An Error In The Map

Chapter 08

Padre Kino and the Trail to the Pacific Online

|110|

Chapter 8 An Error In The Map 1698

During the two years following Padre Kino's trip to Mexico City he established missions to the north, in Arizona, stocked them with cattle, sheep and goats, made frequent trips to instruct the people in the Holy Faith.

One day in midsummer of the year 1698 he was at Remedios. The church was not yet finished, but the walls were more than nine feet high and branches had been intertwined to make a leafy roof. Padre Kino looked out at the sea of dark heads, many from the distant missions he had established, bowed in reverence at the end of a solemn Mass. There were a few Spanish gentlemen from a nearby mining town, but most of the crowd were Pimas, come here to kneel before the altar, to worship God and pay honor to Our Lady. All had marched in the procession that morning, carrying a |111| beautiful new statue of Our Lady of Remedios through the village named for her, installing it here beside the altar. How sad it was that such faithful people must go back to missions without padres and which he himself could visit so rarely.

In the throng he recognized Chief Coro, and Chief Humari from the San Pedro River, and the Pima captain and governor from Bac. There was another Indian governor from a village on the Gila River two hundred and fifty miles away. What wonderful people they were!

Padre Kino began to speak. This, he said, had been a year of great tragedy, but of triumphs even greater. The Apaches had driven the padre from the mission at Cocóspora and destroyed the church, the house, the whole village. Another small settlement near Chief Coro's town of Quíburi had been sacked and some of its people killed. But the valiant Coro had gathered five hundred Pimas and avenged the murders, fighting hand to hand with the Apache chief and, when he had killed him, pursuing the Apaches and killing or wounding more than three hundred of them. When the news of that great victory reached San Juan, General Jironza himself summoned Chief Coro to the fort, so that he might be suitably rewarded. |112|

"There is peace throughout the lands of the Pimas," Kino ended. "At many of your towns are ranches where you are raising sheep and cattle, and fields for the growing of all kinds of grain. Tend them well, so that the padres for whom you ask may come to you."

Kino dismissed them and they turned to the feast that had been prepared, hunger whetted by the smell of roasting beef which had drifted from the cooking fires since daybreak. Some of the more important chiefs were given hot chocolate to drink. When they left Remedios they were a happy lot, well fed, and excited over the prospect of seeing Padre Kino again soon.

"Within eight or ten days I must go to the Gila River and the Sea of California," he had said. "Tell the new people of the coast that I am coming." The chiefs hurried homeward, each of them hoping he would be chosen to go with the padre as guide and companion.

Padre Kino hurried home too. He was feeling feverish and weak again. He would have to rest a little before this next journey, but while he rested, he could plan! He must find an overland route to California if it existed! The reasons were more pressing than ever.

Padre Salvatierra had been in California since the previous September, and had taken up exactly where Padre Kino left off twelve years before. His letters made Padre Kino weep, |113| but they were tears of joy, for the Indians of Lower California had forgotten neither Kino nor the Faith. Hulo had turned up with his father and while poor Chief Ibo was dying of cancer, Kino's prayers for him had been answered, for Salvatierra had arrived in time to baptize him. The lists of Indian and Spanish words compiled by Kino and the other padres were a great help, and it seemed that at last a permanent mission had been established on the inhospitable shores of California.

But the same difficulties suffered by Kino and Admiral Atondo were recurring. The Sea of California was as rough and treacherous as ever and although there were more plentiful supplies on the mainland than there had been during the drought of 1685, it cost more to ship them. "I paid six thousand dollars to ship twenty cattle from Mexico to California!" wrote Salvatierra and Padre Kino nodded unhappily as he read.

He put down the letter and closed his eyes. The fever made him a little lightheaded. He knew very well he was here in Dolores, on his own hard bed, yet all at once it seemed he was at Jesuit headquarters, in Mexico City, saying to the provincial, "I will explore the country far to the north and west, find out for myself whether California is island or peninsula!" |114|

How long ago was it when he made those brave plans? Twelve years. He had been at Dolores for twelve years and he still had not traced the mysterious Sea of California to its northern boundaries.

A chill shook him, but he fought it off, pulled the blanket tightly around his shoulders and made himself sit up. When his head cleared he struggled to his feet, got to the door and called for young Marcos. The fat housekeeper bustled, scolding, from the kitchen, but at Kino's insistence, called the young Pima foreman. When Marcos appeared, Padre Kino fired a whole string of orders.

"What are you saying?" cried Marcos, not waiting for the padre to finish. "North, west—where are we going? Who is going with us? You are too sick to travel anywhere, I think."

To Marcos' amazement, color was coming back into Padre Kino's face. He dropped the blanket to the floor, straightened, walked with almost his customary firm step to the door opening onto the plaza and threw it wide.

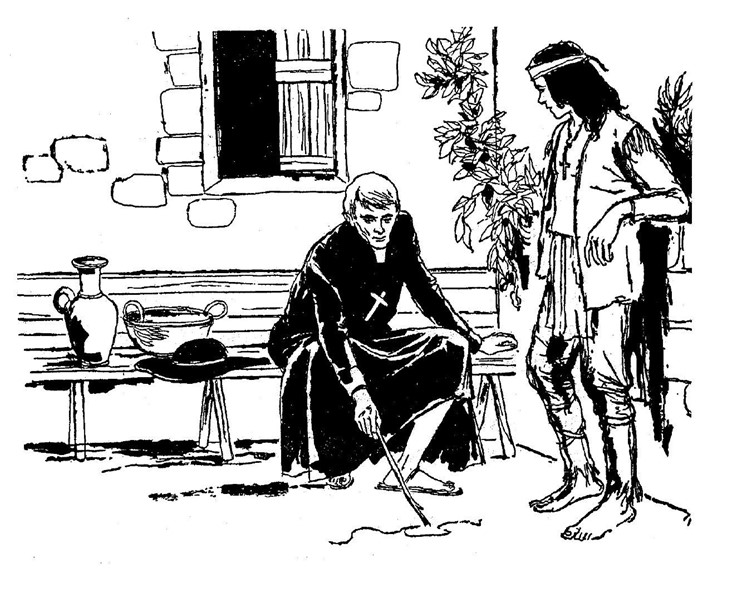

"Hand me that stick," he commanded. "I will show you where we are going," and he began to draw a map on the dusty earth. "We go north, through Bac to the Gila River. That river runs west, is it not so? We follow, |115||picture: Padre Kino began to draw a map on the dusty earth| |116| to the west. When we reach the Sea, we turn south toward Caborca. It is a long journey and by the time we reach there, our pack animals will be tired, so we will exchange them for fresh ones. Do you see? No? Well, do what I tell you, anyway. We will leave in the morning. General Jironza is sending a Captain Carrasco to go with me."

Marcos hurried away, shaking his head. He had heard all about the proposed journey, knew, in fact, that the military escort was due in Dolores today, but neither he nor anyone else in the village had believed Padre Kino could possibly recover in time to leave tomorrow. Something must have happened to cure him, thought Marcos. A miracle. That was it. Surely the great St. Francis Xavier must have done it!

Two days later the pack train crossed the divide at about the spot where Nogales, Arizona, would one day stand, and headed down the fertile valley of the Santa Cruz River. They were met at Bac by Chief Coro, and the Spanish officer, Carrasco, listened to this Indian military leader with admiration and approval.

"I have moved my people from Quíburi for a while," said Coro. "The Apaches are thirsty for our blood. We will stay away from the border until they forget a little." |117|

Captain Carrasco nodded. "It is a wise general who knows when to retreat a little."

He strolled away to look over the town and Coro said, "Where are the rest of the soldiers? Was the captain not afraid to come alone?"

Padre Kino smiled. "If he was afraid at first, he is so no longer. We have been welcomed everywhere, as always."

"And where do you go now?" asked Coro, hoping he would be invited to go along. He was disappointed when Kino outlined the journey and mentioned the guides waiting for him at the river.

The padre was not as well as he looked. Two days later he was forced to give up climbing a mountain from the top of which he hoped to trace the course of the river. But after a day's rest he insisted they go on.

The guides had given him disturbing information. Instead of running west, they said, the Gila River turned south in a big bend. There were many villages to the south. They all wanted Padre Kino to visit them.

"If the river truly does run south," said Kino, "we can go in that direction and reach the place where it empties into the Sea of California."

Captain Carrasco had his doubts about the river being anywhere near when the party started south the |118| morning of October 2. It looked like desert country to him. And their only water supply was what could be carried in gourds. At noon the padre permitted each man a sip of water, just one sip, and as the afternoon sun crossed a cloudless sky, the captain began to calculate how far they had come and whether they had enough water to take them safely to the next spring— if there were springs in this desert.

Pinacate 1st via O'odham

They had traveled about thirty miles when a cry came from the head of the column. "Someone comes!"

Carrasco strained his eyes to see, blinked against the glare of late afternoon and looked again. Four Indians approached. On the shoulder of each was a tall pottery jar and as the party rode up they welcomed it with plentiful draughts of the most delicious cool water Captain Carrasco had ever tasted.

Soon he glimpsed a field of melons, green and welcoming among their drying vines. Then they were in a little village with more than sixty Indians lined up with gifts of corn, beans and watermelons. No white man had ever visited them, but they had heard of Padre Kino.

The next night they were welcomed by over seven hundred Indians with flaring torches, found a house prepared for them, crosses erected along the road, |119| arches across it. Fires burned in front of the houses and the warmth felt good to Carrasco. The days were still hot at this time of year, but as the sun dropped, so did the temperature. By midnight he was chilled in spite of the fire and glad to roll in his blankets inside the little adobe house. Padre Kino did not seem to notice. He was still talking to the chiefs and headmen when Carrasco dropped off to sleep. And he shook the captain awake next morning just as the sun's first rays slanted across the village roofs. Time for Mass.

Was there no limit to the good padre's endurance? wondered Carrasco. He himself was too tired to get up; besides he was worried. The Pimas of the party had been carrying on a running argument among themselves for three days concerning the route they followed.

"So far there has been water, yet who knows when there will be only sand?" said a muleteer.

Padre Kino heard him and met the objection head on. "We will load one of your mules with gourds and water jars. Get some crates built to hold them, so they will be ready."

"But, Padre," said a second, "even if we have water, there is no grass near the coast."

"Then we will carry grass with us," said Kino. |120|

"It is not water and grass that concerns me," grumbled a man from Dolores. "Even at this time of year, the heat at the Sea of California burns so you cannot stand it."

"Mules will not travel if it gets that hot," said the driver of the train.

"Then we will travel at night." Padre Kino turned to the chief of the village. "Bring the old woman here—the one who came today from the coast with snails and little shells from the Sea."

The old woman, stooped from carrying a pack, approached the group. "Look at her," said Kino. "She came alone from the very shores of the Sea. How can men like you refuse to make the journey?"

One by one they shrugged and turned away. Carrasco noticed that thereafter they traveled with more confidence. Even the mules seemed to walk a little faster. The following day they reached the little village of Sonóita and here the map maker acquired some new guides and a great deal of encouragement regarding the rest of his proposed journey.

"You will not need to carry water with you," said the chief. "The Sea is near and there is water and grass on the way." |121|

And so it was. A ride of forty miles around the south end of a mountain was blessed with a good road, plenty of water, grass and the waving leaves of spiky reeds which always meant a swampy area. That night while they were eating calabashes prepared for them by friendly natives, Kino questioned the guides.

"How far to the Sea?"

"It is very near." The native pointed. "From the top of the mountain you can see the mouth of the Gila River."

"Yes," nodded the chief, "and beyond it, on the very big Colorado River, there are people who have big fields of corn and beans and cotton. Calabashes, too." Kino's eyes shone. He turned to Carrasco. "Let us go to see those people."

But Carrasco had had enough. "We have no relay animals," he said, "and who knows how far these can travel?"

Reluctantly, Kino agreed. "But if I cannot go to the mouth of the Gila, or the river beyond, I will see it from this mountain," he vowed, and next day rode with the guides seventeen miles up a rough trail to the summit. During the long climb he wondered, and prayed. Would this be the day he found the answer to |122| his question? Would he be able to see California, across the wide waters? And the Sea of California, suppose he saw its northern limits! He prayed he might— but when he reached the summit, the air was hazy. Below them stretched the Sea, and that was clear enough, with sand dunes between it and the mountain. But beyond? His eyes could not pierce the haze.

"What do you see to the north?" Kino asked the guide.

"I do not see very much," said the Indian, "but I know what is there. Far up that way the Gila River and the Colorado River come together. Then they flow southward into the Sea."

"Are you sure?" cried Kino. Much as he wanted to believe the fellow he could not. He would have to go and see for himself. It meant another journey, an even longer one—but he had learned enough to know that he must make changes in his latest map. On it he had drawn the Gila and the Colorado flowing side by side, each emptying into the Sea at a different place. If they flowed together—but he still did not know whether California was island or peninsula.

On the tedious hundred-and-thirty-mile ride south to Caborca, Padre Kino was silent much of the time, his mind busy with a new map, with plans for an expedition |123| from Dolores to Sonóita and northwest to the place where the Gila joined the Colorado.

At Caborca they picked up fresh pack animals, but before they headed east toward Dolores, Padre Kino took Carrasco out to look at the boat, begun four years ago when Lieutenant Manje helped to fell the cottonwood tree. Captain Carrasco had heard the story and looked with interest at the shaped timbers and keel.

They looked very odd out here in the desert, but there was one good thing about a dry climate: wood did not deteriorate. Now that Padre Kino had once again received permission to work on the boat—for there had been another change in the Father Visitors and the new one would like to see the boat completed—Kino gave orders to some of the men to cut boards for the deck.

Captain Carrasco shook his head, stopped, looked at Kino and marveled. If Padre Kino said so, the boat would probably be finished and taken to the Sea. It might even float! This Kino could do anything. Just ask a man who had traveled with him for a month!

They went on to Dolores where Carrasco said good-by to Padre Kino and hurried on to San Juan. There the captain made a long report to General Jironza. They had traveled almost eight hundred miles in twenty-five days. Kino had baptized four hundred Indians and |124| Carrasco had counted more than four thousand people, handed out more than forty canes of office.

"Padre Kino must be well satisfied with his expedition," said the general, but Carrasco shook his head.

"I do not think so. All he can talk about is an error on his map and his next journey to the northwest." |picture: drawing of pen and compass (124) |