Tumacácori

Kino's Mission San Cayetano de Tumacácori

Tumacácori National Historical Park

Living History at Tumacácori

26th Cabalgata of Por Los Caminos de Kino - December 27, 2013

Rideout Retracing Kino's 20 Hour Ride for Justice from Tumacácori to San Ignacio

Tumacacori National Historical Park Law Requires Recognition of Padre Kino

Public Law 101-344 101st Congress - August 6, 1990

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

Section 1. Tumacacori National Historical Park.

(a) Establishment.

.. there is hereby established the Tumacacori National Historical Park.

Section 2. Administration.

(d) Recognition of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino's Role.

In administering the park, the Secretary shall utilize such interpretative materials and other devices as may be necessary to give appropriate recognition to the role of the Jesuit Missionary Priest, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, in the development of the mission sites and the settlement of the region.

An Act Public Law 101-344 101st Congress August 6, 1990

United State Code

Title 16 Chapter 1 Subchapter LIX-Q

Tumacacori National Historical Park

16 USC 410 ss

Editor Note: On the eve of San Cayetano's August 7th saint's day, when Congress changed Tumacácori's status from a national monument to a national historical park, Congress further protected three Kino sites: Tumacacori, Guevavi and Calabasas.

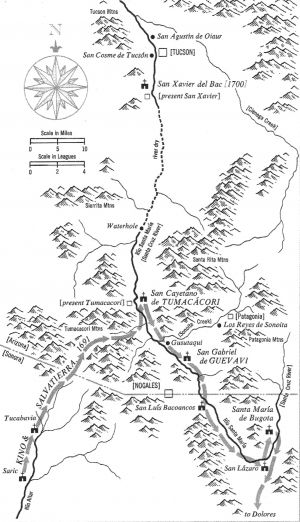

Map of Kino's Route to Tumacácori

December 1690 to January 1691

Kino's First Visit to Tumacácori On His First Major Expedition

Christmas Season 1691

A mighty stimulus was given to Kino's work by the visit of square jawed, hawk-nosed, and clear-headed Juan María de Salvatierra. Father Ambrosio Oddón had become provincial of New Spain for a Triennium. As visitor of Sinaloa and Sonora he appointed Salvatierra, who was still missionary at Chínipas, in the rugged mountains east of Alamos. At the same time Kino was made rector of his district, as successor to Father Muñoz. Father Oddón had heard many conflicting reports regarding Pimería Alta, so he sent Salvatierra to learn the truth. He was just the kind of man to find it. He had been, for ten years missionary in a most difficult field. He was a man of nerve equal to that of Kino. Before coming to Pima Land he made a perilous visit to war-torn Tarahumara where Fathers Foronda and Sanchez had recently been martyred. It was Christmas Eve when Father Juan rode up the hill from the south and dismounted at Dolores, just in time for the holidays, and he delighted Kino and his neophytes by conducting the Christmas services in the "new and spacious church," not yet completed.

This function over, Kino and Salvatierra set forth on a tour which occupied a month, and carried them into lands which neither one had ever seen. In the course of it they made plans which proved vital to both the Pimería and California, and determined Salvatierra's career. The travelers were equipped with pack mules, extra riding animals, and the necessary servants. First they went north to Remedios, which Kino was again taking under his personal care, "for the people were still much deceived because of the discord that had been sown against the fathers." Descending the canyon westward, they visited Father Sandoval at Imuris, and continued thence down the river. Beyond San Ignacio Kino was on new ground, and his eyes were wide open. We too are intrigued by these first glimpses of a new land.

They visited Magdalena, on the river, and El Tupo a little to the west, both in charge of Father Pineli. Swinging northwest now, they went ten leagues to Tubutama, on Altar River, where Father Arias was stationed. Here they found more than five hundred Pimas assembled, for Salvatierra's coming had been heralded. Among the throng were headmen from Chief Soba's tribe, that numerous people downstream to the west. While here the Feast of the Kings was celebrated and Kino preached from the text "Kings come from Saba"- Reges de Saba veniunt - a neat play on Chief Soba's name. We trust that Kino smiled at his own pun. With Soba's wise men from the West-Kino discussed the conversion of their people and promised to visit them later - más tarde. Continuing up the Altar, the travelers visited Saric and Tucubavia, where they counted more than seven hundred natives who, says Kino, "welcomed us everywhere with great pleasure to themselves and to us. Almost everywhere they gave the father visitor infants to baptize, and presented us with many supplies."

It was their intention to turn back now to Dolores by way of Cocospora, but a special circumstance changed their plans. At Tucubavia they were met by messengers from the north. In their hands they bore crosses. Kneeling before the Black Robes in humble veneration, they begged them to visit their villages also. Here was an appeal that could not be resisted. Salvatierra remarked to Kino that "those crosses which they carried were tongues that spoke volumes and with great force, and that we could not fail to go where by means of them they called us." So to the north the apostles reined their horses. Surmounting the divide in the vicinity of Nogales, guided by the messengers they descended to Santa Cruz River and there visited Tumacácori, a large Pima town nestling among the huge cottonwoods whose giant successors - or the same ones - still dispense welcome shade. The villagers had prepared three arbors or brush shelters for the visitors, "one in which to say Mass, another in which to sleep, and a third for a kitchen. There were more than forty houses close together." Some |265| infants were baptized, and Salvatierra promised fathers for the assembled natives.

Opponents had said that the new missionaries were not needed. But Salvatierra was convinced. "When his Reverence saw so many people, so docile and so affable, with such beautiful, fertile, and pleasant valleys, inhabited by industrious Indians," he said to Kino, "My Father Rector, not only shall the removal from this Pimería of any of the four fathers assigned to it not be considered, but four more shall come, and by the divine grace I shall try to be one of them." After the craggy mountains of Chínipas, the cottonwood groves of Arizona looked good to Salvatierra, and the gentle Pimas lost nothing by comparison with the lean-limbed and sensitive Tarahumares.

And now new evidence was added. Out of the north a band of warriors appeared at Tumacácori in full regalia. They were chiefs and headmen from the great Sobaípuri settlement of Bac, some forty miles beyond. They had come to urge the Black Robes to visit their people also. Bac was a metropolis; Tumacácori a mere village. But duty called Kino home, and Bac had to bide its time. So the apostolic pair swung sharply south up the Santa Cruz River to Guebavi, through the fine bottom lands of Bacoancos, now appropriately called Buena Vista, and around the great bend of the river, through San Lazaro to Santa Maria, a ride of fifteen leagues from Tumacácori, all the way through shady cottonwoods and beside a sparkling stream.

At Santa María Kino and Salvatierra spent five days baptizing infants and catechizing adults. Then they packed up their vestments and portable altar, promised to come again, and continued south over the live-oak hills and down the fertile river valley to Cocóspora. Here at the end of January they spent another five days catechizing, baptizing, and preparing a report to Father Oddón. It was now that the high-perched mission at Cocóspora was turned over to Father Sandoval. These things done, Kino and Salvatierra continued through Remedios to Dolores. This enlarged circuit - over two hundred miles - had taken Kino and his companion from the valley of the San

Salvatierra was deeply impressed with Pima Land. But something else impressed him still more deeply. As they rode side by side, up hill and down dale, Father Eusebio inspired his strong-jawed companion with a new and consuming ambition. "In all these journeys," Kino writes, "the father visitor and I talked together of suspended California, saying that these very fertile lands and valleys of this Pimería would be the support of the scantier and more sterile lands of California." The seed thus planted in Salvatierra's breast took firm root and grew to be a tremendous tree. Before saying goodbye, Father Juan urged Kino to undertake the conversion of both the Sobaípuris of the north and the Sobas of the west, "and with respect to California, even the building of a small bark in which to go there."

Dr. Herbert E. Bolton

"Rim of Christendom

A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino - Pacific Coast Pioneer"

Kino's 10 Year Campaign For The Return to The Californias

For the rest of the story, click

California Builder page

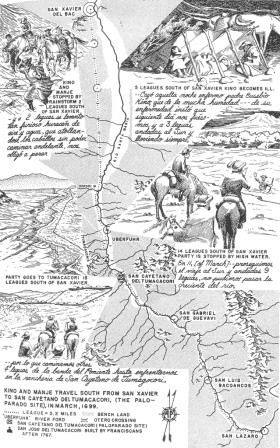

Kino Takes Ill on Return From First Colorado Expedition

Spanish Journal Entries from Captain Manje Writings

March 1699

O'odham of Tumacácori Come to Kino's Aid While Sick on the Trail

Kino nodded. The natives had brought him several of the big abalone shells this morning, the first he had seen since that long-ago trip to the west coast of California. Where had these come from? he wondered. Had traders brought them from the shores of the Pacific Ocean? Impossible to find the answer on this expedition, but perhaps the next time he came, he could make friends with the Indians farther down the river. Perhaps they would know.

The next morning they started east along the south bank of the Gila River. Again they traversed strange country, but it was a pleasant journey, always within sight of cottonwood trees, with plenty of water and pasture for the horses. In six days they were back in {132} Padre Kino familiar territory. On March 7 they were at San Xavier del Bac, where thirteen hundred people assembled to celebrate their arrival.

It rained that day, a heavy downpour that sent the river out of its banks and made seas of mud out of the roads. Padre Kino was happy to stay awhile and proud to show what the people of Bac could do. They had harvested and stored a hundred bushels of wheat in an adobe house. The cattle and horses had increased many times since Padre Kino brought the stock to them.

Two days later it was still raining, but Padre Kino insisted on leaving. Before they had gone five miles, a violent hurricane began to blow. The horses stopped in their tracks. It was impossible to go on. They spent a miserable night in the open and Padre Kino's fever returned. His feet and legs were swollen with rheumatism and Manje wished with all his heart that they were back with the friendly natives of Bac.

In the morning Padre Kino insisted that they go on. After a few miles, however, one of the servants shouted and Manje saw the padre leaning over his saddle horn, almost unconscious. By the time they got him off his horse, he had fainted. Hastily the Indians made camp and all that day Kino tossed on his blankets, nauseated,{133} fevered, his poor legs swollen so he could not find comfort in any position.

The next day he managed to swallow some medicine and keep it down; the pains left him and the swelling decreased. He was able to mount his horse and continue the journey. The river was too high to cross and they continued along the west bank until they came to a large village [of Tumacâcori]. The Indians brought over a sheep, butchered it and made some broth.

"He is so sick, so weak!" said one of them, looking sorrowfully down at Kino.

Manje frowned. Padre Kino was too ill to travel, but he could not stay out in the open. They pressed on, arriving at Dolores on the 14th of March. As they went into the church to thank God for bringing them safely back, no one was more grateful than Captain Manje. Yet no one looked forward with more eagerness than he to a second northwest expedition. Like Kino, he remembered only the good.

While Captain Manje was making his official report, Padre Kino was writing long letters to everyone he knew. At some time during that desperate ride from the Gila River, he had become convinced that in spite of Manje's objections, his own long-ago idea concerning {134} California was the true one. It was not an island. It was a peninsula!

He took the big blue abalone shells from the packs and compared them to the one he had brought from the west coast of California. Bigger than a man's hand, heavy, with a dark blue coating on the outside, and inside iridescent shades of brilliant blue and green winking up at him. They were the same. There was no doubt of it. These new ones must have been brought from the Pacific Coast by the strange white men the Yumas and Pimas had described to him.

California "was a peninsula," he could supply Salvatierra and his missions by driving stock around the head of the Sea. He must write Salvatierra at once. And he must tell the men of Caborca to stop work on the boat. It was no longer needed.

Jack Steffan

Padre Kino and The Trail to California

Editor Note: Kino on his first expediton to the Colorado River crosses the Camino del Diablo north to the Lower Gila River just east of present day Yuma, Kino is seeking to prove that Califonria is not an island and find a land route to supply the recently restarted Jesuit mission in Baja. Kino returns to Dolores by traveling east up the Gila River to Casa Grande and then south to Mission San Xavier del Bac arriving in March 1699. Later Kino will continue with building his boat in Caborca when he discovers in 1704 Tiburon and other Gulf of California islands and the possibility of a "sea and land bridge" across the Gulf of California.

Kino Rides 75 miles in 20 hours to San Ignacio to Save Man from Execution at Dawn

May 1700

Kino's Ride For Justice from Tumacácori

Padre Kino witnessed the turn of the 18th century at Dolores. His work load was heavy and the new California missions under Salvatierra were needing increased assistance. While Padre Eusebio was at Remedios, a chieftain from the Gila Pimas arrived with news of the river peoples and a cross strung with twenty blue shells, a gift from the governor of the Cocomaricopas.

With Easter season now over, he set out in late April with ten Indian friends – destination: the Gila pueblos…. He pulled up at San Xavier del Bac. With the question of the shells very much on his mind, he decided to send out inquiries about the origins of the blue shells. Runners went north, west and even east to call the great chiefs to a "Blue Shell Conference" at Bac. In a matter of days the Padre's messages got a response; chiefs and couriers came with the certain information that the blue shells from the Yumans could not have come from the Gulf because the blue-crusted abalone didn't occur in those dense waters. They had been traded hand to hand from the distant Pacific.

While waiting for the replies, Kino devoted his time to instructing the Sobaipuris in the catechism, and, true to his nature, he directed the laying of foundations for a large church. April 28 was the unforgettable day for the beginning of the church that has since transformed itself into an international memorial. As for Padre Kino, it was time to petition Father Visitor Leal for a permanent transfer to Bac which would place him much closer to the new mission field. He saddled up and rode south toward Dolores with a whole new future on his mind.

At dawn on May 3, Kino was preparing to say Mass at San Cayetano de Tumacácori when he was handed a letter from Father Campos at San Ignacio. It was an urgent summons for him to intervene in the scheduled execution, May 4, of a prisoner in the custody of the soldiers. Riding until midnight, he rested at Imuris, reaching San Ignacio at sunrise – just in time to celebrate Mass and save a poor Piman from death.

Such was Kino’s whole life in the saddle – long treks in the desert, rapid rides in the cause of justice and mercy, and tedious journeys bringing food and supply to distant Indian tribes; there was no casual rest for the Apostle to the Pimas.

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

Kino; A Legacy ....

The Blue Shell Conference & Kino's Ride for Justice

To View and Download Two Accounts

"A String Of Twenty Blue Shells Give The Final Clue"

"Kino as a Practical Man of Affairs"

Chapters from pp 82-86; pp 133-138

Frank C. Lockwood

To view and download the entire Frank C. Lockwood, click →

https://uair.library.arizona.edu/system/files/usain/download/azu_h9791k55z_l81_w.pdf

"Blue Shells - Bother or Boon?"

Chapter from "Kino: A Legacy" pp 68-70

Charles W. Polzer

Click Blue Shells Polzer document (text)

Four Accounts of Kino's First Visit

Herbert E. Bolton

From "Rim Of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino - Pacfic Coast Pioneer"

For English, click Bolton Tumaccori Visit document (text)

For Spanish translation, click Bolton Primeria Visita a Tumacacori document (text)

Frank C. Lockwood

From "With Padre Kino On The Trail"

Click Lockwood Tumacacori Visit document (text)

Charles W. Polzer, S.J.

From "Kino - A Legacy: His Life, His Works, His Missions, Him Monuments" 1998

Click Polzer Tumacacori Visit document (text)

Jack Steffan

From "Padre Kino and the Trail to the Pacific" -

a very accurate historical novel account based on Kino's writings

Click

Steffan Chapter 3 - Among the Pimas page

Tumacácori Living History

Por Los Caminos de Kino Cabalgatas

Tumacácori Rideout Retracing Kino's Ride for Justice

Blessing Pilgrims and Their Horses

26th Cabalgata of Por Los Caminos de Kino - December 27, 2013

Tumacácori Ride-in

2nd Cabalgata of Por Los Caminos de Kino - December 30, 1988

Pilgrimage on Horseback from Dolores to Mission San Xavier del Bac

Ride to Kino's Guevavi Mission Ruins

2nd Cabalgata of Por Los Caminos de Kino - December 29, 1988

Left - Dr. Gabriel Gómez Padilla - World's Leading Kino Scho

Por Los Caminos de Kino - 35 Years of Kino Cabalgatas

The members of Por Los Caminos de Kino promote the enduring legacy of pioneer Jesuit missionary and explorer Padre Eusebio Kino and the cause for his sainthood. The activities of the association since 1987 have ranged from its 28 living history Kino Cabalgatas to publishing books & producing online multimedia about Padre Kino. To access the Association's multimedia, click Kino Video.

The Association’s name Por Los Caminos de Kino can be translated into English as “Following Kino’s Way.” The meaning of the name not only refers to the Kino Cabalgatas where the members make pilgrimages on horseback by following the past trails of Kino. It also refers to following the example of Kino’s life & his teachings as a guide to living a better life.

The past cabalgatas followed Kino's journeys across the deserts, mountains, rivers and coasts in today''s states of Arizona, California, Sonora, Sinaloa, Baja California del Sur and Baja California del Norte.

In 1996 the organization rode the Anza Historic Trail from Hermosillo to San Francisco to commemorate Kino's vision of a seaport on the Pacific coast. Kino's vision of a California seaport was fullfilled when the settlers of the Anza Expedition founded San Francisco in 1776 - 65 years after Kino''s death in 1711.

For more information about Por Los Caminos de Kino and maps of its 29 cabalgatas, click Kino Pilgrimage Section Page page.

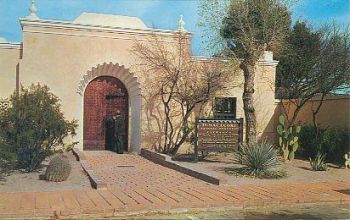

Visitor Center Entrance with Kino Mission Designs

Shell Portal of Mission Cocóspera

Replica Carved Doors of Mission San Ignacio

Tumacácori Visitor Center Replicates

Architecture Elements of Kino Missions

Tumacácori National Historical Park

Many authentic architectural quotations came from specific examples that were recorded in Sonora: The shell motif over the main entrance is a copy of that at Mission Cocóspera; the carved wood entrance doors are replicas of those at Mission San Ignacio; the carved corbels and beamed ceiling in the lobby are inspired by those at Oquitoa; the piers and arches in the patio are based on those at Caborca; and the groin-vaulted ceiling in the view room got its inspiration from Tubutama and other Sonoran missions. The wooden grill work on the west office window was copied from the choir loft at Tubutama (Bleser 1989,41). DeLong's full size details for some of these features are preserved at the NPS Denver Service Center. He served as architect for the building.

Buford Pickens, FAIA

Editor's Introduction

"The Missions of Northern Sonora: A 1935 Field Documentation" 1993

The Annual Fiesta de Tumacácori

First Weekend of December

The Fiesta [de Tumacácori] grew out of the commemoration of the first Mass held at Tumacácori by Father Kino a few weeks later in January 1691 .. Even though the commemorative Mass evolved into a full-blown Fiesta in 1972, the Mass has always been a key element of the Fiesta and has always been in memory of the first Mass Kino celebrated there. The first commemorative Mass in 1965 marked 275 years since the time Kino celebrated the first Mass at Tumacácori.

"An Interview with Bernard L. Fontana"

Sonárida

January - June 2010 Number 19

Editor Note: The Fiesta de Tumacácori is hosted by the Tumacácori National Historical Park and is held annually on the first weekend in December.