Speaking Truth To Power

Kino - Jesuit Exemplar

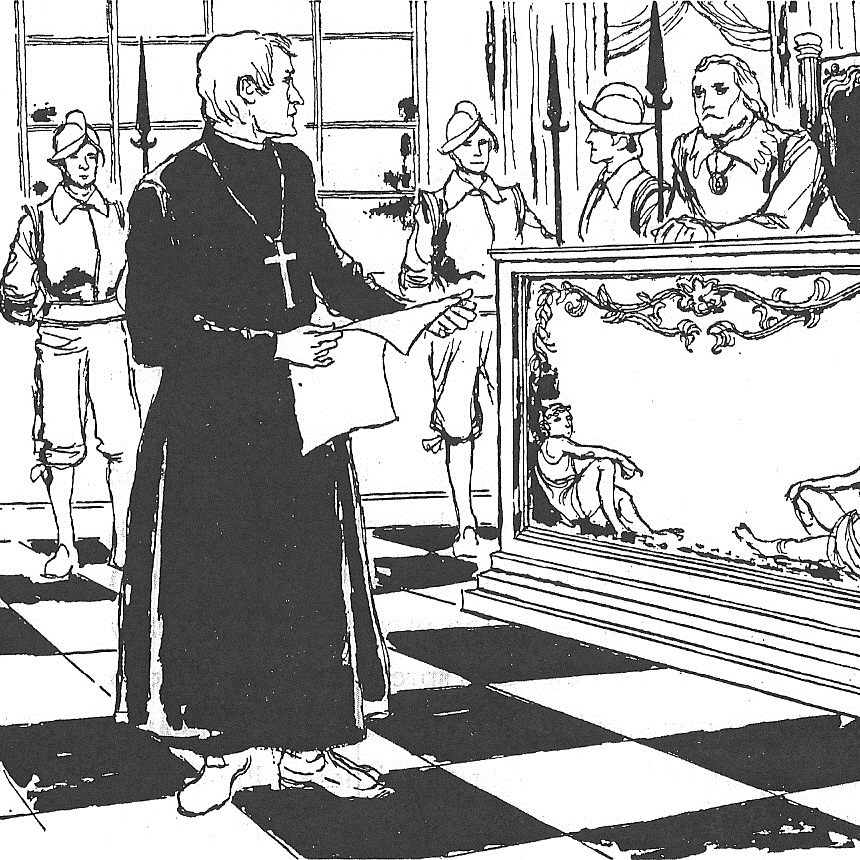

Kino Presenting His "Biography of Father Saeta"

Before The Viceroy In His 1696 Defense of The O'odham People

Jesuits in New Spain

Harry W. Crosby

The conversion of native Americans, both to the Catholic faith and to a settled Hispanic way of life, was basic to the colonial plan. Explorers and conquerors on the west coast frontier of New Spain were accompanied by Franciscan missionaries and other clerics, all of whom had difficulty in converting the indigenous people. In 1591, the crown awarded the religious responsibilities to the Society of Jesus, a new, vigorously evangelical order.

The Jesuits had arrived in the New World a half a century after the conquest began. Their first evangelical efforts in the North America were impractical and short lived attempts between 1566 and 1572, to settle and preach among Indians around Chesapeake Bay and in Florida. With idealistic fervor, they undertook the ventures without protections of soldiers and paid the price by the loss of ten or more of their members. Meanwhile, plans were afoot to send Jesuits to New Spain, and they first arrived in 1572. By then, the populous regions with highly organized societies had been relegated to other missionary orders for conversion to Christianity and Europeanized village life. The Society of Jesus turned to available tasks, created a school system, and soon offered New Spain's foremost teachers and operated its best and most prestigious colleges. This function brought the order into close contact with the colonial elite class. However, the Jesuits soon became involved in the crown's renewed interest in adding lands and peoples to the holding of Spain. The strongly-backed Royal Orders for New Discoveries of 1573 placed missionaries in the forefront of forces directed to find, occupy, and evangelize new lands. The active Jesuits made themselves available and, as noted, in 1591 accepted the challenge of New Spain's remote and inhospitable northwest frontier. |9|

By the late sixteenth-century, the Society of Jesus was well established on the coastal plain that forms the eastern shore of the Gulf of California, then called the Mar de Cortés of the Mar Bermejo (Sea of Cortés or the Vermillion Sea). |10| Before a century had passed, Jesuits had created a series of missions in Sinaloa and Sonora that gathered thousands of converts. These neophytes learned not only the rudiments of Christianity but also the skills to propagate thriving agriculture and large herds of domestic animals, particularly cattle. |11| However, the Spanish government's ideal plan - which asked the military and the religious to perform different roles and to share power - seldom worked harmoniously. Missions occupied land and sequestered convert laborers. These same assets were coveted by local ranchers and miners, some of whom were soldiers as well. |12| Conflicts over authority and economic advantage were common in New Spain, but they reached unusual heights of acrimony in Sinaloa and Sonora, a circumstance that was to color the history of nearby California. |13|

Jesuits came to the New World at a perfect time to infuse new life into a flagging system. The Society of Jesus had not been present during the conquest [6] periods, it arrived late and had its greatest growth at exactly the time when populations, economies, and the zeal and morale of other religious orders were declining. Moreover, the mendicant order, of which the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians were conspicuous in New Spain, were creations of medieval impulses; their philosophies and their organizations were old. The Society of Jesus, founded in 1540, was an outgrowth of Spain's crusading zeal and the Counter Reformation, an age as secular and commercial as the former had been religious. |14|

The founder of the order was Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Spaniard and former military man, who conceived an efficient and in many ways modern organization. Jesuits knew their chain of command and obeyed the order that emanated from it. One "padre general" |15| ruled them from Rome; a "padre provincial headed each major geographical area in which the Society was represented. Within the walls of the order, members communicated with relative freedom and honesty. Rules covered most aspects of life, especially procedures by which the Society operated. Most observers of those or later times agree that Jesuits more scrupulously obeyed their rules than members of other orders. All this constructive discipline gave Jesuits a sense of calm and security. They could take pride in the honor and respect accorded their organization. They could feel usefully and honorably employed. They were relieve of many individual responsibilities. They did not have to deal personally with the many levels of government or compete economically for a livelihood.

The society was popular with young intellectuals all over the Catholic world. It drew on men of many nationalities, gave them excellent higher educations, and deployed them wherever the order needed them. This open policy contrasted with that of other religious orders that operated in Spain's possessions - most limited their local membership to Spaniards or their descendants. From its broader base, the Society found outstanding men; morale was very high; dedication and achievements reached levels that would have attracted attention in any time or place. All of this contrasted sharply with the slower and less-directed pace of other aspects of colonial life, encumbered with inefficient traditions and a government characterized by divided authority and endless bureaucracy.

Jesuit achievements worldwide attracted the attention of prominent people. Jesuit morality was viewed as superior. Jesuits conducted their internal affairs so privately that the public had little sense of discord. Despite being closely watched, the Jesuits inspired deepening awe and admiration. The Society's growing domination of higher education increased its advantages. Its students, the children of the influential and wealthy, appreciated their educations and, as they matured, rewarded their mentors with political favors and financial endowments. The Jesuits in turn cultivated those who favored them; they saw to it that their benefactors received public recognition from men at the top of their order and from the crown itself. In a country characterized by complex, overlapping jurisdictions in civil and religious affairs, the cohesive network of the Jesuits and their supporters generated substantial power to further the work [7] of the order. Hasburg rulers of Spain favored the Jesuits because they made themselves available, volunteered for difficult duties and achieved results. At all levels of the royal bureaucracy, officials turned to them for advice and assistance. Jesuits inspired confidence.

Not surprisingly, Jesuit success and influence provoked distrust and envy in many quarters. Other religious orders were jealous of the patronage and perquisites that Jesuits seemed to have reaped at the former's expense. The secular church - the local cathedral and parish clergy under regional bishops resented sharing religious authority and duties with missionaries as well as foregoing income from lands and peoples that comprised missions. Parish priests tended to be New World born; they and many nationalistic Spaniards resented the foreign religious brought in by the Society of Jesus. When the Jesuits invested their money wisely in land and animals - and ran their businesses with unusual efficiency - economic and religious rivals became bitter and made a common cause of anti-Jesuit muttering. Jesuit accomplishments were attributed to every sort of scheming, consorting and covenanting that jealous minds of competitors could devise. |16|

In seventeenth-century New Spain, no religious organization was as prestigious as the Society of Jesus or had the ear of more powerful people. Nevertheless, the corresponding increase in detractors and enemies helped to create a climate of opinion that resulted in the order's expulsion from the entire Spanish world that took place in 1767 .... [8]

Harry W. Crosby

"The Road to California" - Chapter 1 excerpts

"Antigua California:

Mission and Colony on the Peninsular Frontier, 1697-1768"

The Distinctiveness Of The Society Of Jesus

John W. O’Malley

It is in essence a portrait of the ideal [superior] general and is consequently a portrait of the ideal Jesuit. The person, for instance, should be united with God in prayer, a person of sterling virtue, a person who knows “how to combine rectitude and, when necessary, severity with kindness and gentleness.”

Qualities like these are of course necessary and basic but certainly not surprising. They are no more than what we would expect. But the text goes on, in an unexpected way, to describe another quality, unique, as far as I have been able to determine, in the annals of any religious order. That quality is magnanimity.

"Magnanimity and fortitude of soul are likewise highly necessary for him to bear the weaknesses of many, to initiate great undertakings in the service of God our Lord, and to persevere in them with constancy when it is called for, without losing courage in the face of contradictions, even from persons of high rank and power, and without allowing himself to be moved by their entreaties or threats from what reason and the divine service require. He should be superior to all eventualities, without letting himself be exalted by those that succeed or depressed by those that go poorly, being altogether ready to receive death, if necessary, for the good of the Society in the service of Jesus Christ, our God and Lord."

John W. O’Malley

The Distinctiveness Of The Society Of Jesus

Journal Of Jesuit Studies 3, 2016

To download the entire article in pdf format,

Click

https://brill.com/view/journals/jjs/3/1/article-p1_1.xml

The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything:

A Spirituality for Real Life

By James Martin, S.J.

The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life

James Martin

Although primarily a spiritual guidebook written for the layperson by Father James Martin, S.J., "The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life" gives best insight into the thinking, training and work of Padre Kino and his fellow members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). Written in simple clear language, the guide shows in an ethical and practical way how to manage relationships, work, prayer and decision-making while keeping a sense of humor. Used as examples are inspiring and sometimes humorous stories about heroic Jesuits, past and present.

Father Martin summarizes the Jesuit way:: "So if anyone asks you to define Ignatian {Jesuit] spirituality in a few words, you could say that it is: finding God in all things; becoming a contemplative in action; looking at the world in an incarnational way; seeking freedom and detachment."

Father Martin graduated from the Wharton School of Business and worked for General Electric before becoming a Jesuit priest. He is the culture editor of the Jesuit's America magazine and is a frequent commentator on faith and values in a various types of media.

Map of Kino's Europe

Kino's Jesuit Formation Stages

Kino as a Jesuit scholastic (Jesuit priest candidate) completed a series of formation stages that spanned more than a decade before he was ordained as a priest.

These stages also give an account of Kino’s first half of his life as a student and professor at the best universities in Europe.

Novitiate

Landsberg University

1665 - 1667

After attending Hall as scholarship pre-college student and later as a college student at Freiburg, Kino is accepted into the 2 year novitiate and lives in community with Jesuits while ministering to poor. He takes first vows of poverty, chastity and obedience

First Studies

Ingolstadt University

1667 – 1670

Completes 3 year study in philosophy and theology (Bachelor degree) while following Jesuit rules and methods. Continues to minister to the poor. Kino also studies mathematics, astronomy, cartography and other sciences with Ingolstadt's renowned faculty.

Regency

Hall College

1670 - 1673

Fully involved in the life of Jesuit community, Kino returns to Hall and teaches literature. He writes first letters to Superior General requesting to be missionary to China. Kino is inspired by famous Jesuit missionary to China, his deceased cousin Martin Martini

Theological Studies

Ingolstadt University

1674 - 1677

Completes 3 year study in theology (Masters degree) while continuing scientific studies and teaching mathematics. He turns down post as science professor. Kino ordained as priest in June 1677.

Tertianship

Freiburg / Oettingen

1677 - 1678

Receives equivalent of PhD in astronomy and natural sciences from Freiburg University and then Kino ministers full time in parish in Oettingen. Last of his six requests to be missionary is granted.

Final Vow

Baja California

1684

While waiting 2 years for a ship to Mexico, he ministers & teaches in Spain. At age 39 in Baja California on the Feast Day of the Assumption of Mary, he makes before a fellow Jesuit missionary his final Jesuit vow of obedience to Pope's if ordered to serve in miissions. Kino re-affirms his first 3 vows (poverty, chastity & obedience) that he made in Germany when he entered the Jesuit order at age 18 and when he was ordaind a priest at age 32. Suscipe

For more about Kino's life in Europe and entry into the Society of Jesus, click

Europe's Son Page

Jesuit Formation and Lingo

James Martin

"Jesuit Formation and Lingo"

James Martin, S.J.

America: The Jesuit Review

August 11, 2013

Click

https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2013/08/11/novice-regent-scholastic-guide-jesuit-formation-and-lingo

Fr. James Martin describes the stages in the formation or training of the priests and brothers of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) from its beginning to the final vows. The stages can take from 15 to 20 years to complete.

Thinking Like A Jesuit

Malcolm Gladwell

AMDG Interview

Malcolm Gladwell

"Thinking Like A Jesuit"

For Gladwell's Interview on AMDG: A Jesuit Podcast, click

https://soundcloud.com/jesuitconference/malcolm-gladwell-on-thinking-like-a-jesuit?fbclid=IwAR2U4O6DQRcxcV1amqegwkGhfM4fnRXIZ6YiC_J4Ip4HwqRgbyxVCoyZDWhttps://soundcloud.com/jesuitconference/malcolm-gladwell-on-thinking-like-a-jesuit?fbclid=IwAR2U4O6DQRcxcV1amqegwkGhfM4fnRXIZ6YiC_J4Ip4HwqRgbyxVCoyZDW44

Malcolm Gladwell's 3 Podcasts on "Thinking Like A Jesuit" may help solve today's problems & political divisiveness. Also they may give insight into Kino's missiology of tolerance, respect and love.

Critical social thinker and best-selling author and New Yorker magazine columnist Malcom Gladwell in an AMDG podcast interview discusses the relevance of the moral reasoning method that Jesuit founder St. Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556) taught in the 16th century and continues to be used today by Jesuits like Pope Francis.

In the AMDG Interview Galdwell discusses how Jesuits examine difficult problems on a case by case basis by analyzing specific facts & eliminating preconceptions & bias [time mark: 7:00 to 9:30]. Listening is most important together with offering consolation to the suffering [time mark: 13:30 to 16:00].

The 3 "Thinking Like A Jesuit" podcasts on three of today's issues are on Gladwells' "Revisionist History" podcast site.

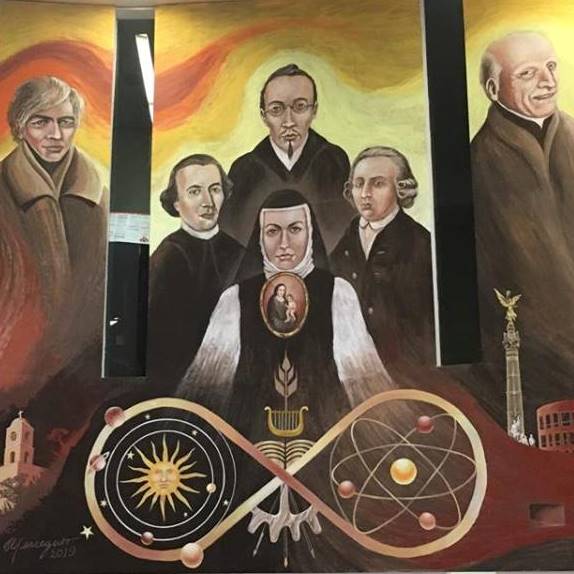

Biblioteca Francisco Xavier Clavigero Mural

Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico City

Kino, Clavigero, Sor Juana Ines, Sigüenza y Góngora, Alegre & Arrupe

Biblioteca Francisco Xavier Clavigero

Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico City.

Part of Library's Mural dedicated in 2019

People depicted in mural from left to right: above mission chuch is Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645-1711), pioneer missionary, protector of the Indians and visionary for the Californias; Francisco Xavier Clavigero Saverio (1731-1787), Mexico's first national historian who died in exile in Italy after Jesuit Expulsion; Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695) "The Tenth Muse" ; Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), New Spain's polymath; Francisco Xavier Alegre (1729-1788), famed 18th century scholar, translator and historian of colonial Mexico who died in exile in Italy after Jesuit Expulsion; Pedro Arrupe (1907-1991) 28th Jesuit Superior General for 18 years. Leader of global social justice and the Jesuit preferential option for the poor, He lived in Hiroshima suburb. After the World War II atomic bomb attack, he provided medical treatment to survivors. More about Arrupe's life at

https://www.ignatianspirituality.com/ignatian-voices/20th-century-ignatian-voices/pedro-arrupe-sj/

Jesuit Tradition of Scientific Inquiry

A remarkable characteristic of the Society of Jesus during the period of its first founding (1540-1773) was the involvement of its members in the sciences.

The reasons for this interest in scientific study can be found in the nature and mission of the order itself. Saint Ignatius Loyola considered the acquisition of knowledge and the performance of mundane labor as spiritually profitable tasks, and this fostered in the Society an action-oriented, utilitarian mentality sympathetic to scientific study. In addition the role of the Society as the "schoolmasters of Europe" meant that the pedagogically (and scientifically) useful principles of rationality, method, and efficiency were highly valued.

The tight-knit organization of the Society created among its members habits of cooperation and communication, essential for the gathering and exchange of scientific information. Finally, mission work in Asia and the Americas gave the Jesuits opportunities and impetus to study and record the phenomena of these new worlds.

Jesuits and the Sciences 1540 - 1999

Loyola University Chicago

Digital Special Collections - Exhibits

http://www.lib.luc.edu/specialcollections/exhibits

"Jesuits As Science Missionaries"

For background on the Jesuit scientific tradition from the Jesuit's beginnings to the present, click

https://theconversation.com/jesuits-as-science-missionaries-for-the-catholic-church-47829

Science 2.0

September 27, 2015

Accessed:November 27, 2015

Eusebio Francisco Kino - Jesuit Exemplar

Biblioteca Eusebio F. Kino Del Instituto Libre De Filosofía Y Ciencias

Provincia Mexicana de la Compañía de Jesús

Mexico City

Biblioteca Eusebio F. Kino del Instituto Libre De Filosofía Y Ciencias

The Biblioteca Eusebio F. Kino (Kino Library) is the archive of the Jesuit Province of Mexico. The archive contains manuscripts and maps, mostly between the 15th and 19th centuries. The collection includes Jesuit reports, correspondence and biographies together with indigenous vocabularies, royal decrees and other viceregal doucments. The archive is a source of primary historical materials that give insight into the daily life of the New Spain. The Kino Library is a member of AMABPAC, an organization of private libraries in Mexico.

Biblioteca Eusebio F. Kino

del Instituto Libre De Filosofía Y Ciencias

Provincia Mexicana de la Compañía de Jesús

Matamoros 75, Col. El Carmen, Alcaldía Coyoacán, C.P. 04100, CDMX

Telephone 55 5659 3097

The Teaching of The Jesuit Missionary

Charles W. Polzer

In working on the history of the Society of Jesus and especially its early missions, I have learned that its missionaries were not preoccupied with questions of orthodoxy and refinements of the Magisterium. They were much more radical; they were really doing what Christ asked us to do - that is, to teach the Way, to teach Christian living. They were not worried about making certain that their neophytes were doctrinally precise. As a matter of fact most converts had no clue about what they were being taught-at least in the beginning.

These observations compel one to become critical about what the mission of a missionary is, what the mission of the Church is, what the mission that Christ has given is - to those who were to follow Him and teach as He did. When I look at the life of Padre Kino and the other missionaries with him, this is precisely what I see. This may be a misreading, a misinterpretation, but I do not think so. When Christ said, "Go and teach all nations," we were thrust on a course of contacting peoples that would seek in some way to transform them. But the question is, what do you transform? Are people to be transformed according to what they think? Or how they act? Or perhaps both? What is the interaction to be expected? We can even more basically ask: what is the goal of mission? What is the final causality? Sometimes a nominalistic answer is offered: "Well, one converts them from being pagan to being Christian, to being believers in Christ, obviously." But how do you know there has been conversion? Here we find ourselves confronted with the same question that Saint John asked: how do you know they are Christians? And he answered better than anyone, ever-better than Bishops, councils, congregations, or encyclicals. "You shall know them by their love." For Saint John, it was not a question of what they thought; it was a question of what they did. It was a question of interpersonal conduct. It was a question of outreach in a sense of giving, in a sense of community, in a sense of sharing. In fact, in the earliest days of the Church, its members were not known as "Christians," but as "Followers of the Way." They were doers, although we can presume they were not exactly inept at theology either.

If this is historically accurate, then a mission really attempts to reach out to others and asks for "metanoia," a change of life; this clearly becomes the goal and option of our contact. Our educational efforts, then, focus on bringing this change about, and we naturally attempt to shore our efforts up with rational argument and example. Put yourselves in the shoes, boots perhaps, of a man like Padre Kino, who was young, vital, and a dreamer of almost impossible dreams, somewhat like Don Quixote-well, not exactly, because Kino came from the Italian Tyrol and not La Mancha. Imagine yourself, like Kino, being sent to the New World to contact people whose language you do not speak. He was contacting people who did not understand his language either. How do you educate? How do you communicate? What can you do under these circumstances to change their lives? How can you preach or teach "metanoia"? This is not an easy task, but this is what the foreign missionary faced. He came without tools to communicate and was expected to construct those very tools. Arriving in a totally foreign culture, bereft of the means of communication, he was expected to transform native peoples from being pagans to being Christians. He was to build Christian community among peoples whose concept of God bore little resemblance to the Hellenic biases of Christian dogma. This was no mean feat. But this is exactly what a man like Padre Kino set out to accomplish. So when we look at the problematic situation that faced Jesuit missions world-wide, we can only be amazed at their foolhardy faith-and even more at God's graceous generosity.

In my own historical work I have seldom concentrated on the Jesuit missions of the Orient; I have spent my time studying missions in the New World - the Western hemisphere - particularly North America. One of the elements that has caught my attention is the enormous discrepancy between the cultural 'presuppositions of Western culture and those of the Americas. One sees that the Western mind has considered itself far advanced over these "primitive, savage, backward, unenlightened, and dull peoples." But when one pays honest attention to Indian cultures, none of these judgments rings true. Perhaps the cultures of the Americas did not display the kinds of scientific sophistication with which we credit ourselves, but the Indians' knowledge and integration of nature with their way of life, with their sense of morality, were remarkable. As a matter of fact, it is only today that the West is coming to understand the immense sacredness of nature that cries for respect, a respect that long since characterized Indian cultures in the New World - which many Christians deigned to call paganism. …..

What is it that the missionary must teach? What are the basics? Are they the rudiments of doctrine? Are they the ABCs of the Magisterium? Are these the propositions of the Faith? Is this a question of knowledge or something more? I suggest the issue is a holistic one and that the task of the missionary was not, and is not, that of communicating knowledge alone. The missionary's task is one of sharing knowledge, the basic appraisal of nature, and the fundamental appreciation of peoples, their interaction, and their relationships. After all, I must recognize, no matter who I am, what culture I represent, what skin color I have, what bone structure I have, that that "other" out there is a person like me. If that is not seen or accepted, we are locked into a racism of the most destructive kind. The missionary was someone who reached out to the Indian peoples as persons; he tried to move them to discover a better vision of themselves. Often the missionary learned as much from the Indian with whom he worked as he taught them. There is a beauty and wisdom that exists among communities of people that has to be respected. Sometimes we, as communities of people, no matter what may be our origins, can concoct systems that are unjust and unwise. It is then that we must sit down among ourselves to interact and reconcile our aberrations so that we can devise something more beneficial to all. To impose law, morality, and authority on another community solely from the outside is pious folly. Such a process does not create, invite, or engender "metanoia" in anyone. "Metanoia" is an interchange, a complete transformation of the person. When we look at the teachings of the Church, when we review the paradigms of doctrine, they are only valid as metaphors that reinforce, that communicate some richer, higher notion to people who are on a quest for truth, understanding, and ultimately love. …..

That is the faith we find in Padre Kino. This is why I titled this essay, "Kino: On People and Places." I could have recounted his expeditions, his mapmaking, his church-building, with an impressive array of historical statistics. One might then have misunderstood in thinking he came to do these things. No, Kino came to all these places and recorded them because of people. And in finding people in the places he visited and explored and in doing the brave things he did, he found God. He found God in the people he served, and together they joined in the quest of the recreation of the world, which we like to call salvation. We are engaged in something more than just saving our souls; we are engaged in making a newer world, a better world. And we are just barely set out on that path, even though Kino rode those trails more than three centuries ago.

Dr. Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

"Kino: On People and Places"

In "The Jesuit Tradition in Education and Missions: A 450 Year Perspective" 1993

Peter Horwath

Padre Carolus di Spinola, sacerdote jesuita (1564-1622): el primer modelo de vida del padre Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645 -1711)

Father Carolus di Spinola was an inspiration and a Jesuit exemplar to Venerable Eusebio Francisco Kino. For 20 years Spinola ministered in Japan and suffered a martyr's death there. In 1680 Kino wrote to the "mother of the missions" the Duchess of Aveiro "... from my earliest youth and especially after reading the life and martyrdom of our Father in Christ, Carolus Spinola, I have been consumed with great eagerness to the go the East Indies ... " Kino's future assignment in North America was determined by the drawing of straws between him and a fellow Trentino Jesuit for the assignment in Asia. Dr. Horwath provides insight into the relationship between Kino and his role model Spinola. The article appear in Nóesis, Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, vol. 25, núm. 49, pp. 226-244, 2016 Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez.

To view and download in various formats Dr. Horwath's article, "Padre Carolus di Spinola, sacerdote jesuita (1564-1622): el primer modelo de vida del padre Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645 -1711)", click →

https://erevistas.uacj.mx/ojs/index.php/noesis/article/view/722

For additional information about

Kino - The Scientist, click

Cartographer Page

Farmer Rancher Page

Horseman Page

Kino Wheat Page

Missionary Page

as Doctor and Pharmacist

Diccionario Bio-Bibliográfico de la Compañía de Jesús en México

(Biographical Dictionary of the Jesuits of Mexico)

Francisco Zambrano, S. J.

José Gutiérrez Casillas, S. J

Spanish

Click

Read online or download all volumes in pdf format. Volume links are on two web pages.

This monumental work consisting of 16 volumes was published between 1962 and 1977.

Online at Theological Commons - a digital collection of the Princeton Theological Seminary.

16th Century: (1566-1600) Volumes 01 - 02

17th Century: (1600-1699) Volumes 03 - 14

18th Century: (1700-1767) Volumes 15 - 16

Jesuit Historiography Online

Jesuit Historiography Online

Click

http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/browse/jesuit-historiography-online

Jesuit Historiography Online (JHO) is an Open Access resource offering over seventy historiographical essays written by experts in their field.

Aimed at scholars of Jesuit history and at those in all overlapping areas, the essays in JHO provide summaries of key texts from the earlier literature, painstaking surveys of more recent work, and digests of archival and online resources.

JHO is available in Open Access thanks to generous support from the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies at Boston College.

Online The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the Jesuits

To view Google book sample copy online

Click,

In left column type, "Kino" in search box and click Go button.

"Portugal and Spain did not command sufficient resources in personnel …. The share of missionaries working among the indigenous population was above average among central Europeans by comparison with Spanish. Of significance was Eusebio Kino in Mexico, Martin Dobrizhoffer (1718-91), Florian Paucke (1719-79), Anton Sepp (1655-1733) in Paraguay, as well as architect and musician Martin Schmid (1694-1772) in Bolivia."

German-Speaking Lands Entry

German-Speaking Jesuits in the Overseas Missions

Paul Oberholzer, S.J (entry author)

James Corkery, S.J. (English translator)

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the Jesuits 2017

Notes: Other Kino Entries in the Encyclopedia of the Jesuits: Kino, Eusebio, S.J.; Baja California (Antigua California, California); Mexico (Viceroyalty of New Spain); United States of America. The Kino Border Initiative, an apostolate for migrants, is referred to under the entry - Mexico, Nineteenth Century to the Present.

Jesuit Missionary World View

Daniel T. Reff

Critical Introduction: The Historia and Jesuit Discourse

History of the Triumphs of Our Holy Faith ...

English Translation, 1999

Historia de los Triunfos de Nuestra Santa Fe

Andrés Pérez de Ribas, S.J., 1645

For Google preview

Click

https://books.google.com/books/about/History_of_the_Triumphs_of_Our_Holy_Fait.html?id=iv4BAIMoxkoC"

Critical Introduction Section Headings: Jesuit World View

Contextualizing Missionary Discourse

The Theological and Ideological Context of Jesuit Missionary Discourse

Literary and Rhetorical Contingency

The Political and Institutional Context of Jesuit Discourse

Jesuit Images of the Indians and the Process of Conversion

The Dynamics of Jesuit-Indian Relations

Conclusion

The Jesuit Expulsion - 1767

Motín de Esquilache

Francisco de Goya

1766 Madrid Bread Riots

Planned Suppression of Kino and Other Jesuit Missionaries, 1710

Herbert E. Bolton

To Kino's letter of September 16, 1709, the procurator replied with shocking news. Father Eusebio might not need the requested missionaries or the new bells! The bishop of Durango was demanding that all the missions of the Society in New Spain be suppressed. [1] What was worse, it was reported that the king had yielded to the demand. |583|

Moreover, the Father General had obediently ordered the Provincial, "that as soon as . . . he is informed of the suppression or that the king desires the alms, . . . at once all the missionary fathers of the Province shall retire and be placed in the colleges." How then, "can your Reverence expect to obtain what you request?" Indeed, how could he?

This ominous letter was written in Mexico on February 1, 1710. [2] Kino died at Magdalena thirteen months later. It is perhaps too much to hope that the mails were so slow that he did not receive it, and therefore never learned the distressing news. ... |584|

Herbert E. Bolton

"Still in the Saddle"

Excerpt from Chapter 150

"Rim of Christendom:

A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino: Pacific Coast Pioneer"

Footnotes

[1] Kino to Juan de Yturberoaga, Dolores, December 7, 1709. Original Spanish manuscript in the Stevens Collection.

[2] Yturberoaga to Kino, Mexico, Feb. 1, 1710. Draft of reply to Kino's letter of Sept. 16, 1709, written on the back. Original Spanish manuscript in the Steven Collection. The threatened suppression did not take place at this time.

Editor Note: Father Juan de Yturberoaga was the procurador of the Jesuit province of New Spain and from his Mexico City office was in charge of the centralized purchase and distribution of supplies to the missions throughout the province. The planned suppression of Kino and other Jesuit missionaries did not take place at this time.

Surviving New World Jesuits Transported To Europe Under Arrest

One Hundred and One of 688 Jesuits Died During the New Spain Expulsion

Twenty-nine Jesuits were killed by Native Americans - for religious reasons or in insurrections - during the 201 years that the Jesuits were in Mexico. Their work ended in 1767, before the founding of the United States, when the Spanish king expelled them from all Spanish lands. During the expulsion from New Spain to Europe, 101 of the 688 Jesuits in the New Spain died from maltreatment and disease.

John J. Martinez, S.J.

Introduction page viii

Not Counting the Cost: Jesuit Missionaries in Colonial Mexico - A Story of Struggle, Commitment, and Sacrifice 2001

The Expulsion of the Jesuits from New Spain, 1767

Peter M. Dunne

Main Article

.... Robert Southey, writing of the Jesuits of Brazil, says: "Centuries will not repair the evil done by their expulsion. They had been the protectors of a persecuted race, the advocates of mercy, the founders of civilization; and their patience under unmerited sufferings forms not the least honorable part of their character." ...

The Jesuits were expelled from Portugal and its colonies in 1759. Then came France, where in 1762 the weak Louis XV was prevailed upon ... The decree was not executed in the colonies until the following year.The blow fell in Spain in 1767. King Carlos III, naturally friendly and with a background of long cordial relationship with the Society, was duped by his Voltairean minister, the Conde de Aranda, and others into thinking the Jesuits were plotting against his throne and he ordered their expulsion from his kingdom and from all his colonies. ... Six years after the expulsion from Spain, Pope Clement XIV, under threat of schism on the part of these courts, signed the decree for the general suppression of the whole Society.

As far as Spain itself was concerned things were arranged with summary finality for a complete expulsion within a single day, for on the night of April 2 and 3 all the Jesuit houses were surrounded and every single Jesuit placed under arrest.

In the colonies the time for the execution of the decree differ..... In Nueva España, that is, in the provinces of Mexico, the hour stated for the exodus from the capital and its environs, differed from that of the missionary country north and west. In Mexico City the fatal day was June 25.

The Expulsion From Mexico City

The explosion of the bomb is fitly described by Bancroft. "Early in the evening of the 24th of June 1767, the Viceroy, Marques de Croix, received in the palace the "audiencia," the Archbishop of Mexico, and the rest of the high officials, whom he had summoned to a meeting for a consideration of an important and confidential affair of state. Croix then produced a sealed package which he had received from the supreme government. Upon removing the outer envelope there was found another, upon which was written the following words: "pena de la vida, no abrireis esta pliego basta el 24 de Junio á la caida de la tarde.' ...

On removing the last wrapper the full order was found expressed in the following terms: "I invest you with my whole authority and royal power that you shall forthwith repair with an armed force ('a mano armada') to the house of the Jesuits. You will seize the persons of all of them, and despatch them within twenty-four hours as prisoners to the port of Vera Cruz, where they will be embarked on vessels provided for that purpose. At the very moment of each arrest you will cause to be sealed the records of said houses, and the papers of said persons, without allowing them to remove anything but their prayerbooks, and such garments as are absolutely needed for the journey. If after the embarkation there should be found in that district single Jesuit, even if ill or dying, you shall suffer the penalty of death. 'Yo e1 Rey'."

The "Visitador General," José de Gálvez, took charge of the details of the expulsion from Mexico City. He laid well and speedily his plans, trying to foresee and to foretell every possible emergency or difficulty. At eleven o'clock that night of the twenty-fourth, after the city had gone to sleep and the fathers were slumbering without a hint of suspicion, three thousand soldiers, foot and horse, were ordered out to surround each of the religious houses of the capital. There were thirty communities of men and twenty of women. Each received a guard of thirty or more men. But the five Jesuit houses were entirely surrounded by a strong guard and all the approaches covered.

Likewise, for fear of tumult, the palace of the Viceroy was protected with a guard while forty field pieces covered the approaches. The orders were that at the stroke of four, the morning of June 25, the door-bell of each Jesuit house should be rung, the community got out of bed and placed under arrest, and an inventory taken of all goods, monies and treasures, supposedly owned by the fathers. ....

A search for the supposed treasure of the rich Jesuits was now instituted. There was treasure indeed, but to the surprise of the officials it was treasure owed. The house was 40,000 pesos in debt and just 80 pesos were at hand for the running expenses of the community. ...

Similar scenes were enacted in the other Jesuit houses of the capital and in the provinces, in number twenty-four colleges and five residences. [21] On this same June morning, or shortly after, the Jesuits of these communities were all imprisoned in their own houses and guarded until they could be hurried off to Vera Cruz to take ship for Spain and then for Italy, for Carlos III would not allow these men to rest upon their native soil. ....

When the people of the capital awoke that morning they felt a strange silence brooding over the city. Because the religious houses had all been surrounded and their priests forbidden to say Mass, no bells were rung over the city and no services held in most of the churches and chapels. Besides, the people were astonished to find the streets filled with soldiers. ... . A riot was prevented through the dispersal of the throng by the soldiers, and a partial remedy applied by putting other priests to work. [22] No one was to speak with the Jesuits under pain of death ...

The Expulsion from Chihuahua and Tarahumara

Hitherto we have said no word of the missionaries of the north and west, who by their heroic labors and by their advance of the frontier of Spain to California and Arizona had cast the greatest luster upon the Jesuit name in North America. The adventures, vicissitudes, and sufferings of these fathers were far greater than had been those of the south, for their journey to Vera Cruz was more than a thousand miles and for those of Sinaloa, Sonora, and Lower California the travel was by land and sea. Of the 678 Jesuits south of the Rio Grande, which made up the Province of New Spain, 104 were missionaries. Of these fifty were in Sinaloa and Sonora, nineteen in Tarahumara in the present state of Chihuahua, twelve were in the mission of Chínipas, sixteen in Lower California, and seven were south in Nayarit. [29] The fate of those of Chínipas and Nayarit we do not know; the others passed through the crucible of many and sometimes most painful adventures.

Chihuahua, where the fathers had a college, was the center whence radiated the missionaries of the Tarahumara country, and it was the capital of the province. Here the fatal word arrived June 30, and the several fathers of the college left immediately under guard for Vera Cruz. The townspeople, seeing the padres depart, offered to pay all the debts of the college could only the fathers remain.

It now became the unpleasant task of Captain Lope Cuellar, lately made governor of the province, to gather in and to conduct to Vera Cruz the nineteen missionaries scattered in their respective missions over the wild mountainous country of Tarahumara. The governor had no soldiers for this purpose, so he had to impress into service twelve or fourteen ragged fellows to attend to the arrests. He knew he could carry out his orders without the aid of a single man, for the submission of the padres was a byword; but for the people and the Indians, appearances had to be sustained.

Some days passed before departure for the far southwest could be arranged. The missionaries were under guard in their own house, but they were well treated by the governor, who allowed them to receive as many visitors as they wished. The Indian governor-general of the Tarahumares was making plans to travel the whole thousand miles to Mexico City with a delegation of his redmen to petition the viceroy in person that their padres be not thus torn from them. ....

After their ten days' mild retention in Chihuahua, the fathers set out, July 27, under guard for Vera Cruz. .... The missionaries arrived at Guadalupe at midday, September 16, just at a period when the forty hours' devotion was in progress. Word of their coming sped over the town, to the capital, and beyond. Soon the inn where the fathers were staying was packed with visitors, while the following day the three miles of road connecting the shrine with the capital was dark with people, coming to catch a glimpse of the padres. Fine ladies and noble señors came in their "carrozas," mingling with the rich and poor, Spanish and Indian, some trudging on foot, others on the back of horse or mule. ...

On October 7 all received orders to go to the port. Guarded by soldiers on horseback, they passed through this hot and insect-infested country, arriving at Vera Cruz, October 11.

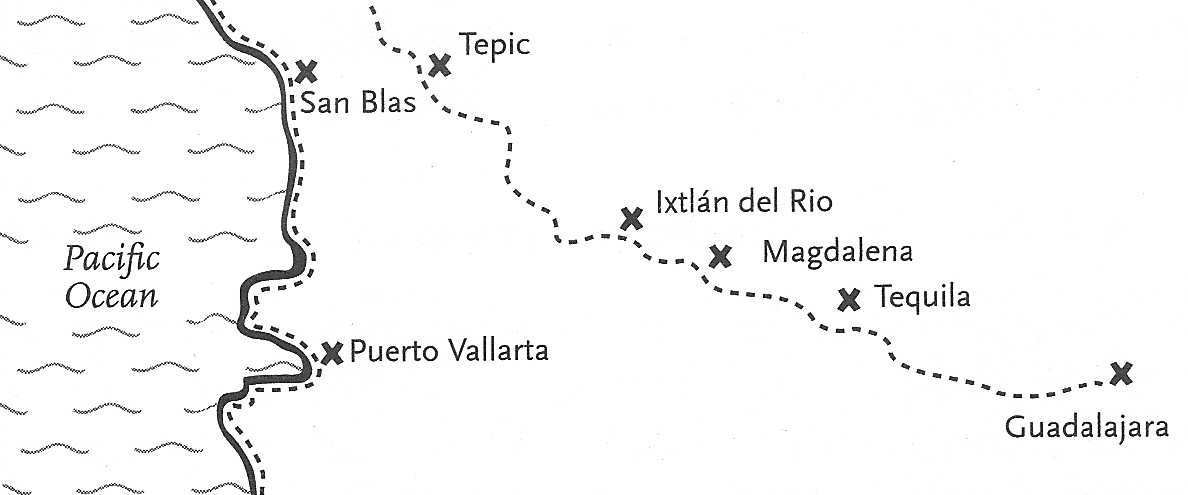

The Journey Of The Californians - Baja California

To Don Gaspar de Portolá, famed discoverer of San Francisco Bay, was given by José de Gálvez the unpleasant task of carrying out the royal order with regard to the missionaries of Lower California, where the Jesuits had planted nineteen major missions since Salvatierra first came to begin the work in 1697. Captain Portolá, sailing from San Blas, entered the Gulf of California, and after one more southerly landing came finally to the port of San Bernabé, close to the mission of Loreto. Two other ships carrying soldiers and the Franciscan successors to the Jesuits were driven back in a storm.

Portolá, to his credit be it said, proceeded with kindness and moderation. He sent word to the superior of all the California missions, Father Benito Ducrue, to come to confer with him at Loreto. Ducrue was fifty miles away at the mission of Santa María de Guadalupe and arrived at Loreto with three others only at the vigil of Christmas. The fatal decree was communicated by Portolá who ordered the superior forthwith to collect all his men, fifteen fathers and a brother, at Loreto that they might sail down to San Blas and thence take the road for Vera Cruz. ...

The two thousand neophytes of Father Wenceslaus Link rioted at the mission of San Francisco Borja when they learned their father was to be taken from them. ...

It required time for the padres to settle their respective missions, taking the inventory according to orders, and then to trudge to Loreto. In the meantime news came that the Franciscans had, after a voyage of eighty-three days, touched on the peninsula farther south. By the beginning of February all was ready for the departure of the Jesuits. Among the sixteen were six Spaniards, two Mexicans, and eight Germans. [42] The morning of February 3, Father Retz said the final Mass and Ducrue |19| preached a sermon. They embarked in a small craft unfit for sixteen men, while Indians and soldiers gathered to see them off. A calm delayed the vessel until the evening of February 4, when at long last, with lazily bellying sails, she slid out of the harbor. Don Gaspar de Portolá did not restrain his tears. [43]

After four days the put in at Matanchel, near San Blas, and prepared for their journey overland to Tepic and then to Guadalajara. Farther inland the exiles had to pass through more populous centers. They were received with ovations everywhere. ... taken to Vera Cruz, where they arrived March 27 after a journey of forty-four days. [45]

The Fate Of The West Coast Padres - Sonora and Sinaloa

The fate of the Jesuits of the west coast missions was the most harrowing experience as it is now the most harrowing in its recital. Through accident and incompetence the exiles were made to pass through horrible sufferings. The missions that these fathers served are among the most famous in all mission history both for the numbers brought into the fold of the Church and for the advance of the frontier of Spain beyond the present limits of the United States. .... . Even in the first half-century of their labors, the Jesuits in Sinaloa and Sonora had baptized hundreds of thousands, and by the time of the suppression had established there close to two hundred missions.

The decree of expulsion was first made known to the missionaries of Sinaloa and Sonora on July 25, 1767, almost a month later than word had come to their confréres laboring east of them and beyond the Sierra Madre in Durango and Chihuahua.

The rector of the north, Father Juan Nentvig, to whom the decree was intimated, summoned all the fathers of the two provinces to meet him at Mátape some miles west of the upper Yaqui river. In the meantime the vice-provincial and general superior of all this western section, Manuel Aguirre, officially deeded over all properties to the King of Spain. Fifty-one Blackrobes gathered at Mátape where the devastating news was broken to them. |21|

They had orders to go to Guaymas on the coast, there to await embarkation for San Blas. At Guaymas they were miserably housed in a ramshackle barracks of mud and straw without window, door, chair, or table; it was ill-smelling, rat-infested, hot. Fed on tainted food, with hot and salty water to drink, they developed scurvy and one of their number, Joseph Palomino, died. Here they were kept for months, from September, 1767, until May, 1768, and when they finally took ship, May 19, all of them were ill while only a few were able to walk the short distance from their hovels to the place of sailing. The rest went on mules or were carried on improvised litters.

This was the bad season in the Gulf. No captain of experience would have ventured forth at this, the summer time of storms and the rainy season. From October to March were the months of best weather on this choppy and treacherous sea. Nevertheless, they launched out in May with results that could have been foretold: storms, followed by oppressive heat, delayed and even blocked all progress and aggravated the condition of the scurvy-stricken padres. A climax of misery lay in the growing shortage of water. .. Finally, tossed and buffeted for twenty-four days, the bark was blown upon the coast of Lower California ...

Now the spot where the ship found anchor was but some fifteen miles south of Loreto, residence of Portolá and site of the mission whence the Jesuits of the peninsula had set out for San Blas four months previously. Word ran over the country that exiled Jesuits from the opposite coast were on the anchored ship. Indians came by the dozens down from their mountains to gaze again upon a Blackrobe and to kiss his hand whenever they could paddle close enough to the ship. They brought food as an aid to the sick and as a mark of devotion. The superior of the Franciscans came to visit the Jesuits and in Christian spirit consoled them in this their desperate plight. He interceded with Portolá that the fathers might be brought to shore to refresh themselves and be cured from their disease. The captain, fearful of his superior officer, José de Gálvez, would not grant the favor. Therefore, in ever-increasing heat, for it was now the end of June, the padres sweltered and burnt while the scurvy consumed their strength.

Finally, after fifteen days of agony, Portolá came himself to visit the missionaries. Their condition moved him; he relented, and they were allowed to leave their baking prison. Many of them were half dead. Here, treated to the more wholesome and varied diet provided by Portolá, fresh meat, corn, and a cup of gruel for breakfast, their health began to pick up. That which definitely cured them of their scurvy, however, was what the Indians carried down from the hills. Every evening they would come in with arms full of the mescal fruit. ... Thus were the fathers put into a sufficient state of health to be able to bear the hardships of the voyage to San Blas, seven hundred miles south. [54] |23|

On July 11, word came that the "visitador general" himself, José de Gálvez, had arrived in Lower California. Portolá, evidently alarmed, gave immediate orders that the party take off for San Blas, and the captain was commanded, under pain of death, not to land at any other port except in case of dire necessity. These orders, it seems, came from Gálvez. On the 14th all was in readiness.....

This, their second voyage, took them twenty-six days with trials, adventures, and dangers innumerable. The heat continued, the food was bad and then ran short, the water gave out. Storms battered the poor hulk and she drank great gulps of water. Arrived off San Blas they were set upon by a terrific electric storm followed by a cloudburst. ... At last, at ten o'clock the morning of August 9, the party disembarked at San Blas. ....

Their journey now lay overland east through Tepic and Guadalajara to Vera Cruz. The stretch to the town of Guaristemba was trying in the extreme. The rainy season was still on, and for certain hours of each day the rain fell in torrents. A new road cut to avoid a forest was now under water. The fathers were on horseback ... In places the water rose beyond the horses' bellies; sometimes the beasts stumbled in the mud at the bottom or struck obstacles that made them fall. More than once the wayfarers were pitched into the flood and had to struggle for their lives. They became separated, some had lost their mounts, and they straggled in to Guaristemba in the very extreme of misery. .... Arrived at Tepic thirty miles distant, a better sort of place, they were greeted and treated with loving kindness. The inhabitants accepted the spiritual ministry of the fathers and went quite universally to confession to them. ...

But these blackrobe missionaries had gone through too much. Though their hearts were consoled, for they had done much spiritual ministry at Tepic, a strange and mortal sickness began to seize them. Scurvy, poor fare, exposure in a steamy and unhealthy climate had done its work. The hand of a black plague was upon them. ... Several died here at Ixtlán, others dropped on the road to Guadalajara, others died in the great city itself. Twenty out of the fifty were taken. Of those who died at Ixtlán, one was the superior, Juan Nentvig. The people mourned and buried the Jesuits with honor and veneration. ....

Finally, after all these vicissitudes and sufferings, trials, and hardships, these missionaries of Sonora and Sinaloa arrived at Cádiz in Spain after two years of most unhappy traveling. The first group of nineteen arrived April 26, 1769; the second group of eleven, July 10, of the same year.

Imprisonment In Spain and Aftermath

The Spaniards of these missions of the west coast arrived in Spain only to find themselves made prisoners at the Puerto de Santa María, in the former Jesuit hospice ... The group was tightly crowded into the second floor of the hospice which they could not leave, not even to go into the chapel or patio. The windows were boarded up and they were guarded day and night, thirty-two soldiers with a sergeant marching to the house every morning to the beat of drum to relieve those who had watched during the night. A sentinel was placed at every turn. There were minute and rigid instructions, shutting out of all visitors, close inspection of food, change of clothing every eight days.

So it went on month after month, and the fathers settled down to a perpetual imprisonment. A year had not passed when the rigor of the confinement was relaxed. .... In 1775, most of the Sinaloa and Sonora missionaries were dispersed to various religious houses in different parts of Spain.

A few, however, were still-retained at Cádiz at the hospice of Puerto de Santa María. ... At length after eleven years even the corporal and his four guards were withdrawn, but by this time most of the remaining prisoners had died! And so closed a chapter of most extraordinary events.

Thus perished the "old Society," as the modern Jesuit styles it, so far as Mexico was concerned. A very similar story could be written about each particular Spanish and Portuguese colony, as about each particular country of Europe. Thus ended the service of twenty-four colleges in New Spain and six residences. Eleven seminaries collapsed and dozens of Indian schools were wiped out. Since the Jesuits of the old Society were admittedly the educators of the youth of the country, it can be understood what a blow to education was the expulsion of the Jesuits from Mexico. As far as the missions were concerned an historic work of great importance was undone. Approximately 200,000 Indians were under the care of the fathers in the missions when the blow of dissolution fell.

A sufficient number of trained missionaries was not at hand to take the place of the Jesuits. Therefore the missions in many instances disappeared, in most instances declined. The missions of the west coast and of Lower California had been of very particular importance, and the story of their development and progress takes its place among the great chapters of mission history in the world. Begun in 1591 by Gonzalo de Tapia on the Sinaloa, and spanning river after river, then carried by Kino to San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, Arizona, in 1697, and by Salvatierra across to Lower California that same year, this mission system had built up the background which made it possible for Spain and the Franciscan fathers to advance to Alta California two years after the expulsion. ....

"The Expulsion Of The Jesuits From New Spain, 1767"

Peter M. Dunne

Mid-America: An Historical Review

January, 1937; New Series Volume 8, Number 1

Excerpted parts of the article; for entire article, see below.

To download entire article,

click

The Expulsion Of The Jesuits From New Spain, 1767"

Imprisoned Jesuits

Jesuit Expulsion in Sonroa

Albert Stagg

The Spanish settlers who came in the wake of the missionaries had opened mines and established ranches. By government decree, up to four percent of all able-bodied Indians in each village had to take turns working in the mines. The Jesuits opposed this forced labor, for the settlers used the Indians to work their land as well and often ill-treated them. Because of siding with the natives, the Jesuits came into conflict with the settlers, who furthermore complained of being denied the sacraments on the grounds that such rites were performed only for the Indians. |10| Local government officials and parish priests also resented the presence of the fathers whose influence with the natives, they claimed, undermined their own authority.

Other charges were that the Jesuits put themselves above the law, refusing the comply with orders from the civil authorities, and were more interested in learning the Indian dialects than in teaching the Spanish language. This last accusation was particularly damaging, for the three basic principles of Spanish colonial policy were to convert the natives to Catholicism, replenish the royal treasury and expand Spanish influence and culture through dissemination of the language.

It is well to note, however, that up to one-third of the fathers of the Society of Jesus serving in the American missions could be foreigners; in fact Father Kino himself was an Italian. There were also Germans, Czechs, Austrians, Swiss and Frenchmen in the order; therefore, it would be surprising if they all had spoken good Spanish.

A further complaint reaching the viceregal court in the capital city of Mexico concerned the wealth of the missions. The lands around the missions were owned in common by the Indians; the Jesuits, acting as their guardians, stored the crops and distributed them as required. This was done to avoid food shortages when white speculators charged inflated [8] prices for foodstuffs. Each missionary received an annual stipend of three hundred pesos from the royal exchequer and a further 129 pesos for wine, oil and candles for church services. Unlike the parish priests, they received no contributions from their congregations. Yet, being hard-working, thrifty men, they made their missions flourish. Although it gave color to the exaggerated tales of the wealth of the missions, the donation by the missions of 2,000 quintals of flour and five hundred head of cattle to the Elizondo expeditionary force, while inspired by the Jesuits, was entirely voluntary. |11|

While such rumblings were being heard in Sonora, powerful forces in Spain were working against the Jesuits. The throne was occupied by Charles III, an autocratic Bourbon who, like others of his family, considered the Jesuits too militant and international to suit his absolutist ideas. After meeting with the council of ministers at the Pardo palace outside Madrid on February 27, 1767, the king issued a royal decree for the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from all Spanish territory. It was forwarded by the count of Aranda, president of the council, and received by the viceroy of New Spain, Marquess de Croix, on May 30, 1767. In writing to his brother, the marquess de Huechin, de Croix observed that his royal master was following the example set first by Portugal, then France, in expelling the Jesuits. A more picaresque version of Charles III's motive is that Aranda produced a forged letter from the Jesuit general in Rome to the superior of the central Jesuit house in Madrid, in which he declared that he possessed convincing proofs of Charles' illegitimacy and might publish them at an opportune moment. Aranda claimed that one of his trusted agents had abstracted the letter from the private papers of the Jesuit provincial. The king, accepting the letter as genuine, was so enraged by the calumny and the danger it posed to his throne that he proceeded with the expulsion. |12|

Fearful of disturbances if the news leaked out |*| since the Jesuits had many devoted pupils among both rich and poor, de Croix informed only the inspector general, Jose de Galvez, and Huechin's son, Caballero Teodoro de Croix, about the decree. Therefore, copies of the decree and the viceroy's instructions to the provincial authorities were written by the three men. The sealed packet containing the royal decree and the instructions to the governor of Sonora, Lieutenant Colonel Juan Claudio de Pineda, left Mexico City by special courier on June 6, 1767, but as the courier fell ill in Alamos, Sonora, it reached the provincial capital, San Miguel de Horcasitas, three days beyond the date fixed by the viceroy for Governor Pineda to open the packet and read the contents.

This mischance was responsible for hasty decisions, since neither Pineda nor his subordinates wished to appear neglectful of their duty. The Jesuits were taken from their missions precipitously and sent under [11] armed guard to San Jose de Guaymas, where they were assembled in rat-infested, dirt-floored, wattle huts, already crumbling and opening to a corral fouled by horses, mules and sheep. They were held in these intolerable quarters for nine months, suffering from intense heat, cold and damp until a small sailing vessel arrived at the nearby port of Guaymas. By the time they embarked, most of the fifty-one missionaries, {**] especially the elderly, were in poor health. |13| Their destination was San BIas, but due to storms and inexperienced navigators the voyage which normally took six days lasted nearly three months.

When they landed, famished, weakened by scurvy and in rags, they were obliged to travel immediately to Guadalajara, twenty of them dying along the way. [14] From Guadalajara they travelled to Vera Cruz from where, in March 1769, they sailed for Europe.

The Jesuits were not always blameless; some no doubt were arrogant, but on the whole their record was exemplary. To have abruptly ended their missionary work of one hundred and fifty years in such a brutal manner was shameful. Three of the Jesuits deported from New Spain were born in the Real de los Alamos, Sonora. One of them, Father Jose Rafael Campoy, of a patrician family, was a noted scholar and author, much respected in academic circles in Bologna, Italy, where he died in 1777. That a pioneer mining town could produce a scholar of international reputation is a tribute to Alamos. |15|

With the departure of the Jesuits, many Indians fearing that they would be enslaved by the royal trustees, who assumed control of the physical assets of the missions, abandoned villages and farms, took to the mountains and reverted to a primitive existence. Progress in Sonora suffered a severe setback, and the Indians, deprived of their protectors and mentors, became even more distrustful of the whites, a feeling which persists some two hundred years later, especially among the Mayos and the Yaquis.

[*} Serious disturbances did occur once the expulsion order was known in Queretaro, Michoacán, Celaya and San Luis Potosi. Alberto F. Pradeau, "La Expulsión de los Jesuitas de las Provincias de Sonora, Ostimuri y Sinaloa en 1767" (Mexico City: Antigua Libreria Robredo de J. Porrua e hijos, 1959), p. 117.

{**] Thirty-one were from Sonora and twenty from Sinaloa. Father A. 1. Gonzalez already had died at San Felipe de Sinaloa. [11]

Albert Stagg

Chapter 2 "The Expulsion of the Jesuits"

"The First Bishop of Sonora: Antonio de los Reyes, O.F.M." 1976

Notes

|10| Francisco R. Almada, Diccionario de Historia, Geograjia y Biograjia Sonorenses (Chihuahua: Impresora Ruiz Sandoval, 1952), p. 474.

|11| Father Kieran McCarty, superior and historian, Mission San Xavier del Bac, Tucson, Az.

|12| Zephryn Engelhardt, Missions and Missionaries of California, vol. 1, 2nd ed. (Santa Barbara, California: Mission of Santa Barbara, 1929), p. 317.

|13| Alberto F. Pradeau, La Expulsion de los Jesuitas de Las Provincias de Sonora, Ostimuri y Sinaloa en 1767 (Mexico City: Antigua Libreria Robredo de J. Porrua e hijos, 1959), pp. 79, 85.

|14| Roberto Acosta, La Ciudad de Alamos: Memorias de la Academia Mexicana de la Historia (Mexico City: Imprenta Aldina, Robredo y Rosell, 1946), p. 52.

|15| Ibid., p. 53.

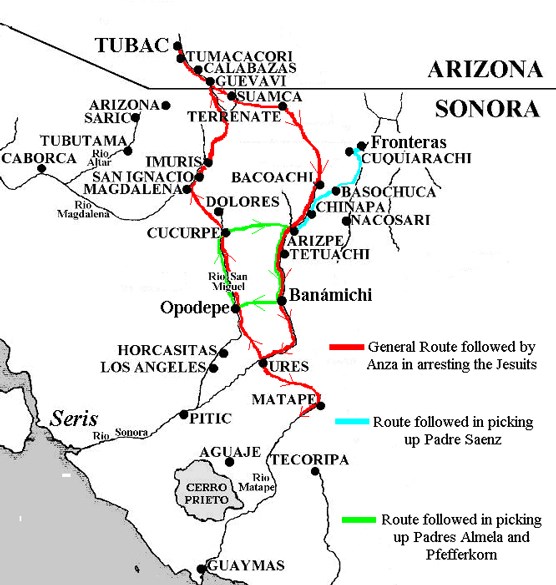

Editor Note: A half century after Kino's death, the despotic Bourbon Spanish King secretly ordered the imprisonment as enemies of the Crown all Jesuits in the Spanish empire. Among the many charges, the Jesuits were blamed for the Madrid Bread Riots where the Spanish King and his government were endangered of being overthrown for several days. On July 25, 1767, Captain Anza of the Tubac Presidio was charged under penalty of death to carry out the King's order in Sonora. He coordinated the arrest of the Jesuit missionaries including their superior Padre Roxas who was Anza's childhood mentor and best friend.

Anza Route Map in Arresting Jesuits During Expulsion From Sonora

Anza and the Jesuit Expulsion

Carlos R. Herrera

The Jesuit expulsion of 1767 was one of the most drastic measures taken by the Bourbons to achieve royal absolutism. The padres had been accused of inciting bread riots around Madrid in 1766 and turning the general populace against the king. Carlos III believed the Jesuits harbored an unflinching allegiance to the pope that undermined the ideal of absolutism; even worse, he accused the black robes of plotting against his life. In his imperial eyes the papist-minded priests had to go, they had to be removed from the empire. [15]

Regarding New Spain, the king accused the Jesuits, especially those serving in Baja California, of challenging his authority by attempting to created theocratic societies among the local Indians. [16] Carlos III recognized that such efforts subverted the true essence of Spain's mission program. By making the other Indians dependent on the missions, the Jesuits had in fact prevented the full transformation of natives into active, tax-paying citizens of the empire. In Sonora, the crown's attack on the Jesuits found favor with many land-hungry colonists who wished only to see the missions secularized. Others, like Anza, questioned the expulsion because ties promised to sever the close ties they had nurtured with the Jesuits.

Carlos III issued the Jesuit expulsion decree in February 1767. In July, Sonora's governor, Juan Claudio de Pineda, received the proclamation with orders to proceed with its execution in a highly cautious and secretive manner. Pineda appointed the captain from Altar, Bernard de Urrea, to oversee the general roundup of the Jesuits. However, Pineda ordered all his captains - including Anza at Tubac - to carry our the actual arrests. Pineda feared that incarcerating the Jesuits might set off an uprising among Indians and colonists who had remained loyal to the padres. He figured, however, that Anza might help douse inflamed emotions and prevent conflict; therefore he assigned to Anza the task of informing Father Visitor Carlos Roxas of the king's decree. He hoped Anza's longstanding friendship with the Jesuits might contribute to an orderly expulsion process by calmly exposing the priests to their fate. [17]

On 23 July 1767, Anza broke the seal of the instructions he received from Pineda. He read the king's royal decree and reflected on its meaning. In light of Anza's relationship with the padres, Pineda must have wondered if Anza would refuse to carry out the expulsion decree. This Pineda could not afford. Anza was much liked and respected in the colony, and he might sway the populace against the state on the Jesuit issue. The captain was also young, ambitious, and a faithful servant seeking promotion within the imperial machine. Pineda knew this, and so he played on Anza's sense of obedience by ordering him to complete his charge without any delay. Pineda signed off by stating he had no doubt the captain would see to the king's will with honor and zeal, and that in so doing, he would provide evident proof of his fealty to the crown.

On 25 July 1767, Anza travelled to Arizpe to meet with his friend and confessor. Details of the reunion between Father Roxas and Captain Anza remain a secret, perhaps in part because the clerics were ordered to observe a strict and complete silence regarding their expulsion; they had been forbidden to discuss the matter even among themselves. With stoic resolve, Anza informed Roxas that as head of his order he must sway his brethren to congregate at Arizpe with due haste and with no excuse for delays. The padres were to be relocated to Mátape, and then sent on to the port of Guaymas, where they were to live under house arrest until ships could be made available for their transport to central New Spain. [18]

Anza must have left Arizpe with somber spirits, but he pushed forth to fulfill his charge of gathering and transporting those Jesuits serving in missions along the Río Sonora. By August 5, he reported to Governor Pineda from one of these missions, perhaps Aconchi: "My Governor and sir, I have almost completed my commission here and hope to leave for Mátape, where I expect the three missionaries who were unable to accompany me, but who were conducted to this site by the commissioner [I appointed for the task], have arrived. I would have departed by now, but Father Perera's illness, and the need to let him recuperate so he can travel, has detained me. [19]

Nicolás de Perera, a native of Zacatlán, New Spain, had refused to be left behind at Aconchi while his fellow priests suffered the indignity of arrest and exile. He informed Anza that he would gladly follow his brothers as best he could. Anza accommodated Perera by ordering the construction of a stretcher that, rigged to mules, carried the ailing padre to his imprisonment. [20]

Much to Governor Pineda's relief, Anza carried out his order without incident at the height of the summer. In August 1767, he bid farewell to his lifelong friend, Carolos Roxas, and informed his superior that Carolos III's will had been fulfilled. Although Anza did not question in public the absolutist ideal that underlain the expulsion, he was not so sure that Sonora's Indians would be better off without the black robes. In the end, Anza summed up his feeling about the Jesuit affairs when he wrote to the governor, "After all, the king commands it and there may be more to it than we realize. The thoughts of men differ as much as the distance from earth to heaven." [21]

The Jesuit expulsion sparked and intense debate in Sonora between church and state officials regarding the failed assimilation of natives. Franciscan gray robes who replace the Jesuits blamed military types such as Anza for failing to stem an increase of Apache raids into northern Sonoran. The fear of meeting a violent death, the friars claimed, had lead many Indians to desert their missions. Likewise, Spanish colonists who had settled in peripheral regions like the San Luis Valley began to abandoned their homes and seek shelter at more fortified towns as early as 1768. At Tubac, for example, Indian and Spanish refugees congregated near the presidio in hope that Anza would, somehow, keep them alive. Anza made no excuse for his inability to defend Pimería Alta. He insisted that increased Apache raids had resulted from Spain's demand that he first deal with warring Seris who were located further south in in Sonora. [22]

Carlos R. Herrera

Juan Bautista de Anza: The King's Governor in New Mexico

Jesuit Expulsion: 1767

Chapter 3, Servant of the Crown: 1756-1778

Part I, Anza's Sonora

Google book link

https://books.google.com/books/about/Juan_Bautista_de_Anza.html?id=91ktBgAAQBAJ

Footnotes

[15] For King Carlos III's motivation and decision to expel the Jesuits from the Spanish empire, see Lynch, "Bourbon Spanish", 280-290. For the expulsion of the Jesuits from Sonora, see Kessell, "Mission of Sorrows", 181-88.

[16] For a history of the Jesuit mission front in Baja California, see Crosby, "Antigua California".

[17] Kessell, "Mission of Sorrows", 182.

[18] Anza's orders regarding the Jesuit expulsion of 1767 are located in "Instrucción particular y reservada que devera observar el comisionado del rectorado del Río Sonora, Don Juan Bautista de Anza, Capitán del presdio de Tubac, para la excucíon del lo resuelto por su magestad en su Real decreto de 27 de Febrero de este año [1767], BNAF 33:708, ff. 5-7v.

[19] Anza to Pineda, place unknown, 4 August 1767, BNAF 236:912 ff. 11-11v. It is possible that Anza wrote this letter to Pineda from Aconchi, because it was there that seventy-one-year-old Father Nicolás Perera lay ill and unable to ride south to Mátape.

[20] Father Perera did not survive the Jesuit expulsion of 1767; he died en route to Mexico City, at Ixtlan del Río in Nayarit, on August 29 1768. See Zelis, "Catálogo de los Sugetos", 32, 167.

[21] Anza to Pineda, Arizpe, 15 August 1767, BNAF 39:886, quoted in Kessell, "Friars, Soldiers and Reformers", 14.

[22] The increase in Apache raids into northern Sonora in the late 1760s and the initiation of the Seri Wars are aptly cover in Kessell, "Friars, Soldiers, and Reformers", 21-49.

Expulsion in Mexico City, Sonora and Baja California

Charles W. Polzer

The third general assumption [about Jesuit lost mines and hidden treasure] employed by the legendeers is the "sudden" expulsion of the Society of Jesus from the Spanish empire. Although the expulsion of the Jesuits constitutes one of the most fascinating sagas in Spanish colonial history, the whole story has never been told. It may never be told, for that matter, because the true reasons for the action were locked in the heart of the King, Carlos III, and his counselors. Whatever may have leaked into the record was lost when the King's Council ordered the destruction of the records some years after the imperial fiasco. History, like the Jesuits who were exiled, has been left in a bewildered ignorance. Nothing similar to the expulsion had ever been accomplished in the history of the world to that time. Leading religious scholars, university professors, missionaries, preachers, and theologians were simultaneously exiled from the Spanish realm throughout the world. [1] It was a master stroke of imperial power that seemed like arrogance to some and genius to others.

A brief characterization of the expulsion will serve adequately for the purposes of this paper. In the late spring of 1767 sealed orders were sent by Carlos III to all portions of the empire. On the night of June 24th the seal was to be broken in the presence of the highest appointed authorities. When the orders were opened |180| in New Spain, the Visitador, José de Galvez, found himself charged with the arrest and seizure of all Jesuits within twenty-four hours. The Jesuits were to be permitted to take only their breviaries and such garments as would be absolutely necessary for the journey. Ships were to be provided for their involuntary exile at Vera Cruz.

Galvez was true to his charge. Couriers sped along the roads to carry the news to the provincial governors before rumor could reach the Jesuits on the missions. That very night in Mexico City some 3,000 troops, both infantry and dragoons, moved out from their garrisons and surrounded the five Jesuit residences. At dawn the units swarmed through the houses, rousting the sleeping Jesuits from their beds. Drowsy and disbelieving the religious were lined up in the chapel. At the Colegio San Pedro y San Pablo Galvez with 300 men tensed for action; the men charged the house, arrested the residents, and read the decree of expulsion to the ninety men assembled forcibly in the chapel. One fainted; one screamed; a few wept. Instead of the bloody struggle he anticipated Visitor General Galvez met only compliance; the priests and brothers filed past him in silence to get their breviaries, one book, and the clothes permitted them for the trip back to Spain.

In accord with the orders of the King the detachments of troops impounded all books sealed all records, and surrounded all the property with armed guards. The treasury of the Colegio was seized and the 80 pesos recovered was kept for the King (apparently they didn't present him with the 40,000 pesos of bills still outstanding). In Puebla at the Colegio Espirito Santo the whole residence was ransacked. The floors were ripped up, walls were smashed apart and even the toilets were meticulously searched. The thirty fathers in the Casa Profesa knelt to hear the decree of their expulsion and responded by chanting the "Te Deum." While this curious ceremony took place, the 100 soldiers in charge of the search operations became infuriated at the poverty of the house and seized the sacred vessels in the chapel. Morning came. Mexico City was eerily silent. No churches tolled the Angelus. The streets were swarming with soldiers who roughly turned men and women away from the churches. Religious services were banned. One old man whose poor hearing prevented him from grasping the warnings walked toward a church for morning Mass and was shot in his tracks. No one could speak to a Jesuit on penalty of death. Although the people protested, the padres urged patience and obedience to the decrees, but when the time came for the trip to Vera |181| Cruz, Galvez' men could only commandeer eight of Mexico's 4,000 carriages!