World Famous Map Maker

Kino Cartographer

Kino's Maps

Displayed in Reverse Chronological Order

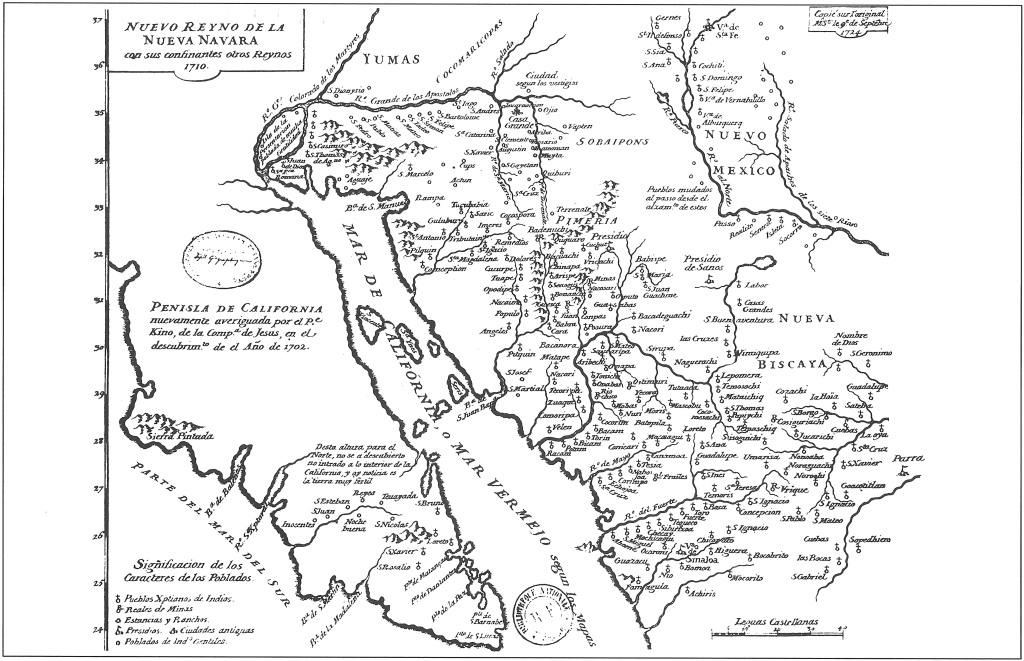

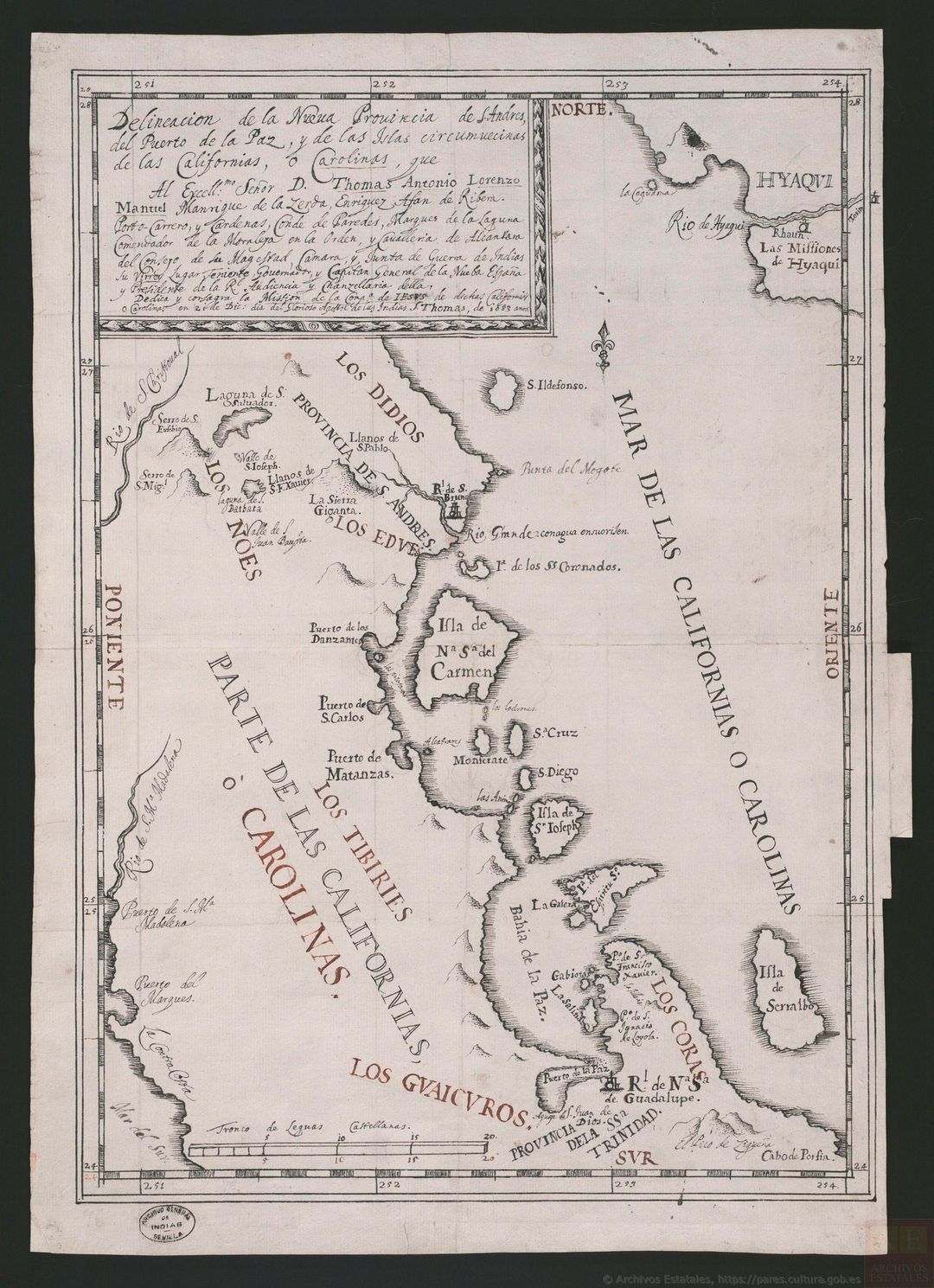

Nueva Reyno de la Nueva Navara

Northern New Spain 1710

Kino's Contributions to World Cartography

Ernest J. Burrus

By way of introduction to a better appreciation and understanding of Kino's contribution to the cartography of northwestern New Spain, it should prove helpful to recall the motive inspiring this phase of his work and observe a few of the characteristics common to all his maps.

For Kino a map was not merely a visual aid to understand a geographic reality, nor an independent graphic expression, but rather an effective illustration and helpful complement to his letters, reports and even lengthy diaries. His cartographical productions recorded his explorations as faithfully and as scientifically as his written word; as I shall have occasion to discuss, his last map reflects much that his pen did not have time to record.' The decisive advantages of maps over every other form and means of expression at his disposal inspired Kino to delineate the most numerous and significant cartographical series in the history of New Spain.

Kino felt the need of a map to give fuller and clearer expression to his thoughts. Thus, he added a map to the diaries of his overland journeys and sea voyages. Even in the allied excursion into astronomy, he charted the heavens to illustrate every point discussed in his written treatise." He helped build a chapel in San Bruno, Lower California, and assisted in constructing a protective fort for the small settlement; he was not content with writing to ecclesiastical and royal officials about them, nor with telling friends and benefactors that at long last a permanent foothold had been secured in California. No, he wanted all to "see" more fully the great reality; accordingly, he sketched the fort, chapel, dwellings, and even the small cannons."

This need that Kino felt for the more graphic expression furnished by a map, is evident even from his preaching. In the autumn of 1692 he was in the principal rancheria of San Xavier del Bac. "I spoke to the Indians of the word of God, and on a map of the world pointed out to them the lands, the rivers, and the seas over which we missionaries had come from afar to bring them the saving knowledge of our holy faith. I also told them how in ancient times the Spaniards were not Christians, how Saint James came to teach them the faith ... I showed them on the map of the world how the Spaniards and the faith had come by sea to Vera Cruz, and reached Puebla, Mexico City, Guadalajara, Sinaloa, Sonora, and now Nuestra Señora de los Dolores del Cosari, their own homeland, the country of the Pimas, where there were already many baptized, with the missionary's house, church, bells and images of the saints, abundant supplies, wheat, corn, and many cattle and horses. I assured them that they could go and see it all, and even ask at once of their relatives, my servants, who were with me. They listened with pleasure to these and other talks concerning God, heaven and hell, and told me that they wanted to become Christians."

It is significant that in all his maps the human element holds the first place. It is not the mountains, rivers, bays, nor the vast expanse of the plains, not so much the native settlements nor even the missions themselves which are of primary interest to Kino; it is the people. The names of their groups or tribes are written in the largest letters across his charts and in color. Even the geographic features are thought of and represented in relation to the inhabitants, villages, and groups of people. The missions serve the people. The cattle ranches and farms support the people. The rivers are referred to as means of communication between peoples; several are designated as "thickly populated," in the sense that in the valleys watered by them many people can dwell. Even the water holes are marked with the same psychological attitude: they are the indispensable minimum to allow the missionaries and travelers to come to the people; they are the difference between life and death for the people themselves.

Kino's maps are progressive in the sense that they are chronologically ever more inclusive and more accurate, eliminating earlier misconceptions, his own and those of others. ...

The proof of the peninsularity of Lower California and the mainland character of Upper California is merely one of Kino's many contributions to the geography and cartography of the north western frontier of Spanish America. It is Kino's best known discovery, or more correctly, his most widely publicized rediscovery.

Often overlooked are his numerous other contributions of a similar nature and of no less importance: the relative position of the main Colorado and Gila rivers; the correct location of the upper Sonora and lower Arizona streams, valleys and mountains; the rediscovery of the insular nature of Tiburon; the pioneer discovery of the Angel de la Guarda Island; a far more exact location of the Rio Grande del Norte flowing from New Mexico and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. Most important, Kino prepares the way to rid Spanish American geography and its expression in world-wide cartography of the endless designations of non-existent, vague and shifting features and elements......

Kino's 1701 map, first printed in 1705 and reissued so frequently and in so many different languages, deservedly brought him wide recognition as an explorer and cartographer. All the printed versions of this map with which I am acquainted, credit Kino with his authorship. Although the one manuscript copy of the 1710 map derived directly from the original likewise attributed the chart to Kino, all subsequent versions, printed and manuscript, omitted his name.

Little or no doubt, however, was entertained about its essential accuracy. If Kino's name was omitted, the unique nomenclature he chose shortly before his death invariably revealed the ultimate source as unmistakably as if he had signed every copy, adaptation and imitation with his own signature. Guillaume Delisle [1722], D'Anville (in whose collection I found the 1724 copy), Bonne [1780], Tomás López [1758], William Robertson [1796], Lewis , Humboldt [ 1822], Alzate [1768], García Cubas [1885]: these are the geographers, cartographers and historians who gave Kino's 1710 map currency throughout the European and American world of learning. If any of them doubted its accuracy he could have found manuscript ccopies in the key Spanish and French government collections....

The chart [Kino's 1710 Map] was reproduced with great accuracy by the world's outstanding map-makers, geographers and historians, with the result that for over a century and a half it was the standard cartographical representation of northwestern Spanish America and southwestern United States. ...

Of all the missionaries who came to the New World - whether they worked in New France, Brazil or in the more extensive Spanish dominions - Kino was the best prepared scientifically to delineate accurate maps of the areas where he carried on his intense activity.

Ernest J. Burrus, S.J.

"Kino and the Cartography of Northwestern New Spain." 1965

Editor's Note: dates of the maps pirated from Kino's 1710 map are added to the text as discussed in the book.

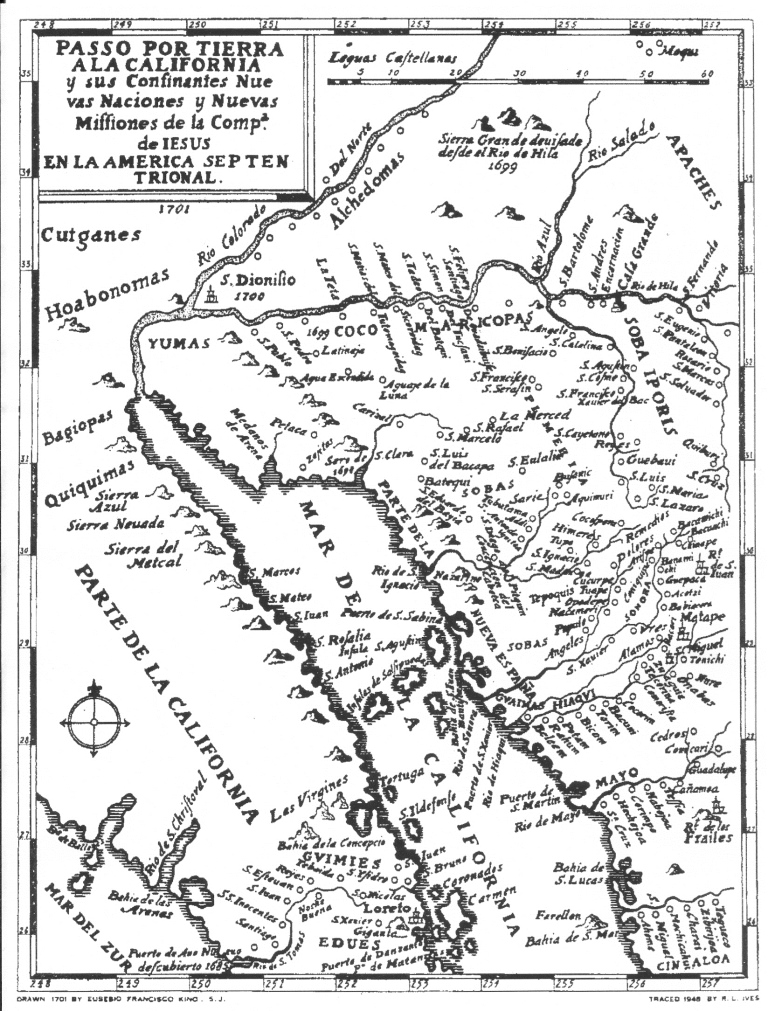

Passos Por La Tierra a la California

Kino's Most Famous Map 1701

First Map Showing Baja Connected to the Continent Based on Exploration

California No Es Isla

The idea in the early 1600s that California was the largest island in the world and located west of the North American continent was a product of speculation, imaginative fables including English privateer Francis Drake's accounts of sailing around the island. The world of geographers seized upon the idea, and almost for two centuries hundreds of maps were published depicting California separate from the mainland.

The idea persisted because it was almost impossible to explore the Gulf of California by sea or the Lower Sonoran Desert by land. After the Blue Shell Conference at San Xavier Mission called by Kino and his many trips into North America's equivalent of Africa's Sahara Desert to the Colorado River, Kino determined that California was connected to the mainland and wrote in his reports "California no es isla". His discovery was very important because the possilbe land route could encouraged the return of the Jesuits to the Baja and provided the prospect that Kino's bountiful missions of the Pimeria Alta could reliably and inexpensively support the barren missions of Baja.

Because Padre Kino had only observed the connection on land at the end of the delta, his maps were disputed for over 40 years until In 1746 Ferdinand Konsag sailed completely around the Gulf of California to confirm that Baja California was connected to the mainland. A year later the Spanish King issued a royal decree declaring that "California is not an island." in the 1770s.

The Spanish settlement of the modern state of California would have been much more difficult without the efforts of Kino. It was very difficult for the Spanish to sail to California from Mexico because of countervailing winds and ocean currents and the devastation the scurvy on the sailors. Overland routes from Mexico via the Baja penisula and across the Sonoran Desert were California's lifeline.

Kino was a constant advocate for the Jesuit return to Baja after he and Atondo colonization effort ended because of possible starvation. Fourteen years after Kino left, Padre Salvatierra returned and Kino's Sonoran missions provisioned him.

Sixty years later California was settled by the Spanish by the Portola Expedition traveling up the Baja mission chain to San Diego and the Anza Expediion using trails that Kino blazed across the Sonoran Desert to settle the San Francisco Bay.

Kino and the Cartography of Northwestern New Spain

Enrest J. Burrus, S.J.

Passos Por La Tierra a la California

Kino's 1701 Map

The U.S. Congressional Record 1878

"A map of the greatest importance in the history of Arizona and of California accompanies this memoir. This map is entitled entitled 'Passage par terre à la Californie déconert par le Rév. Pére Eusébe Francois Kino, Jésuite, depuis 1698 jusqu'à 1701, où l'on voit encore les Nouvelles Missions des P.P. de la Compagnie de Jésus."

The map of Father Kino is not only very important on account of its giving with considerable accuracy the head of the Mer Vermeille, or Gulf of California but at locating and showing a great number of the villages, missions, pueblos, rivers and mountains of Sonora and of New Mexico (the part now known as Arizona) and of Lower California, or, properly, Old California.

Professor Jules Marcou

"Notes Upon the First Discovery of California and Origin of Its Name"

Annual Report of Lieutenant George M. Wheeler, Corp of Engineers

Executive Documents of the House of Representatives 3rd Session 45th Congress

Report of the Chief Engineer 1878

Editor Note: Kino's 1701 Map set out opposite page 1649 in The U.S. Congressional Record.

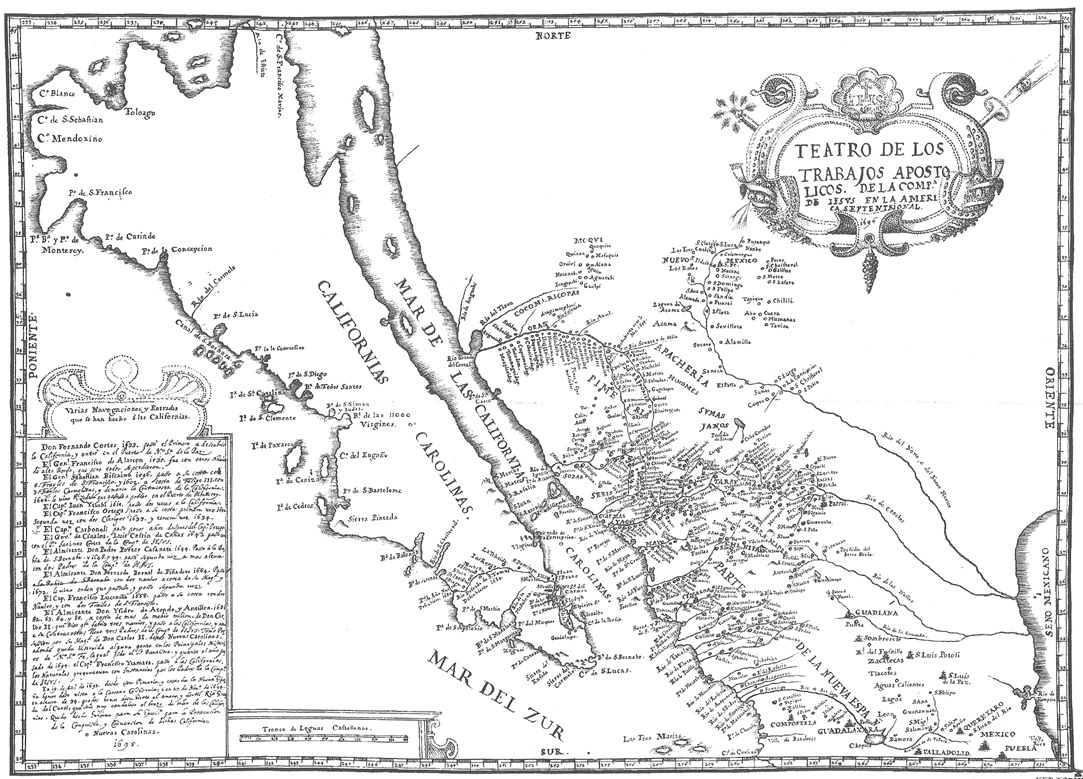

Father Saeta Map 1696

With Kino's Drawing of Father Saeta's Death

Teatro de Los Trabajos Map Illustrating His Saeta Biography 1695

With Kino's History of Previous Attempts To Settle The Californias

Kino's History of Previous Attempts To Settle The Californias

Teatro Map Text

Eusebio Franicsco Kino

Teatros de los Trabajos Apostólicos de la Compana de Jesús en la America Septentrional 1695

Various sea expeditions and entrances

made into the Californias. |39|

Don Fernando Cortéz set out in 1533 as the first to discover California, landing at the port of Nuestra Señora de la Paz. General Francisco de Alarcón went in other high-decked ships; all of which, however, were lost. |40|

General Sebastián Biscaíno went there in 1596, at his own expense with five Friars of Saint Francis; and in 1602, at the expense of Philip III, with three Carmelite Friars he explored the west coast of California. In 1606 he received a royal decree ordering him to found a settlement in the port of Monterey. In 1615 Captain Juan Iturbi made two expeditions to California.

Captain Francisco Ortega crossed over to California the first time in 1632; this he did at his own expense. The second time (in 1633) he took two clerics with him. His third expedition was in 1634. |41|

Captain Carboneli undertook his expedition a few years after Captain Ortega. The Governor of Sinaloa, Luis Cestín de Canas crossed over in 1642, taking with him Father Jacinto Cortés of the Society of Jesus.

Admiral Don Pedro Porter Casanate disembarked in 1644 in the bay of San Bernabé; and in 1648 and 1649, taking with him two Fathers of the Society of Jesus, he made a landing further north. In 1664 Admiral Don Bernardo Bernal de Piñadero made an expedition in two ships at the expense of his Majesty, and in 1672 he received orders to make a second expedition, which he did.

In 1668 Captain Francisco Lucenilla made an expedition in two ships at his own expense, taking with him two Friars of Saint Francis. |42| Admiral Don Isidro de Atondo y Antillón in 1681, 1682, 1683, 1684 and 1685, at the cost of more than a half million pesos furnished by Don Carlos II (whom God protect), built three ships, and crossed over to the Californias and even to the opposite shore. |43|

He took with him three Fathers of the Society of Jesus. He took possession of these New Carolinas for Don Carlos II. Some of the inhabitants were instructed in the principal doctrines of the faith and are pleading for holy baptism; last year (1694), when Captain Francisco Itamarra (Yramara) went to the Californias, the natives asked most insistently for the Fathers of the Society of Jesus. On December 19, 1693, we beheld from this land of the Pimas and coast of New Spain the nearby region of California: and again on November 27, 1694, at the thirty-fourth parallel, we discovered the pleasant and productive Río Grande del Coral which pours its vast volume of water into the arm of the Sea of California. I have compiled a report for his Excellency in order to reactivate the conquest and conversion of the said Californias or Carolinas. 1695."

History of California Exploration by Eusebio Franciso Kino.

Translation by Ernest J. Burrus

Editor Note: Title and text about the history of the Spanish attempts to settle the Californias in Kino's handwriting together with his cartography. This map accompanied the "Biography of Padre Saeta" and was personally presented to the highest officials in Mexico City by Kino after he rode 1,500 miles in 53 days. Kino began his ride for peace and justice on November 16, 1695 from his Mission Dolores headquarters in order to protect the O'odham people from reprisals and to advocate for a renewed Jesuit effort in the Californias.

California, A Peninsula Or Island?

Ernest J. Burrus

lsewhere I have devoted hundreds of pages to this topic which claimed the attention of so many explorers and missionaries of the time. Obviously, the hotly debated subject is reflected in our present reports. The reader interested in following the fascinating attempts at solving the problem can consult numerous references in our Bibliography. Here I shall merely outline the origin of the problem and the efforts made to solve it.

The earliest explorers, Cortés and companions, Ulloa and Alarcón, had no doubt about the penisularity of the region. They either sketched Baja California with open boundaries - such is the first map we have of the land, that by Cortés - or very clearly and accurately depicted it as a peninsula - such is Alarcón's map. So, too, all succeeding explorers and cartographers delineated the region as it really is. As a peninsula, it entered world geography and cartography.

No one ever thought of challenging this conviction until the Englishman Henry Briggs published Fray Antonio de Ascensión's map in 1622. Ascension, the Carmelite cosmographer who accompanied Sebastián Vizcaíno on his second expedition along the west coast of the Californias, was the first to claim that they constituted an island. He made his contention worthwhile: not only was Baja California an island but also the contiguous Upper California to nearly forty-five degrees. Thus was California made an island - the largest island in the world.

The ship carrying to Spain Ascensión's truly revolutionary map was seized by English pirates. It got into the hands of English publishers who issued repeated versions of Ascensión's data and map. Even Spanish cartographers, who should have known better, were deceived.

Kino, whose professors Adam Aigenler and Heinrich Scherer had taught him that California was a peninsula, came to Mexico holding a correct view regarding the land he was appointed to explore and map. But during his long stay in Mexico City (1681-1682) he was convinced by Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, Mexico's most eminent scientist at the time, who lent him numerous maps showing the region as an island, and changed his opinion. From 1683 to 1698 he depicted Baja California as an island. His first great expedition from Dolores in Pimería Alta to the vicinity of the head of the Gulf of California in 1698 convinced him of its peninsularity. That year he drew an accurate map of the northwestern Mexican mainland and the adjacent peninsula. It entered world cartography in 1705 when it appeared in two French publications. Kino carried out numerous subsequent expeditions to confirm reality.

It was less for theoretical than for very practical reasons that he wished to prove the peninsularity of Baja California. As we have seen, the missions there depended for their very existence on the cattle, food and other supplies reaching them from the mainland; but shipping across the stormy gulf was both expensive and precarious. Hence, Kino was anxious to find a safer and less costly land route from his missions on the continent.

Not all accepted his revolutionary concept about the nature of the region. It was not until about 1820 that the last critics gave up their opposition and Kino's version was universally accepted. Ironically, even had everyone agreed with Kino from the very beginning (1698), it would not have been possible to take advantage of the land route to the peninsula. Even today no such passage is feasible.

Ernest J. Burrus

California, A Peninsula Or Island?

Introduction

Jesuit Relations, Baja California, 1716 -1762

Baja California Travels Series, Volume 47, 1984

Padre Kino 1685 Gulf of California Map

Padre Kino 1685 Gulf of California Map

Before His Entrada into Pimería Alta

This map published in Europe was based on Padre Kino map drawn in 1685. It shows the lower part of the Baja California peninsula with information acquired by the Atondo-Kino expeditions including the first European crossing of Baja California (December 1684- January 1685). The approximate route of the first crossing was along a line that is slightly below latitude 26 degrees on Kino's map. Kino and the members of the expedition started at San Bruno on the Sea of California and then climbed over the La Giganta Mountains to the headwaters of the Rio de San Thomas (now Rio La Purisima). They then followed the drainage of the Rio de San Thomas to Gregorio Point on the Pacific Coast (not shown on Kino's map). For Map of Kino's route, click Exploration Baja & Gulf of California document (text)

The map also shows existing missions and settlements on the Mexico mainland before Padre Kino made his entrada into the Pimería Alta which he started from Cucurpe. This map was redrawn and published in Europe in 1703 during Kino's lifetime and included in a famous world atlas.

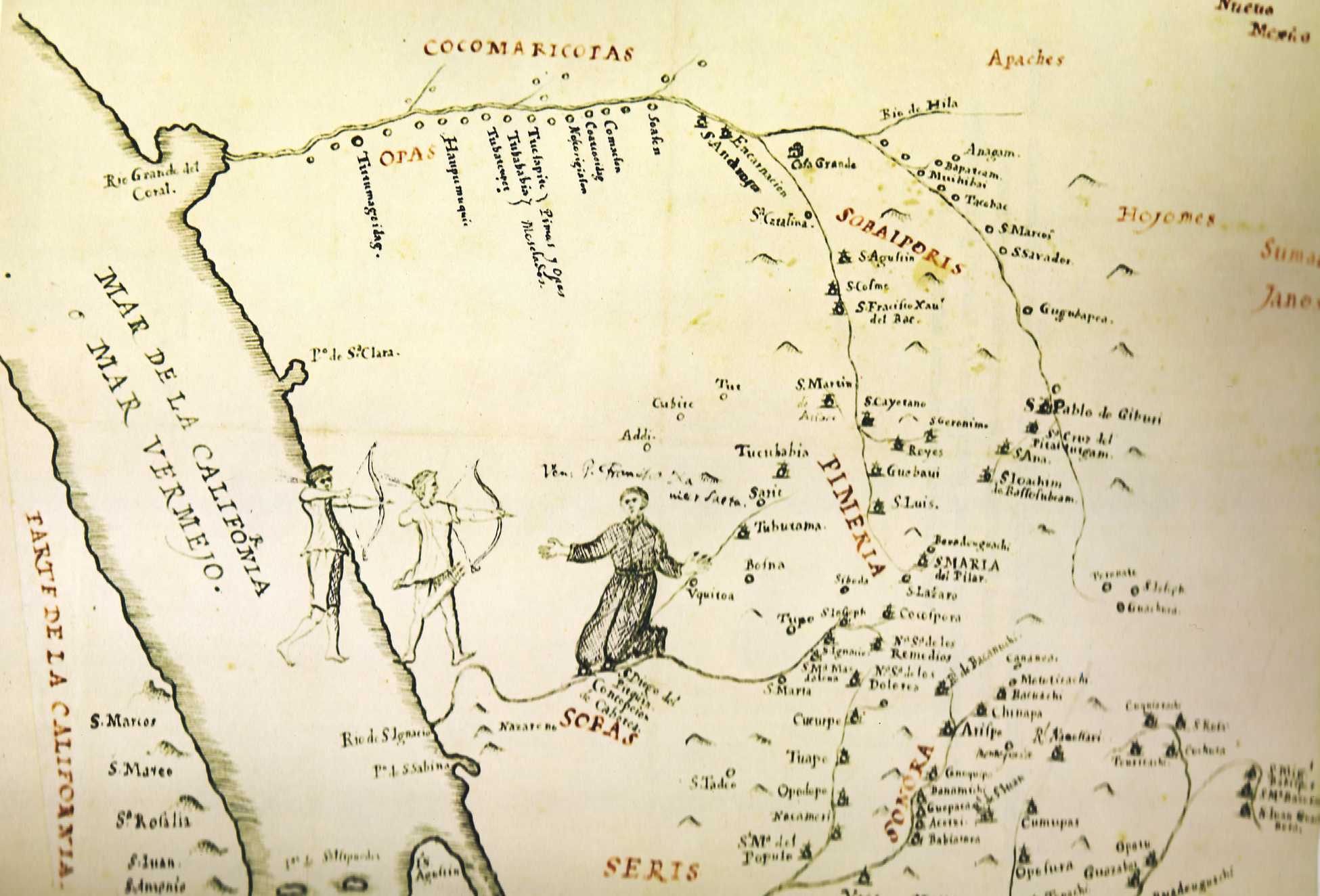

Kino Map of California and Its People 1683

California No Es Ysla ...

Ronald L. Ives

Maps of western North America, prior to about 1700, were an unhappy mixture of fact and fancy, their content suggesting that inadequacies in available data were filled in by plagiarisms from Pliny and Pedro Martyr, with a few misunderstood Indian legends included for good measure. Typical of these early maps is that by Johanum Ogiluium (John Ogilvie), circulated in England about 1680. Here we find the west coast bordered by a large body of water -- the Strait of Anian -- across which is the island of California. From this and other maps of about the same date, many erroneous ideas of the coastline of North America were gained. This misinformation was particularly insidious because the same maps contained many correct and easily verifiable features.

Some of these fanciful geographies can be attributed to mistranslation of Indian narratives, so that tribal mythologies were interpreted as facts; some may have been due to mirages, still common on the shores of the Vermilion Sea (now the Gulf of California); and many were just plain lies, told by travelers to impress a credulous public.

Shortly after 1705, maps of western North America suddenly changed, and the mythical Strait of Anian, in company with many other imaginary features, was no longer found between what is now Arizona and our present state of California. In its place, the Colorado and Gila Valleys are shown with considerable accuracy, and the peninsular nature of Baja California is clearly shown. D'Anville's map, "Amerique Septentrionale," published in Paris in 1746, is an excellent example of these later maps, from which "lakes of quicksilver and of gold, etc." have been eliminated.

The cited maps represent the majority opinion in their respective periods. Some earlier maps did represent California as a part of the mainland of North America; and a few later maps show it as an island. The earlier "dissenters" apparently based their opinions on unproved data, such as accounts of the explorations by Melchior Diaz (1540-41) and' others; later "dissenters" chose to disregard plentiful convincing evidence.

Extensive field and library investigations disclose that most of the early maps (ca. 1700) showing Lower California as a peninsula, and Alta California (the present state) as a part of the mainland of North America, are based on the work of one man -- Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. -- who, almost single-handed, produced incontrovertible evidence that California was not an island, but a part of the mainland. This evidence is summarized in his map "Passo Par Tierra a la California," drawn in 1701. A copy of this cartographic masterpiece, which is one of the most important maps in the history of North America, comprises Figure 1.(1)

So accurate is this map that no important part of it was superseded for more than a century and a half, and remapping of the entire area was not completed until the second decade of the twentieth century. (2)

For entire article, click on California No Es Ysla document (pdf)

Ronald L. Ives

"California no es Ysla ..."

Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia

December 1953 Vol. LXIV

Pages 189- 198

Editor Note: This article was written one year before Kino's 1710 map was discovered in an archive in the National Library of Paris in 1962 by Ernest J. Burris, S.J.

Determining Latitude

Eusebio Francisco Kino

At noon we reckoned the height of the sun (pessamos el sol) with an astrolabe, and I found (ha!le) it to be at fifty-two degrees. To this I added six and a half degrees to compensate for the south declination of the day, thus arriving at a total of fifty-eight and a half degrees. Now, the complement of this to make ninety degrees is thirty-one and a half degrees, which is the altitude of the pole or the geographic latitude of the place where we were."

Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J.

Enrty in Kino's Field Diary

March 3, 1702

Latitude sighting at the junction of the Colorado and Gila Rivers.

Navigation Methods of Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J.

Ronald L. Ives

One of our treasured legacies from the Jesuit mission era is the beautiful and famous map "Passo por Tierra a la California," drawn in 1707 by Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J., known to history as "The Apostle to the Pimas": maker of Christians and builder of missions. So accurate is this map that it did not become completely obsolete until 1912, when Lumholtz' map "Papagueria" was published.

As might be expected, the Kino map was widely circulated and widely plagiarized during the early eighteenth century, so that many versions, many of them not credited to the original author, are now extant. Checking of this map against the best available today shows that all major features of Papagueria are shown in their correct inter- relations to a rational scale ("Leguas Castellanas"), that the latitudes are all correct to less than a degree of arc, and that the longitudes are all in reasonable proportion. And, as will be shown later, Kino had no way of making rigorous longitude determinations.

Field checking of the may amply demonstrates its practical utility.Almost any reasonably intelligent person using this map - and, in a few instances the descriptions from Kino's notes," or the substantially parallel Manje notes" -can recover any site shown on the map, usually within a few hundred feet. This was actually done by the late Herbert E. Bolton in retracing hundreds of miles of Kino's trails; and the present writer has had equal success in the lavas and sand dunes around Pinacate, where Professor Bolton did not go.

Ronald L. Ives

"Navigation Methods of Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J."

Arizona and the West (Journal of the Southwest)

Autumn 1960 Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 213-243

For entire article, click on Kino's Navigation Methods document (text)

Note: This article was written one year before Kino's 1710 map was discovered in an archive in the National Library of Paris in 1962 by Ernest J. Burris, S.J.

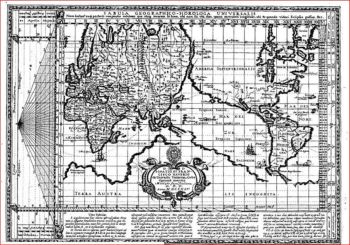

World Map by Adam Aigenler, S.J.

Kino's Cartography Professor in Europe

Aigenler's World Map Shown by Kino To The Sobaípuri People

Kino's First Sermon with World Geography

Mission San Xavier del Bac 1692

"I spoke to them of the Word of God, and on a map of the world showed them the lands, the rivers, and the seas over which we fathers had come from afar to bring them the saving knowledge of our holy faith. And I told them also how in ancient times the Spaniards were not Christians, how Santiago came to teach them the faith, and how for the first fourteen years he was able to baptize only a few, because of which the holy apostle was discouraged, but that the most holy Virgin appeared to him and consoled him, telling him that the Spaniards would convert the rest of the people of the world."

"And I showed them on the map of the world how the Spaniards and the faith had come by sea to Vera Cruz, and had gone in to Puebla and to Mexico, Guadalajara, Sinaloa, and Sonora, and now to Nuestra Senora de los Dolores del Cosari, in the land of the Pimas, where there were already many persons baptized, a house, church, bells, and images of saints, plentiful supplies, wheat, maize, and many cattle and horses; that they could go and see it all, and even ask at once of their relatives, my servants, who were with me. They listened with pleasure to these and other talks concerning God, heaven, and hell, and told me that they wished to be Christians, and gave me some infants to baptize. These Sobaipuris are in a very fine valley of the Rio de Santa Maria, to the west."

Eusebio Francisco Kino

"Journey Northward To The Sobaípuris"

"Favores Celestiales"

August 23, 1692

Kino's Maps Best & Most Published

Como se señaló, a diferencia de los elaborados por otros misioneros jesuitas, los mapas de Kino fueron los que de mejor manera expresaban los conocimientos cartográficos del momento, los de mayor precisión en tanto fuentes de información, y por ello mismo, los más reproducidos en la Nueva España y en Europa.

[As noted unlike those produced by other Jesuit missionaries, the maps of Kino were those that best expressed the cartographic knowledge of the time, the most accurate as sources of information, and therefore, the most reproduced in New Spain and in Europe.]

Pedro Damián Martínez Castillo

La cartografía jesuita de la provincia de la Nueva España

EstudIos Jaliscienses # 93

Agosto de 2013

Spanish Royal Ordinances Governing Discoverers and Their Explorations

Law of Indies 1573

Jorge Olvera

|170| Philip II, for his part,wished to avoid disorderliness when he published his Ordenanzas Reales (Royal Ordinances) in his Leyes de Indias (Laws of the Indies) on July 13, 1573. These ordinances prescribed a series of steps to be taken in creating settlements in the recently conquered lands. ...

It is possible to discern how closely Kino followed the Ordenanzas Reales as soon as he was authorized by the Spanish crown, through viceregal authority and his religious superiors, to found new missions in the Pimeria Alta. Kino, especially as the discoverer and settler of what to Spain were new and unknown lands, was expected strictly to adhere to Las Leyes de Indias.

|171| Ordinance Number 1 stated: “No person, without our authorization, can make a new discovery, nor entry, nor establish a new settlement, hamlet or camp or rancheria in that which is already discovered, under penalty of death and confiscation of property; but in that which is already discovered, the governors can authorize whatever new settlements that are convenient, sending us a descriptive account of it as soon as possible.”

Under Spanish law, Kino became 1) a discoverer, 2) an adelantado, or the advanced governor of a province to be discovered, and 3) a missionary for the spreading of the Gospel.

Ordinance Number 14 said, "The discoverers with the officials will name all the land discovered, [including] each province and the mountains and most important rivers."

Accordingly, Kino named the region the Pimeria Alta and proceeded to name its rivers, mountains, and Indian settlements. In naming the latter, he preserved the Indians' names for their own communities, joining them with a Christian name and thereby bestowing Christian patron on the village. He did this when he added the Christian name Santa Maria Magdalena to the Indian settlement of Buquivaba (Santa Maria Magdalena de Buquivaba). From his diary, we know he did the same for dozens of other places, including Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Cosari (or de Bamotze), Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocospera, San Xavier del Bac, and San Pedro y San Pablo del Tubutama.

Like a new Adam who was given the privilege by God of naming everything in the newly created paradise, Kino also labelled the rivers, mountains, and even such sites in the desert as water holes or sandy areas.

Ordinance Number 26 shows the importance placed by the Spanish crown on members of religious orders in the discovery and settlement of the New World: "Before entrusting the discovery to others, put it under the care of those friars who would wish to do it and give them all facilities and security at our cost."

Once the missionaries or civilians were in charge of the discoveries and settlements, several ordinances came into play. Among the more important were the following:

Ordinance Number 29: "The discoveries should not be called conquests, for they have to be made in peace and charity."

Ordinance Number 30: "The discoverers should keep these ordinances, especially those that are favorable to the Indians."

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966