The Children Asked For Bread

Chapter 07

Padre Kino and the Trail to the Pacific Online

|100|

Chapter 7 The Children Asked For Bread 1695

Once again the skies were blue above Dolores. Free from threats of fire and death, in the heat of a September afternoon everyone slumbered, or nodded over his work. Everyone, that is, except Padre Kino.

"What is he doing?" whispered Marcos, son of the new captain general of Dolores, squatting on his heels in the shade of the patio wall.

The fat cook yawned. "He writes a book."

Marcos stared at her. Books he knew. There was the big book in the church. When he served the Mass he carried it from one side of the altar to the other. And there was a small black book that the padre carried with him and read every day, even on their longest journeys. There were books on the table in the padre's room. But write a book? How could you do that?

He looked at the cook, drowsing over the big basket |101| of cucumbers she had brought in from the garden. No use asking her anything. He would go to his father.

The captain general nodded wisely at the question. Yes, Padre Kino was writing a book. It was like writing a message, except it took longer. "You have waited while the padre wrote to someone," said the official.

"You saw how he used the pen."

The boy grinned. "Si, Señor—and got a box on the ears for asking too many questions."

"The padre is angry only when you show disrespect for holy things," reproved his father. "And you must not bother him now, because he writes all about the young Saeta and how he died. And there will be much about Dolores, too, and the other missions, and about all of us. The padre told me."

"Well," said Marcos, "I wish he would hurry. As soon as he has finished writing, he is going to take me to the capital. That is what the padre told me."

Marcos had no idea what the capital was, nor of the fifteen hundred miles that lay between it and Dolores. Throughout September, October and half of November his impatience grew, but still Padre Kino spent long hours in his room, his pen scratching, scratching. The book was for the provincial, the viceroy. Perhaps it would go to Rome. He must not forget anything. |102|

In 1694, when Kino had returned from the trip with Manje, during which they had gazed across at California from the mountain peak west of Caborca, the padre had asked that he be allowed to come to Mexico City for a conference with the provincial. The permission was granted, but when news got around that he was leaving, a torrent of protests poured in to the provincial from soldiers, officials, private citizens and missionaries in the land of the Pimas. Kino could not be spared. He must stay where he was.

Now there was peace, however, and the Pimas, as grateful for the treaty as Kino himself, had begun to restore the mission properties. Fortunately, adobe did not burn, so when the debris was cleared away, all they had to build were new roofs. They had been promised that the padres would come to them once again as soon as the villages were ready for them. And the lean months which followed the destruction of the crops along the Altar River made life under the protection of the padres seem more attractive than ever.

The murderers of Padre Saeta were still unpunished, but they could be taken care of later. They would cause no more trouble. It was quite safe for Padre Kino to leave his charges for a while. And he had even more reasons than before to go to the capital. The ex-captain |103| Solís, trying to excuse himself for his brutalities against the Pimas, had told many lies about them and made personal accusations against Kino himself. There was only one way to deal with such accusations and that was in person.

As soon as the book was finished, Kino put Padre Campos in charge at Dolores and headed south. Right behind him rode Marcos and in the pack train were several other Pima boys, the best-looking, most intelligent ones at Dolores. Padre Kino was not only going to brag about his Indians, he was going to show some of them to the skeptics.

The train proceeded at a steady "Kino-pace" which covered about thirty miles a day. Each morning the padre said Mass. On Christmas Day they were in Guadalajara, only four hundred miles from Mexico City. The wide-eyed Marcos watched with the others while Kino said the three masses of the Feast of the Nativity in a new church named for Our Lady of Loreto. Then they were off again, to arrive in the capital on January 8,1696.

Marcos recognized the hawk-nosed man who greeted them. It was Padre Salvatierra, who had come to Dolores on Christmas Eve, six years before, and traveled with Padre Kino into Arizona. Marcos had been a very |104| small boy then, but no one could forget the kindly Salvatierra. He and Kino appeared together often in the capital and Marcos, trotting behind them, heard over and over again the word California, as the two padres urged the provincial and the viceroy to re-establish the missions there.

Kino had other requests. His memory was long. At the court of the viceroy he told the story of the wicked soldier who destroyed an Indian town when Kino first went to Dolores. The soldier escaped punishment, said Kino, and the Indians were not permitted to return to their lands. He realized that nothing could be done about the soldier who had apparently left the country, but pleaded that the Indians be given their town again, and beamed in happy gratitude when the viceroy granted his plea.

The petition for California was not so successful. Although everyone agreed that the missions should be reopened, money was still not available for the venture.

When it came to the lies told by Solís about the Pimas, Padre Kino said flatly that such arrogant officers as Solís were responsible for the recent Indian uprisings!

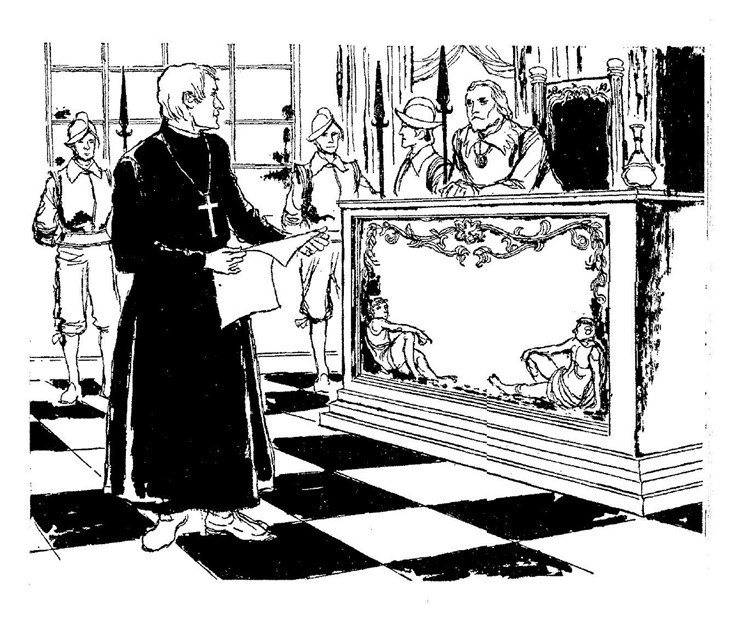

"Look at these Pima boys!" cried Kino, indicating Marcos and his neatly dressed, quiet and polite companions. |105||picture: At the court of the Viceroy in Mexico City, Padre Kino pleaded for the Indians| |106| "The children of Tubutama and Caborca are no different from them. And there are thousands like them in Pima land."

There were tears in Kino's eyes as he pleaded for the children. No one would ever forget him standing there in his shabby black robe, stocky figure shrunken by the months of fever, but feet firmly planted, head thrown back, his eloquence carrying them from the brilliant Spanish court to the humble villages from which these children came.

Even more eloquent than Kino's speeches was the book which he presented to the provincial. The first part of it, about Saeta's murder and the events which followed, was about what the provincial had already been told, for the news had spread through Mexico with incredible speed. But the rest of the book, and the greater part of it, was about the riches of Pima land. The provincial read with growing amazement, for it sounded like Paradise, and the Pimas almost like angels!

Kino had listed the missions one by one—Dolores, San Ignacio and Imuris, Magdalena, Caborca and, last of all, Cocóspora, high on a hill above the river, about thirty miles north of Dolores. Untouched by the rebellion, the mission had extensive lands with forests, |107| fertile fields and orchards, a house and a little church. Most important of all, Cocóspora was on the road to the north in Arizona, where hundreds of natives in large towns were begging for missionaries to come and live among them. They had built houses for the padres, were growing fields of wheat and corn for the Church. The Father Visitor and other padres, and a number of civil authorities had promised them priests, but no priests had gone to them.

Then, Kino's book came back to his martyred friend, Padre Saeta, blaming his death on the resentment which the Indians felt because they needed the fathers, and the fathers did not come.

"The children asked for bread," wrote Padre Kino, "and there was no one to break it unto them."

It was a powerful argument and it was accompanied by a large and detailed historical map of Jesuit New Spain. There were few map makers in the New World. This map alone would cause a sensation.

The provincial made his decision. Five new missionaries would go to the Pimas. Padre Kino could scarcely wait to get home with the news. On February 8 he headed north. He stopped at one of the missions for Holy Week. Where the road turned east, toward Bázerac, Kino turned into it. He must go there to see |108| Padre Polici, who had been appointed Father Visitor of the region for the next three years.

But he sent the rest of his party on to the Dolores with messages to the Pima chiefs. He wanted to see them. June would be a good time. And he bid them all to come. He had good news for them.

The trip to Bázerac took more time than he had counted on. There were several conferences with Polici. And when he wanted to ride on, the Apache sympathizers in that region were on a rampage and Kino had to wait for an army escort. One might wonder who was taking care of whom, because when he left his escort briefly to visit two Jesuit friends, the captain of the troop, his son, and all his men were killed by the Indians. Padre Kino went on safely, and alone.

It was mid-May when he reached Dolores. Padre Campos had not been happy there. He had almost decided to ask for a transfer, to leave Pima country forever, but Kino was so enthusiastic about plans for the future, Campos finally agreed to go back to San Ignacio.

By mid-June the wheat was golden, ready for the harvest, and the chiefs Kino had summoned assembled at Dolores. Padre Kino spoke to them in their own language. He told them how glad he was to be home again. |109| He gave them greetings from the viceroy, the new provincial, the new Father Visitor. They listened gravely, with appreciation. Such greetings befitted their dignity as chiefs. They thanked the padre for bringing them. After the meeting some of the visiting Indians were questioned and those who had had sufficient instruction in the Faith were baptized. Others were told they must wait. They must learn more about God.

Then everybody pitched in to help with the wheat. They cut it with hand sickles and some of them were very skillful. For that matter, most of them had helped Padre Kino with other harvests. It was an honor to help their padre. And besides, when they helped him they helped themselves as well. Every grain of that wheat would go to feed the Pimas, or be traded at the Spanish settlements for clothing to keep the Pimas warm.

When they had gone to their own villages, Kino made a formal report of the assembly, listed the Indians who had taken part, and sent it to the capital of Mexico. If the provincial needed any further evidence of Pima loyalty, this should furnish it. These were the children who asked for bread. Let more priests come speedily to give it to them!