Kino - California Builder

Kino - Founder and Builder of Antigua California

Harry Crosby

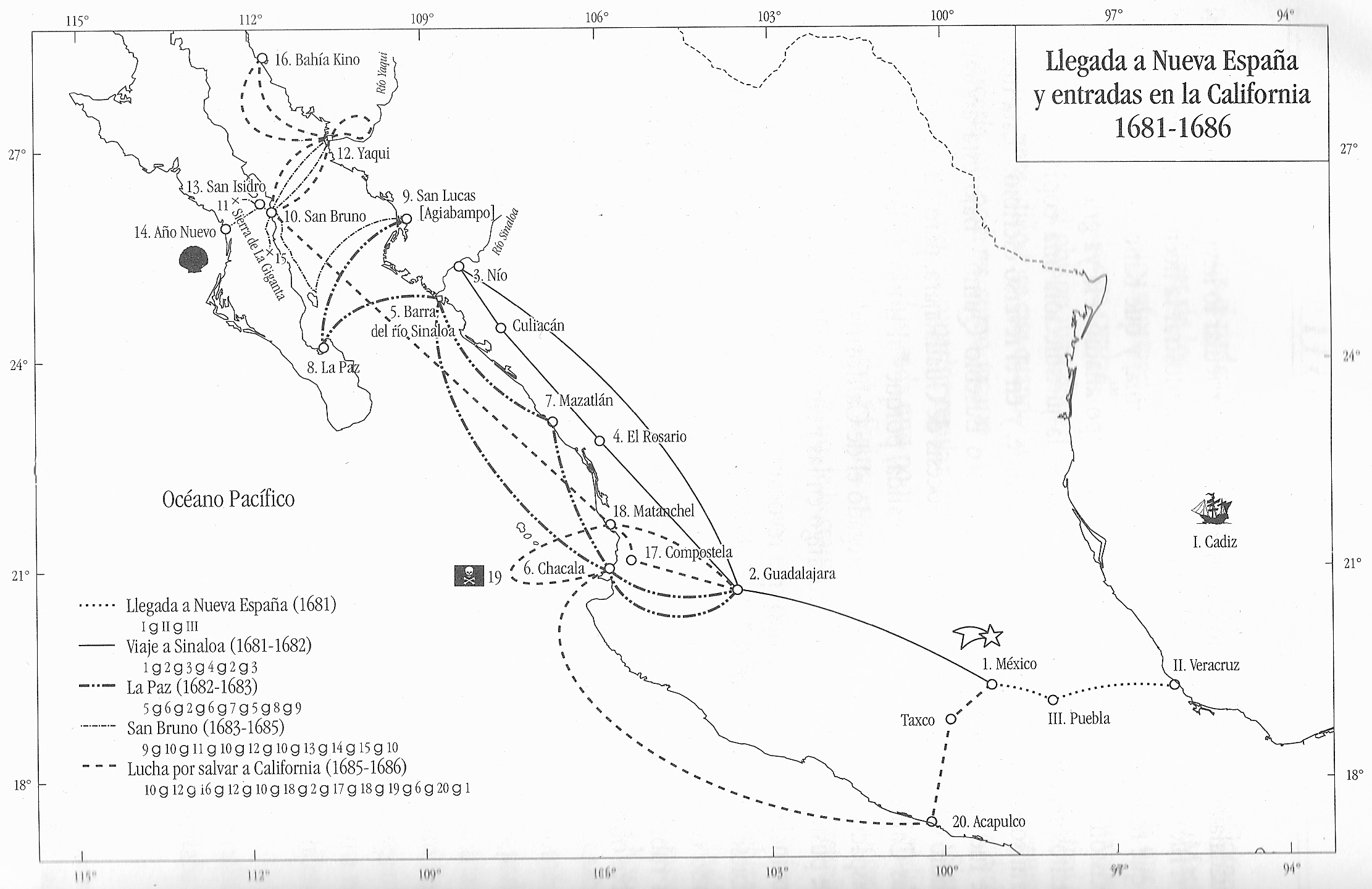

Map of Kino's Mexican Mainland, California and Pacific Ocean Trips

Before Kino's Assignment to the Pimería Alta

To View Legend, click Llegada Map Legend document (pdf)

Kino in California

In late 1681, Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino, [19] a Jesuit just arrived in New Spain, was assigned as geographer and mapmaker as well as missionary in a costly, government-backed effort to evaluate and colonize the California peninsula. From 1683 to 1685, "Almirante" (Admiral) Isidro de Atondo y Antillón led a group of soldiers, sailors, servants, colonists, and missionaries who tried to establish themselves, first at the harbor of La Paz and then at a site they called San Bruno on the mid-peninsular gulf coast. However, the expedition suffered <8> from an accumulation of problems and was withdrawn to a mainland port to regroup. Before it could be outfitted for a return, Spain experienced one of its periodic financial crises and the monies for California were preempted for more pressing imperial needs. Almirante Atondo had spent nearly a quarter of a million pesos and he blamed the new land's sterility and lack of usable resources for much of the cost. He helped to create a perception of California that dealt a severe blow not only to the continuation of his own venture, but also to the prospects of anyone who might later try to raise money for an occupation of the peninsula. After royal funding was withdrawn from the Atondo-Kino operation, the Society of Jesus declined to finance the activities that would be needed to reopen and sustain their suspended mission. [20] For the time, California was abandoned by all Spanish interests.

While Kino was with Atondo, necessity forced him on two occasions to leave the peninsula, sail to Sonora, and beg for large quantities of food at the Yaqui missions. [21] After his California mission was suspended and during the time he was waiting to return to it, Kino became convinced that a Jesuit California would need to have a close relationship with its prosperous sister missions across the gulf. Even the royal decision to abandon California did not end Kino's aspirations. When he received the news, he immediately wrote to his provincial to ask to be sent to the missions of Sonora; they were closest to California and from them he could pursue his return to the peninsula. When he was installed in Sonora, Kino wrote to a legal advisor of the Council of the Indies in Madrid to point out the prosperity of Sonora's missions and to ask for permission to plan a California campaign which those missions would help to supply. [22]

Kino sustained an active correspondence with benefactors to stimulate support for his ideas. [23] He initiated a campaign of letters and personal visits to fellow Jesuits in northwest New Spain. As a result, Padre Francisco María Piccolo, a missionary in the Tarahumara, became the first to petition the Jesuit general for a post with Kino in California. [24] As years passed, Kino regularly interrupted his routine missionary chores to carry out explorations that led ever closer to the head of the Gulf of California and a possible land route to the peninsula. Even as he established new missions among the Pimas, he initiated cattle herds that might some day assist a Jesuit expansion to California.

Kino and Salvatierra Plan Return of Jesuits to California

In midwinter of 1691, in the heart of the Sonoran desert, a pair of Italian missionaries rode from mission to mission. Far into each night on the trail, they sat before hardwood campfires and planned a religious conquest in the name of their chosen patroness, Our Lady of Loreto. [25] One of these men was Eusebio Francisco Kino. His companion was Padre Juan María de Salvatierra, recently appointed to be "visitador general," the inspector of all Jesuit missions in northwest New Spain. [26] Despite the posts these men held, neither New Spain nor <10> the Pimería occupied their minds. A California crusade was being born. Six years after his agonizing withdrawal from that storied land, Kino was enlisting for a new campaign. [27]

Eusebio Kino was already a considerable figure in the greater world. He had published research in the field of astronomy. He was respected for his role in Atondo's aborted California effort. His letters to influential people had stirred new interest in the mainland missionary frontier and the fabled "island" lying beyond. His subsequent labors were well on their way toward establishing an extensive network of missions in the Pimería Alta; yet Kino was restless. He had not willingly substituted service at mainland missions for the pursuit of his California dreams. He saw the two areas as a continuum, with rich Sonora provided by God to support the spiritual conquest of poor California. [29] Kino's determination was galvanized by the enthusiasm of his visitor general. Throughout Salvatierra's official visit to the Pimería, the two refined a plan to go together to take the prize that lay across the Sea of Cortés. [30] >

All considered, Kino and his fellow Jesuits could not fault the admiral's decision to withdraw from California. They blamed the failure primarily on soldiers and colonists, but they also realized that the practical side of the religious effort had been inadequately prepared. In order to survive, a mission would need more capital, a better supply organization, and a nearby source of food. Kino hammered these points home - as well as his conviction that Sonoran missions could be tapped for much material aid. [32]

Salvatierra and Kino were convinced that they could gain and hold the proper influence over neophyte Christians if they could achieve two goals. First, they needed effective control over the soldiers required to secure the desired territory. [36] Second, they needed permission to exclude - colonists people that, in their minds, would have a disruptive and degrading influence on mission converts. ….

As Kino and Salvatierra mulled over their grand plans for California, they struck on the concept of a single authority in the field. They worked out details for a different sort of "conquista," religious to the core. The large, isolated Sonoran missions to the Yaqui and Mayo had provided them with more than an inkling of the advantages of relative independence. [37] but they aspired to more. In the fashion of the famous Jesuit institutions in Paraguay, their plan foresaw missionaries as the governors of an entire area and sole supervisors of all tasks required by both church and state. [38] They anticipated costs, problems of supply, and a host of other concerns. [39] When their arguments were thoroughly prepared, the two experienced missionaries felt ready for new careers in California. Salvatierra submitted a report of his Sonoran visitation to the provincial and added a letter in which he asked, as Padre Piccolo had done earlier, to be assigned to work with Kino for the religious conquest of California.

Although Padres Kino and Salvatierra were known and respected even in Europe, the provincial rejected the new proposal outright. He knew the bitterness of royal officials who had authorized the expenditures for Atondo's attempt <13 > to open California. The crown helped to fund all the existing Jesuit missions; the provincial refused to associate his order with requests for large sums of new money. Salvatierra then tried to go to the top; he appealed to the king and the Council of the Indies. When these letters were met with silence, the California conspirators realized that they would have to enlist broader support within both the Jesuit system and the government bureaucracy. [40]

The Advocacy Campaign

Individuals or organizations in the New World could sometimes sidestep their viceroys by dealing with their audiencias and, through that body, reach higher councils. If they had access to higher authorities or courtiers in Spain, so much the better. The Jesuits created an effective network of official and unofficial contacts with all levels of Spanish government and society, but before Salvatierra and Kino could exploit this asset, they had to overcome the resistance within their own order.

Individuals, even those as popular and respected as Kino and Salvatierra, could not simply declare their own crusades. [47] Any major undertaking had to be endorsed by a succession of superiors that ended with the general in Rome. Only with his support could a plan of such scope be brought before the civil government. [48] However, the hierarchy of the Society of Jesus remained conspicuously cool to the California proposal. The crown had been thoroughly disillusioned by the great amounts of royal money squandered on previous California ventures. [49] Jesuit leadership was understandably reluctant to associate itself with past failures and request additional outlays from a bankrupt royal treasury. [50]

Early in 1693, probably with help from influential friends, Salvatierra was made rector of the Jesuit college in Guadalajara. The energetic Jesuit found himself with more available time than he had had as a missionary and in a perfect position to promote interest in the California mission. Guadalajara was the seat of a bishopric, and its bishop, then Fray Felipe Galindo, had ecclesiastical authority over California and most of the intermediate lands. Salvatierra sought and received from Galindo the authority to administer the holy sacraments and to perform other ecclesiastical functions controlled by a bishop. [51]

The Audiencia of Guadalajara had civil jurisdiction over the peninsula and had previously taken a stand like that of the Council of the Indies, opposed to spending more royal funds in California where Atondo had seen so little promise. Nevertheless, members of this audiencia, and other members of the elite class in Nueva Galicia, were susceptible to any plan to develop an area over <15> which they had jurisdiction and from which they might derive profit by commerce or other means. They were all too aware of Guadalajara's secondary status after Mexico City, and they were always on the lookout for opportunities to develop business in their more remote and less-favored part of the Spanish world. A Jesuit mission would not lead directly to economic development, but it would be the necessary first step to establish the Spanish presence and open the peninsula to exploration. It was a simple task for the diplomatic Salvatierra to lobby effectively among Guadalajara's civil authorities and influential citizens. [52]

During 1696, Salvatierra sent a number of letters to Fiscal Miranda y Villayzán [attorney or member for audencia] to explain his arguments for returning to California. With these ideas, Miranda y Villayzán persuaded his reluctant colleagues that opening California would serve the economic interests of the province of Nueva Galicia. He also forwarded his position paper to the Conde de Galve, viceroy of New Spain since 1688. The audiencia withdrew its opposition and sent the viceroy a formal request to grant Salvatierra's petition. Although the viceroy rejected these appeals, the incident marked a notable change in the attitude of some civil authorities. [57]

Kino and Salvatierra expanded the scope and frequency of their correspondence within the Jesuit chain of command. Kino, in particular, had the ear of Padre Tirso González, the general in Rome, a sympathetic ex-missionary under whom he had studied in Sevilla. By 1695, the provincial in Mexico City, Padre Diego de Almonacir, not only felt the pressure of the missionaries' petition but also learned that it was supported by the general. [58] While Salvatierra sought backing among the Society's prominent benefactors, Kino enlisted the assistance of his fellow missionaries in Sonora and the Pimería Alta, some of whom began to accumulate herds and stores to contribute to California. [59]

Funding was the crucial factor in gaining approval from both the Jesuit hierarchy and royal officials. Part of the blueprint that Kino and Salvatierra < 16> drew up with so much care depended on freedom from the regulations and interference that would inevitably accompany funding that they did not control. To overcome that obstacle, Salvatierra and his advisors worked out an ingenious proposal. They recalled that back in 1671 Alonso Fernández de la Torre - a citizen of Compostela, a town on the road between Guadalajara and Sinaloa - left an endowment for the establishment of missions in Sinaloa and California. [60] Kino had used income from this bequest to finance his 1683 - 1685 efforts to establish a California mission. This gift from Fernández de la Torre gave the enthusiasts the idea of financing the entire venture through donations that would establish an adequate endowment. This solution would disarm the opposition. The viceroy would feel less like a watchdog for royal coffers. Jesuit leaders would not feel called upon to share money earmarked for other missions. Outside the immediate California organization, the Society of Jesus would be relieved of any future financial responsibility. {Nevertheless, a newly installed Jesuit provincial, Padre Juan de Palacios, was convinced that it was impolitic to defy "Virrey" (viceroy) Galve's stated opposition. Salvatierra overcame Palacios's resistance to the California project by spiritual blackmail; he suggested to the seriously ill provincial that his malady was the outcome of hindering a work dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto. When Palacios promised support for California, Padre Juan María took his novices to pray for the Virgin's intervention; the provincial recovered, and the score was settled. [61]}

At the end of 1696, there were other promising developments. José Sarmiento Valladares, the Count of Moctezuma and Tula, was made viceroy of New Spain. He proved more sympathetic to the California proposal than either of his immediate predecessors. Padre Provincial Palacios was induced to present Moctezuma with a petition that spelled out pertinent arguments for the Kino-Salvatierra plan: the Society of Jesus was prepared to reoccupy California at no cost to the king. There were, Palacios emphasized, "pious persons who would assist us with alms" and ships promised at no cost to the royal treasury; all this largesse could be lost by delay or through the death of willing benefactors. [62]

Salvatierra and Kino played on long-standing royal interests. Many of Spain's woes had roots in the relatively easily acquired riches of the New World. Gold and silver had paid for goods and wars and luxuries while trade and industry were neglected; but now that Spain was desperate, no one in power wished to close the door on possible California riches. While making no promises, Salvatierra reminded the crown of the advantages of thriving industries in pearl fishing and mining, both paying royal taxes, and a port in California to assist the profitable but troubled Manila galleon trade with Asia. In the fashion of the time, a few other arguments were advanced that may have weighed little in serious councils but could be cited publicly for pious effect. The Atondo expedition had come away with three California natives whose people had been promised their return; Spanish honor was at stake in making good that promise. Moreover, Eusebio Kino and the other Jesuits, Padres Juan Bautista Copan and Matias Goñi, had begun the religious instruction of many <17 > natives. Further neglect of these converts would encourage them to relapse into their former heathen state, a blow to the faith and to the king to whom they had promised allegiance. [63] At the same time, Virrey Moctezuma was made the object of a private campaign carried out by Salvatierra in his typically thorough and pragmatic Jesuit fashion: the persuasive missionary obtained an audience with the viceroy's wife, Doña Andrea de Guzman, and won her over as a most effective advocate. [64]

The proposal now had the ear of the viceroy and the Audiencia of Mexico. Stated simply, a responsible group of churchmen was proposing to give the crown a long-sought domain without expense to the royal treasury. Under these terms, there were no reasonable grounds for refusal. On 5 February 1697, Virrey Moctezuma granted Salvatierra and Kino a license to establish their mission in California. This license was exceedingly explicit about the powers and responsibilities that it conferred. On the paramount issue of funding, the viceroy wrote, "I concede the license which they request with the condition that nothing from the royal treasury can be drawn nor spent on this conquest without his Majesty's order." [65]

Salvatierra had been too shrewd to volunteer the services of his order or to undertake to pay all costs without receiving concessions in exchange. He boldly asked for and got control over matters normally administered by secular authority. His license broke with tradition and set precedents: Jesuits were given military powers. The superior of the mission to California was allowed to retain any armed men whose salaries he could pay. He had the power to choose and dismiss officers and, by inference, common soldiers; the viceroy merely had to be informed of changes. In the same manner, the missionary leader could appoint and remove civil authorities from office. [66] In exchange, the holders of the new license gave the easy promise that all conversions would be made in the name of the king, and the difficult promise to pay every peso of California costs.

The Pious Fund of The Californias

As soon as signs were favorable, even before the license was granted, a campaign was launched to obtain endowments. Salvatierra and Kino, patricians both, had networks of friends in high places to suggest who could be courted, how, and by whom. However, the problems of distance and slow communications remained. Kino, at work in the Pimería, was at the farthest extremity of New Spain; Salvatierra was in Guadalajara; most benefactors and royal officials were in or near Mexico City. Influence was exerted within the order and, in January 1696, Salvatierra was transferred to be rector and master of novices at the Jesuit college of Tepotzotlán, near the capital city. As soon as he was <18> granted the license to open California, he was released from other duties and freed to go in person to solicit donations. At about this time, Padre Juan de Ugarte enlisted proudly as a third beggar for California. This prominent Jesuit, then a professor of philosophy at the Colegio Máximo in Mexico City, threw himself into the fund raising with the same energy and dispatch that would characterize his later missionary endeavors. [67]

[Editor's Note: In January and February 1696 Kino joined with Salvatierra and Ugarte in Mexico City in the advocacy campaign and the further planning for the Jesuit return to California. Kino rode 1,200 miles in 53 days o Mexico City to save the Pimería Alta missions from their threatened closure and personally presented his "Biography of Father Saeta" to governmental and religious authorities. For more about Kino's Saeta Biography and protection of O'odham after the Tubutama Uprising, click Missionary.]

The upper classes in the Spanish colonial world had accepted the evangelical and charitable enterprises of the church as part of their responsibility. They applauded and esteemed people who gave generously to pious works. ….

But, at first, California did not appeal to the wealthy who engaged in fashionable philanthropy. Past failures had been well publicized. The skepticism of leaders in both church and government was well known. Many viewed Salvatierra and Ugarte as madmen because they proposed to do with private alms what immense sums from the royal treasury had failed to accomplish. [69] One affluent churchman showed his irritation by dismissing Juan de Ugarte by putting one peso in his doffed hat. The tide finally was turned by unexpected, gifts from two men reputed to be practical and tight fisted. Alonso Dávalos y Bracamonte, the Conde de Miravalle, and Mateo Fernández de la Santa Cruz, the Marqués de Buenavista, each gave one thousand pesos - with striking public effect. The accounting soon showed eight patrons, five thousand pesos in hand, and ten thousand more promised. [70] It was a good beginning, but Salvatierra knew that the endowment for a new mission area would cost several tens of thousands of pesos, and ten thousand pesos was the cost of an elegant home, a year's income for a very rich man, or the dowries for two of his daughters.

However, the California cause was alive; circles of interest widened and soon <19> included the first major contributor. In July 1696, Juan de Caballero y Ocio, a wealthy secular priest in Querétaro, donated twenty thousand pesos for the permanent support of two missions. [71] Another benefactor, Pedro Gil de la Sierpe, treasurer of His Majesty's royal exchequer at Acapulco, had wealth and a position from which he could make invaluable contributions. In October of the same year, he arranged to have the "Santa Elvira," an old ship belonging to the king, made fit for service and then offered it for Salvatierra's use. Don Pedro later donated a larger vessel, the "San Fermín," a large launch named "San Javier," and a small launch called "El Rosario." Both launches would serve long and well in California. The cost of the three vessels, plus Gil de la Sierpe's other contributions, represented more than twenty-five thousand pesos; in addition, he paid to maintain one soldier in California.

With such examples of pious generosity, more of the wealthy contributed. Skeptics were stilled as an endowment grew that might actually finance the quixotic venture. All money and property promised to Salvatierra, Kino, or Ugarte was pooled to form a single financial entity, a trust fund in support of California missions. A major new post was created - "padre procurador de Californias" - administrator of finances to oversee all monetary activity and record keeping for the new adventure. Salvatierra chose Juan de Ugarte, who had performed admirably in similar positions with Jesuit schools, to assume this vital responsibility. [73] Ugarte installed a central bookkeeping system and used the donated funds to buy "haciendas," rural properties that were profitably devoted to raising sheep or cattle. [74] These investments formed the basis of the Pious Fund for the Californias, an entity that eventually grew to a value of several million pesos and endured for over two centuries. [75]

Kino's California Return Denied Again

Just then an unforeseen obstacle blocked the path to California: a rebellion broke out at a mission in the remote Tarahumara. Sparks from the uprising ignited disorder all along the frontier of northwest New Spain. [81] Soldiers, ships, and supplies were diverted to fight the revolt; promises long-made to Salvatierra were set aside. A slighter spirit than his might have despaired; but the padre never doubted the divine inspiration of his mission; he had promised this conquest to Our Lady of Loreto and, in her name, responded to adversity with characteristic energy and fervor. While visiting the Tarahumara and doing what he could to calm the uprising, he continued to correspond regularly with actual and prospective supporters of his California plans. [82] ... <22>

When most of the supplies were in and repairs effected, the expedition waited for two vital elements: more soldiers and Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino. As time dragged on, it became apparent that presidios on the frontier feared additional uprisings and were unwilling to release men who had volunteered for California. [85] At the end of September, a letter from Kino shocked Salvatierra. The great pioneer of the Pimería Alta had received the permits from his provincial, Juan de Palacios, and from Virrey Moctezuma freeing him to go to California. He sent them to Padre Horacio Polisi, superior of the Sonoran missions, and took the trail to Guaymas to join Salvatierra. However, Padre Polisi immediately wrote to the provincial to protest that in those troubled times only Kino could control and placate the disturbed neophytes of the huge area he had evangelized. Moreover, Polisi informed the governor of Sonora and New Mexico, Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate, of Kino's release. The governor importuned the viceroy in the strongest terms, insisting that Padre Kino was worth more than a presidio in an area that threatened revolt. Both the provincial and the viceroy gave in to the arguments. Kino became the victim of his own success as he was ordered back to his mission. Padre Francisco María Piccolo was released from his mission in the Tarahumara to take Kino's place. For the second time, Spanish officialdom had denied Kino a return to California. [86] .... <23>

When Padre Juan María de Salvatierra landed at [Loreto] Conchó, he needed all his Tarahumara experience and all of Kino's information and advice to gain a foothold among California's people. [1] … <27

The Dependence of Jesuit California on Kino's Sonoran Missions

Before their campaign to open California began, Salvatierra and Kino foresaw that money alone might not be able to sustain their California venture. Both padres recognized that Mexico City and Guadalajara were far away and emergencies were inevitable. Their prospective settlement would need a nearby, reliable source of food. [99] Therefore, Padre Kino pioneered missions that had the potential to create surpluses of livestock, missions located in the Sonoran territories near the part of California that he hoped to evangelize. [100] Coincidentally, Kino's own mission field, the Pimería Alta, lay just north of the most <150> populous and prosperous of all the Jesuit missions, those along the broad, fertile banks of the Rio Yaqui.

Kino and Salvatierra were men of stature who had regular dealings with important figures in society, finance, politics, and the church. They met little opposition when they decided to use Sonoran missions as their springboard and larder. No other Sonoran Jesuits had wide influence; none would have been likely to oppose contributions to so popular a venture as that of brother Jesuits opening California. Thus, as soon as Salvatierra's cross was planted on the opposite shore, Sonoran missions began to feel the pressure of his needs. One of his ships returned for provisions immediately after depositing the first shore party, and at least five more crossings for supplies were made during the first year of the settlement. [101] In October 1700, Kino collected and shipped seven hundred cattle donated by Jesuit missionaries in the Pimería and Sonora. [102]

In 1701, Salvatierra joined Kino on one of his many explorations northwest in the Pimería Alta, this time to look for a usable land route to California. [103] That objective was not achieved, but on his return to Guaymas, Salvatierra seized the opportunity to establish San José, a "California" mission that could serve as a supply depot near the great harbor. [104] Meanwhile, Salvatierra and Kino continued their letter-writing campaign to people in high places. In response, Padre Provincial Francisco de Arteaga congratulated Kino on the discovery of potential mission sites in the northwest, "because those missions, once established, will become the support of California." [105] Padre Juan María informed Tirso González, the Jesuit general in Rome, that Arteaga had instructed his missionaries in Sinaloa and Sonora to provide assistance to California. Salvatierra asked González to thank the helpful provincial and the missionaries who had responded with contributions. [106] The padres' active correspondence reflected not only California's long-term dependence on outside help, but also the acute food shortages at Loreto in 1701 and 1702. Shipments from the Pimería and Yaqui missions enabled the colony to survive. [107]

Padre General González conferred several powers on Salvatierra to facilitate his leadership, one of which was the right to transfer any unneeded or undesired missionary from California to Sonora or Sinaloa. [108] In 1703, Salvatierra used that power to send Padre Gerónimo Minutili to Sonora. There, he was trained by Kino and placed at Tubutama, a mission that raised cattle and served as a way station between Kino's headquarters at Misión de los Dolores and San José, the new California mission at Guaymas. [109] A year later, Kino sent the Jesuit general a glowing description of progress in California - and reminded him of the importance of the Sonora-California relationship by enumerating the contributions he was able to make through San José de Guaymas. [110] From 1702 to 1704, food shipments from the Pimería Alta and Yaqui missions continued to be crucial to Loreto's survival. [111]

In 1704, Salvatierra sent Padre Piccolo, his right hand, to Guaymas to further develop Misión de San José and to thank the missionaries of the Yaqui and encourage their continued support. Piccolo received many cattle from <151> Kino, most of which he shipped to needy California. Piccolo also received the news that he had been appointed padre visitador of the Sonoran missions. [112]] Letters he wrote during his four years as visitador show that he kept close contact with Padres Kino and Minutili and channeled needed supplies to California. [113]

In 1706, Eusebio Kino still had his mind on what he called "the little sister across the gulf," [114] His plans were as ambitious as ever, encompassing nothing less than a ring of missions around the head of the gulf to serve and lead to the peninsular missions. [115] Padre Piccolo, then his superior, wrote to thank him for his continuing assistance to "the poor padres of California."[116] In 1709, while California suffered serious epidemics and food shortages, Kino rallied support. He heard from Salvatierra that, by disposition of the Jesuit general, Kino's principal obligation was to help California. [117] He had been the first driving force behind the Jesuits' return to California. During the twenty-six years after his own mission to the peninsula was suspended, he was probably the most vital benefactor of the new mission that took its place. Kino died in 1711 at age sixty-six. He has been recognized for his vision, but his efforts toward, and material contributions to, the development of the peninsular mission have been underappreciated in California annals. …<152>

"Antigua California: Mission and Colony on the Peninsular Frontier, 1697-1768"

Harry Crosby

To view and download excerpts, click

Kino: Founder and Builder of California document (pdf)

Kino: Founder and Builder of California document (text)

End Notes

For Antigua California Notes on Kino and the Jesuit return, click

Antigua California Kino Notes document (pdf)

Note references appear in brackets [number] in book excerpts above.

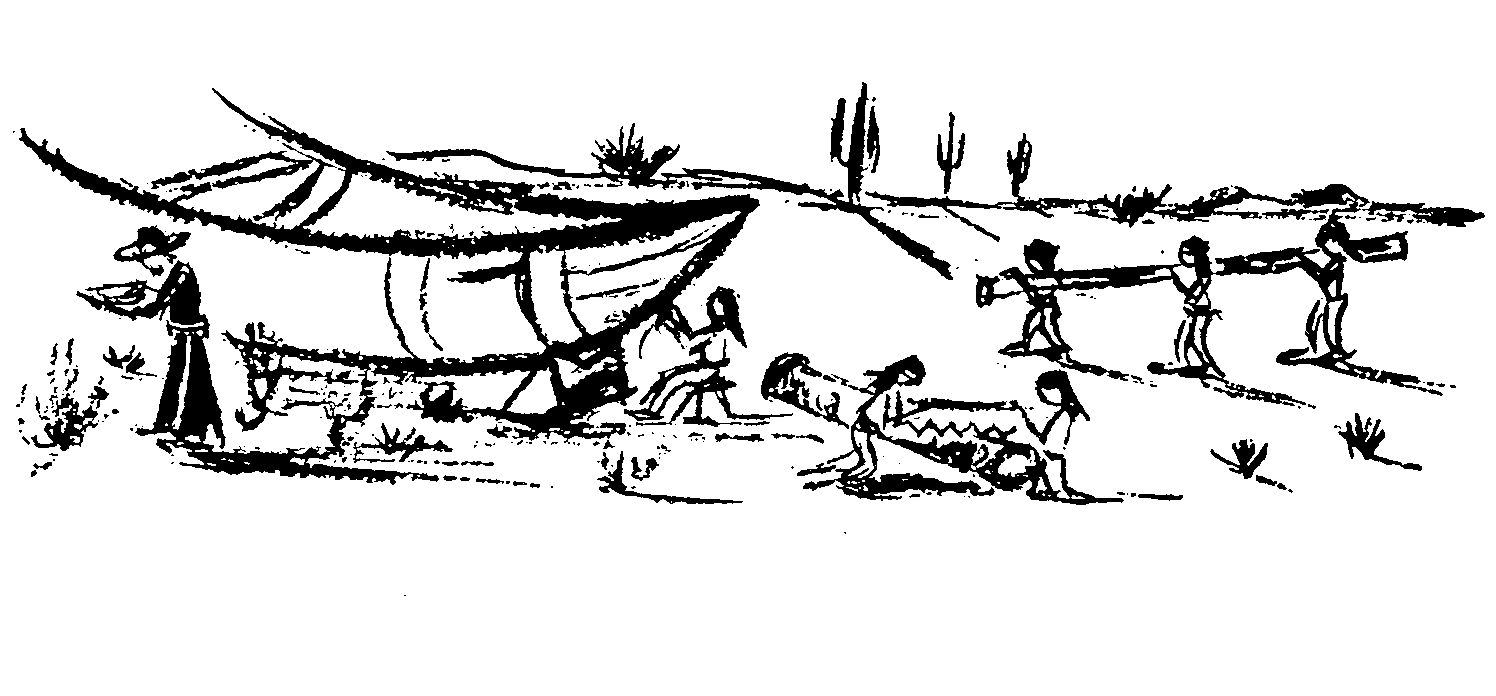

Kino Building Boat for Shipping Wheat and Cattle of HIs Sonoran Missions to Baja

Artist Ettore "Ted" DeGrazia

Kino's Baja Relief and Supply - Sortillón

For more information about the importance of Kino's California mission relief and supply efforts in the building of the Californias, click →

http://historiadehermosillo.com/htdocs/kino/KINO/KINO.HTM

Web author Manuel de Jesús Sortillón Valenzuela masterfully narrates Kino's efforts and vision for the Californias with with historical correspondence, maps and images. See chapters 10 through 16 as to selected events. Kino, as a pioneer builder of California, although not often recognized is key to understanding Kino's life and work on the Spanish frontier.

The Sortillón web site written in Spanish is entitled "Francisco Eusebio Kino - El Padre de Sonora." Kino was called by both his baptismal name of Eusebio and his vow name of Francisco. Kino added Francisco to his name after he prayed for the intercession of his patron saint Francis Xavier while near death at the age of 18. After recovering from his illness Kino vowed that he would become a missionary and Jesuit like his patron saint Franics Xavier, the great missionary to the people of Asia.

Kino and Salvatierra

Ernest J. Burrus

Tumacacori, Advocacy Campaign and Return to The Californias

1690 - 1697

Before the year 1690 was out, he [Juan María Salvatierra] could ride northward to visit Pimería Alta; and, in the name of the Provincial Ambrosio Odón and the General Noyelle, learn what means could best promote this new mission field attended to by Kino. The two great missionaries were to meet for the first time.

Salvatierra reached the main Pimería Alta mission of Dolores on Christmas Eve, and celebrated Mass in the "new |27| and spacious church" soon to be completed. Both missionaries then devoted a month to reconnoitering a vast territory, much of which not even Kino had yet visited.

The detailed story of their tour was recorded in Kino's journal and has been frequently retold. [38] Suffice it to say here that Salvatierra's visit was significant and successful for two main reasons: first, the travels of the two missionaries were the prelude to a life-long cooperation that led to the establishment and consolidation of the Lower California missions; secondly, Salvatierra was convinced of the peaceful condition of Pimería Alta and the sincere desire of the Pimas for more missionaries.

By Holy Saturday (April 14) of 1691, Salvatierra had left the northern missions for a short time and was back in the Mexican province proper; for on that day he sent off a letter which is still extant, and a few months later his boyhood friend Zappa wrote him from Mexico City. [39]

The next important milestone in the life of our missionary was his designation on January 8, 1693, as rector of the Jesuit College in Guadalajara. News of the recent appointments traveled fast: Zappa wrote him the next day from Mexico City to congratulate him. [40]

Salvatierra himself looked upon his new office as a serious |28| obstacle to his more important task of reactivating the California enterprise. He did not hesitate to let Jesuit authorities in Mexico City and Rome know his attitude. That Kino seconded his efforts is evident from the Jesuit General Tirso González' answers of May 21, 1695, and July 28, 1696, to the Mexican Provincial Diego de Almonacir [41]

After exactly three years as rector of the Jesuit College in Guadalajara, he was designated by the general, on January 8, 1696, rector and master of novices at Tepotzotlán, The new triennial appointments were published that day as Salvatierra rode into Mexico City from Guadalajara. That very same day, by a most extraordinary coincidence, Kino arrived in the same capital from far-away Pimería Alta to plead with ecclesiastical and civil authorities for the survival of his missions now threatened with extinction because of the uprising which culminated in the assassination of Father Francisco Javier Saeta. [42]

The threat to withdraw soldiers and missionaries from Pimería Alta, if put into effect, would have sounded the death knell to the ambitious plans of both missionaries, for not only would the Dolores group of missions have to be abandoned but all thought of establishing centers in Lower California would have to be sacrificed for the foreseeable future.

The two great missionaries co-ordinated their strategy and both won out. They both won to their side the new Provincial Juan de Palacios. Kino finished writing his biography |29| of Saeta, which was not so much a life of the young martyred missionary as an apology for the peaceful evangelization of the Pimas and a convincing defense of the innocence of the vast majority of them. [43] He also put the finishing touches to the two great maps he intended should illustrate the Saeta biography. [44] On February 8, 1696, after exactly a month's stay in Mexico City, Kino mounted his horse for the return trip to Dolores. [45]

Even as rector and master of novices in retired Tepotzotlán, Salvatierra turned to influential civil authorities and generous benefactors to promote the California enterprise. As Kino long before him, Salvatierra came to realize that he must remain independent of royal financial assistance. Accordingly, he started to beg alms for the settlement of the Peninsula. These sums were to constitute what was later known as the Pious Fund of the Californias. In a long series of letters to the Attorney General José Miranda Villaisán, the earliest of which is dated from Tepotzotlán, June 8, 1696, he urged the resumption of the peninsular missions. Before the year was out, he repeated his plans with greater insistence in his messages to the same recipient, on August 9, October 30, December 21, and possibly in other documents no longer extant. [46] |30|

At Salvatierra's persistent urging, the Provincial Juan de Palacios requested the viceroy's authorization for entrance into Lower California in order to establish missions there. [47] Conde de Moctezuma's main difficulty derived from a royal decree, dated from Buen Retiro, June 18, 1696, which forbade any payments being made from the royal treasury without the king's specific approval. [48]

Palacios and Salvatierra solved the viceroy's scruples on the point by calling to his attention that not a single peso was being requested for the enterprise; they were asking for authorization, not for funds. [49]

The viceroy's authorization is dated February 5, 1697. The document records the fact that the provincial presented a memorial on the enterprise to be undertaken and a letter of the Jesuit general approving Salvatierra and Kino for the evangelization of the natives of the Californias. [50] |31|

The Conde de Moctezuma then reviewed the efforts of the previous expedition, noting that 225,400 pesos had been spent on it. The royal decree of December 2, 1685, had suspended, not ended, the conquest of the Peninsula. The motive indicated by the decree was the priority to be accorded to the defense of Nueva Vizcaya; accordingly, the California enterprise was not to be considered as having been forbidden by the king. [51]

The viceroy went on to say that he was encouraged by the reports of Salvatierra and Kino telling of the mission successes without any royal financial help. [52] The present California enterprise was also to be undertaken solely with the support of freewill offerings. He feels in conscience bound to grant the authorization requested until the king is informed and gives a definitive decision. He repeats that nothing whatever is to be given by the royal treasury. [53]

He authorizes the Jesuit missionaries to take with them the armed men and soldiers whose salaries they can pay. The officers are to be chosen by the Jesuits, and they may be dismissed by them if not satisfactory, but the viceroy is to be informed about new appointments. The soldiers have the same status with the same duties, powers, and privileges as those of the royal army in the other presidios of New Spain. All conquests are to be made in the name of the king. The missionaries may also name civil authorities; but, again, they are to inform the viceroy. He concludes the historic document by expressing his confidence that the enterprise will meet with royal approval. [54] |32|

The next day the viceroy added other pertinent documents to his official authorization. Overjoyed at this favorable turn, Salvatierra did not tarry in Mexico City, but set out on the morrow, February 7, 1697, for the Peninsula. [55 ] He traveled via his old missions, intending to meet Kino en route in order to continue with him to Lower California. Because of new disturbances in Pimería Alta and the threat of a more general uprising, civil and military officials begged Kino to remain with them. He acceded to their pleas. [56] Salvatierra continued without him, hoping that he would join him as soon as conditions on the northern frontier permitted.

On October 10, 1697, Salvatierra boarded a small ship in the west-coast harbor of Yaqui, but could not get under way until a day later. After going ashore on the 15th and trying several sites then and later, they finally sailed into San Dionisio Bay and landed, on the 19th, at a spot known to the natives as "Conchó" and renamed "Loreto" by Salvatierra. The missionary's trip and historic "conquest" of Lower California are related in great detail in his letter of November 27, 1697, to Father Juan de Ugarte, treasurer in Mexico City for the enterprise. In the text of the present volume this report is translated in its entirety. [57]

III. From Loreto to the Head of the Gulf and Return

October 19, 1697, to May 2, 1701

Before the brave "Conquistadores" could unpack their supplies and set up even provisional dwellings, a downpour |33| drenched them during the night of October 23, 1697. [58] If the abundant rain augured well for the future of crops and grazing lands, it was very inconvenient at the moment for establishing their diminutive fort and town. ...

Finally, on Wednesday, November 13, after seeing that no reinforcements were arriving, |34| four groups of natives began their attack on the Spanish compound from as many directions. ... After several natives fell wounded mortally, the rest retreated to a safe distance and then sent their women and children to sue for peace. ...

By the beginning of June, 1698, the little colony in California was almost starved out. The launch had crossed forty days previously to Yaqui for provisions, but a stormy Gulf kept it from returning to Loreto. No word had been received in answer to the missionary's letter of November, 1697, sent to Guadalajara and Mexico City. The "Conquistadores" of Lower California were reduced to eating the bran they had brought along for the animals.

Finally, on June 19, 1698, one of the ships from Nueva Galicia, the "San José", was sighted, and two days later its supplies were unloaded. Seven more Spanish volunteers came to serve in California; the little colony now had twenty-two Spaniards.

Salvatierra's letter of April I, 1699, to Ugarte was packed |36| with news dealing with events in the Peninsula and the main land from October of 1698 to April of 1699, the most dramatic of which was the account of the trip of several California natives to the Jesuit missions on the mainland, their cordial reception, and the enthusiastic report they made on their return to Lower California. [64]

Salvatierra also proudly reports the first boat repairs effected in California: the keel of the "San José" was successfully replaced. A considerable portion of this long report was devoted to the expeditions carried out by both Salvatierra and Píccolo. Another "California first" was the introduction of mail service between Loreto and various settlements in order to keep the missionaries and the soldiers informed. ...

Salvatierra, despite all his work at Loreto, took time out to explore the area about San Juan de Londó, in the San Bruno-San Isidro area where the Atondo-Kino expedition had made its headquarters, and which under Salvatierra became another mission.

These letters are among the most optimistic ever penned by Salvatierra. ... Prospects for the future are bright, but financial help is urgently needed at this decisive moment of the enterprise. ...

The lengthiest extant letter written by Salvatierra is addressed to Father Francisco de Arteaga, provincial of the Mexican Jesuits. It was penned after Salvatierra's epoch-making expedition with Kino through Sonora to the immediate vicinity of the head of the Gulf of California in order to discover a land passage to the Peninsula from the Mexican mainland. [71] He returned to his home mission on May 21, 1701, and finished writing the report on or after August 29, 1701. [72]

The account covers the activities of Salvatierra from after his last report of November, 1699, to the day of his return to Loreto, May 21, 1701. Elsewhere I have written at great length on Salvatierra's participation in this expedition, which is the most important event recorded in his letter to Arteaga. [73] Here only a few of the highlights need to be referred to, especially since Salvatierra's own summary of the report is reproduced in a complete English translation in the present volume. [74] |40|

Hard pressed for supplies, and with the "San Fermín" out of service and the other ships still on the high seas, Salvatierra was forced to use the one remaining boat, the "San Javier", in order to secure provisions from the mainland for his starving colony. He took with him five Californians so that they could see the advantages of the more civilized way of life of the mainland mission natives. Invited by a Tarahumaran embassy, Salvatierra and his charges visited his old missions. He was back in Loreto on June 21, 1700.

Shortly afterwards, the "San José" came with more abundant supplies sent from Mexico City, Guadalajara, Acapulco, and other cities. It also brought the sad news of the death of the great benefactor of California, Don Pedro Gil de la Sierpe.

The "San José" likewise brought letters from Provincial Arteaga, ordering Salvatierra to explore the possibilities of a land route from the mainland to the Peninsula. Shipments across the Gulf had proven exorbitantly expensive, slow, and uncertain, often bringing the colony to the verge of starvation.

Accordingly, Salvatierra re-crossed the Gulf in January of 1701. Rain and sleet along the western coast of Sinaloa forced him to seek warmer weather in the interior. He first went to Matape. At this important Jesuit center, the missionaries urged him to make a joint expedition with Kino in order to ascertain the nature of Lower California. Father Kappus showed him some blue shells given to him by Kino; and, from their presence on the mainland, argued to the continuity of Sonora with Lower California.

Salvatierra set out for Dolores, Kino's home mission, and, on learning that Kino was in Caborca, continued on to the |41| latter town. The two great missionary explorers and builders crossed the Sonoran desert via Quitobac to beyond Santa Clara (Pinacate) and Tres Ojitos, immortalized on Kino's 1701 map. [75] They pressed forward towards the head of the Gulf. Both were convinced that they now saw that the land continued from the mainland to the Peninsula.

Before crossing the Gulf to Loreto, Salvatierra established Guaymas, north of Yaqui, as a California supply base. [76]

IV. Missionary and Administrator in Baja California

May 21, 1701, to October 21, 1704

With the numerous difficulties arising in Spain due to the weakness of Charles II, the change of dynasty, and the protracted War of Succession, little thought was given to such a marginal enterprise as that of Lower California. By the beginning of July, 1701, however, the Consejo Real, Spain's Ministry of Colonies, began to study the numerous reports sent in by Salvatierra, Ugarte, and the Mexican viceroys. On July 17, 1701, it ordered an annual subsidy of 6,000 pesos to be accorded to the California enterprise, and at the same time requested a complete up-to-date report. [77]

This favorable decision came at a crucial moment. By the |42| summer of 1701, the situation in Loreto had become desperate. Salvatierra called a council and reluctantly but firmly urged the abandonment of the enterprise. Father Juan de Ugarte, who, in the meantime, had turned over his office as treasurer of the California missions to Father Alejandro Romano, and had joined the peninsular missionaries, argued against forsaking the missions established with such great sacrifice. [78] ...

Salvatierra's letter, dated September 15, 1702, to the Fiscal Miranda is one of profound despair. [84] The delay of the "San Javier" brought the Loreto colony to the verge of extinction for lack of provisions. At long last the launch sailed into San Dionisio Bay; it was July 22, 1702, at the very time Píccolo was striving so bravely to get the Mexican officials to comply with the royal decree. ...

By the time Salvatierra penned the letter, it had become evident to him that the annual subsidy of 6,000 pesos granted by the royal decree was insufficient. [87] Accordingly, the missionary dispatched Father Basaldúa with the boat "El Rosario" to attend to its thorough overhauling and to try to secure the promised subsidy. After many months, Basaldúa returned with another capable missionary, Father Pedro de Ugarte, brother of Juan, but with no part of the royal grant.

In this desperate situation, Salvatierra turned again to the one source of assistance which had never failed him - the northern Jesuit missions. [88] Píccolo crossed over that same year to Guaymas, the port established by Salvatierra in 1701, [89] and then continued through the missions as beggar extraordinary in behalf of Baja California. Needed help began flowing through Guaymas for the starving peninsular missions. Píccolo then stayed on as visitor of the Sonoran |45| missions from 1705 to 1709, [90] at the very time when his presence was most needed in California because of the appointment of Salvatierra as provincial superior of all the Mexican Jesuits.

V. An Interlude: Salvatierra is Provincial

October 21, 1704, to September 17, 1706

..

The viceroy decided to call a meeting in which he wanted Salvatierra to participate. [93]

Salvatierra set out from Loreto on an unrecorded autumn day in 1704 for Mexico City. Inasmuch as he arrived in the capital at the beginning of November, 1704, he must have started on his trip in September. As we have seen, the Visitor Piñeiro died on October 21, 1704, while Salvatierra was en route to Mexico City. The Jesuit general had appointed Salvatierra as Piñeiro's successor, and hence his term of office began on October 21, 1704.

The foremost concern of Salvatierra was the evangelization and settlement of the Peninsula. Fearing that his term of office as provincial would interfere with this more important apostolate, he made every effort to avoid serving as superior of the Mexican province. His reasons for refusal, however, |47| were not accepted; and he had to take over the government of the entire province.

The War of Succession had depleted the royal coffers in Madrid and Mexico City. As a result, not only did California not receive its allotted subsidies; but all the Mexican Jesuit missions-Sonora, Sinaloa, Tepehuanes, Tarahumares, and Las Sierras - failed to obtain the promised annual contributions. More than a hundred missionaries, who, on paper, received 300 pesos annually, had not been paid for four years; the royal debt to them came to some 120,000 pesos. [94] Nor were the other Jesuit communities in Mexico able to come to the aid of the missionaries, since they themselves were hopelessly in debt. The Mexican Province had to borrow heavily in order to keep the missions going. Its official records show that on April I, 1706, its debts totaled 512,443 pesos; individual houses were even worse off proportionately; thus, the main college in Mexico City owed 222,164 pesos. [95] Obviously, both the Mexican Province and its houses had reached the very limit of their credit.

In the light of this situation, we can better appreciate two basic facts: the generosity of the northern missionaries during all these years in helping Lower California, and Salvatierra's efforts to secure financial assistance for all the missions.

The viceroy had summoned a meeting for June 27, 1705, in order to discuss the financial plight of the Mexican Jesuit missions, those of California included. From his point of view, there was nothing to discuss: all of Mexico's |48| wealth must be sent to Spain, the Mexican Jesuits were wealthy and needed no assistance, especially not those of California who had so many pearls. [96] ...

Despite the failure of the northern Jesuit missionaries to receive more than one annual subsidy in all those years, they continued to the best of their ability and means to help the even less fortunate peninsular missions. Foremost among all was Kino. Cows, horses, mules, sheep, goats, corn, flour, and all else that he could spare were sent by the Dolores missionary to Guaymas to be shipped across the stormy Gulf. The Salvatierra-Kino correspondence is most abundant for this period, and its central theme is the provisioning of Lower California.

But, for Salvatierra, it was not sufficient to secure aid for |49| the peninsular missions; he wanted to see his beloved California again. In August of 1705, after visiting officially, as provincial, the Jesuit College in Guadalajara, he took with him Brother Jaime Bravo [98] and continued to Matanchel, where they embarked for Loreto. From there, he wrote to Kino and to the other missionaries to persevere in their generous assistance to California.

Salvatierra remained on the Peninsula through September and October of 1705 ... |50|

At the end of October, 1705, Salvatierra embarked at Loreto for Matanchel, from where he returned overland to Mexico City. He now took the most important step of his life, one that saved the California enterprise and put it on a sound financial basis. Inasmuch as promises from individual benefactors as well as royal decrees ordering annual subsidies had proven insufficient and unreliable, [100] he arranged for the income-bearing property of the missions to be kept safely invested in farms and herds of cattle, the care and increase which ... is in charge of the person who is appointed by the Father Provincial to the office of procurator of California." Thus, the Pious Fund of California was to be are liable source of income for the peninsular missions until it was unscrupulously plundered by José de Galvez after the expulsion of the Jesuits from Lower California in 1768. [101] .. .|51|

"Selected letters about Lower California: Juan María Salvatierra"

Introduction

Ernest J. Burrus

Baja California Travels Series; No. 25

Excerpt: Jesuit Return to Baja California

For complete excerpt of Jesuit Return to Baja California with footnotes. click

Jesuit Return To Baja California document (pdf)

Jesuit Return To Baja California document (text)

The Pious Fund Of The Californias

Ernest J. Burrus

A private, rather than governmental, arrangement for financing the missions, first those of the Jesuits in Lower California (1697-1767), and then those of the Dominicans in the same Peninsula and of the Franciscans in Upper California. |68|

At the time when the Spanish financial resources no longer sufficed for maintaining an over-extended bureaucracy, fighting too many and too costly wars, and also supporting an ever more burdensome program of evangelization, the latter was bound to suffer. When the Atondo efforts at settling Lower California (1683-1685) failed, and Spain suspended indefinitely further attempts, Kino turned in 1687 to private enterprise (farming and ranching) and the assistance of benefactors to sustain his mainland centers, which he planned would also provide for the less productive peninsular missions. His system of financing the mission enterprise served as the pattern for the Pious Fund. The Jesuits became all the more convinced of the need for private subsidies when the insistent appeals (about 1686) of the influential Duchess of Aveiro in behalf of the Lower California enterprise failed. |69|

When finally Juan María Salvatierra obtained authorization from the Mexican Viceroy on February 5, 1697 to establish missions in Lower California, it was with the express proviso that no funds would be expended from the royal treasury. |70| This procedure was in striking contrast to the way all previous Jesuit missions had been established. Hitherto each missionary had received an annual stipend of 300 to 350 pesos and 35 for a school. |71| In the peninsular enterprise, the Jesuits not only had to renounce all claim to such a subsidy, but they also had to agree to maintain the necessary military garrisons. To establish and support their missions and the necessary security, they turned beggars extraordinary: Salvatierra himself; Kino, who had been encouraging [56] him to undertake the enterprise; Píccolo, who was the first missionary to join him; Juan de Ugarte, who printed the letters arriving from the Peninsula and used them to inspire generous benefactors. |72|

After more than a century and a half of fruitless efforts of Spain to settle Lower California, Salvatierra succeeded in 1697 in establishing Loreto, a mission, a town (with a school) and a presidio. By 1701 the Pious Fund began to take definite form. The King, on learning of the importance of conquering, evangelizing, fortifying and settling the Peninsula, offered to assist financially. |73| As this was insufficient, private benefactors were appealed to. By 1720 the sum of 548,040 pesos had been given to the Fund. What was not spent on current needs was invested in landed properties.

The Jesuits had been in the Peninsula for less than seventy years when the decree of expulsion (June 25, 1767) was promulgated. They were never again to receive anything from the Fund they established.

The Fund was plundered by José de Gálvez, the visitor sent by the King to implement the decree of banishment. In order to pacify the northwestern tribes, he gathered large military forces and conducted various campaigns. These he financed with the money he appropriated from the Pious Fund. |74| The Franciscans from 1768 and the Dominicans from 1770 were supported by what was left of the Fund. The Spanish government had now to assign salaries to all the California missionaries.

Although Mexico won its independence in September of 1821, it was not until December 28, 1836 that Spain recognized it. No reference was made to the Pious Fund.

In 1834 the Mexican Congress had decreed the secularization of the missions of both Californias, turning them over to the secular clergy. Until Upper California would become American territory, the Mexican government entrusted Fray Francisco García Diego y Moreno with the administration of the Fund. The diocese, [57] with its seat at Monterrey, included both Californias.

In order to understand Mexico's position in regard to refusing to pay any sums for the Upper California missions after that region became part of the United States, it must be remembered that in the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty of February 2, 1848, it was stipulated (Articles XIII-XIV) that the United States government would make good to its citizens any claims against the Mexican government. The Jesuit Mexican Historian Maríano Cuevas rejected American claims for two additional reasons: the Fund belonged to the Jesuits and it had been established to support the missions in Lower not Upper California. |75|

On June 30, 1850, Monterey (the new spelling) limited its jurisdiction to Upper California, and on July 20,1853 it divided its jurisdiction with San Francisco.

The American government now supported the California bishops' claims on the Fund against the Mexican government. A mixed claims commission was drawn up by both governments on July 4, 1868. On its failure to reach an agreement, Sir Edward Thornton, British plenipotentiary in Washington, was chosen to arbitrate. His decision favored the California bishops, but had no effect on the Mexican government.

When the permanent tribunal of arbitration was set up at The Hague, the first case brought before it was the claims of the California bishops, supported by the American government (May 22, 1902). Again, the decision, given on October 14, 1902, was favorable to the Americans. The Hague ruled that Mexico should pay both the delinquent interest on the Fund and a perpetual annuity, in the future, Of $43,050.99. Mexico honored the debt until 1913, when it defaulted and nothing more was paid until 1967.

The whole problem came up again when the United States government, through President Kennedy, offered to return the disputed El Chamizal territory, formed by the Río Grande, at El Paso, Texas. After several years of investigation and discussions linking the Pious Fund and El Chamizal, President Díaz Ordaz [58] was able to inform the Mexican Congress on September 1, 1967: "The payment of $716,546 brings to a close the long-standing claim of the government of the United States of North America against ours in the case of the Pious Fund of the Californias. Thus, we are freed from the perpetual annuity to which the permanent court of arbitration at The Hague had condemned us in 1902." |76| [59]

A Unique Financial Arrangement: The Pious Fund Of The Californias

Ernest J. Burrus

Introduction

Jesuit Relations, Baja California, 1716-1762

Baja California Travels Series, Volume 47, 1984

Documents On Kino's Advocacy Campaign for Return to The Californias

Including Letters of the Jesuit Father General, Viceroy of New Spain, Salvatierra and Kino and Decree by The King of Spain

Kino Continues To Advocate For California Return

On His Journey to Work In Sonora 1686

The missionaries [from California] were appointed by their superiors to other Missions. Father Kino went to Sonora, the theater of his fervid zeal, whence he hoped to go to California. With this thought he left Mexico [City] on October 20, 1686, and on passing through the provinces of Tepehuana and Sinaloa he inflamed the spirits of the Jesuit missionaries there in favor of the conversion of the poor and forsaken Californians. One of the many who felt inspired for such an enterprise by the ardent words of Father Kino was Father Juan María de Salvatierra ...

Francesco Javier Clavigero, S.J.

Historia de la Antigua o Baja California , 1789

English translation from

Chapter 8: The Zeal Of Some Jesuits For The Conversion Of California And Its SuccessThe History of Lower California, 1937

Jesuit Father General Letter 1695

En cambio, el padre Tirso González, ignorante aún de la penosa situación, escribió a Diego de Almonacir una carta reafirmando su total confianza en Eusebio Francisco, dándole todo su apoyo para retomar la conquista y evangelización de las Califomias y enviándole un compañero. Así escribió el antiguo y fiel "amigo de Sevilla", ahora general de la Compañía de Jesús:

"Puedo decir que "me lleno de gozo" [75] al ver los muchos sujetos que esa provincia tiene empleados en sus gloriosísimas y dilatadas misiones de gentiles [donde] trabajan como verdaderos hijos de San Ignacio mirando sólo la mayor Gloria Divina y bien de aquellas pobres almas. [ ... ] Una relación he recibido del padre Eusebio Francisco Kino que me ha consolado mucho no sólo por lo adelantado que está en aquellos pimas la cristiandad, sino por la disposición tan buena que ha hallado en la entrada que hizo a finales de 1692, en que se reconoció |311| en tantas gentes los deseos de abrazar nuestra Santa Fe. Con ocho fervorosos padres que Vuestra Reverencia envió de nuevo a aquellas partes, se habrá adelantado mucho así en la buena educación de los que ya tenia el padre Kino reducidos, como a la conversión de los otros.

La facilidad que se ofrece, y veo en las cartas de los padres Kino y Salvatierra, del tránsito a las Califomias me obliga a instar de nuevo el que se procure la entrada de todas veras y calor; pues la navegación por la parte de los pimas es brevísima y la fertilidad de los parajes en que el padre Kino se haya es muy grande y en el caso que las Califomias no sean tan abundantes, puede darles mucho socorro, dándose las manos y ayudándose unas o otras. Y así encargo a Vuestra Reverencia con todo aprieto que en las diligencias que en México fueren necesarias y habrán escrito los padres Kino y Salvatierra, se ponga todo el cuidado posible para que se consiga lo que fuere necesario para aquella empresa. [ ...]

Considero que a los que hubieren de entrar les será de grande alivio el llevar consigo al hermano. Y sé que el hermano Juan Steinefer irá con gusto. Vuestra Reverencia le envíe luego a los pimas para que allí le ayude al padre Francisco Kino. Y esto Vuestra Reverencia lo ejecute, ahora se disponga la entrada alas Califomias, ahora no. Pues estoy seguro que es un muy buen operario catequizando e instruyendo.

Roma

21 de mayo de 1695

De Vuestra Reverencia siervo en Cristo

Tirso González. " [76]

Esto es apoyar incondicionalmente a un amigo y tener visión, como superior jesuita, para valorar e impulsar sus proyectos misioneros. Aquí dejamos, por el momento, a Eusebio Francisco Kino, muy reconocido y apoyado en Roma por el padre general, pero - como veremos en el próximo volumen - a merced de la sospecha, la hostilidad y el deseo de humillarlo que abrigaban sus superiores inmediatos de Sonora y México. |312|

Gabriel Gómez Padilla

"El Pésame"

en "9,000 Kilómetros a caballo: Pimeros años de Kino de Sonora" 2009

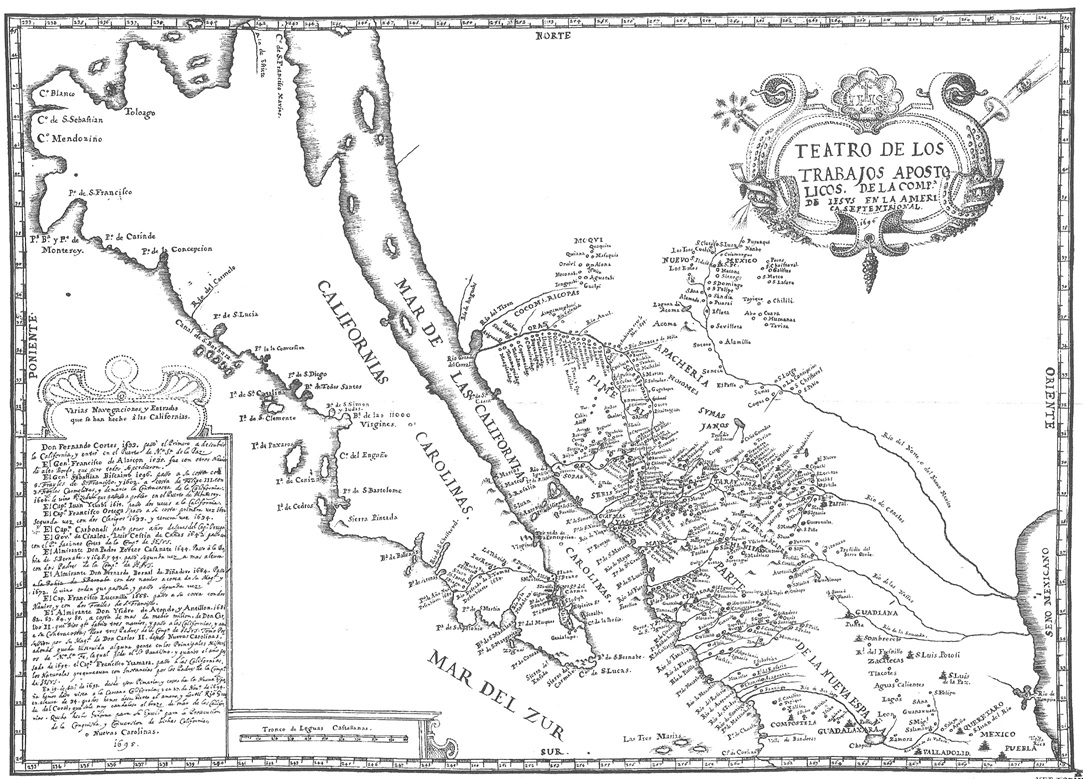

"Teatros de los Trabajos Apostólicos de la Compana de Jesús

en la America Septentrional"

Kino's Hand Drawn Map Illustrating His Padre Saeta Biography 1696

For the map in high-density pixel screens (size 8 mb), click

https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/623456

Kino's Use of History In Teatro Map of Previous Attempts To Settle California

To Advocate for Return

"Teatros de los Trabajos Apostólicos de la Compana de Jesús en la America Septentrional 1695

Various sea expeditions and entrances

made into the Californias. |39|

Don Fernando Cortéz set out in 1533 as the first to discover California, landing at the port of Nuestra Señora de la Paz. General Francisco de Alarcón went in other high-decked ships; all of which, however, were lost. |40|

General Sebastián Biscaíno went there in 1596, at his own expense with five Friars of Saint

Francis; and in 1602, at the expense of Philip III, with three Carmelite Friars he explored the west coast of California. In 1606 he received a royal decree ordering him to found a settlement in the port of Monterey. In 1615 Captain Juan Iturbi made two expeditions to California.

Captain Francisco Ortega crossed over to California the first time in 1632; this he did at his own expense. The second time (in 1633) he took two clerics with him. His third expedition was in 1634. |41|

Captain Carboneli undertook his expedition a few years after Captain Ortega. The Governor of Sinaloa, Luis Cestín de Canas crossed over in 1642, taking with him Father Jacinto Cortés of the Society of Jesus.

Admiral Don Pedro Porter Casanate disembarked in 1644 in the bay of San Bernabé; and in 1648 and 1649, taking with him two Fathers of the Society of Jesus, he made a landing further north. In 1664 Admiral Don Bernardo Bernal de Piñadero made an expedition in two ships at the expense of his Majesty, and in 1672 he received orders to make a second expedition, which he did.

In 1668 Captain Francisco Lucenilla made an expedition in two ships at his own expense, taking with him two Friars of Saint Francis. |42|

Admiral Don Isidro de Atondo y Antillón in 1681, 1682, 1683, 1684 and 1685, at the cost of more than a half million pesos furnished by Don Carlos II (whom God protect), built three ships, and crossed over to the Californias and even to the opposite shore. |43|

He took with him three Fathers of the Society of Jesus. He took possession of these New Carolinas for Don Carlos II. Some of the inhabitants were instructed in the principal doctrines of the faith and are pleading for holy baptism; last year (1694), when Captain Francisco Itamarra (Yramara) went to the Californias, the natives asked most insistently for the Fathers of the Society of Jesus. On December 19, 1693, we beheld from this land of the Pimas and coast of New Spain the nearby region of California: and again on November 27, 1694, at the thirty-fourth parallel, we discovered the pleasant and productive Río Grande del Coral which pours its vast volume of water into the arm of the Sea of California. I have compiled a report for his Excellency in order to reactivate the conquest and conversion of the said Californias or Carolinas. 1695."

History of California Exploration by Eusebio Franciso Kino.

Teatro Map Text in lower left box

Translated by Ernest J. Burrus in "Kino and the Cartography of Northwest New Spain"

Editor Note:Title and text about the history of the Spanish attempts to settle the Californias in Kino's handwriting together with his cartography. This map accompanied the "Biography of Padre Saeta" and was personally presented to the highest officials in Mexico City by Kino after he rode 1,500 miles in 53 days. Kino began his ride for peace and justice on November 16, 1695 from his Mission Dolores headquarters in order to protect the O'odham people from reprisals and to advocate for a renewed Jesuit effort in the Californias.

Kino updated many years later the history of the exploration and settlement of the Californias in his "Favores Celestiales" in Book VIII Chapter IV he entitled "Various Voyages And Expeditions Which Have Been Made To California Since The Beginning Of The Conquest Of New Spain"

Viceroy of New Spain 1697 Letter

Mexico City,

February 5, 1697

My attention has been called to the memorial presented by Reverend Father Provincial of the Sacred Order of the Society of Jesus, and the letter of most Reverend Father General Tirso Gonzalez, in which the latter approves (with the recommendations and high praise expressed in it) the persons of Fathers Juan Maria de Salvatierra and Eusebio Francisco Kino for the conversion of the natives of California.

According to the records of the Supreme Tribunal of Accounting and the royal officials, 225,400 pesos were paid out from the royal treasury for the building and fitting out of three ships, for the salaries and wages of the sailors and soldiers, and other expenditures incurred in previous attempts at winning over the natives of the realm of California, without being able to effect its conquest.

The records also show that the last effort was ordered suspended then, in virtue of the royal decree issued by the viceroy on December 22, 1685, because it was considered more imperative to defend the province of Nueva Vizcaya, endangered by a general uprising of the Tarahumara Indians. And, after spending considerable sums from the royal coffers on sending timely aid to the troubled area, it would not have been advisable to incur additional expenses in the conquest of California.

There would have had to exist a strong motive to disregard the decree of suspension and incur new expenditures. It would have been necessary to prove that the royal prohibition against the conquest and conversion of California was not absolute but was merely a temporary suspension occasioned by the circumstances of the time.

Keeping in mind the contents of the royal decree and also having before me the documents and reports by which the two Fathers, in their fervent zeal and diligence, show that by themselves (and with no other assistance) they have won over and baptized more than five thousand natives; aware that these people are persevering in our holy faith as they live in settlements and mining centers with the ardent desire that these Religious return to them for the administration of the holy sacraments and the imparting of religious instruction and exercises of piety and that the Religious would also win over other natives;" keeping in mind that the conquest and conversion of California is to be effected by the donations which the pious devotion of various individuals has offered to contribute for this holy and noble purpose; and realizing, finally, that the aim of His Majesty has been the continuation of this enterprise and that it would be a motive of deep remorse to abandon so many natives pleading for baptism in that mission field - for all these reasons, I have considered it my duty, as a Christian subject and servant of His Majesty, to grant, as I do now grant (and in the meantime, in view of this decision, to await what His Majesty wishes to determine) to these two Religious (in virtue of this decree) the appropriate authorization they request, with the proviso that, without subsequent orders of His Majesty, nothing can be issued or spent on the conquest from the royal treasury. This is an express condition for the use of this authorization and permission.

And, since it is but just to attend to the safety of these two missionaries and of their companions and to prevent the disastrous consequences of native or other uprisings in those distant-regions, or any other adversities, I authorize them to take with them the armed men and soldiers they can pay and provide with weapons at their expense; also an experienced Christian commander who meets with their complete approval and chosen by the Jesuits, who may remove him should he ever fail in his duty. They are to inform me whom they choose. And, if they remove him, I am to issue such orders as I consider appropriate for the service of His Majesty.

I grant to the commander and to the soldiers under him (so that they will gladly obey him in a service so pleasing to both Majesties) authorization to enter the land in order to effect the conquest and conversion of the natives. I also grant them all the privileges, honors and exemptions enjoyed by other superior commanders and soldiers of royal presidios and armies. The service in California will be reckoned as though it were given in time of actual war, in keeping with what His Majesty has declared in regard to service in the Parral presidio and in other forts of the realm and territories.

And until the royal decision has been made known, I grant them permission and authorization to hoist the flag and to enlist recruits to the extent necessary for the enterprise, with the understanding that all conquests are to be made in the name of His Majesty. And in order that the participants who go now or join the expedition later on live in peace and harmony, observing due courtesy and deference towards the Religious, I authorize them to appoint, in the name of His Majesty, ministers of justice whose orders are to be obeyed under the penalty inflicted on the disobedient. They are to inform me fully of the results of the expeditionand its progress.

I expect of the Jesuits, in their Christ-like zeal, to accomplish much in the service of God and to the satisfaction of the king, our lord, who will undoubtedly thank them, and that I shall be able to repeat that expression of gratitude in his royal name. Accordingly, the dispatches will be drawn up and the testimony will be recorded in order to inform His Majesty.

Conde De Moctezuma

Notes on The Viceroy's Support

Salvatierra and Kino won over Viceroy Moctezuma's wife, La Duquesa y Condesa de Sesa, and she, in turn, persuaded her husband to authorize the Jesuit entry into California. The conditions and provisos would have discouraged any less brave adventurers: not a penny of royal funds for the expedition, soldiers, sailors, missionaries then or in the future unless expressly authorized by the king. It was an arrangement unique in Spanish missionary annals. The Jesuits had not only to evangelize the natives unassisted financially but also become beggars extraordinary in order to support the enterprise.

Moctezuma's authorization for Salvatierra and Kino to undertake the conquest and settlement of the peninsula is not only the most important document of the Jesuit apostolate, but even of the entire enterprise. ... It defined the authority, privileges and obligations of the missionaries, military and townspeople. The authorization was the cornerstone of the most unique undertaking in the Spanish American dominions.

Salvatierra set out from Mexico City on February 5, 1697. According to the viceroy's authorization, Kino was to join Salvatierra en route and the two would go ashore together. But as civil and military authorities pleaded with Kino to remain in Pimería Alta in order to pacify restless natives, Francisco María Piccolo working at the time in Carichic, Tarahumara - took his place.

Salvatierra, accompanied by a few soldiers and servants, went ashore at Concho on October 19, 1697. As he carried an image of Our Lady of Loreto, he called the mission, town and fort by that name.

Success at Last: The Jesuit Apostolate

Ernest J. Burrus

Introduction

Jesuit Relations, Baja California, 1716-1762

Baja California Travels Series, Volume 47, 1984

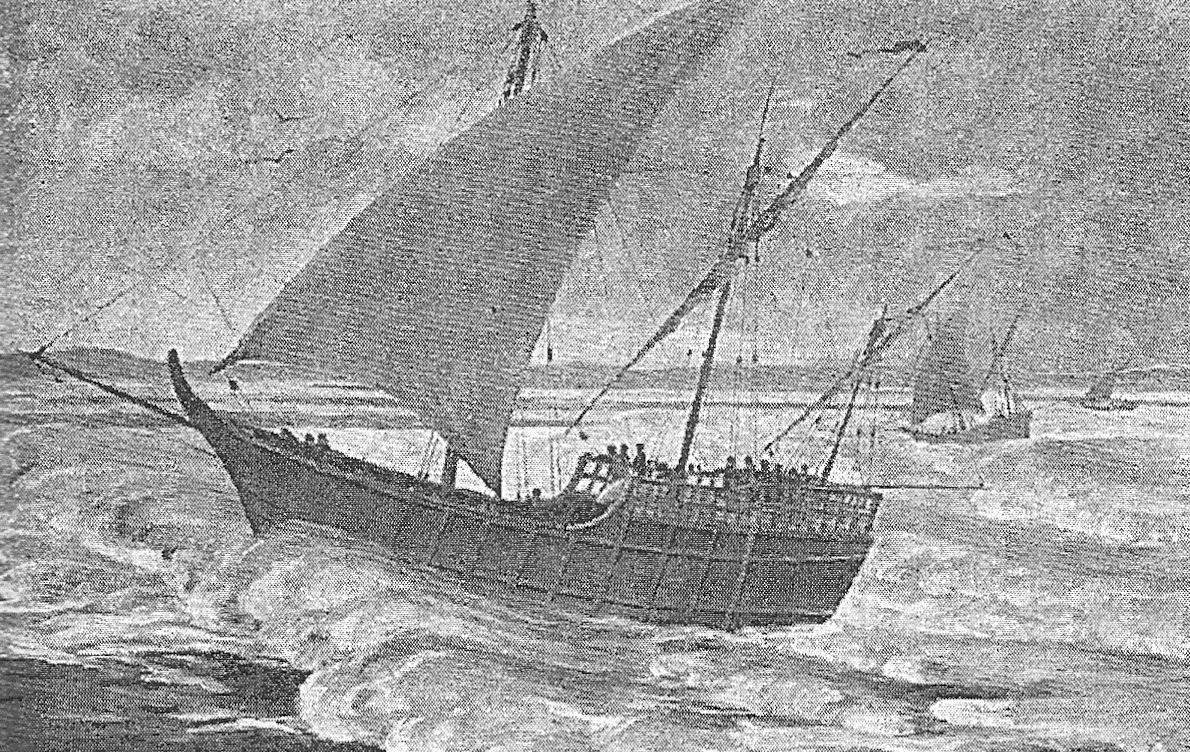

Spanish Galliot Sailing The Stormy Seas of The Gulf of California

Sailing The Gulf To Revive Baja Missions

Salvatierra's Third Letter

My Representative, Father Juan de Ugarte, P.C. [1]

I have not written you sooner because I am fully aware that the letters you desire are those sent from California. Through the mercy of the Lord, the intercession of Mary, and the protection afforded us by the Holy House of Loreto, which we came here to construct, this letter is being written to you from California. [2] In it I shall recount to Your Reverence our journey over land and sea. .... |91|

I reached Sinaloa during Holy Week. [3] The Spanish settlers interested all in assisting me in the task of planting the faith in California. From Sinaloa I set out for the Sierra de Chínipas and Guazapares in order to see all the Tarahumarans - my spiritual children - living in the mountains. [4] ... |92|

All this time I was soliciting supplies for the California enterprise. Inasmuch as the ships delayed, the missionaries in the mountains where I had once worked begged me to join them. Since it was necessary for me to wait, they insisted, I could help them and also share their perils. I acceded to their wishes, ascended again the mountainous area exposed now to the sudden attacks and assaults of the enemy. .... |93|

After the Feast of the Assumption, which we celebrated with great solemnity, I came down from the mountain fastnesses. ... I learned en route, from letters sent to me by Father Diego de Marquina, who lives on the Yaqui coast, about the arrival, on the eve of the Assumption, in the port of Yaqui of Captain Juan Antonio Romero de la Sierpe on board the galliot. [7] These letters also told me that the launch with eight persons aboard had disappeared during a storm along the coast of Barba de Chivato, but that a few days later it arrived safely in Yaqui.