The Devil's Highway

Chapter 09

Padre Kino and the Trail to the Pacific Online

|125|

Chapter 9 The Devil's Highway 1699

It had not looked far to Padre Kino from the top of the mountain near Sonóita to the place where the Indians said the Gila River flowed into the Colorado. But distances are deceptive in the clear, dry desert air. What appeared to be fifty miles was well over a hundred and twenty. And the terrain was some of the most difficult in all Sonora and Arizona for the traveler, so difficult it became known as El Camino del Diablo, the Devil's Highway.

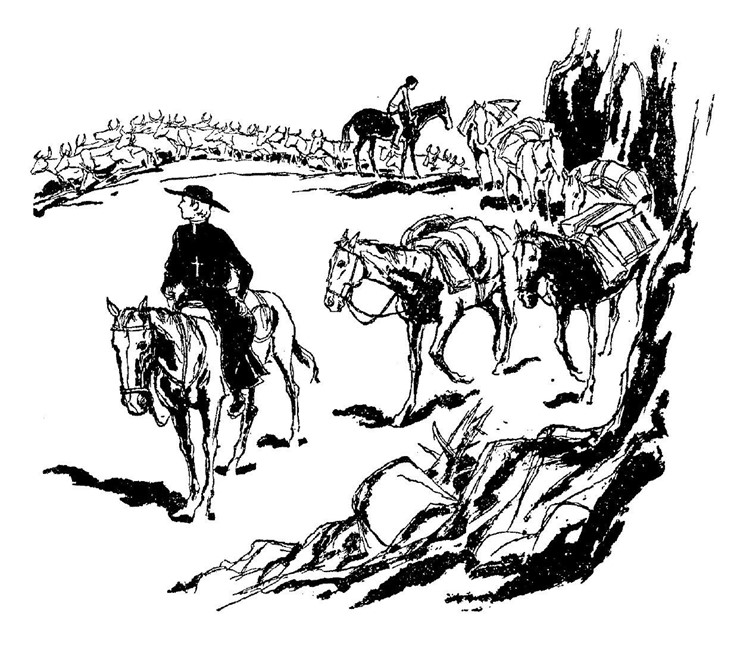

It held no fears for Kino, but as an experienced traveler he made more elaborate preparations for this expedition than for the earlier one. On the 16th of February, 1699, when he arrived once more in Sonóita, his equipment included eight loads of provisions and eighty horses. In addition he had his Pimas drive thirty six cattle from Dolores, with which he intended to establish a ranch. For Padre Kino meant to make this |126||picture: Padre Kino carried many provisions on the expedition that set out to explore the Gila River| |127| little village of Sonóita a base headquarters for further explorations in the northwest.

With Kino was his old friend Manje, a captain now, acting as military escort. They followed their customary procedure at Sonóita, with Manje talking through an interpreter to the chiefs and the padre preaching to the people. All day and all night he preached and the sleepy Manje had a hard time to keep awake during the early morning Mass.

They left their tired horses at Sonóita and were riding fresh ones, but even these did not have much stamina. On the second day of travel, crossing barren plains with no pasture, the horses began to weaken. After a three-day ride through treeless mountains, finding only water here and there in natural tanks in the deep rock and almost no food for their sullen animals, they reached a place which, the guides said, was not far from the Gila River. But that night their horses could go no farther, and as there was a little water here, they struck camp.

It seemed like a miracle to find trees and grass the next morning. It was too early in the year for the most nourishing forage, but by that time the starving animals would have eaten the bark from the trees. They |128| grazed all day along the banks of the river, filling their paunches with the spring grass.

As usual, Manje was counting Indians and observing their peculiarities. These were a mixed tribe, Pimas and Yumas. The men wore no clothes at all, the women nothing above the waist. They were a handsome lot, much lighter in color than the Indians of Sonora. Some of the women were really beautiful.

The next day a hundred Yuma men came from a settlement eight miles farther down the river. The padre preached to them, and Manje presented a few small gifts along with a beribboned cane. They brought gifts of their own to these strange white men—gourds full of flour, beans, and bread made from the fruit of a tree. Having established the fact that they were friends through the exchange of gifts, Padre Kino began to question the newcomers about the distance to the Sea and the place where the rivers emptied into it.

"One says it is a journey of six days," reported the interpreter, "but another says it is only three."

"We cannot take you to see it," said the Yumas. "We fear the people who live there."

"I am going anyway," said Captain Manje stubbornly. "I have not come all this distance to turn back now." |129|

Padre Kino put a hand on his arm. "These Indians do not know us. For the present we must do as they say."

"We cannot even go to see where this river empties into the Colorado?"

"No, my son," said Kino, "we cannot."

Manje looked at him. The good padre was as exhausted as his horses had been. His face was drawn, his eyes heavy.

"Go and rest," said Manje abruptly. "I will ride to the top of that high mountain to the west. The interpreter will go with me." And he set out as soon as his horses could be caught and saddled.

"I saw the place where the rivers join," he reported that evening, "but it was too foggy to see anything else."

"I am glad to know about the rivers," said Padre Kino, then, his eyes brightening, "I have been making discoveries, too. Some of the old Indians here remember a white man who came many years ago with horses and soldiers."

"That must have been Oñate, one of our explorers," said Manje. "He came through this country almost a hundred years ago. I doubt if anyone here remembers him." |130|

"Perhaps their fathers told them," Kino smiled. "But they themselves saw a wondrous thing when they were boys. A beautiful white woman, dressed in white, gray and blue, in a dress that came clear to her feet, appeared to them and spoke of God. Some of the Indians shot her with arrows, but they could not kill her. She went away, but in a few days she came back."

"Padre," exclaimed Manje, "I heard the same story at Sonóita. I did not believe it—but if these Indians saw her too—"

Kino nodded. Young Manje and he were thinking of the miraculous appearances in this new world of a Spanish nun, María de Ágreda who, although she never left her convent in Spain, preached again and again to the Indians of New Mexico. So, she had come here, too.

"That was about seventy years ago," mused Kino. "These old chiefs are at least eighty. They could remember her. It is possible."

His blue eyes looked westward. "They tell of other travelers. North and west of here is the ocean. White men sometimes come from there to trade. No one knows who they are, but they come overland from the ocean. Do you know what that means?"

Manje laughed. "How do you know they come over |131| land? You must not believe everything these Indians tell you, Padre Kino! If men came from the ocean, on land all the way, it would mean that California is a peninsula, when we know it has to be an island or Sir Francis Drake could not have sailed around it!"

Kino frowned but held his tongue. He was not ready for an argument on this question. Not yet. He picked up a big blue shell and Manje, glad to change the subject said, "What have you there?"

Kino handed it over and Manje said, "Why it is like the shell you keep on the table, at Dolores."

Kino nodded. The natives had brought him several of the big abalone shells this morning, the first he had seen since that long-ago trip to the west coast of California. Where had these come from? he wondered. Had traders brought them from the shores of the Pacific Ocean? Impossible to find the answer on this expedition, but perhaps the next time he came, he could make friends with the Indians farther down the river. Perhaps they would know.

The next morning they started east along the south bank of the Gila River. Again they traversed strange country, but it was a pleasant journey, always within sight of cottonwood trees, with plenty of water and pasture for the horses. In six days they were back in |132| Padre Kino familiar territory. On March 7 they were at San Xavier del Bac, where thirteen hundred people assembled to celebrate their arrival.

It rained that day, a heavy downpour that sent the river out of its banks and made seas of mud out of the roads. Padre Kino was happy to stay awhile and proud to show what the people of Bac could do. They had harvested and stored a hundred bushels of wheat in an adobe house. The cattle and horses had increased many times since Padre Kino brought the stock to them.

Two days later it was still raining, but Padre Kino insisted on leaving. Before they had gone five miles, a violent hurricane began to blow. The horses stopped in their tracks. It was impossible to go on. They spent a miserable night in the open and Padre Kino's fever returned. His feet and legs were swollen with rheumatism and Manje wished with all his heart that they were back with the friendly natives of Bac.

In the morning Padre Kino insisted that they go on. After a few miles, however, one of the servants shouted and Manje saw the padre leaning over his saddle horn, almost unconscious. By the time they got him off his horse, he had fainted. Hastily the Indians made camp and all that day Kino tossed on his blankets, nauseated, |133| fevered, his poor legs swollen so he could not find comfort in any position.

The next day he managed to swallow some medicine and keep it down; the pains left him and the swelling decreased. He was able to mount his horse and continue the journey. The river was too high to cross and they continued along the west bank until they came to a large village. The Indians brought over a sheep, butchered it and made some broth.

"He is so sick, so weak!" said one of them, looking sorrowfully down at Kino.

Manje frowned. Padre Kino was too ill to travel, but he could not stay out in the open. They pressed on, arriving at Dolores on the 14th of March. As they went into the church to thank God for bringing them safely back, no one was more grateful than Captain Manje. Yet no one looked forward with more eagerness than he to a second northwest expedition. Like Kino, he remembered only the good.

While Captain Manje was making his official report, Padre Kino was writing long letters to everyone he knew. At some time during that desperate ride from the Gila River, he had become convinced that in spite of Manje's objections, his own long-ago idea concerning |134| California was the true one. It was not an island. It was a peninsula!

He took the big blue abalone shells from the packs and compared them to the one he had brought from the west coast of California. Bigger than a man's hand, heavy, with a dark blue coating on the outside, and inside iridescent shades of brilliant blue and green winking up at him. They were the same. There was no doubt of it. These new ones must have been brought from the Pacific Coast by the strange white men the Yumas and Pimas had described to him.

California was a peninsula, he could supply Salvatierra and his missions by driving stock around the head of the Sea. He must write Salvatierra at once. And he must tell the men of Caborca to stop work on the boat. It was no longer needed.

But before that letter was written, a messenger arrived with an amazing communication from Salvatierra. He had not heard from Kino for months, but the two of them had reached the same conclusion at almost the same time.

"We are desirous of knowing," wrote Salvatierra, "whether from that new coast which Your Reverence traversed, California may be seen and what sign there is on that side whether this narrow sea is landlocked!"