Twin Churches with Domes, Transepts and Turrets

Hall Churches With Flat Roofs

Town Planning and Boat Building

Kino - Builder and Architect

Kino's Pimería Alta Missions

"Kino: A Legacy ..." Map

Kino - Builder and Architect

Twin Domed Churches with Transepts and Defensive Turrets

Mission Nuestra Señora del Santa María de Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera

Only Kino Church Standing With Kino's Walls and Other Building Components

Photographer Robert H. Jackson

Perkin's Notes on

Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera

Arthur Woodward - Chapter 4

In these excerpts from Kino's memoirs, Woodward gives us the key to understanding the Padre's high regard for basic architectural elements and their impact on the natives: he [Kino] speaks like a designer about high and strong walls, good and pleasing arches, and the two chapels which form the transepts, supporting a high cupola [dome] with a slightly lantern above. Among the neighboring Indian tribes the word about such a "heavenly space" at Cocóspera spread to other areas; no wonder the Indians from far and wide (even Yumans) came with gifts to attend the dedication ceremonies!

Buford Pickens, FAIA

Editor's Notes

"The Missions of Northern Sonora: A 1935 Field Documentation" 1993

Cocospera Mission Site - 1864

Engraving from Drawing by J. Ross Browne (Figure 28)

Woodward's Chapter 4: Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera

The mission site is on the crest of an old river terrace which slopes rather abruptly to the stream bed and at this point broadens out into a side valley; the current now flows against the far eastern side of the valley. Here in the fertile flats modern Mexican ranchers have their fields, and with very little imagination or exaggeration one may easily envision the landscape as it was when the mission was in its prime: with herds of cattle and sheep browsing in the pasture lands; with fields of corn, wheat, melons, squash, etc., growing luxuriantly in the rich loam of the flood plains; with the river marked by heavy verdant growth of cottonwood and willow.

Cocóspera, like the famed Topsy of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" - "just grew"! The date of the actual foundation of the church seems a bit hazy? [2] Kino was there in 1689, later in 1691, and probably many other times not mentioned.

In April 1697 Father Ruiz de Contreras became a resident priest. At that time, according to Kino (1919, 1: 166), the mission was equipped "with complete vestments or supplies for saying mass, good beginnings of a church and a house, partly furnished, five-hundred head of cattle, almost as many sheep and goats, two droves of mares, a drove of horses, oxen, crops, etc."

In March 1701 Kino went from Dolores to Cocóspera " ... to cast a glance at my other two pueblos of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios and Cocóspera, because they were frontiers to the enemy, and to provide for their defense by means of some towers ... " (Kino 1919, I: 274). |43|

The master director of all these mission outposts was at Cocóspera again in April 1701, on his return south after visiting San Xavier del Bac. A church and house were being built in Cocóspera at this time by Kino's orders, and he paused here two days to supervise and direct the work. (Kino 1919, I: 292-93, n. 404).

During 1703 work on a large church building at Cocóspera was continued "zealously" in February, March, April, and part of May with the expectation of being able to have it finished and dedicated before the end the year. The work was done mainly by Pima Indians imported from the neighborhood of San Xavier del Bac. The essential details of this construction are best told by Kino himself: [3]

In these months and the following, I ordered the necessary wood cut for the pine framework, sills, flooring, ect. I went to the interior and brought more than seven hundred dollars' worth of clothing, tools, and heavy ware and from other places I obtained more than three thousand dollars' worth, which shortly and with ease were paid for with the goods, provisions, and cattle of the three rich districts. I invited some men [Indians] from the frontier for the work on these buildings, and there came far and away more than I had asked for; and very especially, for entire months, the many inhabitants of the great new pueblo of San Francisco Xavier del Bac, which is sixty leagues distant to the north, worked and built on the three pueblos of this place and of my administration.

In this way many adobes were made in the two pueblos of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios and Santiago de Cocóspera; and high and strong walls were made for two large and good churches, with [44] their two spacious chapels, which form transepts, with good and pleasing arches. The timbers were brought from the neighboring mountains and pineries, and the two good buildings were roofed, and provided with cupolas, small lanterns, ect. I managed almost all the year to go nearly every week through the three pueblos, looking after both spiritual and temporal things, and the rebuilding of the two above-mentioned new churches (Kino 1919, I: 379).

The laborers on the church at Cocóspera were paid in corn, wheat, cattle, clothing, cloth of various sorts, blankets, ect., "which are the currency that best serves in these new lands for the laborers, master carpenters, constables, military commanders, captains, and fiscals" (Kino 1919, I: 378).

In another place Kino refers to the wood used, saying, "The timbers for the frames and flooring, which are very good and almost all of pine called royal, were cut and brought from the neighboring hills, at a distance of seven or eight leagues" (Kino 1919, 2: 80).

A few additional [architectural] data concerning Cocóspera are included in Kino's relation:

Of The Month Of January, 1704,

In Which Occurred The Solemn Dedication

Of Two New And Capacious Churches

The churches of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios and Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera, as all who have seen them say, are among the best in all the provinces of Sonora, Sinaloa, Hiaqui and Chinipas. They both have transepts, formed by two good chapels, with their arches. One of the two chapels of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios is dedicated to our father San Ygnacio and the other to the glorious Apostle of the Indies, San Francisco Xavier; and of the two chapels of Cocóspera one is dedicated to Nuestra Señora de Loreto, and the other to San Francisco Xavier. "Each church has on the arches of the two chapels - which form the transept - a high cupola, and each cupola has in the middle and above a slightly lantern." [emphasis within parenthesis added] (Kino 1919, 2: 86).

The new year of 1704 was ushered in by cold, raw winds and a chilly weather; sickness prevailed. Yet in spite of all this a large concourse of Spanish "gente de razon", visiting priests, and a host of natives from all parts of the Pimería Alta were at Cocóspera on 18, 19, and 20 January to participate in the dedication of the new church. Here were Yuma Indians from the far away Colorado River bearing gifts of the famous blue shells |45| which led Kino to argue for a passage by land to California. [4] Here also were, "people from the nations of the Quiquimas, Cutganes, and Coanopas [Cocopas], ect., nations on the land route to California" (Kino 1919, 2: 7).

The dedication ceremonies "were performed by Father Rector Adamo Gilg, and other fathers, with all the ceremonies and benedictions which our Holy Mother Church commands, according to the holy Roman ritual." The choir from Remedios aided Father Gilg in the singing of the two principal masses. The dedication sermon was preached in Pima by Gilg (Kino 1919, 2: 86-87).

Such are the actual records by Kino of the building of a church Cocóspera.

In July 1730 a Jesuit priest published an account, "Estado de la Province Sonora" (Documentos 1853-57, 617-37). He mentions the church Cocóspera as being in a ruined state.

On 25 February 1698 the Apaches, Sumas, Janos, and Hojomes attack Cocóspera, "at a time when the pueblo was without men, for they had gone inland to barter maize; and although one of the enemy was left dead, they killed two Indian women, sacked the pueblo, burned it, the church, and also the house of the father, who was defended by the few natives had remained. The enemy carried off some horses and all the small stock and retired to the hills. A few from Cocóspera followed him, but when he saw them coming he ambushed them and killed nine of them" (Kino 1919, I: 176). In this instance, Kino seems a bit inconsistent in his description of the attack. He states that "the pueblo was without men," then mentions the defense of the house of the father by "the few natives who had remained," and finally of the pursuit by a "few from Cocóspera" of whom nine were slain.

Apparently, at that time some sort of a church structure had been built at Cocóspera, However, on the afternoon of 22 April 1700 Kino again visited Cocóspera, "where we were received by one hundred and fifty natives who had just returned to settle this pueblo, and had just rebuilt and roofed a hall and a lodge for the father's house, with orders soon to roof the little church also, for three years before on 25 February 1697 (this should read 1698), the hostile Hojomes and Janos had sacked and burned this pueblo ... " (Kino 1919, I: 232-33; and for Bolton's correction

various dates, ibid., I: 176, n. 211). …. |46|

Arthur Woodward

Chapter 4: Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera

"The Missions of Northern Sonora: A 1935 Field Documentation" 1993

Buford Pickens, FAIA, Editor

To download entire book on JSTOR, click →

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2fcct1f

Mission Cocóspera Ruins - 1920

Photographer Frank Pinkley (Figure 30)

Front Facade Added After Kino's Death

Cocospera Mission Plan by William W. Wasley 1965

Kino's Defensive Turrets Marked As Franciscan Towers (Figure 15a)

Cocospera Church Footprint

Length 23 meters (75 ft.); Width 10.6 meters (34 ft.) Height 7.6 meters (25 ft.)

Mission of Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Santiago de Cocóspera

Domes, Transepts and Defensive Turrets

Jorge Olvera

|110| ... Kino was building his churches according to the lower Andalusian mudéjar plan. This means that the naves of Remedios and Cocóspera were going to be covered with a flat, terrado, roof, supported by vigas or wooden beams and corbels (zapatas) with planks perpendicular to the beams (tablazón). In a few words, this is a perfect description of the mudéjar mode of roof building.

We are sure that Cocóspera had been originally covered with a flat alfarje roof over the nave until it was rebuilt by the Franciscans, because Fray Juan de Santiestéban, the Franciscan who rebuilt Cocóspera in the late 18th century, said that before his work, "The church was covered with a flat earthen roof [ ‘el techo de la iglesia era de terrado’], with a corresponding pitch which was not enough, indeed, to prevent leaking due to the badly joined timber planks" (Wasley 1976: 19). We can now speculate that all these flaws can be attributed to the many episodes of abandonment and reoccupation of the mission during a period of raiding and warfare by Apaches. This probably explains why Fr. Santiestéban built a pitched roof over his church.

We think that Father Kino's church at Cocóspera was essentially the same structure that Fray Juan de Santiestéban found in the 1780s before he started to rebuild the often‑attacked mission. What Santiestéban did was simply build his church on the inside and outside of the original structure. He added a veneer of new adobe and burnt brick to the exterior and interior of the side walls and built a new freestanding facade that abuts the original. He did this in the new neoclassic‑style which by the end of the 18th century had already arrived in New Spain (Toussaint 1967: 401‑403). But Santiestéban covered the sanctuary (following the mudéjar mode of lower Andalucía) with a burnt brick barrel, the vestiges of which can still be seen.

|112| Aurthur Woodward, the archeological consultant to the United States National Park Service Sonora Expedition of 1935, .... says “The roof was probably flat, save the chapels which were no doubt vaulted or domed. The walls were adobe and 42 in. thick in the front and rear and 53 in. thick on the sides and approximately 25 feet high.

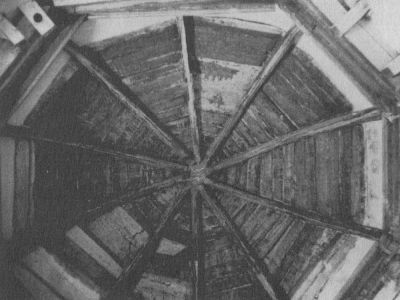

|114| If Father Kino did build his vaults and domes with adobe, they could have been raised using Islamic methods, either with centering or, as is still done in Egypt and describe by Fathy without centering. But Father Kino could also have built them with timber, using the |115| carpinteria de los blanco or mudéjar carpentry system in a way similar to that used for the construction of the domed wooden ceiling of a side chapel of Mission San Miguel de Arcangel de Moctezuma built in the 1720s or '30s in the Moctezuma River Valley of Sonora. The ceiling of this chapel is built as a hemispherical timber truss (Figs. 17, 18). It has a circular structure, or “media naranja,” that springs from a polygonal plan that becomes hemispherical and is made up of sections that adopt a spherical form. [2]

It is reasonable to think that Father Kino could have used this system for the building of his domes. For two years he was in Sevilla, Spain, an area of great Islamic influence and of multiple building methods. Besides this, he frequently mentions trips to the mountain pineries of the Pimeria Alta to get wood for construction. At that time, there seems to have been sufficient timber for the building of his missions. .... At Moctezuma, where the church was built within one or two decades after Kino's death, we see the wooden dome of the side chapel capped by a small lantern.

|116| At this point, I want to stress the missionaries such as Kino, Santiestéban at Cocóspera, and Juan Martínez and the second Manuel González were no make-shift builders, as has sometimes been erroneously thought, but were very well versed in architecture and building methods.

|123| The following notes are brief descriptions, made by Kino himself, of the missions he had been building in the Pimeria Alta at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th. Most come directly from Father Kino's diary, Favores Celestiales. . . . The original Spanish version of the diary is the best.

Kino (1913‑1922: Chapter VII: 184‑185): The construction of the churches of Remedios and Cocóspera (1702). Cocóspera was the third pueblo in the administration of Father Kino. Father Kino used pine for the ceiling beams and lathes at Cocóspera. The church seems to have had a ceiling of vigas (beams) supported by corbels (alfarje is the Spanish word of Arabic origin for this type of roofing system). Kino describes it: ". . . mande cortar las maderas necesarias para la viguería de pino, zapatería, tablazón, etc." (". . . I ordered the different and |124| necessary wood cut such as that for the pine beams, for the corbels, planks, etc.") [my translation] .[5]

. . many adobes were made in the two pueblos of Nuestra Senora de los Remedios and Santiago de Cocóspera; and high and strong walls were made for two large and good churches, with their two spacious chapels which form transepts, with good and pleasing arches. Timbers were brought from the neighboring mountains and pineries and the two good structures were roofed with their corresponding domes and lanterns, etc." [my translation].

In my notes I have the following personal observations made on site and based on my reading: Kino built—although in adobe—churches provided with domes and lanterns, as he writes of domes and lanterns raised over the transepts. But at Cocóspera, all traces of the original Kino dome and lantern have unfortunately disappeared. Only a very shallow kind of transept can be deduced by measuring and tracing the original Jesuit ground plan, as Dr. Wasley and I did (see Fig. 15). A very interesting vault still exists over the sanctuary, but I believe it is a Franciscan structure because it is built of fired brick, a material introduced by the Franciscans after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767.

In a last effort to understand how Father Kino might have built the missions of Remedios and Cocóspera and roofed them with domes and lanterns, I am strongly inclined to believe he resorted to mudéjar timber carpentry techniques and that he built the domes, like the one still extant at Moctezuma, entirely of wood.

There are good reasons for believing this. The first is based on semantics of the Spanish language and a second is based on his own writings.

|125| Again, whenever Kino writes about the mission churches, he is building, he always mentions the “cuasinques,” or carpenters. Reading between the lines, I can detect two well defined stages or steps in his building methods.

The first was the mud brick masonry stage, with a): the building of the foundations with locally gathered stone materials (river boulders or, if available, volcanic rock as at Franciscan built San Xavier del Bac), as he tells us in another part of his diary, and b): the raising of the adobe walls for his buildings, workers having previously gone through the long process of making the adobes, whose clay had to be dug, mixed with water and binding materials, set, removed from the molds, and dried.

The second stage in the building process was the one in which he employed the carpenters who travelled with him. They arrived at mission sites where local people had already made adobes and had raised the walls to a convenient height for roofing. At this point, now under the supervision of Father Kino, the carpenters would start to roof the structure over the nave, sanctuary, sacristy, etc.

|126| We can see this sequence perfectly in Kino’s description of the building of Remedios and Cocóspera” He indicates three logical steps in the construction of those mission-churches when he says:

1) ". . . many adobes were made in the two pueblos of Nuestra Senora de los Remedios and Santiago de Cocóspera; and high and strong walls were made for two large and good churches, with their two spacious chapels which form transepts, with good and pleasing arches. . . ."

2) "Timbers were brought from the neighboring mountains and pineries. . . ."

3) ". . . and the two good structures were roofed with their domes and lanterns, etc."

He doesn't speak of a mixed or combined building system for roofing; that is, if part were to be flat (nave, arms of the transept, etc.) and part domed (such as the sanctuary or the crossing). If he were building his domes with adobes, he would have mentioned the words “cimbra” or “cercha”: "centering."

|135| The following notes ... include a very interesting piece of information from Father Kino's original diary (1913‑1922: IV: 121) one which says, "I went to take a look at my other two pueblos of Nuestra Senora de los Remedios and Cocóspera and, because they were on the enemy frontier, to provide for their defense by means of some turrets. . . ."

Those who have not read Father Kino's original diary in Spanish, but have instead followed Bolton's translation (Kino 1919) and looked for remains of "towers" at Cocóspera and Remedios are unlikely ever to find them. This is because Kino doesn't say he went to those two pueblos to provide for their defense by means of towers, but by means of turrets. Turrets are small towers, usually circular in section and cylindrical in elevation, and which generally form part of a larger structure. [1]

|136| At Cocóspera, Kino already had a large tower located on the gospel side of the nave and flush with the facade, which according to Dr. Wasley, could have served for defense. Besides this bell tower, he could have later built the two turrets (not towers) inside his own nave since the bell tower, because of its large opening, is not well suited for defense and leave the building vulnerable to attack.

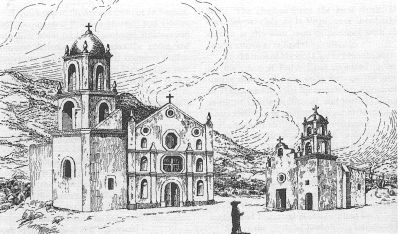

|

|137| J. Ross Browne’s representations are the most complete because they were done earlier when the monument seems to have been more or less intact, at least in the Franciscan reconstruction. The bell tower presumably built by Father Kino is missing from the picture. (Fig. 28)

|138| This is the best depiction for several reasons. It shows the complete and very well‑proportioned mission church with some detail in spite of its being a view from a distance. It also makes clear the strategic setting of the mission on a bluff, one of the outstanding characteristics of Kino missions and a piece of information that later became very useful in helping us locate Kino's chapel of Saint Francis Xavier.

The turrets are also very well drawn, but neither in this picture nor in the other by Browne do the loopholes appear. We know that these turrets, built for defense, could not be blind. Their very purpose was to have them pierced by loopholes. Besides, a photograph taken in 1920 by Frank Pinkley still shows the remains of two loopholes, one on each of the two ruined turrets (see Fig. 30). [See photo above]

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

Timber Truss Dome of Mission San Miguel Archangel de Moctezuma

Photographer Charles Di Peso (Figure 18)

O'odham Church Builders

Remedios and Cocóspera In New Array

Herbert E. Bolton

The particular ministry to which he now devoted himself was the completion of the churches at Remedios and Cocóspora. What with Kino's many occupations and the Apache attacks, building had gone slowly at these places, though he had under way two fine churches, each with a transept, which was not common in Sonora. It is interesting to follow their varied fortunes, for they illuminate the daily life of the great missionary. When he went north in February, 1699, Kino left the walls of the church at Remedios "nine varas high and ready to be roofed." In his absence there were heavy rains, and on his return he found that the edifice had suffered greatly. "The conduits were now clogged and the water, collecting in a great pond, soaked the foundations so that the presbytery fell down, which it was a great pity to see." When he saw the havoc his heart sank, but he set about repairing the damage.

A year later the work was still in progress and Manje noted that the temple when finished would have "the best nave and transept of all those in the province of New Spain." [2]

Building operations at Cocóspora were even slower than at Remedios, for they suffered a still greater disaster. When in March, 1697, Kino turned Cocóspora over to Father Ruíz, there were "complete vestments or ornaments for saying Mass, good beginnings of a church and a house, partly furnished, five hundred head of cattle, almost as many sheep and goats, two droves of mares, a drove of horses, oxen, crops, etc." Kino had been active there.

Ruíz remained at Cocóspora only a year, when he was driven out by an Indian attack. On February 25, 1698, the Jocomes, Sumas, and |520| Apaches swooped down on the place at a time when most of the men were away. Ruíz and a handful of defenders put up a good but a losing fight. The enemy killed a number of neophytes, sacked the pueblo, and burned it. When they pursued the marauders, the defenders were ambushed and nine of their number killed. Father Ruíz, having lost everything, even to his clothes, fled to the interior. The natives, too, deserted, and for two years Cocóspera was without missionary or inhabitants.

But confidence was gradually restored, and in April, 1700, Kino found at Cocóspera one hundred and fifty natives "who had just returned to settle this pueblo, and had just rebuilt and roofed a hall and a lodge for the father's house, with orders soon to roof the little church also." [1] The rebuilding and the administration of the mission were now in Kino's personal charge. A year later he fortified the pueblo with towers.[2]

After Kino returned from his journey to the Colorado in 1702 he hoped to follow up the triumph by another expedition, one which would take him clear around the head of the Gulf and down the California coast to Loreto. In imagination he saw himself embracing Salvatierra, Picolo, and Ugarte there and telling of his adventure. At the same time, his visits to the industrious Yumas and Quiquimas inspired him with the idea of going to Mexico to appeal for more missionaries, as he had done after the martyrdom of Saeta. The plan to go to the capital seemed timely just now. ...

Now, at the end of 1702, his projected journeys to the Colorado and to Mexico having been prevented, Kino turned as a major interest to the completion of the churches at Remedios and Cocóspera. In a little more than a year they were finished .....

"Because my going to Mexico, as well as to California, had been prevented, I applied myself to building with all possible vigor and speed, so as to have this work more advanced, the two churches in my second and third pueblos, on which small beginnings had been made." He had set himself a standard and now he rose above it. "When the Father Visitor, Antonio Leal, saw this church of . . . Dolores, he said it was one of the best he had seen in all the missions. Nevertheless, the new ones which I undertook in the following months turned out even better, for they have transepts." ...

I have tried to have in the three pueblos of my administration [Dolores, Cocóspera and Remedios] ... sufficient supplies of maize, wheat, cattle, and clothing, or merchandise, such as cloth, sayal, blankets, and other fabrics, which are the currency [form of economic exchange] that best serves in these new lands for the laborers, master carpenters ....."

The neophytes were willing workers, and distant chiefs vied with each other in the number of grandules they could contribute to the enterprise. Sometimes they came with their entire families, and then Cocóspera looked like an Indian camp. .....

"In these and the following months," Kino continues, "I ordered the necessary timber cut for the pine framework, sills, flooring, etc. I went into the interior and brought more than seven hundred dollars worth of clothing, tools, and heavy ware, and from other places I obtained more than three thousand dollars' worth, which shortly and with ease were paid for with the goods, provisions, and cattle of the three rich districts." [1]

To assemble workers, messages were sent far and wide. Bac [Wa:k] especially responded. "I invited some men from the frontier for the work on these buildings, and they came far and away more than I had asked for; and very especially, for the entire months, the many inhabitants of the great new pueblo of San Francisco Xavier del Bac, which is sixty leagues distant to the north, worked and built on the three pueblos of this place and of my administration."

Captain Coro came with his men. Other chiefs and their subject rallied "from the west, the southwest and the north with their whole families." Thousands of adobes were made "and high and strong walls were erected for two large and good churches, with their two spacious chapels, which form transepts, with good and pleasing arches. The timbers were brought from the pineries of the neighboring mountains, and the two good buildings were roofed, and provided with cupolas, small lanterns, etc."

All this work Kino personally superintended, continually riding back and forth from one mission to another. He tells us, "I managed almost all the year to go nearly every week through the three pueblos, looking after both spiritual and temporal things, and the rebuilding of the two above-mentioned new churches." The round trip was nearly a hundred miles ....

Remedios and Cocóspera ... "would have cost ten thousand pesos were it not for the fact that, thank the Lord and His celestial favors, through the fertility of the land of these new conversions, .... the expenditures were reduced to five hundred beeves for consumption during the construction of these two buildings, five hundred fanegas of maize, and about three thousand pesos in clothing, which is the money [paid to and] used and current among the native of these new conversions."

At last the two beautiful churches were finished. The dedication was a great event for all the Pimería. .... Indian friends responded from far and wide. "Many natives from the interior, from the north, west, and especially the northwest, attended the two dedications, greatly to our pleasure. Many of them came more than one hundred leagues, as did the captain of the Yumas, with many of his people." They had trudged three hundred and fifty miles .....

Now, in the dedications, Kino found encouragement for his California dream. The Indians from the Colorado did not come empty-handed, but brought what they knew Father Eusebio most prized. They came with "gifts of shells from the head of the Sea of California, and with very good messages from the ... Quiquimas, Cutganes, Coanopas, etc., nations on the land route to California."

Herbert E. Bolton

Remedios and Cocóspera In New Array

Chapter 135

New Ranches and Temples Section

Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer

Chapel in Tohono O'odham Village

O'odham Church Building Tradition Beginning With Kino

Editor Note: The O'odham People were attracted to the charismatic Kino and would travel year round to Kino's Mission Dolores headquarters to help him plant and harvest crops, herd sheep and roundup cattle and receive in return food and clothing in payment and as gifts.

However very few Spanish colonial historians acknowledge how the O'odham people throughout all of the Pimeria Alta would travel from their homes to help Kino build his churches at Dolores and the two great churches that were completed in late 1703 after one year of construction. Herbert Bolton uses excerpts from Kino's "Favores Celestiales" to give an account about the workers and their families. The editor believes that the tradition building Kino's churches continued with the building of Mission San Xavier del Bac and the chapels built in many Tohono O'odham villages. Internationally renowned folklorist and anthropologist James "Big Jim" Griffith states that the tradition of building village chapels began in the late 19th century and was inspired by the mission churches in Sonora.

Remedios Mission Site - September 2024

Remedios Church Footprint

Length 30 meters (98.4 ft.); Width 10 meters (32.8 ft.) Height 7.6 meters (25 ft.)

Courtyard Enclosed By Buildings

Length 50 meters (164 ft.); Width 25 meters (82 ft.)

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Remedios de Doágibubig

Domes, Transepts and Turrets

Remedios "an example of fine art and architecture ... largest In Sonora"

Juan Matheo Manje

April 16, 1701

Here we found the Father’s residence already finished and beautifully painted. Much progress had been made on the walls and main part of the church – an example of fine art and architecture, which when finished, will be the largest in Sonora – it culminates in three semicircular vaults supported by cornices and exquisite capitals.

Juan Matheo Manje

April 16, 1701

Remedios Site Plan

William W. Wasley - 1966

Church structure is vertical rectangular figure identified as the nave (left).

Larger horizontal rectangular figure is the enclosed plaza with other buildings (right).

Remedios Mission Plan - 1965

Jorge Olvera

Mission Church (vertical rectangular figure in left one-third of drawing)

Length: 30 meters (90 feet); Width:10 meters (30 feet): Walls: 25 Feet

Enclosed Plaza With Other Buildings (horizontal rectangular figures with X)

50 meters (150 feet) by 25 meters (82 feet)

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Remedios de Doágibubig

Kino Architectural Archeology

Jorge Olvera

|217| Remedios is located on a mesa, and the ruins of Father Kino's mission border a relatively deep canyon on the edge of which the apse and sanctuary of the church is built. ....

The site is located on the west side of the Rio San Miguel. The ruins of the church consist of melted walls that have turned into mounds, |218| but they still outline the general form of the nave, one invaded by a modern cemetery. Through the study of these ruins, I was able to see that Father Kino had built his church on the highest part of the mesa and that it was oriented north‑south. The main facade and entrance were to the south, and what seemed to be the lateral entrance was oriented towards the east. Towards the same cardinal point was an enormous walled‑in space which most probably comprised the casa cural, or rectory, and the mission compound. ...

I was able to confirm that the length of the nave, from facade to the apse, measured 30 meters, exactly the same length as that of the present church of Magdalena. And when I measured the width of the facade, I saw something I could hardly believe: the total with of the facade was 10 meters, exactly the same as that of the facade of the Magdalena parish church. This, of course, discounts the widths of the flanking bell tower and sacristy of Santa Maria Magdalena. ...

Continuing my checking of Dr. Wasley's measurements near the facade on the west side of the nave, I measured a somewhat square mound that may have been the remains of an abutted structure, possibly a baptistery. Also taking into account the melting down of the adobe structure, it could originally have been approximately 2 or 2.50 meters by 4 meters. On the same side, but near the apse, there was a similar mound, much more eroded, but the same size as the former one |219| (2 or 2.50 m. by 4 m.). Finally, on the east wall, there was a third rectangular mound approximately the same size as the first two.

|219| On the east side of the church, there was a huge patio, one that most likely had been enclosed by a wall (see Figs. 67, 68). In spite of the melt down of the adobe structure, the contour lines of the walls could still be seen. That is why Dr. Wasley included them in his sketched ground plan. The living quarters and workshops doubtless were within this enclosure. We were able to detect a series of buildings on the extreme east end of this enormous patio that measured 50 m. by 25 m.

In addition to the fact that the mission had been built on a high mesa bordering a deep ravine, with the apse of the church on its very edge, the entire plan of the mission was that of a fortress. There was only one entrance to the whole mission compound, the door of the main portal. The only entrance to the huge patio was through the door of the side portal that led into it.

Even from what little remained of the ruins, we could see that Remedios was very well fortified. We also know that in order to defend the place from Indian attack, on March 1, 1701, Father Kino had turrets built for added protection, both here at Remedios and at Cocóspera (Kino 1919: I: 274).

My first impression was that the most vulnerable parts of the mission where the turrets could have been built were the southern and extreme eastern parts (see Figs. 68, 69). |220| the remains of two of three huge circular buttresses located on the north side of the mission correspond to the turrets that Father Kino mentions in his diary. The one I measured (see Fig. 70, located on the northeast corner of the apse) seems more to correspond with a circular or conical buttress (guardacanton). .... They served instead as buttresses to help prevent the apse from collapsing into the nearby ravine. ...

The diameter of the circle—corresponding to a circular buttress—that I traced while measuring the northeast corner of the apse of Remedios was almost five meters, very large indeed. It was this that made me think that this circular buttress could originally have been more of a turret than a truncated conical guardacanton. ... |221|

|221| The churches at Remedios and Cocóspera were built at the same time and were apparently nearly identical. Both were cruciform with transepts formed by arched chapels (Roca 1967: 127). We also know that at the end of the 17th century "work continued on the church [at Remedios] during the next several years, with fortifications being added in February, 1701" (Roca 1967: 127).

Juan Matheo Manje, the Spanish soldier who was often Kino's travelling companion, wrote about his visit to Remedios on April 16, 1701: "Here we found the Father's residence already finished and beautifully painted. Much progress had been made on the walls and main part of the church—an example of fine art and architecture, which, when finished, will be the largest in Sonora—it culminates in three semicircular vaults supported by cornices with exquisite capitals" (Burrus 1971: 277).

What Dr. Wasley was able to find during his surveying at the extreme end of the great patio east of the church were no doubt living quarters similar to those described for the village of Cocóspera. That village "was surrounded by a small rampart wall, and within this enclosure all lived with the knowledge that each one should possess and live in their own quarters" (Ocaranza 1933: 163‑166).

The layout was like that of a small 16th century presidio. I have visited ruins of several 16th‑century presidios in north‑central Mexico. There is only a single entrance to the main bastion—which at that time was generally a rectangular structure like the nave at Remedios—provided with loopholes instead of windows. The very dangerous situation of the Remedios mission with respect to its being exposed to regular attacks by nearby Apaches, and the orientation of the nave with the sanctuary to the north and the entrance to the south, makes me suspect this church also had a transverse clerestory window and no windows on the side walls of the nave. Apaches could easily scale walls, and ... that is why Father Kino always stressed the point that he was building churches "with very high walls." |222| ...

While we were at Remedios, Dr. Romano oversaw excavation of the ruined apse. He keenly observed that Father Kino employed a system of building on steep terrain similar to that found in the missionary's native Alpine region of Trent. At Remedios, as he had known from northern Italy, Kino had terraced the declivity of the ravine and built his church on the edge of a cliff for defense. ...

The foundations were made of river boulders bonded with clay‑and‑mud mortar. With the remaining walls, they rose to a height of approximately 3.72 meters. Once this section had been cleared and a part of the footings and walls had been exposed where no erosion had occurred, I was then able to study the composition, grade, and consistency of the adobes and to measure their dimensions. My notes have two measurements for the widths: 0.30 m. and 0.33 m., the latter probably coming from a better preserved sample. They were 0.40 m. long and approximately 0.12 m. thick. Their color was a light gray, and the clay was mixed with a good percentage of small gravel. The flush joints of the mud‑and‑clay mortar were about 4 cm. thick and were of a different color, one bordering on orange. The adobe made nowadays—according to one of the laborers—is quite different. The clay is now mixed with wheat straw.

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

Santa María Magdalena Church, Magdalena, Sonora - built 1834

Present Magdalena Church's Footprint Similar to Remedios Church

Length 90 Feet, Width 30 Feet

Present Madgalena Church's Footprint Similar To Kino's Remedios Church

Jorge Olvera

I was able to confirm that the length of the nave [of Remedios), from facade to the apse, measured 30 meters, exactly the same length as that of the present church of Magdalena. And when I measured the width of the facade, I saw something I could hardly believe: the total with of the facade was 10 meters, exactly the same as that of the facade of the Magdalena parish church. This, of course, discounts the widths of the flanking bell tower and sacristy of Santa Maria Magdalena.

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

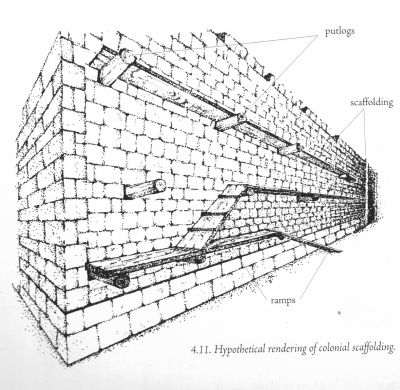

Scaffolding For Building Walls Up To 35 Feet High

Adobe Bricks and Scaffolding For High Walls

Gloria Fraser Giffords

|76| ... Two of the simplest and most available building materials, and mud clay were used extensively throughout northern Spain. They can be poured, puddled, patted, pounded, or molded into bricks or entire sections of wall.

From the Arabic “at-tub” (sun-dried brick), adobe was introduced into Spain by the Moors. It is one of the world's oldest building materials, dating back to around 5,000 BC, when it was used in Crete. To make an adobe brick, a stiff, doughlike mixture of earth (with high clay content), water, and (where available) straw is firmly packed into a rectangular wooden mold. When the mud begins to pull away from its sides, the mold is removed and the block allowed to dry. If the humidity is low enough, the brick is turned on end after a few days to continue drying; after a week, it can be stacked for curing, a process that takes about a month. For ease in handling, bricks are most often made near the building site, provided the soil type is suitable. While sizes vary, they rarely exceed thirty‑five pounds, about the heaviest weigh a worker can handle unassisted. |96|

To build any wall higher than a worker could reach from ground level required some form of scaffolding ("andamio"). One common technique made of putlogs ("almojayas") inserted into the wall at right angles in a horizontal line at intervals of about four feet; these were braced both vertically and horizontally by poles ("almas") or boards lashed together. Ladders or ramps provided access to walkways holding laborers and building materials (figure 4.11). When a building was finished or a section completed, the putlogs were cut off or removed and the holes filled or plastered over, to be reused during repairs in some cases. ... |104| Molded adobe bricks enabled masons to raise higher walls, up to thirty-five feet, and thus span greater spaces, although owing to adobe’s low structural strength, these walls tended to be thick and massive. Churches of impressive size and stability were made from adobe bricks throughout New Spain.

Gloria Fraser Giffords

Sanctuaries of Earth, Stone and Light:

The Churches of Northern New Spain, 1530-1821

Domes of Mission San Xavier del Bac

Symbolism of Domes

Roger G. Kennedy

Transepts and domed crossings were Jesuitical. ...

The grand-slam Baroque cruciform plan was very rarely used in even the largest of mission churches built by Spain within what is now the United States. ...

American domes owe something to Islam, but more to the Council of Trent. The Council summoned Catholic Europe into simultaneous crusades against corruption and Protestantism at a crucial moment. Spain was collecting itself to sustain assaults of Columbus, Cortés, and Coronado and readying itself to colonize what it had conquered, reach out of the valley of Mexico toward the north and the south.

In 1563 the Council called for Counter Reformation. The dome became one index of the movement, even in Mexico, where there was no Reformation to counter. In the hands of the Jesuits the dome was a symbol of the resurgence of the Church Militant, blazoning its confidence in mission churches ...."

They could instruct an Indian work force in making round vaults – a task beyond the skills of the English colonist until after 1795.

The creation of domes is a proclamation of human pride. It assets that humankind may participate in the ordering of the universe. The fame of heroes echoes from the dome of heaven. They may appropriately be interred with a form that makes the point for those who missed it the first time. The earliest Christians saints are martyrs were put to rest in the round, domed building, called martyria, traditional forms borrowed from ancient heroes' tombs and from the sanctuaries of mystery cults.

Tucson is not too distance, architecturally, from Jerusalem; the dome of the Holy Sepulcher is one prototype for the domes of San Xavier del Bac. ...

The sanctuary at San Xavier del Bac has the most complete surviving ornament and fixtures of any mission church in the United States.

Roger G. Kennedy

The Mission: The History and Architecture of The Missions of North America

The Spirit of Kino Shown In His Building of Domes

Jorge Olvera

I am citing these examples of mathematical religious symbolism hoping to deepen our understanding of the spirit of Kino ...

... whenever Kino tells us he is building a mission church provided with a transept and covered by a dome or cupola, as at Cocóspera and Remedios, his intention is not to demonstrate his knowledge of architectural fashion. Rather, he is trying to express his praise to the Creator ...

Father Kino, as we can see by his diary, was a man of great sensibility touched with a messianic drive who and who loved astronomy and mathematics. It is unthinkable he would have missed coming into contract with the mudéjar tradition of Sevilla and its surroundings as represented by El Aljarafe, a famous center of master craftsmen. Evidence of such contact lies in the remains of his ruined missions, churches built on the mudéjar plan of Lower Andalucía, and in his own diary in which he uses some of the mudéjar roof construction terms. Nor could he have missed coming into contact with the religious and musical symbolism implicit in the mudéjar terminology of timber roof construction. The very names of the harmonical proportions of the timber truss structures ....

In the case of the domes he tells us he built at Remedios and Cocóspera on mud brick structures, he would have used the mudéjar sacred and mathematical octagonal plans (as the Franciscans later did for the drum supporting the main cupola of Mission San Xavier del Bac).

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Euesbio Francisco Kino 1965-1966

For Two Years Kino Worked and Learned Mudejar Building in Andalusia

Olvera Map of Andalusia (Figure 06)

Gloria Fraser Giffords

Mudéjar Architectural Tradition

|13|... “Mudéjar” has become a catchall term for a variety of Hispano Moorish features, materials, and techniques, especially in Mexico, where it is used to describe an aesthetic philosophy; decorative treatments of brick, tile, and wood; and certain window or arch shapes. Although the mudejar style dates back to the twelfth century in Spain and arrives in New Spain with the first Spaniards, its vocabulary and respect for the inherent qualities of materials have endured to the present day.

In northern New Spain, we encounter these in rubble filled walls; flat roofed, post and beam construction; ogee and multilinear arches (features shared with Gothic); stepped or pyramidal crenellations; patios with fountains, running water, or ponds; molded or carved ornamental plaster and stucco, including carved pilaster friezes and bands around windows and doors; decorative use of stones pressed into mortar joints and of fired brick forming patterns, profiles, or textures on walls; and glazed polychrome tiles (or painted facsimiles) along walls or embedded in church domes and fountains. We see them also in fluting or goring on arches and domes; in the “alfarje” (elaborate pieced woodwork) appearance of carved and painted beams and corbels; in the “artesonado” (paneled and inlaid) doors, shutters, and furniture; and in the strongly Moorish pavilion and shed roofs over apses and naves of sixteenth century churches in Mexico City—still a distinctive feature of sixteenth and seventeenth century churches in the state of Chiapas and in Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, the province of Andalucia, and North Africa. ...

There is something almost subliminal in Islamic decorative art and architecture—a sensual and refined sense of beauty, an acknowledgment and respect for material, and, especially, a geometric order inspired by the metaphysical and cosmological symbolism of the circle and square. Here, based on mathematical forms, shapes are combined to reflect celestial archetypes within the mind and soul as well as the cosmos. Islamic art and architecture would powerfully influence the Renaissance concept of anthropometry, in which the proportional ideals for painting, sculpture, and architecture were to express the physical perfection of the human form.

To travel across northern New Spain is to witness the impact that the Moorish architecture of North Africa—via Andalucia—had on the design and construction of this region's churches. We can see this in the distinctive fortified appearance of numerous seventeenth and eighteenth century churches, for example, San Miguel Arcángel in Santa Fe (New Mexico) and San Bonaventura (Chihuahua). The churches of Andalucia, with their crenellations, polygonal apses, buttresses, and small, easily defendable windows, influenced these structures either directly or indirectly through the sixteenth century churches of central New Spain.

Even though the shapes, forms, sizes, and purposes of the early Christian churches differed from native expressions, the need to solve similar, problems of defense, heat, and light using essentially the same materials gave rise to architectural similarities between the dwellings of the Pueblo Indians and the churches and conventos of Nuevo Mexico—and indeed, between these and arid land, sun dried mud structures the world over. If, however, we look at the details of the churches of Nuevo Mexico (and some in Nueva Vizcaya and the Pimería Alta), we can clearly trace their lineage to Andalucia and from there back to the “ksar” structures of North Africa, especially Morocco.

Throughout the arid Islamic world, a vast expanse of many nations and frequently warring factions, structures were fortified in appearance and function to ensure the safety and privacy, of extended families and clans. Lacking quarriable stone, builders used sun dried mud (adobe) to form walls and roofs. They covered the buildings' surfaces with plaster, molded and painted to resist erosion and to give their buildings a finished and aesthetically pleasing look. Lacking large trees for beams or ample wood of any size, they made their rooms narrower; artisans fitted smaller pieces of wood together to form elaborate and complicated ceilings, doors, shutters, and pieces of furniture. To guard against the relentless sun and ever threatening marauders, walls were made thick and windows |14| small and high above the ground, producing cool, easily defendable interiors.

All these features were brought by the Moorish conquers to Andalucia, where they became part of the vernacular of southern Spain; from there, transplanted to New Spain to serve the same ends. Among the extant churches of northern New Spain, the most important structural detail reflecting this lineage is the transverse clerestory, found in virtually every church in Nuevo Mexico ... and in some churches of Nueva Vizcaya and the Pimería Alta, and admirably suited to the fortresslike churches of northern New Spain. In the traditional clerestory, upper stage windows run the length of the nave, typically on both sides. In the transverse clerestory, by contrast, a horizontal window runs across and above the nave either at the beginning of the transept crossing or just before the sacristy, choir, sanctuary, or apse. Just as the carefully aligned windows or wall slots of the mosque direct light onto the North African Muslim's focus of devotion - the mihrab - so the transverse clerestory, placed carefully above the nave, directed light onto the sacred focus of the Christian church - the main altar, located at the rear wall of the apse.

Decorative details reflecting the same lineage—the alfarje and artesonado traditions of Andalucia and North Africa—are numerous. ...

Gloria Fraser Giffords

Sanctuaries of Earth, Stone and Light:

The Churches of Northern New Spain, 1530-1821

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Cosari

The Mother of Kino's Missions

Artist Astronomer - Planetary Scientist William K. Hartmann

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Cosari

Herbert E. Bolton

The Mother of Missions

|249| This was March 13, 1687. ... Five leagues up the valley of the San Miguel River they came to the village of Bamotze, or Cosari, home of Chief Coxi.

Coxi was absent when Kino arrived, but his people were assembled and waiting, for Aguilar had notified them the day before; and they gave the visitors an affectionate welcome, "for, months and years before, they had asked for fathers and holy baptism." ...

|252| They ordinarily founded their missions near the villages of the Indians for whom they were designed. And these were usually placed at the most fertile spots along the rich valleys of the streams. The natives were the engineers. And so it was with the village where Kino founded Dolores. Near where Cosari stood the little San Miguel breaks through a narrow canyon whose sheer western walls rise several hundred feet |253| in height. Above and below the canyon the river broadens out into rich vegas of irrigable bottom lands, half a mile or more in width and several miles in length. ... At the canyon where the river breaks through, the western mesa juts out and forms a cliff, approachable only from the west. ...

On this promontory, protected on three sides from attack, and affording a magnificent view, Kino placed the mission of Dolores. Here till recently stood its ruins, in full view of the valley above and below, of the mountain walls on the east and the west, the north and the south, and within the sound of the rushing cataract of the San Miguel as it courses through the gorge. ...

Before the end of April, with the aid of the willing natives, he had built on the commanding hill a chapel for services and a simple house for himself. .. By this time numerous Indians had moved to Dolores from the country round about. The place now presented a busy building scene, where the natives were making "adobes, doors, windows, etc., for a very good house and church" to replace the temporary structure.

|323| [In 1695,] The mission had a fine church, a good and spacious residence, farm buildings and workshops, a pack train, productive fields, flourishing gardens and orchards, and well-stocked ranches. It was in reality a substantial village, a complete frontier unit of mission culture and of agricultural exploitation. ...

"This mission has its church adequately furnished with ornaments, chalices, cups of gold, bells, and choir chapel; likewise a great many large and small cattle, oxen, fields, a garden with various kinds of garden crops, Castilian fruit trees, grapes, peaches, quinces, figs, pomegranates, pears, and clingstones. It has a forge for blacksmiths, a carpenter shop, a pack train, water mill, many kinds of grain, provisions from rich and abundant harvests of wheat and maize, and other things, including horse and mule herds; ...

|324| All these multitudinous activities and establishments were conducted by a well-organized and numerous corps of native officials, functionaries, and craftsmen, trained by the master. Kino continues: “Likewise in this new mission of . . . Dolores, besides the justices, captain, governor, alcaldes, fiscal mayor, alguacil, topil, and other fiscals, there are masters of chapel and school, mayordomos of the house, and other servants whom they call cowboys, muleteers, ox drivers, bakers, rope-makers, gardeners and painters [vaqueros, arrieros, boyeros, panaderos, bolineros, hortelanos, and pintores ]."

|520| "Because my going to Mexico, as well as to California, had been prevented, I applied myself to building with all possible vigor and speed, so as to have this work more advanced, the two churches in my second and third pueblos, on which small beginnings had been made." He had set himself a standard and now he rose above it. "When the Father Visitor, Antonio Leal, saw this church of . . . Dolores, he said it was one of the best he had seen in all the missions. Nevertheless, the new ones which I undertook in the following months turned out even better, for they have transepts." ...

I have tried to have in the three pueblos of my administration [Dolores, Cocóspera and Remedios] ... sufficient supplies of maize, wheat, cattle, and clothing, or merchandise, such as cloth, sayal, blankets, and other fabrics, which are the currency [form of economic exchange] that best serves in these new lands for the laborers, master carpenters ....."

Herbert E. Bolton

Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer

Transverse Clerestory Windows of Glazed Glass

Gloria Fraser Giffords

|91| Founded in 1542 in Puebla, by the eighteenth century, New Spain's glass industry produced not only window glass but vessels and decorative pieces deemed superior to any in Spain and comparable to the finest of Venice and France. In the churches of northern New Spain, window glass provided light, especially in domes and along nave walls; it kept out dust, animals, and the elements; and it protected holy objects, paintings, and sculptures in their frames and niches. ... Most notably, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino's mission headquarters of Nuestra Senora de los Dolores de Cosari (Sonora) ... had glazed windows.

Gloria Fraser Giffords

Sanctuaries of Earth, Stone and Light:

The Churches of Northern New Spain, 1530-1821

Casa Cural, Magdalena Church and San Xavier Chapel - Concept Drawing

Jorge Olvera

Santa María de Magdalena and Capilla de San Xavier

Jorge Olvera

Kino Supervising Carpenters

|139| Magdalena, Sonora, September 25, 1965

One of the most important building blocks in our eventually successful search for Father Kino's remains turned out to be Kino's own explanation of helping Father Augustín Campos build the mission church of Santa María Magdalena around March 1706.

We studying all the points dealing with the architecture of Kino's missions because we wanted to be able to recognize the buried remains of the Campos church or of the chapel of Saint Francis Xavier should we come upon them during excavations. There was, we knew, no one better than Father Kino himself to describe his building methods. In 1706 he was very busy building several churches for Father Campos, as he tells in his diary:

"At this same time, in this nearer Pimería, we had in hand the building of the churches of Father Agustin de Campos's pueblo of Santa Maria Magdalena and of San Ambrosio del Busanic, Santa Gertrudis de Saric, San Pedro y San Pablo del Tubutama, San Diego del Pitiquin, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción del Cavorca (and others), and in this mission ... it was attempt to advance the building of all. To this end I took with me the guasinques, or carpenters, now somewhat expert of this pueblo of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores; and so, after my return on March 2, and around the middle of March, I was in Santa María Magdalena supervising the cutting and assembling the timbers for the construction of the arches of the sanctuary of the very good church which Father Agustín de Campos was building.” [Note 4] (Kino 1913-1922)

|140| ..... As all the Kino and Campos churches were being built of adobe, Kino was overseeing correct cutting of the timbers and assembly of the parts that go into the centering for the construction of the adobe arches.

[Note 4] Crucial here is Kino's statement, “I was ... supervising the cutting and assembling of the timbers for the construction of the arches of the sanctuary ... '" This suggests he was overseeing the operation of assembling the centering for construction of the arches over the sanctuary. Over these arches, if he were referring to the transept, he could have had in mind a dome or vault above the sanctuary proper.

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino 1965-1966

San Xavier Chapel - Facade, Perspective, Isometric Projection

Location of San Xavier Chapel and Magdalena de Kino City Hall

Jorge Olvera

Herbert E. Bolton

The Last Ride

|584| One day near the middle of March, 1711, Kino rode over the familiar trail to Magdalena to dedicate a chapel in honor of his patron saint. It was the very season of the year when first he had threaded that mountain gap just twenty-four years previously. Spring flowers were in bloom and Nature was at her best. Magdalena, too, was in festive garb for the great occasion. But suddenly holiday colors were exchanged for the black of mourning. In the very midst of the dedication ceremony, in which he took a leading part, Kino became desperately ill and soon afterward died.

Herbert E. Bolton

The Last Ride

Chapter 151

With Spirit Undaunted Section

Rim of Christendom:

A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer

Magdalena Church and San Xavier Chapel Drawing

Jorge Olvera

Founder of Pueblo Santa María de Magdalena

Town Planner Kino

|172| How did Father Kino choose the site for the establishment of Mission of Santa María Magdalena? He found this mission in 1687 when he first entered the Pimería Alta, accompanied by his superior, Father Visitor Manuel González. Even that he was in the company |173| of the Father Visitor was in compliance with Ordinance Number 7: “.. . these [discoverers] shall go in pairs so they can render mutual aid to one another." . . .

In the choice of sites for settlement, Ordinance Number 40 recommended: "Very high places shall not be chosen, as they are disturbed by the winds and are difficult of access. Choose intermediate sites, provided with free breezes, especially from the north and south. And if it should be next to a mountain range, it should be seen that this will be on its east side or to the west. If for any particular reason a high place should be built, it should be seen that there is no fog. And if a site should be founded and built on a riverside, see that it is laid out on the east side."

Kino seems to have followed these instructions very closely when he founded Magdalena. He chose the east side of the river and situated Magdalena with the sierras flanking it on the east and west. ... is work as a planner is just beginning to be understood, and thanks in large measure to our research begun during our efforts to locate his venerable remains.

When Kino laid out the settlement of the Mission of Santa María Magdalena, the embryo of the future city, he may not actually have traced the central plaza (what in Roman times would have been the forum). Nevertheless, he had it in mind when he sited the first two and most important buildings of that time: the primitive mission church, begun 1705 (later called the Campos church, because Father Campos was its principal builder), and the chapel of San Francisco Xavier, which he also planned but which Father Campos finished and Kino dedicated in 1711.

These two pillars of the Mission of Santa Maria Magdalena, the first two constructions, were laid out along axis, the cardo [north-south] and decumanus [east-west], that generated the beginning of a settlement destined eventually become a city aligned in terms of Roman planning principles. Looking carefully at the map of Magdalena, one can see that the Chapel of Saint Francis Xavier was built perpendicular to the nave of the Campos church and is oriented exactly north-south, where as the Campos |174| church is orientated exactly east-west. It is known that in addition to his other talents, Father Kino was a trained cartographer (see Burrus 1965). It is more than likely that the man known to have brought an astrolabe with him to the Pimeria Alta used a compass for these operations.

In the positioning of these two buildings lies the generating axis for the growth of the present city of Magdalena and its expansion north‑south along the river and east‑west on either side of it (with most extension to the east where it is not blocked by a steep hill). If the Campos church and the San Xavier chapel had been left in situ and their outlines fully preserved, one would immediately see that the facade of the Campos church and the nave of the chapel faced the later plaza. Also, our later excavations and the unearthing of the foundations of the Campos church and those of the chapel (see Fig. 37, contour map) revealed that the seeds of the first streets and avenues were already contained in the pod of Kino's plan.

One of the first streets to be traced lies in the space created between the facade of the chapel, which faced due south, and the north side of the nave of the Campos church. Immediately parallel to this small and narrow street which ran east west towards the river, there is now Calle Cucurpe, which runs precisely east west from the river towards a second and smaller plaza a block and a quarter from the ancient buildings and a block from the present main plaza. The next main avenue (only a block away from the main plaza) is Calle Obregon. Thanks to Kino, the entire present city of Magdalena is laid out in a chessboard pattern springing from the two axial streets of Roman urban planning: the cardo and the decumanus.

This initial settlement plan made by Kino and constructed by Father Agustin de Campos was not only the starting point for the future city, but it followed certain fortification principles recommended by the Royal Ordinances. One of those ordinances, Number 133, stated: "Arrange the buildings in such a way that the lodgings can enjoy the breezes of the south and the north, and at the same time function as fortresses. Each house will have its own corrals or stock yards.” In the Kino plan for the settlement, the corrals were located behind the Campos church and the chapel, on the slope, was defended somewhat by the sharp drop in terrain towards the river. |175|

Now that we have located the exact place where the Campos church and the Campos priest's house stood, it is further possible to demonstrate how the facades of the Campos church and house, with the lateral facade of the chapel, formed a great defensive wall that in military terms is called a "curtain" (see Fig. 37, contour map). From the contour map one can discern that both the Campos church and the Chapel of San Francisco Xavier were built on the highest part of the site. Behind then was a slope and sharp drop in the terrain to the river. All these elements helped protect the mission. ... If we add the lateral facade of the Saint Francis Xavier chapel, which aligns with these other facades, to these large surfaces and elevations, we have almost a continuous and sturdy barrier or rampart protecting the mission from the east side. It is protected from the west by a sharp drop in the natural terrain and by the river.

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

Mission San Antonio Paduano del Oquitoa

Before Restoration

Kino Churches with Hall Plan Churches and Flat Roofs

Kino's Pimeria Alta Missions

With Establishment Dates

Herbert E. Bolton

The Builder’s Parade

|538| Salvatierra's encouragement did not end with words. He appointed Kino procurator, that is, purveyor, of the Pima missions. The title, it might be said, merely made official a function which the free lance of Dolores had been performing unofficially on all the frontier for nearly twenty years. But it was a recognition of his business ability, and it gave him more authority and more funds to work with. ...

In the middle of January, 1706, Kino escorted Father Domingo to his new mission. At Tubutama they were joined by Minutuli. It was some time since Kino had been at Caborca, but the place had not been abandoned. After Iturmendi departed, Campos and Minutuli kept the sparks of Christianity alive. Messengers had gone before, and elaborate preparations for the visitors had been made by the natives. The three Jesuits were welcomed with all pleasure on the |539| part of more than a thousand Indians. They were waiting with arches and crosses placed along the roads, and had ready "a house in which to live, a church ... , with a good and large hall, storeroom, bakery, oven, kitchen, beginnings of a garden, with maize ready for harvest, a good field of wheat sown and sprouted, and also cattle, sheep and goats, saddle horses, droves of mares, etc."

The reoccupation of Caborca was the beginning of a missionary revival in the Pimería, carried through by these sons of Italy. As procurator, Kino now directed a vigorous program of building, both in the Altar Valley and to the north of Cocóspora. Of his work he left us a precious record. He started the new enterprise on Ash Wednesday. Having given ashes and confessed communicants at Dolores, he set out to do the same elsewhere. With him he took servants and guasinques, or native builders, for he had six churches to build or repair. And there were orchards and gardens to plant.

From Cocóspora Kino went down to Magdalena and inspected the “squaring of the timbers for the building and the arches of the sanctuary of the very good church" which Father Campos had under way.

At Búsanic and in each of the other pueblos as he descended the river he rendered the same services-gave ashes, said Mass, preached, heard confessions, baptized, and solemnized marriages. While he gave spiritual ministry, he directed his builders. His expedition was a typical combination of the functions which every frontier Jesuit had to perform. "As they already had in San Ambrosio del Búsanic a good supply of adobes and some timbers, we raised the walls of a good, spacious church." From dawn to dark, hammer, saw, and trowel beat a cheerful tattoo, and as the hours lengthened the adobe walls rose higher. "We wrought and placed in the doors of the church, and of the sacristy and of the baptistry, the entablatures of very good timbers, and arranged that they should continue on the building of the church of San Ambrosio del Búsanic, and on the neighboring one of Santa Gertrudis del Saric, since for both there were crops of maize, and cattle, sheep, and goats, and whatever else was necessary." Only missionaries were lacking.

At Tubutama Kino was again welcomed by Minutuli "with his accustomed great charity." For three days the guasinques worked on the church, "laying the foundations of a good sacristy and of the baptistry, and of a good, spacious hall, as well as raising the walls of the church, and especially of the sacristy, and cutting and working the timbers, brackets, beams, and arches or lintels, etc. Also we looked after the very good garden of Castilian fruit trees, vines for wine for |541| masses, and all kinds of garden stuff." Rare data for the history of the spread of European culture.

Kino continued to Caborca, "where the very courteous children “gave him an affectionate welcome. From this I infer that Crescoli was not there. Was he too a bird of passage in the Pimería? Over these matters Father Eusebio usually spread the veil of charity. While he gave ashes and heard confessions, the guasinques worked on the Caborca church, "laying the foundations of its buildings and raising their walls and those of the sanctuary, and on the church of San Diego del Pitiqui." Having received a letter from Father Picolo, saying that he would soon come again to the Pimería, Kino hurried back to Dolores.

The parade of the builders was not over. After the celebration of Holy Week at Dolores early in April, which was attended by four chiefs from San Xavier del Bac, Kino went northward on a pastoral and building tour similar to the one he had just made to the Altar Valley. He took with him the captain of Dolores, the governor of Remedios, a temastian or native catechist, three guasinques, and three other servants. His cowboys drove a herd of cattle for San Lazaro. Of course he had the necessary pack train with the outfit.

At Remedios, Cocóspera, San Lazaro, and Santa María, Kino heard confessions, instructed catechumens, preached, baptized, and solemnized marriages. Meanwhile the masons and carpenters were performing their more material tasks. At Santa Maria, Kino tells us, "we laid the foundations of a good, spacious hall and of two good lodges, and we began to raise their walls, for already some little storerooms had been made, and a little hall; and the foundations were also already made of a good and large church, with its transept, for which the guasinques cut twenty pine beams and forty oak brackets, and other wall timbers for the house. And an order was left that they should continue making adobes and building and finishing the spacious hall, that it might serve as a little church in which to say Mass with decency while the great church was being built." These are precious details regarding the interesting old pueblo of Santa María, now Santa Cruz, which still stands on the same site, San Lazaro was the scene of like activity. There, says Kino, "we began another |542| little hall with two lodges. It is a post very suitable for a good pueblo and for a very good ranch/ and, indeed, some corrals had already been made. We left at that post twenty-three beef cattle, with their cowboys."

Still the parade was not over. In May Kino and his guasinques went again to Tubutama and Caborca on a missionary and building tour. ...

In the summer of 1706 news arrived that more workers were coming from Europe, and Picolo seized the opportunity. Pima Land must get her share. For data on which to base a new request he turned of course to Kino. To whom else could he turn? |543|

More reports! Kino might well have groaned. Instead he complied with the enthusiasm of renewed hopes. There should be no slip on his account. The required document was drawn up promptly and dispatched by special messenger to Picolo at Guaymas.

The manuscript included a long account of all the good sites in the Pimería, a map of the nine missions already under Kino, Campos, and Minutuli, and a request for at least five new missionaries for fifteen new pueblos. The nine active missions, of course, were Dolores, Remedios, Cocóspora (Kino), San Ignacio, Magdalena, Imuris (Campos), Tubutama, Santa Teresa, and Oquitoa (Minutuli). For the five new fathers Kino proposed the following pueblos: 1. Caborca, Pitquin and San Valentin (a few leagues west of Caborca). 2. Santa Maria, San Lazaro, and San Luis Bacoancos. 3. Búsanic, Saric, and Aquímuri. 4. San Xavier del Bac, San Agustin, and Santa Rosalla of the Sobaipuris. 5. Santa Ana del Quiburi, San Joachin (Huachuca), and Santa Cruz, "where lives the famous Captain Coro." The old chief had returned to the San Pedro, once more to challenge the Apaches.

For these missions the groundwork had already been laid. "For in all these posts or pueblos named above there are very good beginnings of Christianity; houses in which to live, churches in which to say Mass, fields and crops of wheat and maize, and the cattle, sheep, goats, and horses which for years the natives have been tending with all fidelity for the fathers whom they ask and hope to receive." This report is a good summary of the status of missionary work in the Pimería in the middle of 1706. Picolo was pleased with it and hurried it to Salvatierra, who sped it to Rome.

Herbert E. Bolton

The Builder’s Parade

Chapter 141

Sons of Italy Section

Rim of Christendom:

A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer

Kino's Flat Roofed Hall Floor Plan Church Examples

San Antonio Paduano del Oquitoa By Architectural Review

Santa María de Bugota By Document Review

Mission San Antonio Paduano del Oquitoa

Existing Church Like Kino's First Churches With A Flat Roofed Hall Floor Plan

Mission San Antonio Paduano del Oquitoa Resembles Kino Church

|130| There are some early mission structures still standing, both in Sonora and New Mexico, that offers clues as to the appearance of Father Kino’s church in Bugota. ... I think most of Kino’s churches were essentially the “hallenkirche,” or hall type ...

A Pimeria Alta church still standing and in use that may resemble a primitive Kino church is that at Oquitoa. It was under construction by 1730, nineteen years after Kino's death (Schuetz Miller and Fontana 1996: 70 71). Kino had begun a church here as early as 1705, but it was apparently never built.

The interior of the Oquitoa church, with its nave and sanctuary; covered by vigas resting on carved wooden corbels, would be very much like Kino's own mission churches. Even its exterior, with the exception of the Franciscan added facade, is probably a good resemblance. Inside, the floor plan follows the mudejar tradition undoubtedly brought into Sonora by Kino and other Jesuits. There is an elevated presbytery with respect to the nave, an outstanding mudejar trait of lower Andalucia, as we have seen. The church, like those at Franciscan Turnacacori and San Ignacio, may once have been provided with a transverse clerestory window in the rise for lighting and defensive purposes. Transverse clerestory windows, including those in 17th century built Guadalupe in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, and at 19th century Socorro, Texas, eliminated the need to have windows in the walls of the nave, an important consideration where Apaches or other potential enemies might attack. After the danger passed, many transverse clerestory windows were later walled in.

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

Kino's Flat Roofed Hall Floor Plan Churches

Are Similar to Existing Churches of New Mexico

San Miguel, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Figure. 25)

Kino's Santa María de Bugata, Sonora 1709 (Figure 26)

Chapel, Chimayo, New Mexico (Figure. 27)

Drawings by Jorge Olvera

Santa María de Bugota By Document Review

Kino's Hall Floor Plan Churches Are Similar to Existing New Mexico Churches

Jorge Olvera

Finding Father Kino:

The Discovery of the Remains of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J. 1965-1966

Building at Santa María de Bugata