Finding The Chapel

Kino Grave Discovery

Page 2

To download "Archaeology Notes on the Discovery of Father Eusebio Kino" written by Dr. William W. Wasley in 1966, Click Archaeology Notes on Discovery of Kino by Wasley

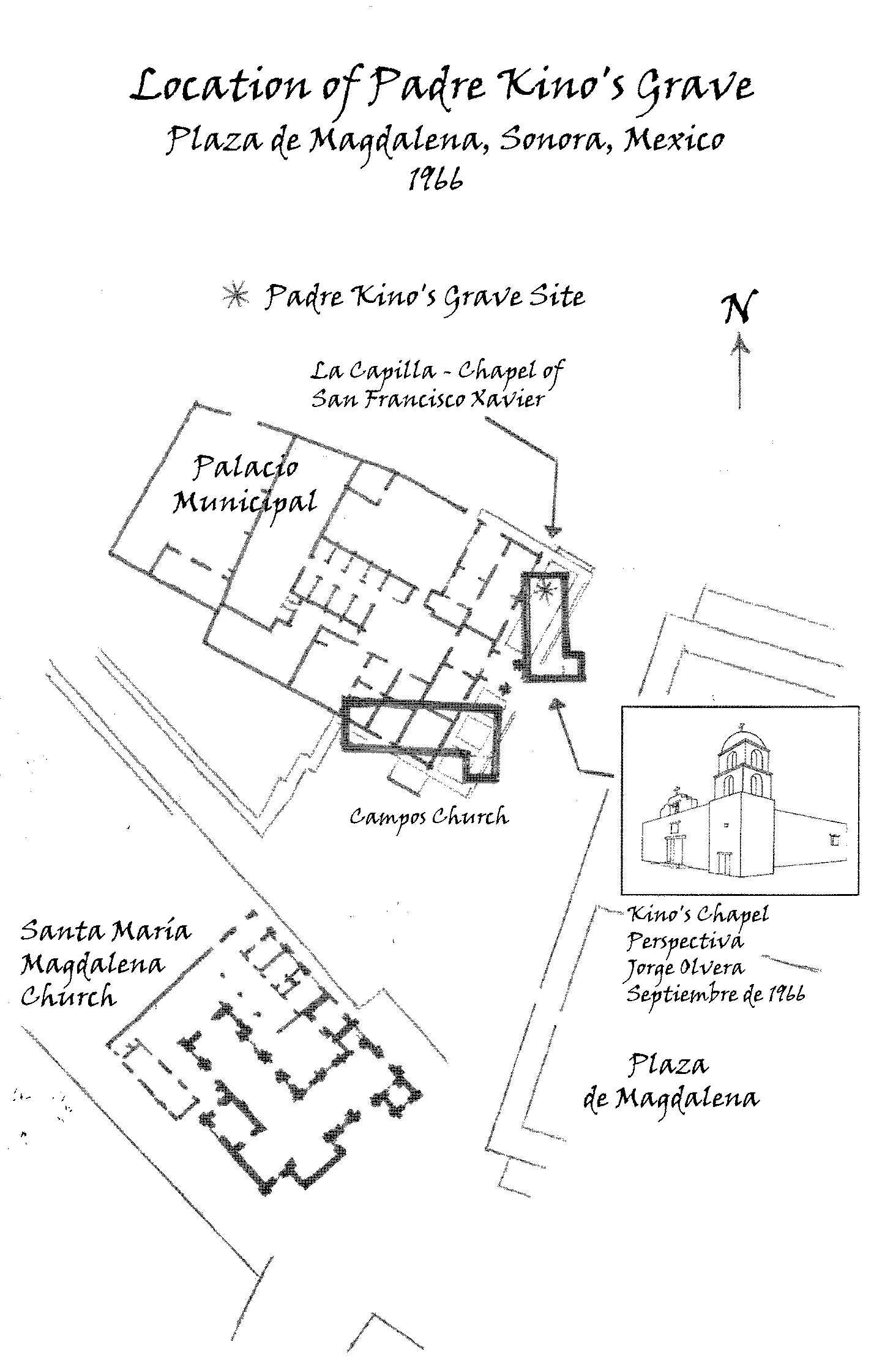

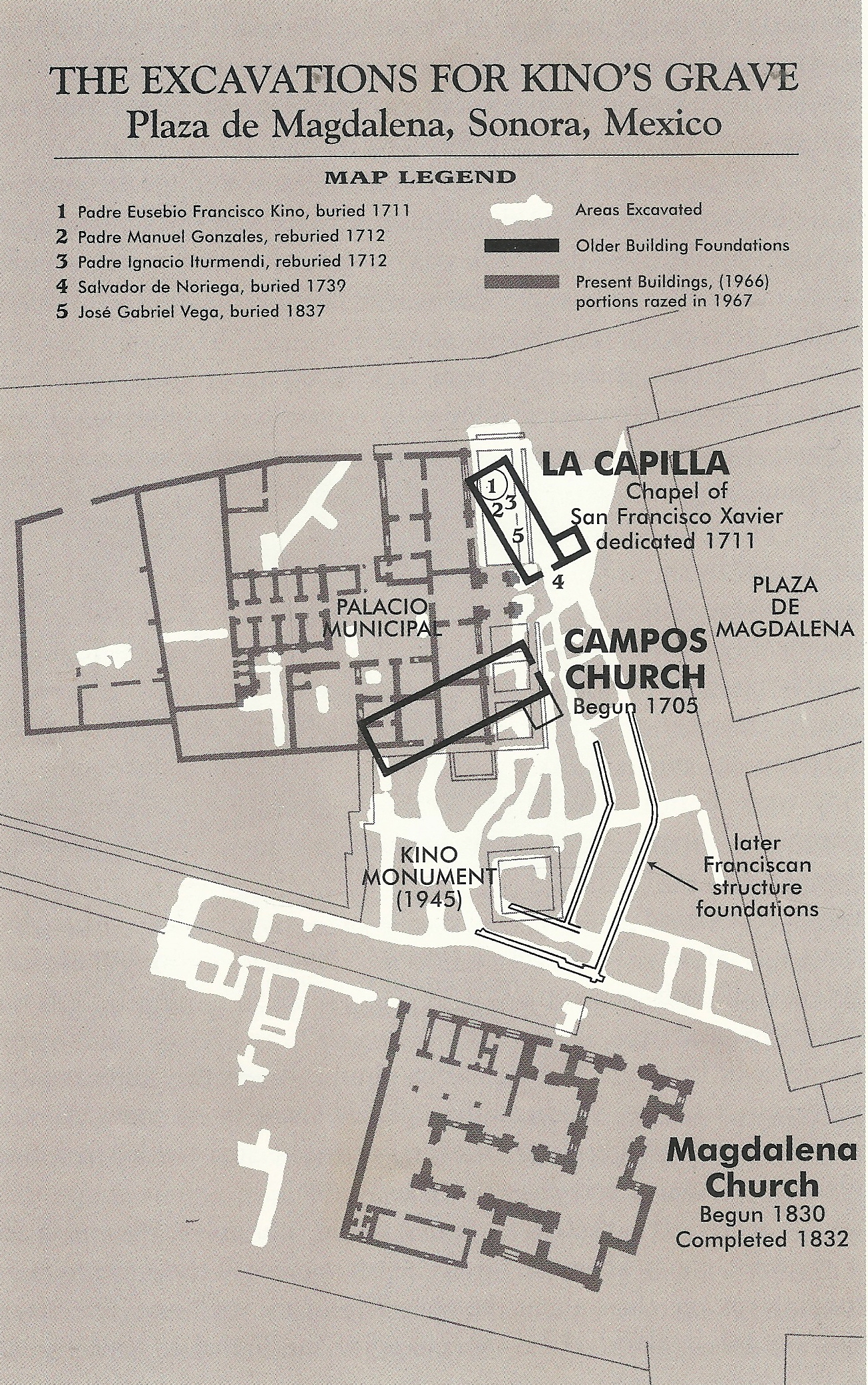

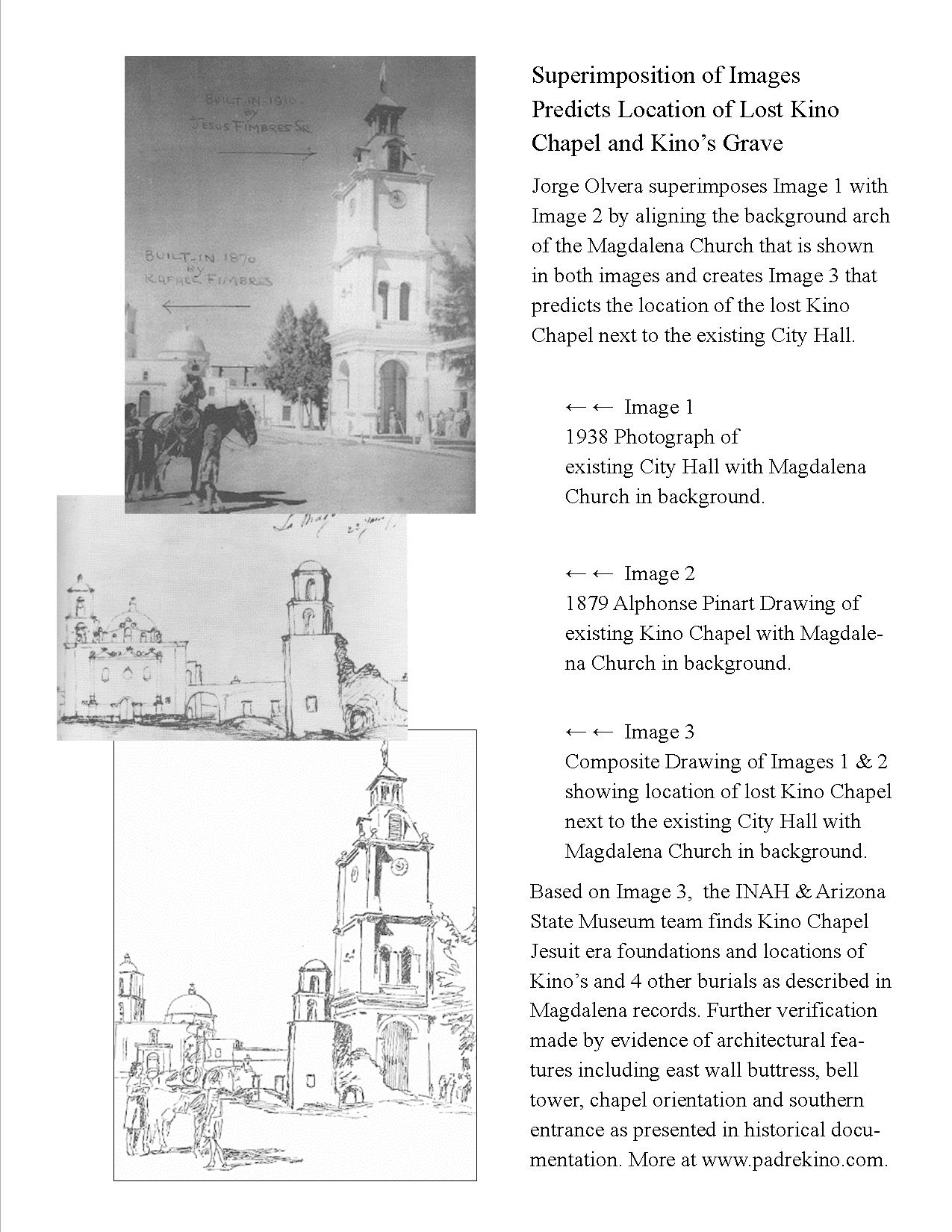

Existing buildings shown: Magdalena Church ("Santa Maria Magdalena Church") (built 1832 and is the present parish church ) and City Hall ("Palacio Muncipal") (built 1910 and demolished to build Kino Masoleum and Square in 1970); Non-Exisitng buildings shown with foundation locations: Campos Church (built 1706 and destruction date unknown) and Kino Chapel ("La Capilla" and "Chapel of San Francisco Xavier") (built 1711 and destroyed completely in earthquake of 1887). Common view point for Image 1 and Image 2 near north direction arrow symbol.

Composite Sketch Tracing of 1938 Photo (Image 2)

overlayed by 1879 Pinart Drawing (Image 3)

Reveals Location of Kino Chapel Foundations

Within Inches of City Hall Clock Tower

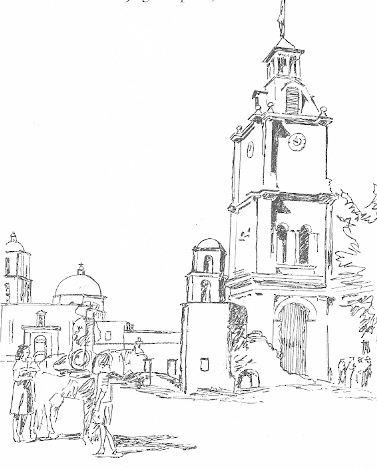

The below photograph (Image 2) shows part of the facade of the present Magdalena Church as well as the clock tower of the City Hall. The ruin of the Kino Church no longer existed at the time of the picture was taken.

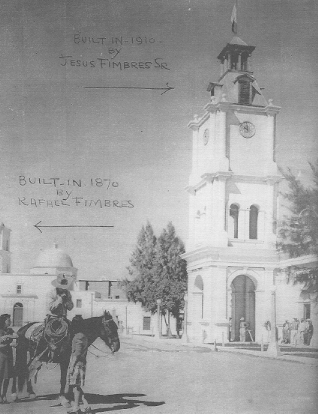

Amazingly, the photograph (Image 2) had been taken almost from same vantage spot or viewing place and with the same angle where Pinart had situated himself when he made his drawing (Image 3) of the present Magdalena Church and the ruin of the Kino Chapel (small tower immediately to left of clock tower). Same view point for Image 1 and Image 2 is approximately near the north direction arrow symbol in the map above.

Dr. Jorge Olvera used tracing paper and superimposed Image 2 on Image 3 using the same architectual registration points that match up in both Image 1 and Image 2 on the facade of the buildings to the right of the front entrance of the Magdalena Church that is in the background of both images.The Composite Sketch (Image 1) of the two images worked perfectly and based on the Composite Sketch Dr. Olvera predicted where Kino''s grave site would be found - right next to the clock tower of the City Hall and near its northeast corner. Dr. Olvera used architectural archeology to predict the location of the Kino Chapel.

The Composite Sketch was made 5 days before Kino''s skeletal remains were first discovered and just as the Mexican Federal Government was to stop funding.

Image 2

Post 1938 Photograph by Unknown Photographer

The clock tower of the City Hall is on the right and the Magdalena Church is on the left in the background with enclosed arch that was used as a common architectural registration point also found in Image 3.

The ruins of Kino''s Chapel with bell tower is on the right and the present Magdalena Church is on left in the background with building with arch that was enclosed at the time the photograph above (Image 2) was taken but could still be used as a common architectural registration point.

Image 3

1879 Alphonse Pinart's Drawing

The ruins of Kino's Chapel with bell tower is on the right and the present Magdalena Church is on left in the background with building with arch that was enclosed at the time the photograph above (Image 2) was taken but could still be used as a common architectural registration point.

Image 4

1864 J. Ross Browne Drawing

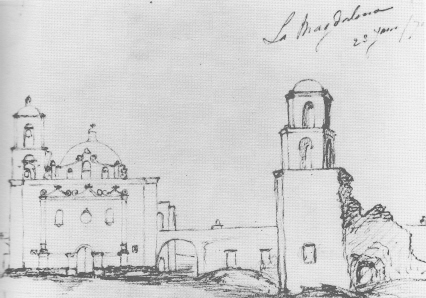

Extensive excavations away from the City Hall of approximately 1.2 miles in length were made over a 2 month period. This was due in part by the mistaken interpretation of the system of perspective used in the Browne Drawing (Image 4) by the Project Leader, Dr. Olvera's superior. The Project Leader believed that the Browne Drawing was made from a single point of view with a single vanishing point and that buildings between the Magdalena Church and the Campos Church in the Browne Drawing continued to be aligned with the facade of the present Magdalena Church towards the northwest. The Kino Chapel is not depicted in the Browne Drawing. Also the Project Leader mistakenly believed that the structure with the tower in the Pinart drawing (Image 3) was the Campos Church and not the Kino Chapel. He did not the accept the analysis revealed in the Composite Sketch (Image 1). After the arrival and advocacy of physical anthropologist Dr. Romano from INAH did the Project Leader allowed Dr. Olvera and Dr. William Wasley of the Arizona State Museum to dig trenches that revealed foundations that ran towards the City Hall.

Dr. Olvera's correctly interpreted the Browne Drawing at the start of the excavations. He saw that the Browne Drawing used two different vanishing points in its system of perspective. The buildings between the Magdalena Church and the Campos Church actually moved away from the facade of the Magdalena Church in a perpendicular fashion in a due northwesterly direction toward the City Hall. This interpretation along with Dr. Olvera''s historical analysis of the architecture in the Pinart drawing (Image 3).revealed the location of the Kino Chapel and its buried foundations.

Further documentary evidence confirmed the location of the Kino Chapel. Fernando Grande's 1828 report described the north south orientation of the Kino Chapel with its entrance in the south wall. Fr. Perez Llera's 1828 report of construction of butress to on of the chapel walls that was in danger of collaspe. The Kino Jesuit era building foundations and walls were made from very different materials than the later Franciscan foundations and walls. . All these architectural components were confirmed by the team's excavations.

Once the Kino Chapel was found Kino's skeletal remains were located within the Chapel by the evidence described in the burial records. Click Grave Discovery.

For excerpts from Jorge Olvera account of the discovery of Kino's Remains in "Finding Father Kino: The Discovery of the Remains of Father Euesbio Francisco Kino 1965-1966"

Click,

Grave Discovery Olvera Account Page

Discussion on perspective and double vanishing points of Browne drawing on pages 80 - 82 of Finding Father Kino

.

More Detailed Map Showing Kino's Grave Site

Foundations of Kino Era Structures Shown in Solid Black

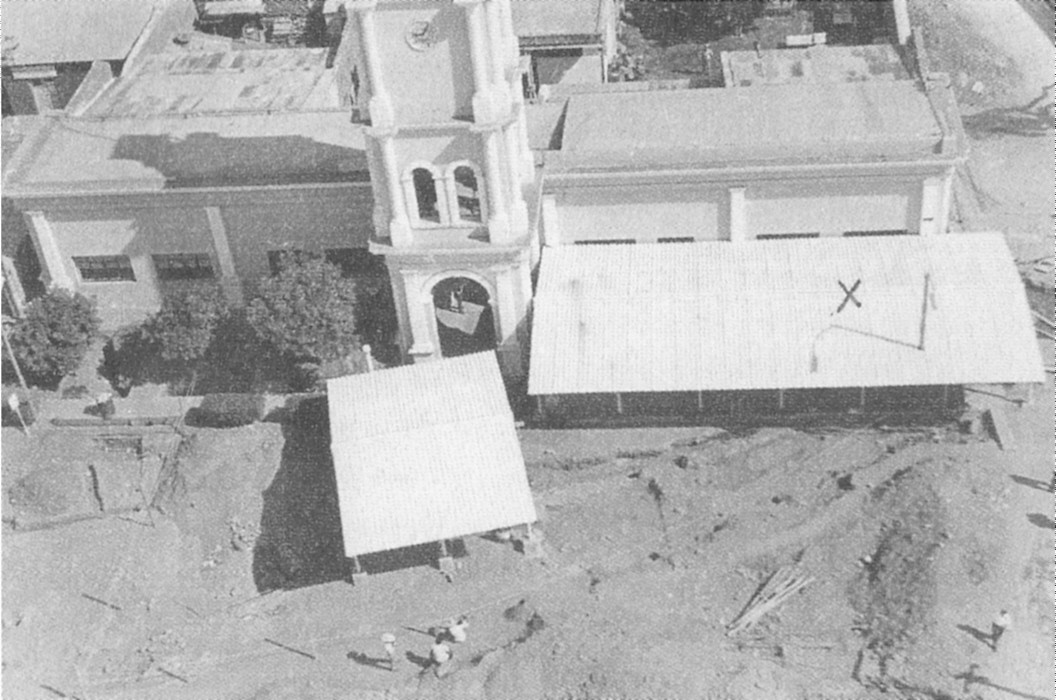

A 1966 aerial view looking west over Magdalena de Kino, Sonora after the discovery of Kino''s grave site and before construction of the new plaza in 1970. The letters mark locations: A: Old Kino monument. B: Magdalena Church C: Palacio Municipal (City Hall) with clock tower. D: Vacant lot. E: Jail. F: Rio Magdalena. G: Tent over northwest segment of the Kino Chapel with Kino''s remains. H: Tent over southeast segment of Kino Chapel with remains of Salvador de Noriega. I: Railroad tracks of the Ferrocarril del Pacifico. J: Magdalena Church office. Its entryway was part of the old arch that Olvera used as an architectural registration point for his Composite Sketch (Image 1) The location of letter J is seen between Location B and the words "Calle Francisco I. Madero."

Location of Kino's Grave Site under Temporary Ramada

Marked by "X" Next to Magdalena City Hall

Summary of Finding Father Kino

Dr. Bernard L. Fontana

On February 14, 1965, on the fifty-third anniversary of Arizona's admission to the union as a state, a larger-than-life-size bronze statue of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino was dedicated and presented as the last of Arizona's two representatives in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol. (The other is a statue of copper magnate John C. Greenway). Among the distinguished guests at the unveiling and dedication ceremony was the Honorable Hugo Margin, ambassador from Mexico. It was possibly the ambassador who alerted Mexican President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz that Americans were paying singular homage to a man who belonged as much to Sonora and Mexico as he did to Arizona and the United States.

Soon after, President Díaz Ordaz charged his Secretary of Public Education, Agustin Yáñez, with the task of locating and positively identifying Father Kino's mortal remains, a job which the secretary assigned on June 30 to Professor Wigberto Jiménez Moreno, head of the Department of Historical Research of Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Beginning in August 1965, a half year after the statue's dedication, an international team of investigators headed by Jiménez Moreno arrived in Magdalena, where it was known Father Kino had died in 1711, to begin the search on the ground. It was a hunt that had gone on sporadically at least since 1922 when Bishop Juan Navarette tried without success to locate the grave site.

In addition to Jiménez Moreno, the principal investigators were Jorge Olvera H., an art and architecture historian with a background in archaeology; Arturo Romano P., physical anthropologist; Jorge Angula, archaeologist; Sonoran historians Fernando Pesqueira and Father Cruz Acuña; cartographer Conrado Gallegos; chemist Gabriel Sánchez de la Vega; and Americans William W. Wasley, archaeologist, and Father Kieran R. McCarty, O.F.M., historian.

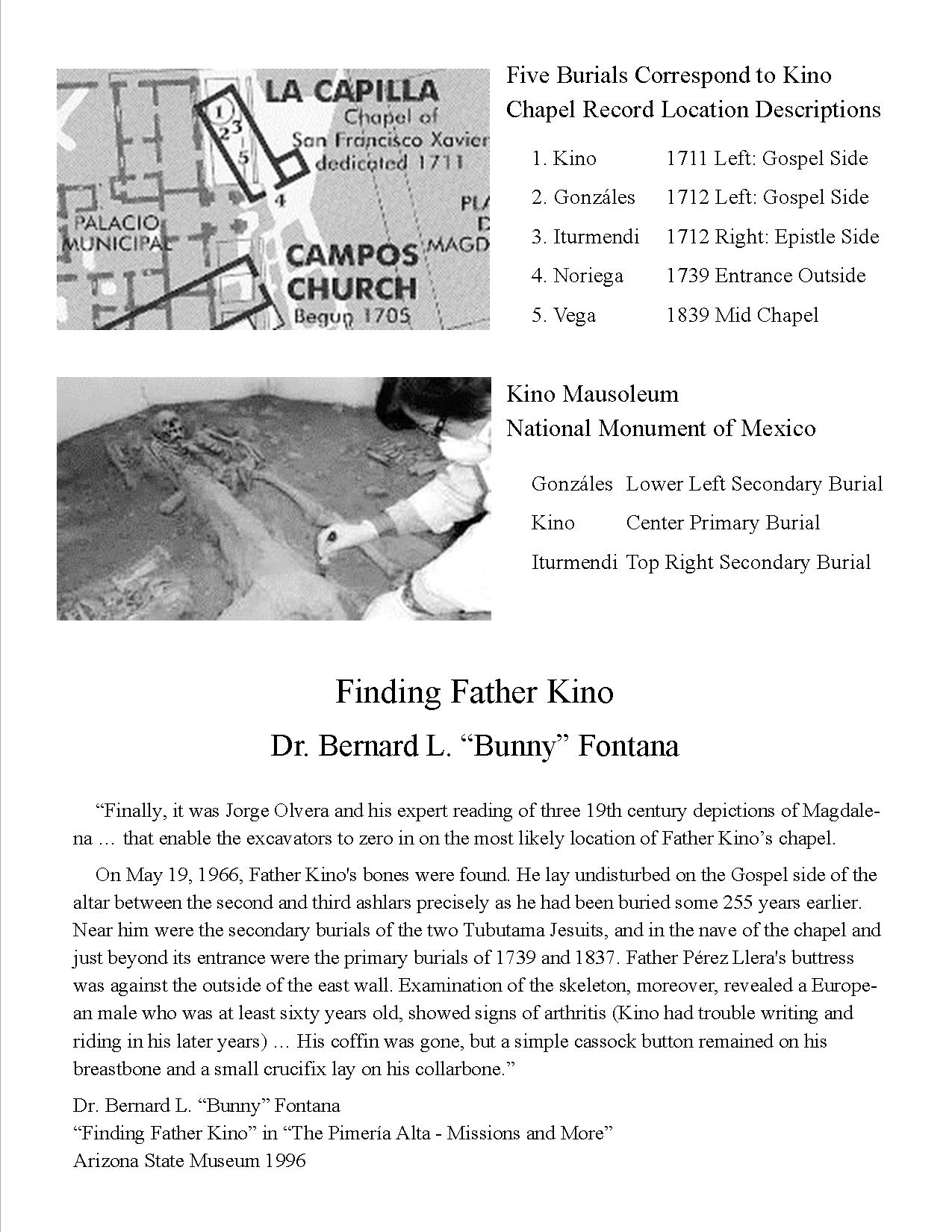

As work proceeded, it became known from documentary and published sources that Father Kino had died at the age of sixty-five on the night of March 15, 1711, and had been buried on the Gospel side of the altar between the second and third ashlars (foundation stones) in the new chapel he had just dedicated to San Francisco Xavier. It was also learned that the year after Kino's death two other Jesuits were exhumed from their original burial places in Tubutama and their bones, in a jumble, were reburied on the Epistle and Gospel sides of the church. In 1739, Spaniard Salvador de Noriega was buried at the entrance to the chapel. and in 1837, José Gabriel Vega was buried beneath the nave. In 1828, Father José Pérez Llera had put a stone buttress next to part of the slumping east wall of the chapel.

As work in archives and libraries proceeded, so did work in the field. Members of the team looked carefully at the construction materials and techniques used at the ruins of Remedios, a church known to have been built by Father Kino. So did they examine the adobe walls and stone foundations at Cocospera and carry out excavations in Magdalena in places where earlier excavations had occurred, and where their own sense of the unfolding evidence took them.

Finally, it was Jorge Olvera and his expert reading of three nineteenth-century depictions of Magdalena - those by John Russell Bartlett (1852), John Ross Browne (1864), and Alphonse Pinart (1879) - that enabled the excavators to zero in on the most likely location of Father Kino's chapel. These drawings indicated the location of Father Agustín Campos's 1705 church in relation to the 1832 church of Father Pérez Llera (the one presently in use), and to Father Kino's chapel. The location of the latter proved to be in an area immediately next to the city hall.

On May 19, 1966, Father Kino's bones were found. He lay undisturbed on the Gospel side of the altar between the second and third ashlars precisely as he had been buried some 255 years earlier. Near him were the secondary burials of the two Tubutama Jesuits, and in the nave of the chapel and just beyond its entrance were the primary burials of 1739 and 1837. Father Pérez Llera's buttress was against the outside of the east wall. Examination of the skeleton, moreover, revealed a European male who was at least sixty years old, showed signs of arthritis (Kino had trouble writing and riding in his later years), and who, unmentioned in the documents, had lost two central incisors long before he died (the tooth sockets had grown over). His coffin was gone, but a simple cassock button remained on his breastbone and a small crucifix lay on his collarbone.

The discovery of Father Kino's remains transformed Magdalena. Its name is now officially Magdalena de Kino and the archaeological remains of Father Campos's early eighteenth-century church, was completely redesigned by architect Francisco Artigus and rebuilt in 1970 and 1971 as the beautiful memorial plaza seen there today.

Bernard L. Fontana

"Finding Father Kino"

"The Pimería Alta - Missions and More" 1996

To download the summary of the Finding Father Kino account written by Dr.Bernard L. Fontana in 1996, Click Finding Father Kino Fontana.

Archeological Notes On The Discovery Of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino

By William W. Wasley

In the initial stages of our search in Magdalena Sonora, for the remains of Father Kino, we had only two leads on which to base our hopes: some meagre documentary evidence little of which eventually turned out to be misleading, and what little we knew about the architecture of the colonial period in the Pimeria Alta of northern Sonora and southern Arizona. In the final months and weeks of our investigations the relevant documentary evidence was to increase nearly tenfold and provided the archaeologists with valid interpretations of the structures they were uncovering, Long before this point was reached however, the archaeologists had uncovered dozens of foundations beneath the streets of Magdalena, adjacent to the present church, and even in the jail yard.

At first these remnants of earlier structures served only to confuse the basic archaeological problem and prompted project leader Prof. Wigberto Jimenez Moreno to comment as follows at the end of the project: Our search had been "like looking for a needle in a haystack, but first we had to find the haystack!" There was little hope of finding or identifying Father Kino unless we could first find and positively identify the chapel in which Kino had been buried, This, in a nut shell, was our [Wasley 2] basic archeological problem: it cannot be more simply stated. Yet at times the solution appeared elusive if not impossible.

As an example, it had occurred to us that the chapel of San Francisco Javier might have been built upon slightly higher ground than that of the surrounding area, and that in the late 1800' s when some of the modern structures area built in the vicinity of the present plaza, this area might have been levelled, leaving no trace at all even of the foundations of the earlier chapel. This unwelcome thought continued to haunt us from time to time.

Nevertheless, an intensive search was mandatory, and we needed to undertake as much excavation as possible in the general area, in order to eliminate as much ground and as many structures as possible. This approach to the problem, the step by step elimination in order to zero in on the true location of the chapel, was dictated by Prof. Jimenez Moreno. It was an excellent idea. It involved more time and expense, but it paid off in dividends. Most of the other foundations that we encountered-—if not all of them——could be identified historically with Franciscan and post—Franciscan structures. At least we were eliminating on the one hand, and learning more and more about post-Jesuit period foundations and architecture on the other.

For instance, there was a strong feeling among some of the local people that the chapel in Calle Pesqueira, several hundred meters southwest of the present church, was indeed the [Wasley 3] chapel of San Francisco Javier in which Kino had been buried. Excavations underneath the floor revealed three previous excavations—where someone had searched before-—and nothing else except a potpourri of artifacts, all post-Kino in time, including a bicycle chain and a cigarette lighter, These 1 saw in 1963 during the Lion's Club excavations here, and on the basis of what I saw then, everything was too late in time to have belonged to the Kino period. Virtually everything was 19th century or later. Two years later Prof. Jorge Olvera examined this site and on the basis of the architectural style alone was able to determine that the structure belonged to the Franciscan period. A few months later Father Kieran McCarty came across a document from the archives of the Franciscan Colegio de Santa Cruz de Queretaro stating that this chapel had in fact been constructed by the Franciscan Father Ruiz in 1815. Clearly, this could not have been the chapel in which Kino was buried.

One thing that I was becoming more and more convinced about as the excavations progressed was that in the Pimeria Alta there was a basic difference between the foundations of major structures of the Franciscan period and later as opposed to those of the earlier Jesuit period. Throughout the colonial period foundations consisted of boulders set in mortar in a shallow trench. However, the mortars used were usually very different in the Jesuit period in the later periods. During the Franciscan period the boulder foundations were set in a lime mortar, which to this day still remains quite [Wasley 4 ] hard. The Jesuit boulder foundations of the Kino period, as I had earlier observed at the mission ruins of Los Santos Angeles de Remedios, were set in a very clayey mortar (more clay—like than the mortar used in cementing unfired adobes or than the consistency of the adobes themselves. This feature had also been observed in the later Jesuit mission structure of Guevavi in southern Arizona. Throughout the colonial period, however, some boulder foundations were set in a regular adobe mortar, although the Jesuits never used a lime mortar in Pimeria Alta and the Franciscans apparently did not use the soquete mortar.

This overlap in the use of adobe mortar foundation construction sometimes does not pose a serious problem in identification because in wall construction the Franciscans frequently used fired brick, and in Pimeria Alta, at least, the Jesuits apparently never did. Even if only adobe foundations are found in place, the presence of fired brick in the surrounding debris or incorporated in the foundations themselves is usually a sure sign that the construction, or at least the reconstruction of a structure, was made during the Franciscan period. This observation tends to hold true as a rule, except in places like Magdalena where there is so much mixture of fill, artifacts, and building materials over the central portion of the town that it would not be impossible to find fired brick fragments in the fill and vicinity of the chapel of San Francisco Javier even if it had never been reconstructed or repaired with fired brick by the Franciscans. In fact, exactly thig did happen during our search, and this is why so much evidence was needed [Wasley 5] before we could be really sure what structures we were dealing with.

On May 13, 1966, we begun to encounter in our excavations a new set of foundations. It soon became apparent that these were of the boulder and clay mortar (soquete) type which I felt belonged to the early Jesuit period. I suggested that several of us take a trip to Remedios to verify that this was the same type of foundation as used by Father Kino in the construction of that church. Prof, Jimenez Moreno agreed to this, and on May 15th, Prof. Arturo Romano, Prof. Jorge Olvera, and I along with two laborers went to Remedios.

The mission of Los Santos Angeles de Remedios about 45 Kms. by road northeast of Magdalena, was founded by Father Kino. He began construction of the church in 1695 and dedicated it in January, 1704. It is the only church built by Father Kino, to my knowledge, that was not subsequently rebuilt or built upon. Secondly, I also knew that one end of this church extends over edge of the mesa on which it was built, so that with a minimum of excavation it would be possible to clear away enough dirt in an hour or two to expose enough of the foundation to be able to examine the precise nature of its construction. What we found was exactly the same type of construction, river boulders set in soquete mortar, that we had just uncovered in Magdalena, Back we went, only to find that in our absence Prof. Jimenez Moreno had found a second set of similar foundations that same day. While we were not exactly elated with this news at first, it soon became [Wasley 6] apparent that we were probably faced with trying to determine which of these two structures (if either) was the finished chapel in which Father Kino had been buried and which (if the Agustin other) was the church that Father Augustin Campos had already started at the time of Kino's death, This was the real challenge, for finally we felt certain that we were working with Kino period structures. We felt that we might be getting close to the solution, but we still needed proof as to which structure, if either, was the chapel dedicated to San Francisco Javier in which Father Kino had been buried.

While all of this prowling around for walls and foundations had been going on in the dusty streets of Magdalena, the historical researchers had been prowling through dusty archives searching for——and finding——more documentary evidence that should help provide a positive identification of the chapel. Their data began pouring in to us almost faster than we could dig.

The amazing finds were these:

1) The historical researchers found documentary evidence that the Jesuit missionary Father Gaspar Stiger, a German, had buried a Salvador de Noriega, in life employed by Lorenzo Velasco, just outside the door of the chapel of San Francisco Javier in Santa Magdalena, in August} of 1739. The archaeological crew uncovered a burial in just such a spot with reference to one of the Jesuit period structures.

2) The historical researchers revealed that in 1828 [Wasley 7] the inspector Fernando Grande had stated--for the first time in all of the historical records that we know about——that the chapel faced to the south ("al medio diet" ) and that it had a small tower. It was not long after this that the archaeologists were able to determine from the foundations that this same structure did face to the south. It was much later, however, at the very end of the project and actually during the process of winding everything up that Prof. Jorge Olvera finally found the foundations of the tower.

3) In this same document the historians were able to ascertain that the image of San Francisco Javier had been moved from the altar to about the midpoint of the nave of the chapel by 1828. The reason for this, we have to assume, was that the Fiesta de San Francisco Javier, celebrated annually and currently reaching an influx into Magdalena every year of an additional 10,000 people, had reached impossible proportions 140 years earlier in the tiny chapel, and the image had been moved to provide better traffic circulation through the chapel. In 1837, the historical documents reveal, an elderly man of 90 years died and was buried inside the chapel in front of the niche of Jan Francisco Javier. The archaeologists found, at one side of the structure, about half way the length of it, the burial of an old man with his feet towards the far side of the nave. The historical documents would seem to provide the identity of the burial, while the position of the burial would indicate that the image of San Francisco Javier, at the time that it was moved from the altar, had been [Wasley 8] installed on the west side of the nave.

4) The historical researchers found documentation to the effect that Father Perez Llera was about to build a buttress to support one of the walls of the chapel. The buttress must have been built, because we found one outside the east side of the chapel. It was the only one we encountered.

There were a few other points of historical evidence, minor in terms of what we really needed, to indicate that this structure was indeed the chapel of San Francisco Javier in which Father Kino was buried. One of these was ruins of the the sketch of the chapel made by the historical buff, Alfonse Pinart, in 1879.

In terms of the archaeological—historical data, we had still to find Father Kino's remains flanked on either side by the re-interments of Father Gonzalez on Kino's right and Father Iturmendi on his left, with Kino on the gospel side with his head towards the altar. Actually, by this time, we had found the primary burial (that of Father Kino) with its head towards the altar, and we had found the two secondary burials. I still wanted to determine that Father Kino was in fact on the gospel side of the chapel. In order to do this, and in order to tie up several other loose points, it was necessary to continue excavations in order to find the west wall of the chapel. This endeavor was only moderately successful. We did find enough of the west wall to be able to determine that the primary burial, that of a priest on the basis of its orientation was also buried on the gospel side of the chapel as Kino had been. However, the fragmentary condition of this wall allowed us to accomplish little else beyond determining the width of the chapel and the fact that a later burial had been intruded into the foundation, we were not able to find the west side of the door.

Although the archaeological evidence, supported to a considerable extent by historical documentation, has conclusively demonstrated that the remains of Father Eusebio

Francisco Kino have been found, neither archaeology nor history by themselves could have established this fact. On the other hand, the physical evidence of the burial itself (including orientation, the coffin, and the crucifix on the left clavicle) and the physical anthropological characteristics as interpreted as the skeleton by Prof. Arturo Romano would alone have established the fact that this was Father Kino. In other words, the nature of the burial establishes it as belonging to a priest or missionary, while the physical characteristics of the skeleton establishes it as belonging to a European of Alpine stock. As far as I have been able to determine no other priest of European ancestry and Alpine stock was ever buried in Magdalena.

Is there anything else from an archaeological point of view that should be done in the future to clarify more of the segment of history that deals with the final resting place of Father Kino? There is, from when the present Ayuntamiento structure is razed to permit the construction of an appropriate monument to Father Kino, there is a good chance of finding though [Wasley 10] archaeological exploration one or more of these four things : 1) more of the west wall of the chapel; 2) the room(s) (one or two) that comprised Father Campos' quarters in which Father Kino died; 3 ) the quarters that Father Font used in 1776; and 4) a possible sacristy adjunct of the chapel.

Archeological Notes On The Discovery Of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino

By William W. Wasley

To download "Archaeology Notes on the Discovery of Father Eusebio Kino" written by Dr. William W. Wasley in 1966, Click Archaeology Notes on Discovery of Kino by Wasley

To Download

"Finding Father Kino's Grave Summary"

Two Page Flyer

Finding Father Kino's Grave - Two Page Summary Flyer

To Go To Kino Grave Discovery Site History (page1), click

Grave Discovery Site History Page

To Go Kino Grave Discovery Olvera Account (page 3), click

Grave Discovery Olvera Account Page