the two new missions among the Seris and Guaymas with the observation that the sum would thus help promote the continuity of the conversion of nearby California; despite all this, the uncertainty of the future is blocking or delaying the dispatch of the spiritual assistance for the salvation of so many souls so eager to receive holy baptism. <10> In all sincerity and from the depth of my heart, as also in the name of those gentle and tractable natives, I commend, not once but a thousand times, this enterprise to the holy zeal of your Excellency so that, when the occasion presents itself and you judge it opportune, you will deign to favor so holy a cause. To this end it would help to keep in mind the following three points. <11>

The first is that at present it is possible to secure the continuation of the settlement and conversion of California with a moderate and wisely employed sum from the royal treasury, <12> whereas since 1680 nearly half a million pesos have been spent <13> (that is, approximately one hundred thousand pesos each year), and the earlier expeditions <14> entailed an outlay of two million more, namely those of Hernan Cortés in 1523, of Sebastian Vizcaino in 1597 and 1602, of Francisco Ortega in 1634, of Admiral Pedro Porter Casanate in 1644, of Bernardo Bernal de Piñadero in 1677 and other attempts involving large ships and "long boards," armed soldiers and marines, weapons, supplies and repairs; the expenditures for the discovery and settlement of California amounted to the sums stated above. But now with a couple of long boats and a small garrison of twenty or twenty-five soldiers and four to six missionaries (a total expenditure of some twenty thousand pesos and, if necessary, of even a smaller outlay), it is possible to effect the desired project of the peaceful settlement of California, as can testify many level-headed men with experience gathered during the last few years through their participation in the California enterprise.

Everyone knows how much the undertaking has suffered and has been retarded and how much useless expenditure has been incurred by employing large ships and sailing them over a route more than two hundred leagues from Compostela and Guadalajara in order to transport the provisions to California, with a delay of usually nine or ten months until the bulky shipment finally arrived and half rotten at that; whereas with a weekly crossing of long boats from Sinaloa and Yaqui, it would be easy to secure all that one might desire.